Moira Villiard: People and Space

A conversation with the 2022/23 MCAD–Jerome Fellow on elevating Indigenous and greater Minnesota narratives, co-creating with community, and how media makes meaning

Melanie PankauYour practice encompasses public art collaborations, installations, and community intensive exhibitions. As a multidisciplinary artist and community organizer, you mention you use your work to elevate Indigenous and greater Minnesota narratives that explore the nuance of historical community intersections and promote accessible community healing spaces. Could you talk about how these narratives unfold in your work and the vital spaces they create?

Moira (miri) villIardIt maybe starts with me as an individual; I’m a mixed heritage American. A lot of us are. With being mixed, there’s both intersections between and separations of identities, and it’s the history of those intersections and separations that drives a lot of my work as an artist. I naturally tend to think in flow charts and diagrams; I’m drawn to thinking about the places where ideas and people overlap.

As I piece together parts of my own identity, I find myself having a lot of questions about history. My approach to Indigenous storytelling is as a tribal direct descendant (a person with no tribal citizenship, despite having one or more tribal citizen parents), which comes with its own complications that I don’t think a lot of people realize.

How all this connects to my work is through my desire to create space for people to explore their own overlaps in identity and history, whether that’s through conversation with each other while working on a mural together, or more formally in curated events and experiences. We develop some aspects of our identity, while being born into or prescribed other parts of it. We often have conflicts within our own identity that cause us shame or grief or confusion. For how much of an impact these conflicts have on us as individuals and communities, I feel like there’s never enough safe space to discuss any of it. I use my exhibits and arts experiences to change that.

Some examples include the Chief Buffalo Memorial project, which I’ll talk about a little later in this interview, and my traveling exhibitions Rights of the Child and Waiting for Beds. In the latter examples, I’ve done a lot of research and disseminated data into key points, which I then turn into artfully designed posters. The posters are displayed between artwork (generally paintings or mixed media pieces), which is installed in a wide range of spaces and paired with community programming. The posters offer a base-level education on the topics explored in the exhibits, and give audiences the tools to have meaningful and critical conversations about said topics.

Rights of the Child focuses on global childhood norms as well as human rights treaties that the United States hasn’t ratified, and the overall justification of controversial policies for the sake of “future generations”. The exhibit is usually installed in conjunction with work by youth, because often children’s rights are a subject that gets discussed without the presence of youth voices. My goal is to connect audiences to global concepts and help them apply them to the local community issues they face.

In Waiting for Beds, my focus is on highlighting the absurd normalization of “waiting” for crisis care beds to open up. “Waiting for a bed” is a phrase used in multiple fields, from domestic violence, to homelessness, to addiction care, to mental wellbeing and hospitalization. Many people who wait for a bed die while waiting. The exhibit is meant to pair data with lived experiences, and the exhibition itself contains sections for community submissions, where people can submit objects or artwork tied to their experiences of being institutionalized or caring for people in these settings. My hope is to create an exhibition that’s impossible to look away from—to create a space where it’s impossible not to feel compelled to change the systems under which we all live.

The common thread in my work is community engagement, making sure there’s space for people to insert themselves and share perspectives on the broader topics at hand in each exhibit or artwork.

MPYou describe: “My medium is people and space.” I’m curious how these two “materials” are at the heart of your practice?

MVThey’re rooted in how I define art. If I had to define art in this moment, it would be “human ways of being”, with an emphasis on the action “being” and an implied noun of “people” within an implied setting of “space”.

This definition emerged partly because I don’t have a formal arts education. I’m self-taught, to the extent that I have many sources of inspiration and education that I pursued on my own time. Stylistically, I feel my use of color and my use of space stand out most as an artist. I’m drawn to surrealism as a means of layering different times and places into single imagery. In college, I majored in Communicating Arts, but I focused on the theory side of communication more than my peers did. I have a fascination with architecture and the built worlds around us. I was really into Marshall McLuhan and his laws of media, “media is the message” type stuff.

The study of media ecology in particular really influenced how I think about art. I believe that the media used and the organization of space is what makes meaningful art—it’s not always the subject matter of the work itself. What does work exhibited in a coffee shop communicate vs. the same work being hung in a high-end gallery in New York? How do we assign value to art? And what does it mean that “art” itself is a word that doesn’t exist in many languages around the world? These are some of the questions I started to reflect on as I began pursuing a career in this field.

