The Ghost of the Grid

Artist Ruben Nusz offers an incisive, far-ranging deconstruction of the conceptual art on view in this year's "Summer Invitational" group show at Thomas Barry Fine Arts, organized in part by a promising if challenging artist, Justin Schlepp.

RIGHT NOW, POP-CONCEPTUAL ART IS EXPERIENCING ITS MOMENT in Minneapolis – and the Walker Art Center’s brilliant Quick and the Dead exhibition, on view now, is the crowning jewel among such shows, notable for the lengths its curators have gone to make conceptual art accessible to the general public.

Defined one way, pop-conceptualism is distinguished by artists who employ popular culture to make idea-based (conceptual) art more accessible to a general public not steeped in art history. Artists like Pierre Huyghe (who once recreated the opening scene from Bambi with live animals) and Maurizio Cattelan (who fashioned a facsimile of Pope John Paul II being struck by a meteor) construct works that are, at least on the surface, instantly palatable to a wide array of audiences.

As a counter-example, Sturtevant’s Beuys Fat Chair, resonates most deeply when considered against the larger context of appropriation art and the semi-esoteric narrative of Joseph Beuys. These types of conceptual art works aren’t as meaningful when taken alone; instead, such art relies on a certain amount of prefatory knowledge of the viewer, and often represents a culmination of thought that springs from a broader cultural conversation steeped in both art history and philosophy.

Justin Schlepp, who helped organize the Summer Invitational III at Thomas Barry Fine Arts, along with gallery director Thomas Barry, falls into the latter camp: at times too precocious for its own good, Schlepp’s body of work rewards deep thinkers, especially those with arts backgrounds; but it’s equally likely to alienate casual gallery-goers who are unfamiliar with his frames of reference. Still, for anyone up to the challenge, Schlepp is one of the top conceptual artists working in Minnesota today.

Flashback to 2008: Midway Contemporary Art premieres Justin Schlepp with a solo exhibition, Mr. and Mrs. Pterodactyl. It was a complicated show, with references to “Charles Schultz, Richard Artschwager, Michael Foucault, and architect Josep Maria Jujol.”[i] I recall being drawn to an image of a Chinese finger trap placed between books. It seemed to me an especially apt metaphor for the cognitive deadfalls and mental contradictions encountered in the pursuit of knowledge — the catch-22 of trying to reconcile the pursuit of erudition with the Buddhist concept of emptying the mind of attachments (cognitive and otherwise).

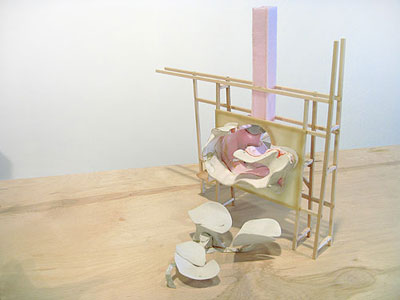

Even more impressive were Schlepp’s fabricated runners’ starting blocks, punctured with holes and circumscribed by sawdust. Reminiscent of the mental studio pursuits rendered in video by conceptual artist Bruce Nauman, Schlepp’s starting blocks epitomize the angst and frustration of practice: they’re symbols of the impotence and apprehension an artist feels when creating new work. Schlepp bores through the creative doldrums by deconstructing the opening move, the starting block. And from his work at Midway, it was clear that Schlepp isn’t a sprinter; he’s a marathon man, intent on engaging in the lifelong pursuits of art and epistemology.

With that earlier show in mind, I entered the Thomas Barry exhibition unsure of what to expect, given the change of venue. Once in the gallery, I began to see the familiar patterns in Schlepp’s work, as well as signs of his influence in putting this show together: small in scale and scope, the installation of the Summer Invitational is atypical for most group shows, in that the assemblage coherently gelled. This cohesion is likely due to Schlepp’s overarching vision — a sensibility which, to my eye, seems largely inspired by the established, early conceptual artist, Sol LeWitt.

______________________________________________________

Rashaun Kartak plays chess with her medium, anticipating painting’s endgame and succeeding in its mastery; and she makes use of her dissatisfaction with the form’s technical limitations to do it.

______________________________________________________

Most famous for his expansionist white cubes (lattices of successive squares) and for his wall drawings, LeWitt was a rare artist who bridged minimalism and conceptualism. And while he rarely executed his own ideas — he’s known for saying “execution is a perfunctory affair” [ii]— LeWitt’s formal concepts are given fresh meaning by the Summer Invitational artists Rashaun Kartak and Brian Jorgenson.

