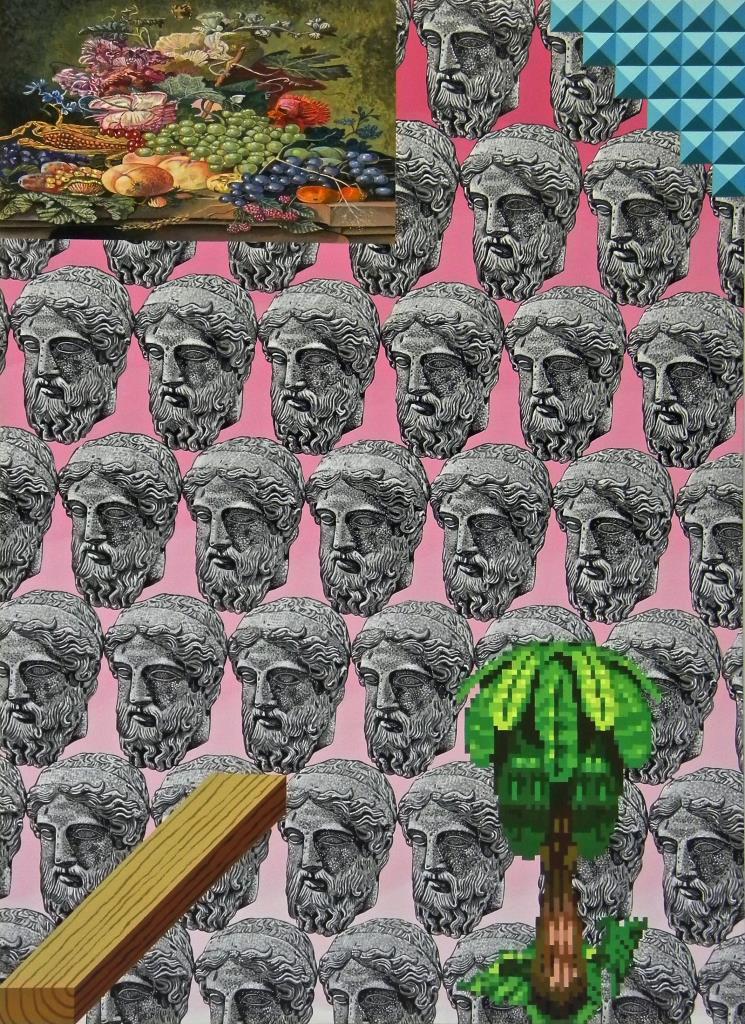

The Arcades Project

Filmmaker Kevin Obsatz on the ritual and ethos of practice in game-play, games as media of communication, and some related reflections for those who make art, at a time when the language of audience engagement is central to cultural conversation.

Art, like games, is a translator of experience. What we have already felt or seen in one situation we are suddenly given in a new kind of material. Games, likewise, shift familiar experience into new forms, giving the bleak and the blear side of things sudden luminosity.

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media

The arcade at the Ridgedale Mall in the mid-90s was called, I think, “Arcade,” and it was tucked into one of the far corners of the building, out of sight from most of the foot traffic. I remember the sign being beige and plain – rather than seeking the attention of potential customers, it seemed designed to be overlooked and ignored. It was a dim, cave-like space for teenagers to be deposited and left in the care of the glowing and flashing screens while their parents shopped.

This was the era of Street Fighter II and Mortal Kombat. Home systems were beginning to grow more sophisticated, but it was pre-Super Nintendo, a time when arcade games could still offer a more immersive, faster-pace and higher-resolution experience.

These video games were arguably the first that allowed players to develop their own expressive style of play. Unlike early arcade experiences, where virtuosity was purely a matter of reflexes and prior knowledge, these one-on-one fighting games incorporated complex, multi-stroke (right-down-corner-medium punch button, for example) maneuvers in novel combinations. Learning an array of attacks and defenses – both in theory and in practice – was the first step, but engaging another player, with their own knowledge and preferences for different moves in different combinations, added exponentially to the sophistication of the experience.

At the arcade, people, mostly adolescent males, would line up to practice these games and to compete with one another. I can only imagine the glee of the game designers who discovered that they could stoke ongoing multi-player competition, wherein one player or another would need to feed fifty cents into a machine approximately once every two minutes to keep the game going. A really popular game could, in theory, generate up to $240 a day on a real-estate footprint of only about six square feet.

I was a regular at Minnetonka’s Ridgedale Mall throughout my adolescence, and as soon as I could break away from my family, I would head to the arcade. I was fascinated by these games, but I didn’t play them myself. Even more self-marginalized then the marginal arcade nerds, I was an arcade spectator. I primarily wanted to watch people play, to vicariously experience their thrills and frustrations.