The deeper into my career I’ve gotten, the harder it’s been to align myself with a single type of artistry. What do you call an artist who creates not just paintings, but films, murals, installations, writing, graphic design, etc.? I think for me, I had to take a look at what connects all of these mediums to identify what my actual medium is. The thread is simply space and people’s engagement with it.

It shows up multiple ways. I spend a lot of time implementing art in non-traditional spaces and figuring out ways to engage the community that frequent these spaces in the process of creating or influencing my/our work. I experiment a lot and am constantly trying new mediums in my work. I’ve taught art classes to all ages and consider those to be my “art” just as much as the paintings that I make because, at the end of the day, art to me is experience. Art exists as not just the final image or film or performance, but all the moments leading up to it, and all the moments that follow.

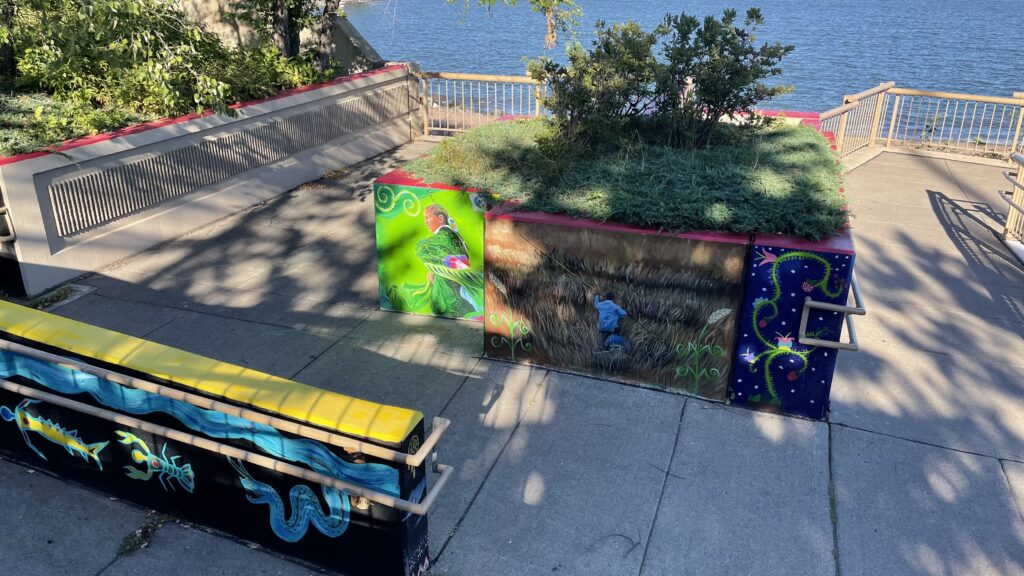

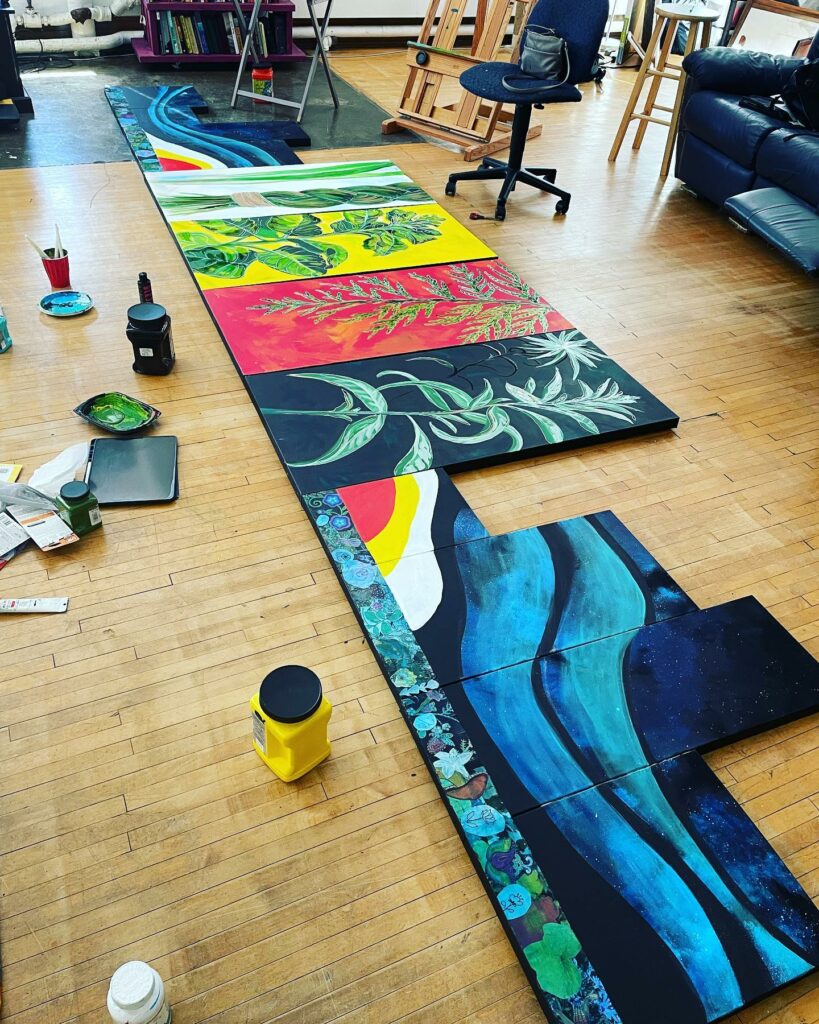

mpFor the past several years, you have been the activist and project director behind the Chief Buffalo Memorial Murals in Duluth. Could you tell us more about this project and how it has evolved since its inception?

mvTo bring us back to your first question about how my work seeks to elevate overlapping historical narratives, the Chief Buffalo Memorial project has been a key part of that work. It’s an effort to bring to light the history of Chief Buffalo, who played a role in making sure the Ojibwe people weren’t forced further west, and also is the reason a lot of non-Native people were able to live in cities across the region. In a perfect world, non-Native, European-heritage people would know Chief Buffalo’s connection to Duluth and maybe even feel compelled to celebrate and acknowledge his contributions to the establishment of towns that exist today around Lake Superior.

A lot of European-descent people in the community have an attitude against sharing space for history-telling. They genuinely don’t realize that Native American history is our collective American history. The story of Chief Buffalo serves as a thread that connects the past to the present of where I live. Nobody would be able to live here on Turtle Island/in the United States without the treaties that are the law of the land. These treaties gave permission for people to settle in many places around the United States.