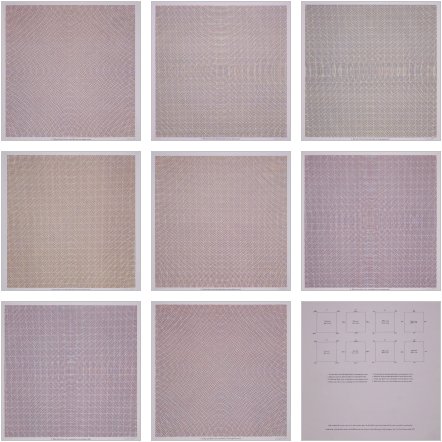

For her part, Kartak employs the LeWitt-style lattice in abstract paintings that display her mastery of acrylic paint and gel medium. Acrylics lack the velvety luminosity of oil paints, yet Kartak succeeds because she avoids adopting the conventions of oil painting, instead choosing to play to the strengths of her medium’s synthetic plasticity.

Kartak’s pastel colors subtly glow: translucent hues of green, pink, and yellow overlap and amalgamate inside Bridget Riley-esque hard lines and squares. One of the pieces on view is enveloped with a vinyl-looking, acrylic black –like the Catwoman’s leggings, as imagined in LeWitt’s dreams. Fantastic.

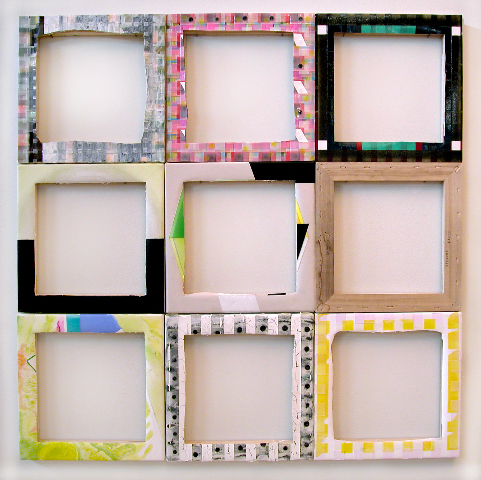

For her painting Index, Kartak echoes the frustration evident in Schlepp’s starter blocks, by cutting out the centers of nine small canvases, joined together to form a winsome cage. Like LeWitt, Kartak plays chess with her medium, anticipating painting’s endgame and succeeding in its mastery, even in her dissatisfaction with the form’s technical limitations — something indicated by her substitution of a sharpened knife for the palette-variety.

Brian Jorgenson also utilizes knives in his practice — he cuts pieces of paper into tiny triangles, and then colors each with hyper-pigmented markers before gluing them together in a composite image. Though small in scale, his collages have a kaleidoscopic gravitas, grounded in an astute sense of color, and displayed showing their delicate paper edges. Not surprisingly, one of his pieces had already been sold when I visited the gallery.

Rounding out the show is the work of Terrence Campagna, who presents the compelling results of his trash-collecting walks between his house and the gallery.

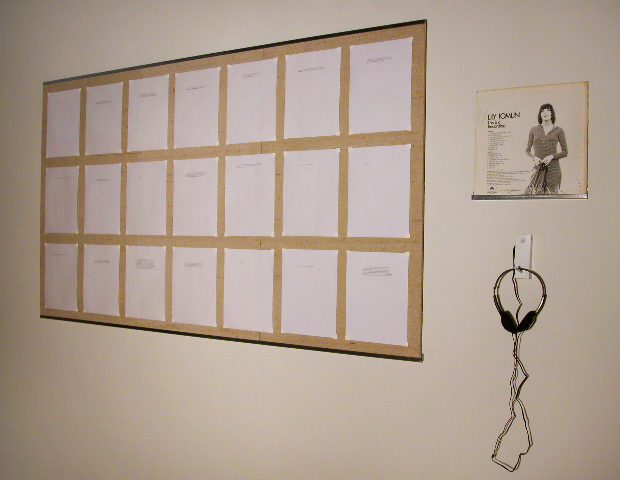

But it is Justin Schlepp who truly inspired me, with his Untitled text and audio piece. In it are typed pieces of paper, a la Robert Barry (incidentally, an artist whose work is prominently sampled in the Quick and the Dead), featuring the stuttered ramblings of an unsure mind. For example: “…butthethi_whatrthemay-themain-whatr-thetheprob-whatyouneed-thing-thingaboutit_first off what–” appears on one page, a conglomeration of false starts, of signs without signifiers. And this brings us back to Schlepp’s starter blocks. (You following me here?).

