Why Is Cindy Sherman Making Faces?

Lightsey Darst says the Cindy Sherman show is one of the most important bodies of feminist art today, but not for any of the reasons cited on the wall in didactics accompanying the artist's retrospective (at the Walker through Feb. 17).

THE DIDACTICS ACCOMPANYING THE Cindy Sherman retrospective (at the Walker through February 17) are truly didactic. They tell the reader-viewer what the work is and does, often by adjective—groundbreaking, important, celebrated, monumental. They are at once unnecessary—does anyone with even minimal familiarity with recent American life really need to be told what this work does?—and gross: They reduce Sherman’s kaleidoscopic effect to unitary statement.

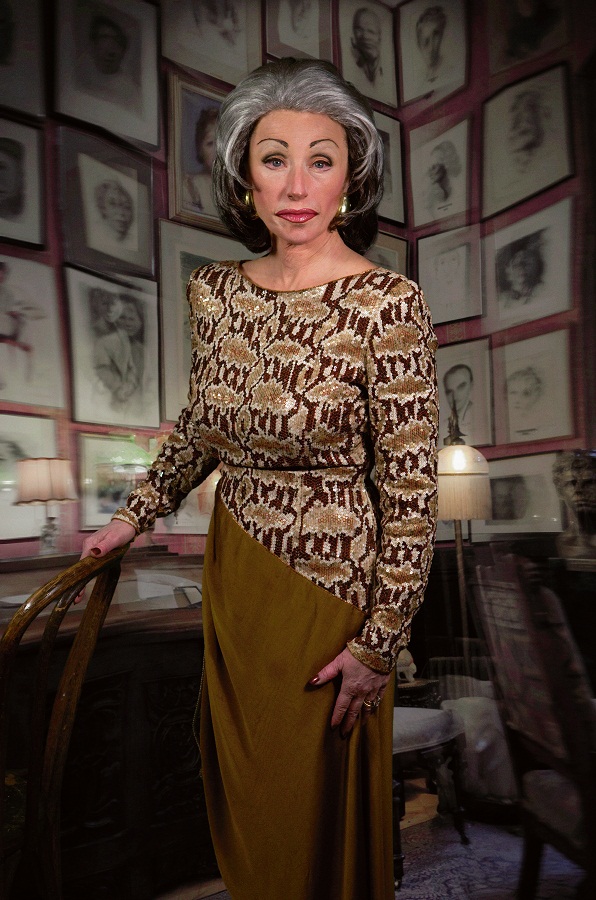

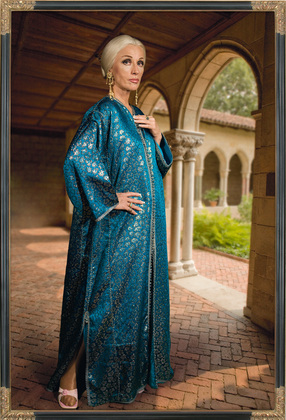

A case in point: the didactics call the 2008 “society portraits” (all Sherman’s work is untitled, but her series have informal names), magisterial dames in faintly surreal backgrounds, “tragic and vulgar,” and absurdly report “these well-heeled divas presaged the financial collapse of 2008.” Of course they did not presage anything, but I’m more concerned with “tragic and vulgar,” with the superior stance the didactic-writer takes towards these ladies—a stance I don’t think Sherman shares. (How could she? She’s inside them.) Tragic, all right, everyone is, but what is vulgar about these valiantly achieved selves? Steel magnolia, white-gloved philanthropist, lovelorn heiress and former beauty, sultana, and yes wife to a wealthy man—who thinks these are easy identities to build and maintain, as these women maintain them, into a fifth decade and more? Look at the woman I think of as the sultana (Untitled #466), with her white chignon, her regally blue caftan; look at her disciplined yet calligraphically graceful line, her perfectly calibrated smile, part sweetness and all command. This is not a person to be trifled with. Contempt is only possible from a distance—and it reveals more about the contemptuous than it does about this artfully armored self.

That is what I mean by Sherman’s “kaleidoscopic effect”—her images reveal and conceal in alternating and shifting layers. I’m thinking of the constantly changing password that protects a diamond in a heist film: the depth we plumb to keeps changing, but the answer returned is always no.