I’ve heard a lot of folks make the point that those documents are “old” and don’t serve much purpose today. I always wonder if those people also feel the same way about the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence? Are those documents just out of date too, should we simply disregard them? Additionally, treaties afford rights to settlers, not necessarily to Indigenous people (there’s a difference between “reserving” inherent rights and granting rights that didn’t exist before). So again, a major goal with this project for me was to create a space where people could learn about Chief Buffalo in an approachable way, but also garner better understanding about the stories that make up our existence as a community.

It started as a pilot opportunity, where I facilitated community painting sessions to paint three of the many walls in the walkway. I got asked time and time again when the next painting session was going to be, and eventually got more connected with folks like Bob Buffalo and the Indigenous Commission, all of whom wanted to see more artwork go up in the space. The pilot project turned into a multi-year effort and lesson in public art implementation.

Since 2019, we’ve had over 500 volunteers and community members come out and help support this project through events/powwows on site or painting on the wall itself. I think involving people in such extensive ways in the process of creating the work also has made it somewhat of a protected space. People use it now more than ever and care about it. The gray walkway that was, in truth, a little scary to use, has now become a site for community activation.

MPYou were recently a Salzburg Global artist-in-residence at the Schloss Leopoldskron in Austria. What did you work on while you were in residence? What was the most impactful part of your experience abroad?

MVI’ve never gotten to travel much internationally before this year, and it’s been a life-changing experience that I’m very grateful for. I was able to go to Mexico City for a week in November, and then shortly after spent my time in Salzburg for another two weeks. Soon I will have the opportunity to spend two weeks in the regions of Israel and Palestine to learn more about the holy sites and occupation.

The most impactful experience for me was honestly the break from the project of America. It’s been less about producing physical work and more about research and experience outside of the bubbles I grew up in. I understand myself and my background in the context of small towns in the Midwest, but each of these trips has really transformed how I see myself in a world context. It brought on new fascinations and realizations, especially around topics of race and justice, around Indigeneity and colonization.

In Austria specifically, I spent a lot of time connecting with folks, including artist and regalia maker Adrienne Benjamin and writer Dina Mousa. You can read a bit more about that specific experience in the write-up I did for Salzburg Global Seminar.