Schlepp consistently critiques the methodology of conceptualism and the limitations of language (in much the same way Wittgenstein did), while revealing the specific insecurities artists experience when attempting to make the profound manifest. After all, bringing something new into the world is no small feat.

In the Summer Invitational, Schlepp hammers this idea home with the addition of a sound collage, which features the comedian Lily Tomlin repeating the previously mentioned nonsensical phrases. If, as noted by Lippard in an essay on Lewitt, “the goal of Minimalism (or in fact of most 1960s art …) was to find a new way of making art, a new vocabulary,”[iii] then I’d argue that Schlepp is attempting to do the same thing in his self-described “hysterical stenography.”

Again, here’s Lippard on LeWitt: “Both Minimal and Conceptual art in their turns have been castigated for surrendering art to criticism and for being dependent on verbal explanations frequently proffered by the artists themselves.”[iv] Understood in this context, Schlepp turns the museum wall didactic on its head. He dissects the art graduate school prerequisite of rambling “art-speak,” while simultaneously engaging in mature self-parody (the artist has admitted that he, himself, “tends to mumble”).

For the exhibition, Schlepp also displays three open journals — like LeWitt, Schlepp’s books are an integral part of his practice. In these and other works in the show he runs through a gamut of references, from Jean Dubuffet (who coined the term “Art Brut” which focused on outsider art, the antithesis of Schlepp’s insider’s gamesmanship) to Francis Ford Coppola’s award-winning The Conversation, a film about listening, spying, obsession (which, if you ask me, are all characteristics of contemplative artists).

______________________________________________________

Justin Schlepp takes on large epistemological and art-historical concerns while, at the same time, revealing the specific insecurities facing the artist at work. After all, bringing something new into the world, aiming to make the profound manifest somehow, is no small feat.

______________________________________________________

At the end of Coppola’s masterpiece, Gene Hackman’s character believes his own apartment is under surveillance by some nefarious government entity; so, he dismantles his home piece by piece, ripping it apart like a crocodile toying with an infant gazelle. Amidst the wreckage, Hackman’s character then simply jams on his saxophone until the credits roll. While it’s a bit campy, I love this film’s ending. It’s as if Coppola’s saying that the search for meaning in this world lies somewhere beyond the realm of narcissism (that persistent feeling of being at the center of things, as if someone or something is constantly watching you, keeping tabs). In lieu of sloshing about in lonely nihilism, the filmmaker seems to suggest that there is something more out there, in art, with which we can commune to comfort us in our life’s pursuit. Whether it’s jazz or Allan Kaprow or Mozart or Truffaut, it’s art that lifts us out of our self-absorption and unifies us in our humanity.

And Justin Schlepp understands this, too, providing careful viewers with some gems to store away in their mental treasure chests. Like a Bob Dylan-esque hall of mirrors, Schlepp and his compatriots have made the Summer Invitational III a worthy visual and intellectual experience. Justin Schlepp is certainly not the most accessible sort of artist; he is, however, a very thoughtful one, and definitely one to watch from here on out.

*****

Related exhibition details:

- The Summer Invitational III is on view at Thomas Barry Fine Arts in Minneapolis until August 21.

- For his next project, Justin Schlepp is teaming up with artist Michael Mott and curatorial wunderkind David Peterson for a temporary project, Fit to Be Tried, Everything, at Least Once, at Art of This. It is part of the gallery’s One Nighter series and opens on August 8th. Do not miss this!

About the author: Originally from South Dakota, Minnesota artist Ruben Nusz was raised by cowboys and later graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Minnesota. In 2003 Nusz directed a feature-length documentary that toured the festival circuit. He has exhibited mixed-media works at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, Rochester Art Center, Rosalux Gallery, Umber Studios and the Hopkins Center for the Arts. He is one of the co-founders of SELLOUT Gallery, an artist-run space devoted to the exhibition of work by emerging and mid-career artists as well as independent curators.

[i] Quote taken from the press release of Mr. and Mrs Pteradactyl at Midway Contemporary Art, 2008

[ii] “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” Artforum (New York), June 1967, p. 80

[iii] Lippard, Lucy R., The Structures, The Structures and the Wall Drawings, The Structures and The Wall Drawings and the Books, SOL LEWITT, MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NY, 1978, p. 26

[iv] [iv]Lippard, Lucy R., The Structures, The Structures and the Wall Drawings, The Structures and The Wall Drawings and the Books, SOL LEWITT, MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NY, 1978, p. 24