What’s the Meaning of All This?

Considering the art of interpretation by way of three shows at Pete Driessen's TuckUnder space, where the art stands alone - no labels, no explanations. But when is such silence about artwork intellectual largesse, and when is it cover for timidity?

IN THE JULY ISSUE OF HARPER’S MAGAZINE, professor Mark Edmundson argues that contemporary American poets have lost the emotional verve required to craft strong declarative verse that was so well-stocked in the works of earlier poets such as Whitman or Lowell. Content with leaving a work’s meaning obscure, many poets today shirk the potential authority which a voice with an audience has the privilege to establish. To be clear: establishing intention is not the same as dictating all possible meanings. But rather than owning their creative purpose with lucid allusions and a clear conjunction of voice and style, today, Edmundson argues, many poets defer to their readers, rarely daring to decisively claim any ground lest they be branded politically incorrect or culturally insensitive. Edmundson writes: “How dare a white female poet say, ‘we’ and so presume to speak for her black and brown contemporaries.” But his argument extends beyond race, and attempts to reveal contemporary writers’ broader reluctance to assert to authority. The problem, he argues, is that the timid poet “gives critics far too much room to determine poetic meaning.”

Those who wish to understand the state of contemporary visual art would be well served to apply Edmundson’s line of reasoning there, too. Fearing any moral or public blowback, many artists today are similarly inclined to tie oblique ideas to the knotted strings of theory and conceptual art. Contemporary debate over meaning in works of art jostles between arguments for greater authorial and critics’ control of the message, on the hand, and unhindered interpretive freedom for audiences, on the other. Some contemporary artists and critics hesitate to cede any such authority to the masses, while others argue for egalitarian, open modes for artworks’ creation and criticism.

An institution displaying provocative and obscure works can offer such guidance to the viewer through labels, artists’ statements, catalogs, and other supporting materials.The curator who chooses not to utilize such tools to help viewers navigate their experience creates an environment for showing art where the onus of interpretation falls entirely on the viewer —a potentially dizzying scenario.

Pete Driessen, artist, founder and lead curator of TuckUnder Projects, a kitschy home/gallery hybrid in Minneapolis’ Fulton neighborhood, takes a third path: he chooses not to have any didactic material, instead offering himself as an educational guide. Without traditional open hours, visitors make appointments to visit, and Driessen walks them through each of his exhibition spaces: the eponymous tuck-under garage, a charming back yard, and the “Leaky Sink Gallery” (a bathroom with a broken faucet).

The garage’s current exhibition, Emanations by Holly Streekstra, is “an especially conceptual series,” he tells me, “which is why I broke my own rule and printed an artist statement.” Driessen usually eschews didactics for fear of dictating to viewers how they should see the art. “It’s more contemporary, I think. Didactics can de-socialize a space. I want everyone to talk to each other. I want the art to be open-ended and to allow viewers to distribute their own ideas.” I appreciate and admire Driessen’s desire to provide viewers the necessary space to generate their own meanings from the work. This approach, however, which denies much by way of contextual resources, unwittingly creates an even greater interpretive challenge for the viewer who is tasked with attempting to parse already-oblique installations.

There’s something sweet and earnest about Pete Driessen and his home gallery. It’s a young art program, and one that reflects the modesty of its quiet urban neighborhood. All proceeds benefit the space, and all sales go directly to the artist. His intentions are laudable, even if the execution of the venue’s exhibitions may still be finding stable ground.

Holly Streekstra designed her exhibition specifically for the TuckUnder garage. According to her statement, she wished to associate “the reality of experience with the semi-subterranean nature of the tuck under garage,” in order to explore the “trans-communication between mortal and ethereal.” Her multi-sensory installation consists of black shelves—some empty, others supporting objects sourced from estate sales, including urns leaking mold, old liquor bottles, and a dusty, gooey flower. Tufts of cotton hang nearby—almost like clouds but constructed with mysterious substances—twirling at an uncannily even pace and rhythm. A fan, tucked away above the installation, quietly generates the movement. Streekstra has adorned the urn with synthetic fluids, and the flower is actually plastic, covered with powdered fabric and drops of glue. Strange, indistinct noises fill the room, and something faint tempts your nose — blooming flowers and dead petals. A radio emits s-wave bursts recorded from the surface of Jupiter, and the smell comes from another urn, situated in an upper corner and filled with a funereal concoction of rose water perfume and stargazer lily paraffin wax. Streekstra uses these and other theatrical devices –curtains, lights and mirrors — to perform the effects of spiritual incantations and ectoplasmic reactions. Emanations provides the pleasure of experiencing something impossible together with the satisfaction of knowing the magician’s secret.

______________________________________________________

Low tech/high joy’s work is delightful, utopian. This is what TuckUnder does beautifully: fostering an authentic, straightforward use of space for projects tailor made with an invitation to engage and play.

______________________________________________________

Marlaine Cox and Karen Kasel, working as the low tech/high joy collaborative, sprinkled the backyard with tools for wonder. During their six-month residency with TuckUnder, the duo hosted welding classes and developed another project, the Sunflower Revolution, for which they’ve distributed homemade, hand sewn bags full of seeds from their own gardens. In the TuckUnder yard, they’ve planted several bright orange, rudimentary telescopes, all handmade from recycled materials, intended to pull the viewer in to see what might otherwise go overlooked: a peculiar pile of polished white rocks; a mouse’s front door; a leash dangling from a tree. “The people who lived here before left that behind,” Driessen explains. “We’re guessing it used to be their pet’s.” TuckUnder shines in these kinds of quirks. Cox and Kasel’s project is precisely as it seems. Intentions are clear and direct, the point is evident: take a moment, kneel down, look up, look again, and again. Sprinkle some life around you. Low tech/high joy’s work is delightful, utopian. This is what TuckUnder does beautifully: fostering an authentic, straightforward use of space for projects tailor made with an invitation to engage and play.

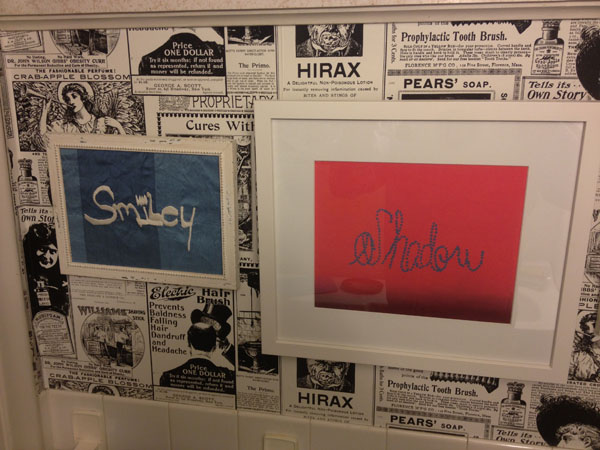

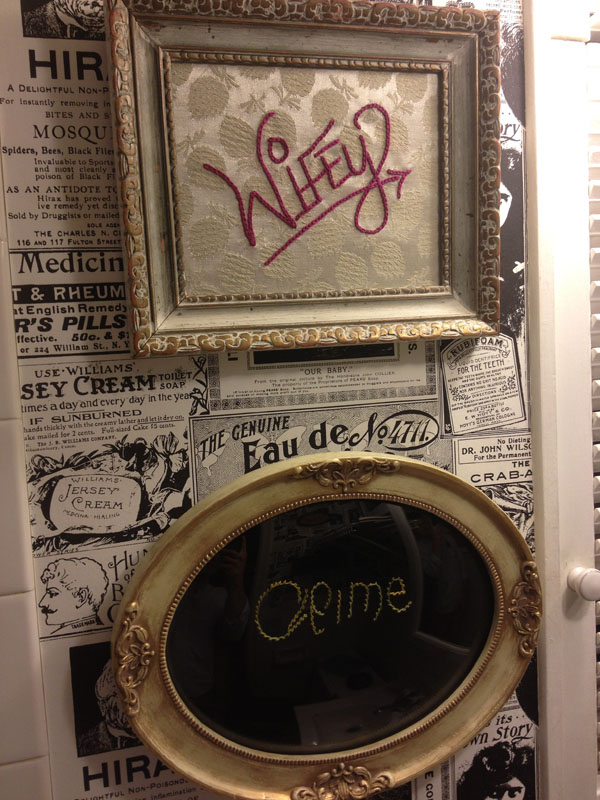

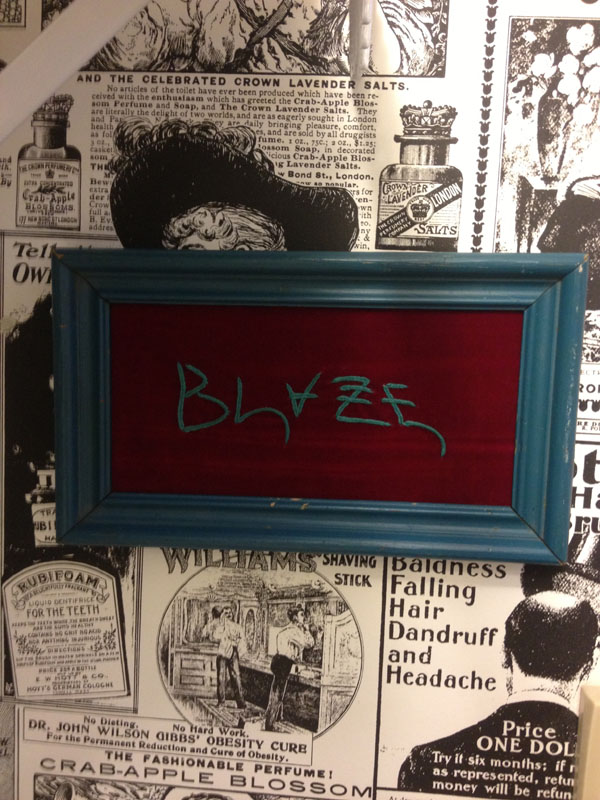

In the Leaky Sink Gallery, Jenny Jenkins uses antique frames for her printed and embroidered copies of 10 graffiti tags she’s spotted across Minneapolis. Jenkins is a talented embroiderer, using the original handstyles of the tags to decorate fine fabrics with the words “Stoner” and “Crime” or “Smiley.” Three of Jenkins’ copies are screen prints, a medium common to DIY practice and emblematic of the movement’s defiance of established forms of art-making. Clever as it is to juxtapose the raw nature of graffiti with the more delicate mediums of silk screening and embroiderery, Jenny Jenkins’ Driftwool is both a well-adorned visual pun and an unfortunate sort of appropriation.

The debate over the state of graffiti as either art or vandalism often overlooks the basic nature of the form as a free and public form of expression. Sociologist Gregory J. Snyder argues that graffiti is in fact both art and vandalism: though emotionally charged and virtuosic, the marks are still officially property damage. Communicating to the masses on streets we all use and on buildings we all see, graffiti writers, Synder writes, want “to get fame and respect for their deeds, and therefore they write in the places where their work is more likely to be seen by their intended demographic.”