MPWhat’s the most challenging part of your studio practice?

MVI live with chronic pain. Like a lot of people, I don’t have a formal diagnosis, but it’s something in the vein of fibromyalgia and EDS, paired with just being very tall and having trouble putting on both fat and muscle. I have a physical pain issue paired with a severe migraine disorder that’s afflicted me since preschool (which I at least now have a diagnosis for).

I first started having issues in college. I’d lost the ability to use my dominant arm in its entirety for roughly 3 years. I used physical therapy, occupational therapy, massage, various hot and cold treatments, supplements, pain meds, surgery, steroid shots, etc., you name it. It never fully went away, but now that I work for myself instead of going to school or a day job, I’m able to manage the pain flare ups and self-regulate much better.

It felt like I was cursed to not be able to do art ever again during that time. I used my feet, I used my left hand, I turned to public art and asked the community to help me paint my work—how I inadvertently launched a lot of my community-engaged practices. I would design outlines of images and direct community members to help do the physical labor of painting. My feelings shifted slightly about being cursed. It felt like the real curse was more or less society’s assumption that you need to have a day job in order to sustain yourself as an artist. I needed to quit virtually all the “normal” paths in order to better cope with my body’s needs.

What the physical issues have meant for my work as an artist is that I don’t get to spend much, if any, time “practicing” in the traditional sense. I had to give up “sketching” or creating drafts of work. Everything I do is basically the first and final draft wrapped into one. It’s nerve-wracking and vulnerable for me, because it comes with a constant awareness as an artist that I’m not the most technically proficient and I may never be. But there’s also something freeing about being able to go into a space and have my artwork, these parts of myself, be openly incomplete.

Additionally I struggle a lot with my recovery from childhood traumas, making sure I get therapy and keep tabs on my own mental health, which maybe isn’t terribly uncommon for artists in general.

MPWhat artists, writers, musicians, exhibitions, performances, films are inspiring you right now? And why?

MVInterestingly enough, I don’t garner a lot of inspiration from other artists so much as I do research. When I do get time to read, I like to read about the history of communities, objects, economics, institutions, and social constructs, and I think that influences my work the most. Or I will put on documentary series when I’m working on art and have those play in the background.

I’m largely influenced by people around me—my wonderful mural crew on the Chief Buffalo, including Michelle Defoe, Sylvia Houle, and Awanigiizhik Bruce. Emerging artists also inspire me a lot. And the youth that I get to work with as part of some of my teaching gigs. My “art partner” Carla Hamilton has been a big influence in the last few years. We’ve been working on an exhibit called Waiting for Beds, which this fellowship is partly supporting. She’s a mixed media artist in the truest sense of the word, incorporating a lot of elements of collage and found media into her work. I’ve started using fabric and ribbon in my work as a result of spending time and collaborating with her.

Outside of my own circles, I really admire the work of contemporary painters like Arcmanoro Niles, Avis Charley, and Njideka Akunyili Crosby. I’m fascinated with work that explores domestic life—the everyday stories of community and friends captivated in surrealism. I love artists who can mesh together technical proficiency in realism with experimentation with color or time or style.

MPHow has winning the Jerome Fellowship affected how you approach your work?

MVI think the most helpful piece has been the financial support for my next big project. It’s been amazing to just have funding to push the boundaries of media I use in my work, and to also be able to offer stipends to community members for contributing to the project. As part of my Waiting for Beds exhibition, I’ve been able to frame precious objects from people’s struggles with addiction and homelessness, so when the loan of their items and artwork is done, they will have a way to display these items in their own home.

It’s also been a confidence booster for me, especially as an Ojibwe heritage artist. On a broader level, I think Native artists run the risk of being pushed to only make art that reflects their cultural heritage or uses “traditional” materials. And often artists of color in general don’t get to make “whatever” they want in the same way that prominent white artists do.

It’s a hard tension to describe. I just have felt affirmed since being selected that I can make art that speaks to me, to all the different parts of me, and to all of those parts as they’re reflected by my communities. I feel affirmed that my technical abilities play a role in my work too. I don’t often get selected when I apply to fine art opportunities, often because my work is too “community-engaged” or sometimes a little rougher around the edges. It’s nice to feel a little more like I’m on the right path with my art.

MPIf you could describe your work in one word, what would it be?

MVAlive.