Let me leave that problematic assertion for the moment and follow up another point. Why are the didactics accompanying Sherman’s images so insistent? I suspect it’s because they are trying to justify the gathering of these works and explain what these works do all together. And just what do we encounter in these rooms? To me, it seems we meet one of the most successful bodies of feminist artwork. But does that really require comment? Actually, perhaps my word choice does—bodies. . .

But let’s back up from these quandaries. Originally, as I considered this piece, I thought I might describe a few images, imaginatively enter them, spin out stories from them. But when I tried that, I found it an unrewarding exercise. Let me demonstrate.

Untitled #3 (one of the “film stills”): a housewife—apron, bob, Nike Zeus missile launcher bra under a cheap sleeveless blouse—half-turns from her sink. One hand holds her belly, the other props her on the edge of the sink; her elbow hyperextends dramatically and her bare shoulder almost caresses her cheek. She looks fixedly out of the corner of her Cleo eyes at someone; or maybe she’s thinking, looking sidelong as people do when a thought is almost beyond reach. Her next move might be to dig a knife from the dish drainer and give her husband what he’s been asking for, or maybe she’s arrived at the instant in which she’ll hang for the next fifty years. Or both. The wonder is that these possibilities don’t seem mutually exclusive, or definitive when you consider Sherman’s image closely: Maybe she’s playing at both, seducing someone with mock-psycho-wifeliness.

_____________________________________________________

When I talk about Sherman’s success, her achievement, this is what I mean: She masters the visual that ordinarily masters us. Some women work hard to find a look, a mode in which, despite their “defects,” they become alluring, but Sherman nixes that whole game.

_____________________________________________________

Portraits are often praised for being revealing; Sherman’s seem at first to be so, but turn out to reveal mostly the visual trappings of certain moments of self-presentation. I apologize for the gobbledygook. The images don’t require it: They wear their enigma boldly.

I passed a woman in the Cindy Sherman exhibition carrying a bag emblazoned with an image of Frida Kahlo. Despite the shared fixation on the self-portrait, it strikes me there could hardly be an artist with a more different effect. Kahlo’s work comes across as expressive, poetic, dreamy, personal; her self becomes lovely in the showing, a beautiful woman and a sex symbol despite the moustache and unibrow (which are tellingly effaced in some images made of her—including this “Sexy Surrealist” costume). Sherman’s work, on the other hand, is formal: she registers every detail of a porn snap, for example, and replicates it with a fake vagina cockeyed between a pair of jointed wooden legs, grotesque falsies, and a face coolly regarding us from a bondage mask (Untitled #264). The effect is inviting but distinctly not fuckable.

Pardon the word: I think it’s necessary, because that’s what’s at issue here, isn’t it? When I talk about Sherman’s success, her achievement, this is what I mean: She masters the visual that ordinarily masters us. Some women work hard to find a look, a mode in which, despite their “defects,” they become alluring, but Sherman nixes that whole game. To age, exposure, class, attractiveness—the little everything of the visible female—Sherman provides a brilliantly multifaceted refusal.(A sidenote: one aspect Sherman doesn’t change is her perceived race. In a few images from 2000-2002 she approaches mixed; otherwise, she stays white.)

In this light, I wonder at the Walker’s two “Dress up like Cindy!” events—the “Pick Your Persona” ball and the “I Heart Cindy” evening. Most people dress up to become more attractive; that’s why Halloween costumes for women are almost always sexy. I’m sure these events will be great fun, but I suspect they’ll also arrive at a feeling almost opposite to that of Sherman’s art.

All this takes me back to the effect of the exhibition. It’s undoubtedly an achievement, and stunning, but as such, seeing it is something like seeing a person on top of a mountain: the only aid provided is the proof that the mountain can be scaled. But this metaphor partakes of the wrong ideals. Rather, what you see is a woman standing in a valley, mysteriously looking as though she’s scaled a peak.

_____________________________________________________

Noted exhibition details:

Cindy Sherman, a retrospective exhibition on loan from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, will be on view at the Walker Art Center through February 17. Here find MoMA’s exhibition website for Cindy Sherman. See also: https://www.artsy.net/artist/cindy-sherman

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl was recently published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She writes a weekly column on dance for mnartists.org.