Winter Nomads of ‘Out There’

Lightsey Darst has been a regular at the Walker's annual festival of global, contemporary performing arts and offers a dispatch from the scene, observing that when you're Out There -- it's the audience, not the shows that really make the festival.

IF THE NEW YEAR’S FESTIVITIES ARE OVER, THE CHAMPAGNE IS FLAT and the chill has set in, then it must be time for Out There, the Walker Art Center’s twenty-three-year old January festival of the emerging, the risky, and bizarre in performance. The name’s always amused me. I picture a committee spinning their pencils, debating the merits of Weeks of Wackiness and Weird!! before settling on Out There, which one of them probably overheard a beige-clad matron mutter as she left the theater one evening: “Well, that was a bit out there, wasn’t it?”

But, on second thought, this is the perfect name. Set aside the Minnesotan way it at once frames, apologizes for, and defends the work; set aside the probable cackling of the artists when they find out how they will be billed to the good people of the North. This name tells a story: One winter evening, a group of intrepid people bundled up, left their warm hearths, and set out in search of a vague hinterland, a place someone once described, waving an arm, as Out There.

Because that’s what makes this a festival: the audience, not the performances.

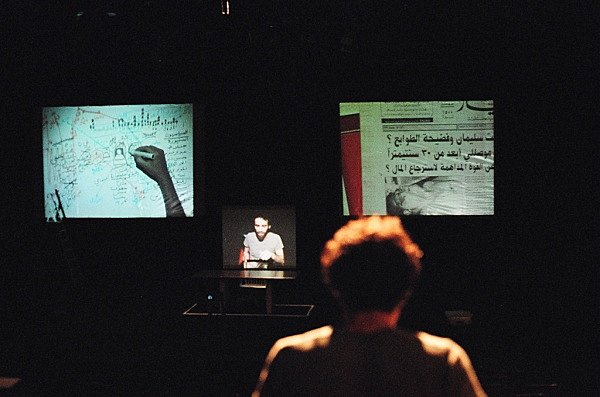

Not that we’re always bundled up. The first weekend, it was actually warm enough for fashion — a strange irony, given that we’d come to see a party of naked women in Young Jean Lee’s Untitled Feminist Show. Mostly, though, when we head out to see something in Out There, we are freezing; after the performance we toddle or drift down the street to Rye or the Lowry to warm up, or maybe over to La Belle Vie, where a dangerous martini called The Night of the Hunter wears our memory of Rabih Mroué’s quiet Looking for a Missing Employee down to a faint nub. Or if not a nub, a sparrow-scatter of details… One of these days, I’m going to write a piece in which I compare what people think on the night of the performance with what they remember a year later, because I’m curious how that works. For me, as usual when I relax my professional attention, I remember a lot of context: the woman reading An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter in the queue on the stairs, lost in her own world and gently smiling while everyone around her strains their antennae for signs of Out There-ness; the young woman brilliantly dressed (arrowy earrings), constantly looking around for the date who never shows; artists one knows looking cold or sleepy or new year-ish (Monica Thomas with streaks of purple in her hair).

I wrote down a conversation I overheard the second weekend: “How did you feel about the naked ladies?” one man boomingly asked another. The response was inaudible. “I thought it was awful! Naïve and earnest and boring and I’ve seen it and what’s feminist about it? I’ve seen it for thirty years.” Yes, there is a sense of endurance about Out There, a distinct grey tinge to the audience, especially after the naked ladies go home and the weather turns cold. Some of these people have soldiered through years of Out There in search of… something, and it doesn’t seem they find it much.

Perhaps it’s this vague void that the Walker attempts to fill with its voluminous program notes, talk-backs, thinks and drinks, etc. Nice try, everyone, but the sheer amount of this accompanying stuff only gives the impression that what’s on stage is somehow not enough, that it’s merely a surface or skin, or (dare I say it) that what’s on stage is entertainment, and entertainment is not what the pilgrims have come for.

______________________________________________________

There is a sense of endurance about Out There, a distinct grey tinge to the audience, especially after the naked ladies go home and the weather turns cold. Some of these people have soldiered through years of Out There in search of… something, and it doesn’t seem they find it much.

______________________________________________________

It’s true that talk-backs and program notes give context, answer questions, explain themes, etc. Everything The New York Times complained about in Young Jean Lee’s Untitled Feminist Show (basically, that the show is too slick and enjoyable, too opaque, lacking in potable statement on its apparent theme) was answered in that talk-back — which I inadvertently heard, having been decoyed to the balcony bar by free drinks that only I was enjoying, guiltily scarfing down white wine as everyone else asked sincere questions and listened to sincere answers. Frankly, I couldn’t drink the wine fast enough, because I actually liked Untitled Feminist Show, and I wanted to get out of there before the production utterly disappeared for me under the weight of explanation; I wanted to leave with my dreams intact.

Perhaps that’s a childish perspective, especially given that I am a professional explainer myself. But no, I don’t really believe that. There must be some value in the performance object as is, in its surface, however slick or uncommunicative. I would never say that talk-backs have no value; I certainly wouldn’t greet their announcement with a raspberry, as one patron did. But demystification comes at a cost: mystery.

IS OUT THERE REALLY OUT THERE? Such gestures at breach or enchantment have become routine. I have never before really been in a theater where naked women have come down the aisles, breathing heavily, and yet I have. Rabih Mroué’s Looking for a Missing Employee (which also opens with breath) features one of those is-it-over endings, in which applause peters out into blankness, no bow is taken, and viewers must simply decide to leave. It’s destabilizing in the moment, but when you’ve done it before, more on the order of being scanned at the airport. In fact, at times, in all of these clever, innovative, entertaining shows it suddenly comes across what an ordeal it is just to sit still and pay attention (and at the end of the day, too).

And what rewards that attention at Out There isn’t the sort of broad catharsis that races across the audience like a tidal wave. Instead, it’s the personal break-point. So far, this year that’s come mostly through comedy. chelfitsch Theater Company’s Hot Pepper, Air Conditioner, and the Farewell Speech features absurd conversations among office workers — repetitive, uncommunicative, and punctuated with strange gestures. Watching this heightened version of the purgatory of much modern work (i.e., much of our lives), people lose it at various moments, unpredictably. You laugh and find yourself alone, your laugh sharp, a little hysterical, like a cry.

Later, after the show, you compose yourself, get up, wrap yourself in winter things, and file out. Your fellow theater-goers have similarly shut faces; it’s impossible to say when or whether they felt something, or if they did, what it was. They are diligent seekers, though, and they will likely return next week. For now, quietly, the nomads of January sift out into the snow.

______________________________________________________

Related information and links:

This year’s performances for Out There 2012: Global Visionaries began January 5 and will close January 28 at the Walker Art Center. This weekend’s show, Mario Pensotti’s El Pasado es un Animal Grotesco (The Past Is a Grotesque Animal) will be January 26 at 8 p.m. in the McGuire Theater. Walker Magazine editor, Julie Caniglia, has an interesting related essay on the center’s website as well: “Out There 2012: Present.Tense.Theater”

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl was recently published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship.