The Mesmerizing Involutions of Justin Jones’ JIG

Lightsey Darst previews Justin Jones short new dances, JIG, on stage at the BLB. It's a departure for him, with tropes and trappings not typical to his work, so Darst chats with the choreographer to find out more about this intriguing change in direction.

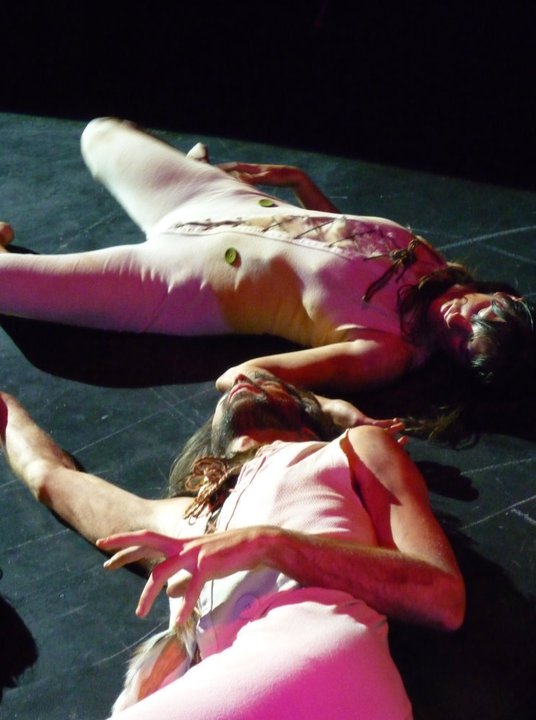

A QUICK LOOK AT JUSTIN JONES’S LATEST WORK, JIG (+Band), showing this weekend at the Bryant-Lake Bowl: A trio of dancers (Sam Johnson, Justin Jones, Hannah Kramer), dressed in dirty union suits with fur dickies, pile up on each other in shaky assemblages, brief multi-limbed creatures that unravel one into the next. Their hands reach up, in search of, then claw; they sniff and shiver volubly, then strike noble poses. What evolves (without music or any sound other than what the dancers make) is an alternation between feral animal and civilized human modes. As animals, they struggle or caress, gut emotions passing over their faces (glee, disgust, confusion); as humans, they float along in courtly dances, faces expressionless as they navigate complex orbits or balance on one foot in a stately promenade.

Filling the BLB’s tiny stage, the dancers constantly change motion and direction in mesmerizing involutions — now animal, now human, now animal. This dichotomy elicits a utopian/dystopian interpretation, but leaves a sneaking suspicion it’s not that simple. Towards the end, pretty, full-body waves seem to merge the modes, Isadora Duncan-style. That moment when one dancer points at another’s chest, stilling her: is it a finding or a death? That calm, elegant dance: is it a lie?

Rarely, the performers speak, or their gestures become pantomime, as when the three line up, shouldering an enormous gun that “goes off” in explosion sounds and slo-mo reeling. More often, though, you can recognize the sources of their dances and gestures — stiff-armed Irish dance here, drinking deep from an invisible glass there — what happens on stage is dreamlike, connecting underground and not simply to any real-life movement. There’s a feeling of enchantment about the piece, as if this dance occurs inside a glass ball, or in a moment of trance, of spirit-channeling or psychic release.

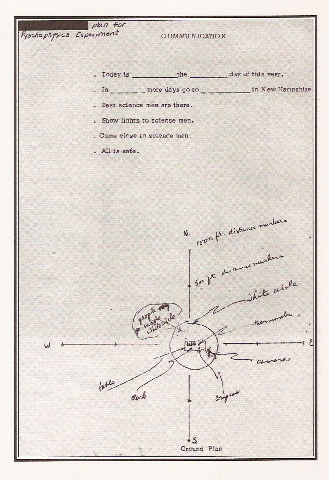

These dances first came into being as part of a larger work, Sean Griffin‘s opera, Cold Spring, performed last month at EMPAC in New York. Jones (who first worked with Griffin in the film Triangle of Need) created the dances out of themes Griffin was working with (in particular, American eugenics), making them to fit spaces in Griffin’s work (sometimes foreground, sometimes background), and in at least one case, he created a dance specifically according to Griffin’s instructions. How then does one look at this dance? Some viewers might shrug it off as derivative. But why should its origin matter? Jones created the dance apart from the rest of the opera to begin with; he’s presenting it on its own because it struck him as having its own integrity — and because he’s curious. “I want to see what this material will say out of context,” he says, calling this an experiment. “It could flop, it could be horrible.”

