Strong Currents

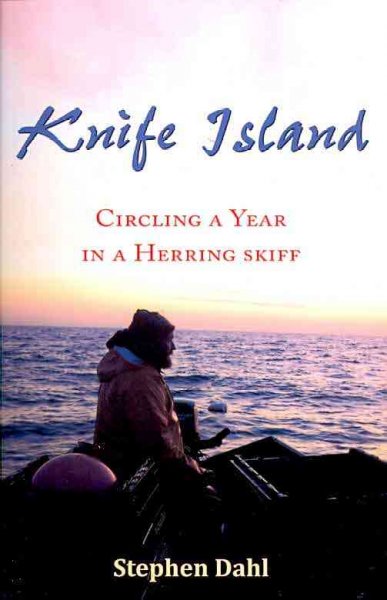

Stephen Dahl, author of the new memoir, KNIFE ISLAND, chats with writer Hannah Dentinger about reading, writing, and fishing the waters of Lake Superior's north shore.

KNIFE ISLAND: CIRCLING A YEAR IN A HERRING SKIFF, IS A SLIM, SPARE VOLUME that comprises meditations spanning a year spent fishing Lake Superior for herring, from Two Harbors to Knife River. The entries describe with precision the days between ice out in the spring and ice’s winter return, days that range from the mundane to the transcendent, colored by everything from politics to poetry.

Stephen Dahl has been fishing these waters for more than 24 years, and he looks the part: full, dark red beard, creases at the corners of his eyes from laughing or squinting into the sun, hands weathered and permanently tanned. This fisherman, though, has a master’s degree in Scandinavian literature; he was also, at one time, a vocational counselor.

Born in New Auburn, Wisconsin, Dahl writes of dairy farming country with affection, but notes that “deep down, even in those naïve, unformed kid cells and nerves, I knew it wasn’t my place.” A camping trip in Knife River, Minnesota, after college, convinced him that the north shore of Lake Superior was his spiritual home.

And fishing?

“It’s funny,” Dahl says. “Being on the ocean water, the sea…was it the Nordic genes in there that just popped out? I don’t know.”

Dahl didn’t find his niche immediately, actually. But he was always interested in Nordic culture: he spent a year in a University of Wisconsin program in Copenhagen and then, after college, he worked as a farm worker in the far north of Norway.

“Norway has a labor shortage in the summers,” Dahl notes. “In the job application process, they said, ‘Are you willing to go to north Norway?’ and I said, ‘Of course,’ not realizing what that really meant; the difference [between the southern and northern regions of Norway] is like going from Key West to Duluth. I was about a thousand miles above the Arctic Circle. The sun doesn’t even get close to the horizon.”

Dahl went on to gain a master’s degree in vocational rehabilitation and a license to dispense medication in intermediate care facilities for the disabled. (“Technically, I think I’ve been enrolled in five different universities,” he recalls.) He says he worked in those fields for as long as he could but, eventually, he got restless.

“I’m a burnt-out human service worker,” he shrugs. His next step was a leap — to commercial fishing. “I just wanted to fish. I wanted to get into it,” he explains. After “hook[ing] up with a boat in Port Townsend, WA” that was going up the Inside Passage, “I jumped ship at Sitka with forty bucks in my pocket and found a job on the island.” That was attempt number one to land a fishing job. Attempt number two came when Dahl accepted a human services job in Duluth “just to get up here.” Once there, “I just looked around and got a hold of Sivertson’s.”

To fish commercially on the north shore of Lake Superior, hopefuls must spend two years apprenticed to a master licensee. Dahl served out his time with Sivertson Fisheries. He was paid in “crew shares”– that is, in fish. “But you know,” he says, “in the fishing world, that’s just how it is. Everyone takes on the risk.” According to Dahl, shared risk is just part of what you sign on for, even when you’re working on larger craft. “The second time I went to Alaska, it was basically a bust. El Nino hit, and the Bering Sea was, I think, close to ten degrees warmer than usual. My airplane ticket was $1,100 and I made $2,000.” Dahl laughs, “That’s fishing!”

In Knife Island, Dahl recounts a number of the stories — some funny, some poignant –told to him over the years by other seasoned fishermen, men whose quirks seem to match their names. (My own favorites are a pair of brothers called Kenny and Squeak.) The susceptible reader could end up idealizing this as a field populated by old-fashioned individualists, who are nostalgic for a bygone era in which meals depended more on nature’s whim than on the ingenuity of, say, Monsanto.