In the Leaky Sink Galley, Jenkins has magnified the potency of anonymity by further removing the original artists from their art. Jenkins performs with a power she’s privileged to wield by commandeering the work of these nameless writers and positioning them outside their intended space. In the absence of any explanation to guide a viewer towards a more nuanced understanding of the symbolism at play in this work, one can only speculate whether Driftwool functions with insightful irony, pairing different methods of mark-making across history, or if her copying is the evidence of oblivious privilege. With the absence of a bold statement, or indeed any statement at all, this provocative but ill-defined space designed by Driessen and Jenkins ultimately challenges the viewer to engage in a difficult interpretive environment.

Nina Simon, author of The Participatory Museum and executive director of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, offers a counterpoint to the unstructured art exhibition. She argues that the successful project needs to offer scaffolding on which viewers may choose to build. For example, a desk in the corner with a typewriter and a sign that says “Write a poem” offers very little scaffolding. Visitors, Simon believes, need something that specifically incites response, something which offers a route for communication. Such scaffolding shouldn’t be dictatorial, or even prescriptive—it need only to provide a few directed paths from which to choose. Without such scaffolding in the form of contextual material, art on view becomes mired in a space of limitless interpretive possibility. Some might feel empowered in such an open-ended environment, but others could just as easily feel lost or excluded. In this free-for-all mode of exhibition, I guess that’s up for each individual viewer to decide.

______________________________________________________

Noted exhibition details and related event information:

The closing party for two of the noted shows, Driftwool by Jenny Jenkins and Emanations by Holly Streekstra, will be Thursday, July 25 from 7 pm to 9 pm. If you can’t make the closing, you can catch a few final days of the month-long exhibition period for these shows with unstructured viewing hours or by appointment, Wednesday through Sunday, July 28. The low tech/high joy collaborative residency will continue through the fall. Find more information: https://www.facebook.com/lowtech.highjoy

TuckUnder is located at 5120 York Avenue South, Minneapolis, Minn., 55410. Confirm opening hours or make an appointment to visit the gallery space: info@tuckunder.org.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Nathan Young graduated from Macalester College and will attend graduate school in the fall where he plans to study the intersections of art and economics. He still doesn’t own any works of art. Find him on Twitter: @nrp_y