Flop? Really? In the polite context of the dance scene here, how can he really tell if a dance is a flop? Jones’s answer has partly to do with audience feedback — for example, if people single out one thing, one moment they liked, and that’s all they say, it’s not a good sign. “Are people having an experience that is complete, immersive, imaginative?” he asks, adding that sometimes it’s better if a show generates love and hate rather than general like. Ultimately, though, flop or not is a subjective judgment, for him arising out of discoveries he makes as he goes. “It’s about learning more about what it is I’m trying to do.”

________________________________________________________

Jones is in the midst of rethinking his past aesthetic choices, “renegotiating” his relationship with dance. And Jig, which is full of things Jones would not ordinarily do, is part of that.

________________________________________________________

What he’s trying to do, here, is different than a lot of what he’s done in the past. Jones is in the midst of rethinking his past aesthetic choices, “renegotiating” his relationship with dance. And Jig, which is full of things Jones would not ordinarily do, is part of that. He cites, as a current inspiration, playwright Young Jean Lee‘s quest for (in his words) “the thing I would least want to do next.” For example, there’s floor work in Jig, something he usually avoids, and also partnering. Usually, Jones says he doesn’t like the “narrative explosion” that occurs in viewers’ heads when they see people touching on stage, but in this case he’s willing to let it happen. The costumes are another aberration. The only trapping of the opera that he’s kept, these costumes, created by Stacy Ellen Rich, are nothing like the dance or pedestrian clothes Jones usually picks. “They’re kind of nasty — I like that about them, too,” he says. Ordinarily, he likes “things that are clean, that are very crisp. I like that [the costumes for this piece are] something I wouldn’t choose.” The dancers, too, are new to Jones (though not to audiences: Hannah Kramer is everywhere, and audiences will recognize Sam Johnson from the dance/theater quartet SuperGroup). Jones says he wanted “people who could make decisions, people who had a choreographic eye,” dancers with a theatrical awareness; he also wanted “to work with people I’ve never worked with before.”

As we talk, Jones and I spiral on into existential questions about choreography, art, and life. “Why am I doing this?” he asks. “I know that I love it, but what does it do? How does it change the universe? Does it?” Now in his early thirties, Jones is feeling the ebb of the initial push to create, what he calls “the strong aesthetic reaction;” he’s left wondering, “What is motivating me to make work now?”

Another element of Jones’s artistic turmoil is the recent birth of his first child, Lucy (with his wife, the theatrical director Genevieve Bennett). “It’s a major upheaval, in a good way,” he says, “a turning over of everything.” Altogether, Jones is ready for change: “I’m in a then what moment.”

CONVENTIONAL WISDOM SAYS THIS IS ALL INSIDE BASEBALL; why would you care? I think you care because you’re an artist yourself, in whatever medium, and you can apply these thoughts to your own practice. More to the point, you might care because viewing art is not merely a matter of directing your eyes. As a viewer, you engage in collaboration with the artist, co-creating the work that you receive. The artists’ concerns, then, are yours too — not because you need to know what game they’re playing in order to keep score, but because you are playing your own game when you view (consciously or not). You also have upheavals in taste, those moments when your usual fare and typical ways of looking just don’t satisfy you anymore.

Luckily, in dance, as Jones points out, there are endless possibilities, endless options — both for artists and for viewers. “That’s why I love dance: it’s really complicated,” he says. “There are no one-to-one relationships with the body.”

________________________________________________________

Noted performance details:

Jig (+Band), a collection of short dances choreographed by Justin Jones, will be on stage at the Bryant Lake Bowl in Minneapolis Thursday, December 16 (7 pm) and Sunday, December 19 (8:30 pm).

________________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl has just been published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She hosts the writing salon, “The Works.”