I hardly ever interacted with anyone in the arcade, I would stand back from the machines, watching over people’s shoulders. I don’t remember it being awkward, though it must have been, for the players to become aware of the skinny 13-year-old with glasses silently observing their progress. But maybe we were all awkward together there, and it was only a matter of degree. The only interactions I remember, from the many hours I spent there, were when somebody was defeated, GAME OVER appeared on the screen, and they stepped aside in case I wanted to play next. I would shake my head “no,” they would shrug, and move on to their next challenge.

In retrospect, it seems to me that I was attracted to the ritual aspect of these experiences. The arcade was a unique social space for a uniquely antisocial clientele. Those machines gave us something to stare at adjacently, an excuse to stand next to a stranger for a couple of minutes, an experience of shared catharsis that was both personal and filtered through digital avatars. Though everyone there would have denied it, in some sense I suppose it was our version of sports.

As a kid, I could hold my own on the soccer field. However, right around 6th grade most sports became “competitive” – teams accessible by tryout only – right around the time when it would have been the most helpful socially to have a collaborative physical activity with friends. I stopped playing any sports at all, and 20 years passed before it would occur to me to try anything really athletic again.

During all of those intervening years, I focused the vast majority of my energy on making and experiencing art. Making art, at least in the realm of film and video, is an immensely interactive, shared activity, which exercises the physical, emotional, and intellectual self. Filmmaking is a highly ritualized process as well, with specialized tools and talismans, invocations, drama, exertion, and conflict. But just as with team sports, there is an unfortunate divide of professionalism in the arts – a gulf that grows wider as you gain experience and skill – between the professionals and the amateurs. The further you get as a professional, the less you actually get to have fun. It’s too competitive and too expensive; the stakes are too high.

The wide appeal of the games of recent times—the popular sports of baseball and football and ice hockey—seen as outer models of inner psychological life, become understandable. As models, they are collective rather than private dramatizations of inner life. Like our vernacular tongues, all games are media of interpersonal communication, and they could have neither existence nor meaning except as extensions of our immediate inner lives. –

