Game On

Camille LeFevre reviews Sarah Michelson's recent world premiere at the Walker, "tournamento," a game-in-dance performed for audiences over several days — with distinct rules, systems, codes, plays, penalties, and color commentary — according to its own inner (if often unfathomable) logic.

Sarah Michelson likes to play with her audiences — at least with her audiences in Minneapolis, where she’s premiered three works commissioned by the Walker Art Center in the last decade. Whether challenging our expectations, spiritual beliefs, sense of appropriateness, physical comfort, or traditional notions of theatrical presentation, the British-born, New York-based choreographer likes a bit of cat and mouse, with all of the thrill if not the kill. Her game is really more catch and release.

Ten years ago, Michelson’s Daylight (for Minneapolis) exhilarated and/or infuriated audience members with a game of hide and seek. In the Walker’s brand-spanking new McGuire Theater, the seats were unoccupied. Most of the audience sat in three seating sections facing up stage, where repeating phrases of luscious choreography took place. Otherwise, attendees were relegated to the front row of the center balcony, where they could observe dancers around the live band, or moving along the side balconies, or between the theater seats, or performing on a narrow strip behind the stage seating—as well as the group on stage.

In 2011, Michelson premiered Devotion, a work created in collaboration with playwright/director Richard Maxwell; that time, it was a game of dare and daring. Archetypal stories from Christianity formed the basis of the text, while the dancers’ sweated through their tops, shorts, and swimwear during rigorous sequences of repeating patterns, steps, leaps, and runs. Meanwhile, the temperature inside the theater was exceedingly warm—and it only got hotter as the performance went on. Were we meant to feel the fires of devotion, just the dancers were? And what about the painfully thin girl with her fierce, mechanical, exhaustive movements? What sort of self-denial or punishment did she represent, which was painful to watch.

Now, we have Michelson’s tournamento. Rather than toy with the audience, however, Michelson’s recent premiere at the Walker literally presented us with a game, a tournament, which—guessing from the conclusion of Thursday night’s performance—continued for several afternoons and evenings. Dance as a sporting event isn’t a new idea: In the past, I’ve heard audience members who are also sports enthusiasts speculate on the value of pre-, during and post-show commentary (which would apparently be more snappy and direct than the talkbacks and audience-performers discussions often held in the theater). Numerous choreographers have used sports or games as inspiration for their choreography. And dance competitions—replete with judges, costumes, teams and scores—are a regular part of many dancers’ lives.

But what Michelson’s created with tournamento is wholly different. Think bingo meets capture the flag, with qualifying heats and a dose of Olympic competition, the maneuvering of chess games, muted broadcasts of tennis matches, and grid-like orientation of an early computer game. Like any other sport, tournamento has its own rules, systems, codes, plays, and penalties. As the dancers yell out numbers and letters, or call out to be captured and receive refereed responses, it all sounds like gibberish, but gibberish with its own inner, unfathomable logic.