But Dahl is quick to dispel the idea that commercial fishing is an old man’s game. “Everybody thinks they’re all elderly. It’s not that way anymore; we’re not the last of the Mohicans. Fact of the matter is, there are only 25 licenses available; [at any given time] there are a number of people who’ve finished their two years’ apprenticeships, who are waiting for [a spot to open up],” he explains.

What’s more, Dahl says, “I cannot keep up with my market. What’s happened is this: the local food, slow food movement, the organic food movement, and in our case, the growing market for wild-caught [fish – they’re all booming]. The demand has just taken off.”

______________________________________________________

Dahl’s entries have the immediacy and freshness of pages spattered with spray from the gunwales — ‘Yes, lift the net up over the bow. And there, the flash of silver herring below in the clear, cold water. And now the sun peeks through the fog to warm my face.’

______________________________________________________

Dahl mentions one client, in particular — the New Scenic Cafe, near Two Harbors — that he says epitomizes his current pool of buyers. “That’s the niche,” he says. “People come in for as much local, organic food as [owner] Scott [Graden] can get.” And, Dahl continues, “That’s the way it should be. I mean, import all your fish from China? Is that stuff looked over at all? Is it caught in a sustainable manner?”

Dahl’s broad, geopolitical perspective on fishing informs Knife Island; and the author doesn’t disguise his political views, writing on one occasion, “I have a visitor in my skiff this morning. An unwanted person. The president. […] I have two nets to lift yet and I don’t think I can endure him anymore. I need to get him out of my skiff.”

In that same passage, Dahl muses on the idea of heaving a cement block over the side, symbolically dumping his anger and frustration with Bush administration policies — but then, he reconsiders. “I’m too cheap to waste a good cement block on him,” he writes. “I need to focus on the work I have to do, and on the beauty around me. Yes, lift the net up over the bow. And there, the flash of silver herring below in the clear, cold water. And now the sun peeks through the fog to warm my face.”

The fishing season’s long days and intense physical labor meant that Dahl had to save writing Knife Island for his winter hiatus. Yet, his entries have the immediacy and freshness of pages spattered with spray from the gunwales — something he managed to hold on to by making quick notes during his busiest time.

“You’re too tired to write every night, so two sentences or two words will cue that mental image” when, in January, February, and March, there is time to “sit down for half an hour here, fifteen minutes there. I’m hesitant to sit down and tinker until I’ve ruminated, rolled it around in my head. The problem I have with [my] writing is it’s too Norwegian-esque; if anything, I have to go back and add a little body to it.” He jokes, “I’m the antithesis of Proust.”

Dahl and his wife, Georgeanne Hunter, a musician and teacher, live north of Duluth in a house they built together. In addition to mornings spent solo in a skiff and afternoons walking their dogs in the woods or honing lines, Dahl serves as township supervisor, collaborating with his neighbors on projects that include administering the area’s unique charter school.

“[My life] may appear solitary, but it isn’t. Certainly, out there [on the skiff] it is, but the rest of my day isn’t. That’s another thing about youth — you have these romantic notions of this kind of life, of being this aloof hippie out here. But then you […] realize how important community is. I feel blessed, honored to be part of it; it’s so important to be involved.”

As Matthew B. Crawford, author of Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry Into the Value of Work, discovered when he abandoned a postdoctoral fellowship in political philosophy for motorcycle repair, the kinds of careers to which many are encouraged to aspire — sedentary, cubicle-bound — are an unnatural, even self-destructive, path for some.

Says Dahl, “It took me a long time to figure out I’m happier working with my hands; I love the work I do. Then, in the evening, I’ve got The New Yorker, the newspaper, my novels, or writ[ing]. I’m better off, and my mind is in a wonderful place, after a satisfying day of bringing 30 pounds of fillets to the Scenic Cafe. That makes sense to me, whereas being a burnt-out human service worker… there wasn’t anything left to me [at the end of the day]. It took me a long time to figure this out about myself, and what I’m doing now isn’t for everyone — but I love what I found.”

______________________________________________________

About the author: Hannah Dentinger lives in Duluth and writes on art and literature.