McLuhan, ibid

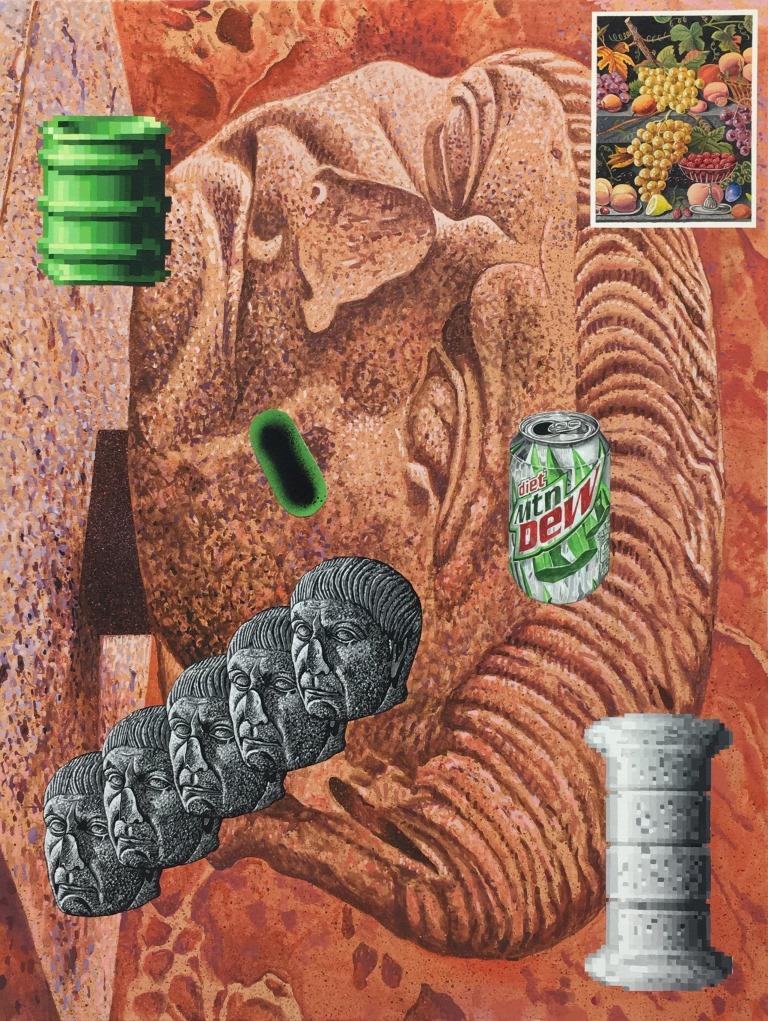

In McLuhan’s formulation, the content of the games is irrelevant, but their form as a medium of communication reflects something essential about our society, which is why we decide to care. Millions of sports fans find meaning in watching American football. Fans may articulate an emotional investment is in a specific team or player, but McLuhan argues that the form of the game is what works on their psyches – its rituals and rules, codes and symbols are all embedded in the architecture of the modern stadium, the broader brutal ecology of the game itself and the corporate commercial context. All of it presents, in my opinion, a precisely, baroquely grotesque self-portrait of our collective unconscious, for anyone brave enough to look.

In the world of video games, it’s not hard to see the appeal of Mortal Kombat to ’90s teenagers, or of Call of Duty to kids today. The aggression and killing, sure – but also the medium-specific idea of control and power exerted by the virtuosic pushing of buttons combined with teamwork and mission-based strategy. It’s not a huge leap to imagine this medium shaping the minds of the gamers, articulating a specific conception of empowerment, for all the future coders, programmers and app developers among us.

Today, fine art seems to have a much harder time than either sports or video games attracting an enthusiastic and broad audience. If games, both digital and visceral, have value as media of communication, as ritualized social spaces and ways of understanding ourselves and our lives together, what is art missing about this equation?

I am not the only arts-oriented person I know of who is noticing this, curious about it. I’ve seen a number of shows in the past decade, including separate pieces at the Walker Art Center created by distinguished choreographers David Neumann, Kenna Cottman and Sarah Michelson, that attempt to transpose at least some of the iconography and rituals of popular sports into the arena of the fine arts. And, these days, there’s a steady stream of rhetoric about audience participation, site-specific work, “creative-placemaking,” and immersion that all seems to agree, on some level, that an audience sitting passively and quietly in the dark watching art isn’t quite… satisfying, at least when set alongside the deep, passionate devotion of the sports fan and/or the hardcore video gamer.

Art and games need rules, conventions, and spectators. They must stand forth from the over-all situation as models of it in order for the quality of play to persist. For “play,” whether in life or in a wheel, implies interplay. There must be give and take, or dialogue, as between two or more persons and groups.

McLuhan, ibid

Don’t get me wrong – I love experimentation and innovation, and I appreciate the experience of going to a performance and having no idea what to expect. But I’m re-examining my own past disparagement of rules and competition – of the idea that some elements of a ritual practice should remain unchallenged and unchanged for decades or generations. There is something about the idea of clear, sharp, and universally agreed upon constraints: absolute rules, wins, losses and ties, and the sense in which all games, within a sport, are really the same game. The content of the game really doesn’t matter, the interviews with coaches and team captains before and after the games are interchangeable to a surreal degree. Hockey is hockey is hockey – as far as I can tell – and the pleasure of the form itself is instantly accessible to anyone with basic knowledge and appreciation of the sport, whether the people on the ice are professionals or 10-year-olds.

As academic and art schools at all levels grow more goal-oriented, career-oriented, test- and grade-oriented, it’s easy for students to get exactly the wrong idea about the point of any study, any skill. It’s all too easy only to see what looks like an end point, a pinnacle, rather than an ongoing, imperfect and organic practice.

One new mainstream sport to have arisen during my lifetime is MMA, Mixed Martial Arts, popularized by the Ultimate Fighting Championships (UFC) where two fighters enter a fenced-in Octagon, and the fight doesn’t end until someone “submits.” I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the UFC debuted at almost exactly the same historical moment (1993) as Street Fighter (1991) and Mortal Kombat (1992). Until recently, I found MMA completely horrifying, a sure sign of the decline of civilization. I still don’t watch the matches– there’s too much blood and too many broken bones for me. However, there is some aspect of this sport that I find undeniably fascinating, and I was recently able to find a way to engage with it. Thanks to a filmmaker friend, I discovered a Jiu Jitsu studio, joined, and have been going weekly for the past eight months or so.

Jiu Jitsu is a martial art kind of like judo or aikido, where most of the action takes place on the mat, “grappling” with an opponent. There are no punches or kicks per se, but a wide array of holds, hooks, and locks – ways of immobilizing and controlling your opponent’s body with your own.