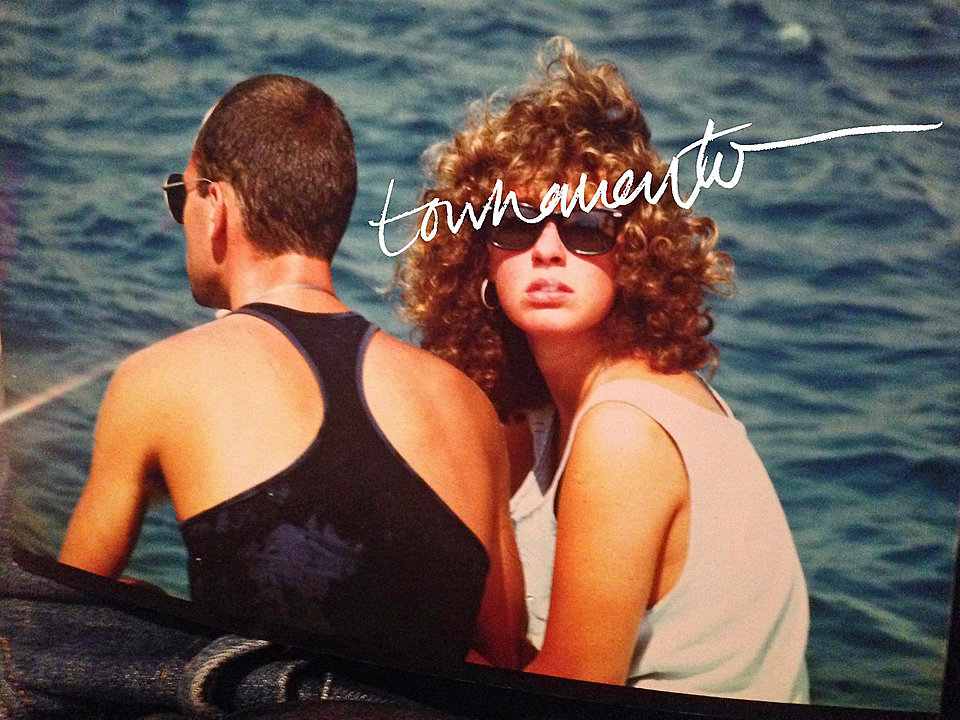

Like all sports or teams, this tournament also has a brand: a photo of Michelson’s face and lustrous head of curly hair, circa 1984, which regularly appears on the many screens above the stage. Her tournament also has an insignia or logo (also part of its brand): a drawn outline of Michelson’s hair, sans her face, which also appears onscreen from time to time and is projected onto the playing floor.

tournamento has three judges, dressed in black, who bark numbers and letters in response to the performers; these judges hand out scores and accept or deny appeals. Various referees, ball girls (sans the balls), and support personnel mill around with determined efficiency, sometimes breaking into movement phrases of their own. Players and judges flip the numbers on scoreboards placed on the floor, on the walls, on tables. A man—wearing a t-shirt with the Michelson hair logo X-ed out with tape—stands in the audience with another laptop, operating still another scoreboard.

Michelson—operating three laptops and a soundboard—is the commentator. She offers some play-by-play in the smooth, quiet voice we associate with sports commentators, particularly during tennis matches. But she also screech-barks, “Let’s play!” into the microphone; it’s more annoying than menacing. She frequently alters the looped yacht-rock and disco selections—musical interludes reminiscent of sporting events—from tinny analog to ear-splitting stereo.

Entering the tournament are four primary players: Rachel Berman, or Red, from Hawaii; Jennifer Lafferty, Blue, representing Southern California; John Hoobyar, Green, for Oregon (they are, actually, all from the states they represent… except we don’t know about Nicole Mannarino, wearing Yellow for Ohio, whose bio isn’t included in the program). Endurance, repetition, and athleticism are on display; each player performs his or her own movement phases with a singular virtuosity.

Over and over again, Green for Oregon leaps, jumps, kicks, spins, or does splits in the air—landing on the balls of his feet, perhaps quivering with exertion but never losing focus. Initially, Red for Hawaii is on the floor, lifting her legs, shifting her feet, lunging, and turning her torso with exquisite concentration; later she’s up, long and lean, striking lengthy balletic poses requiring perfect balance. Blue for Southern California hugs one leg up to her chest for one-legged balances, hunches over and slouches across the floor, slide planks, kicks up one foot and hits the opposite thigh with it. Yellow for Ohio is boisterous; she sucks her stomach in and out, flexes her back, hugs her arms to her side, and moves her feet in and out with mechanical precision.

All the while, the players are yelling out letters and numbers, with the referees and judges responding. The players’ “seconds” are swaying back and forth in the aisles, also shouting. A judge gets up to watch a particular player and offers a score. A player comes to the microphone and asks the judges to reconsider a move and its score. Appeals are heard, denied, accepted.

Apparently, it’s halftime. As the judges discuss, the players retreat and out comes a little girl doing cartwheels on the floor logo—in a green leotard, then blue, then red, then yellow. Michelson announces a new round. Michelson agrees or disagrees with a judge’s decision. The screens overhead show scribbled plays (as in football), sketches of the players’ faces, Michelson circa 1984, the Michelson hair logo, footage from past games.

It’s cacophony. Impenetrable. Enigmatic. And yet, overflowing with action, sound, movement, gesture, according to a secret system only those participating are privy to. The game has its compelling moments. Green for Ohio collapses on the floor, weeping. Yellow for Ohio gets more competitive. Blue for Southern California stays fiercely cool. The movement is wondrous to behold.

Still, tournamento is a game without consequences, without a backstory, seemingly without a reason and without an end, and with no implication for the audience, without whom the games could certainly continue. Why have we been invited to watch? What are we expected to take away? Perhaps tournamento simply is for the sake of itself, and thus an artifact to be puzzled over long after its resolution.

Noted performance information:

Sarah Michelson’s tournamento premiered at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis with performances September 24 through 27, 2015.

Camille LeFevre is a long-time dance writer in the Twin Cities and the editor of The Line, an online publication about the creative economy of the Twin Cities.