The jiu jitsu studio feels diametrically opposed, in almost every way, to the art spaces and coffeeshops I have inhabited for the past 20 years. In the jiu jitsu studio, the rules are simple and non-negotiable. There is no technology involved at all, just a wide open padded mat on which to “roll.” Relationships and hierarchies are clear and color-coded. White belt, blue belt, purple belt, brown belt, black belt. In between belts are four stripes, which are just strips of white tape.

A class is simple. The warm-up is always the same, then the teacher demonstrates some sequences of moves and holds, which we practice. Then there’s time for minimally supervised sparring in six-minute increments. To win, you immobilize your opponent, then put them in a physically untenable position – a choke, an arm-lock – where it’s clear to both people that there’s nowhere to go that doesn’t involve severe pain or unconsciousness. This is a “submission.” The submittee “taps out,” and you reset and start again.

It’s like a game of chess played with the body. Each movement by either person creates or forecloses other possible movements, leading toward strategic advantages and disadvantages. Strength and size are important, but so are gravity, momentum, speed, flexibility, and stamina. I’m not a big guy, but any position where I’m exerting myself less than my opponent or using gravity to my advantage is changing the balance in my favor.

Though it’s technically the most violent thing I’ve ever done, I feel more relaxed in those classes than pretty much anywhere else. People who are objectively better than I am at jiu jitsu – practically everyone there – are consistently generous, kind, and even gentle. One purple belt, a guy about my size, recently said “the only ones you have to worry about are the big white belts – they might hurt you by mistake, because they don’t know any better.”

I’ve spent my entire adult life cultivating my sense of sight, as a filmmaker, and my ability to use words, as an academic and a writer. Jiu jitsu involves neither of these capacities – there’s hardly any talk except for a few minutes of chitchat before and after class, and while sparring, you barely use your eyes at all, because when your body is in contact with your opponent, you don’t need to see them to track what’s going on. In many ways, it’s an experience that is untranslatable – you could watch it and talk about it for years without getting any sense of what it feels like to participate.

It’s really refreshing to be terrible at something, and to have a very clear sense of incremental progression across a vast continuum of skill and experience. After eight months, I’m a white belt with three stripes. It could easily take me two years to get to the blue belt, and I’ve been assured that progressing beyond that involves many additional years of work. But the belts are not the point, not the reason to keep going, nor is “winning” in any particular encounter – there is always someone better and more experienced in the room. I have found that the most advanced participants are consistently the most patient and helpful. Teaching those with less experience is part of the ethos of the place, just as is testing your skills against those with more experience.

Practicing jiu jitsu reminds me of the utility of the word “practice” across different disciplines. The goal of a spiritual practice isn’t ultimate enlightenment; the practice itself is the point. Art-making as a practice has no destination in particular, but there’s value in the continuing, evolving process. Ask a black belt if they feel they’ve mastered jiu jitsu, and they’ll laugh – they are as much in the midst of a continuing evolution of understanding as anybody else.

Without a community of practice, it’s so easy to lose sight of this. As academic and art schools at all levels grow more goal-oriented, career-oriented, test- and grade-oriented, I think it’s easy for students to get exactly the wrong idea about the point of any study, any skill. Spectatorship is fine, too, but when we focus our emotional energies on world champions and movie stars, we only see what looks like an end point, a pinnacle, not an ongoing, imperfect and organic practice.

The unexpectedly beautiful thing I witnessed at the arcade, back in the ’90s was a group of kids hungry for a practice, wanting to find a set of skills and a world that they could put their emotional energy into – finding and creating that ritual space without necessarily being able to describe or articulate what they were creating, or why. (Most of this sort of gaming has since moved online, though I know that some groups still meet in person to compete and “quest” together in the more expansive games.)

Filmmaking can be like that, learning by doing, alongside unofficial mentors and elders. Competition, in its proper place, is a byproduct of practice, a way of measuring progress, but it’s not the goal, not the point. A film can be a living thing, a moment in the practice of a community of filmmakers. Though color-coded belts would be more efficient than all the unofficial signifiers carried by gaffers, grips, production managers, and camera crews.

When artists or museum administrators talk about trying to engage audiences, it seems to me like a profound misunderstanding of the purpose of art and the role it plays in people’s lives. If I only get to see the artist across a gulf of professionalism and stardom, if I can’t even feel connected in the same way I can relate to Peyton Manning by buying a jersey and throwing a football around my yard, why should I care what they’re doing up on stage?

Whereas with jiu jitsu or video games, getting involved is easy – I just have to start showing up, learn a few basic parameters, feed the metaphorical quarters into the slot, and press play. It’s going to be a disaster the first few thousand times, no doubt, but there’s no question that I’m welcome to try, and that the black belts in the room are at least willing to give me a roll on the mat and teach me a few things.