Series:

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest Editor

Series: Unreasonable UnarchivesGuest EditorXiaolu Wang

When Gayatri Spivak asks, “Can the subaltern speak?”, the subaltern is a position, not an identity. No one can claim, “I am subaltern.” If it’s a position, it is also not always continuous. If the subaltern cannot be described, it can speak through dying, disappearance, and fugitivity.

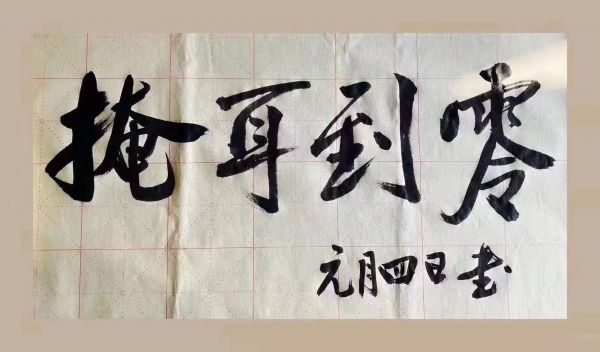

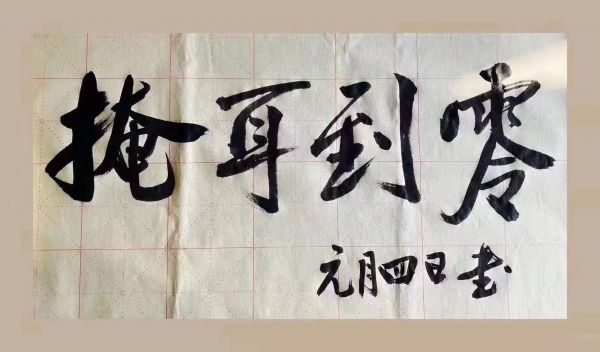

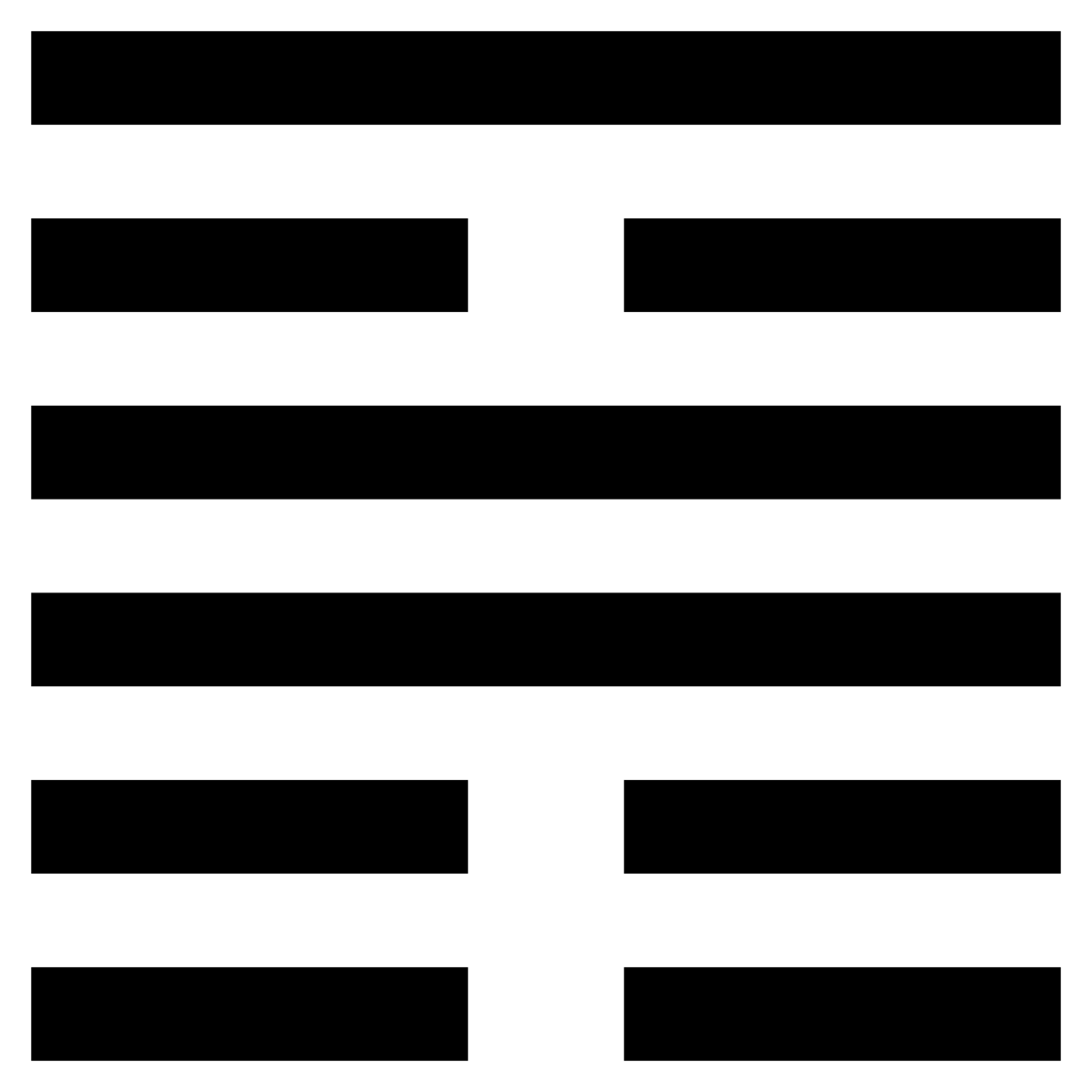

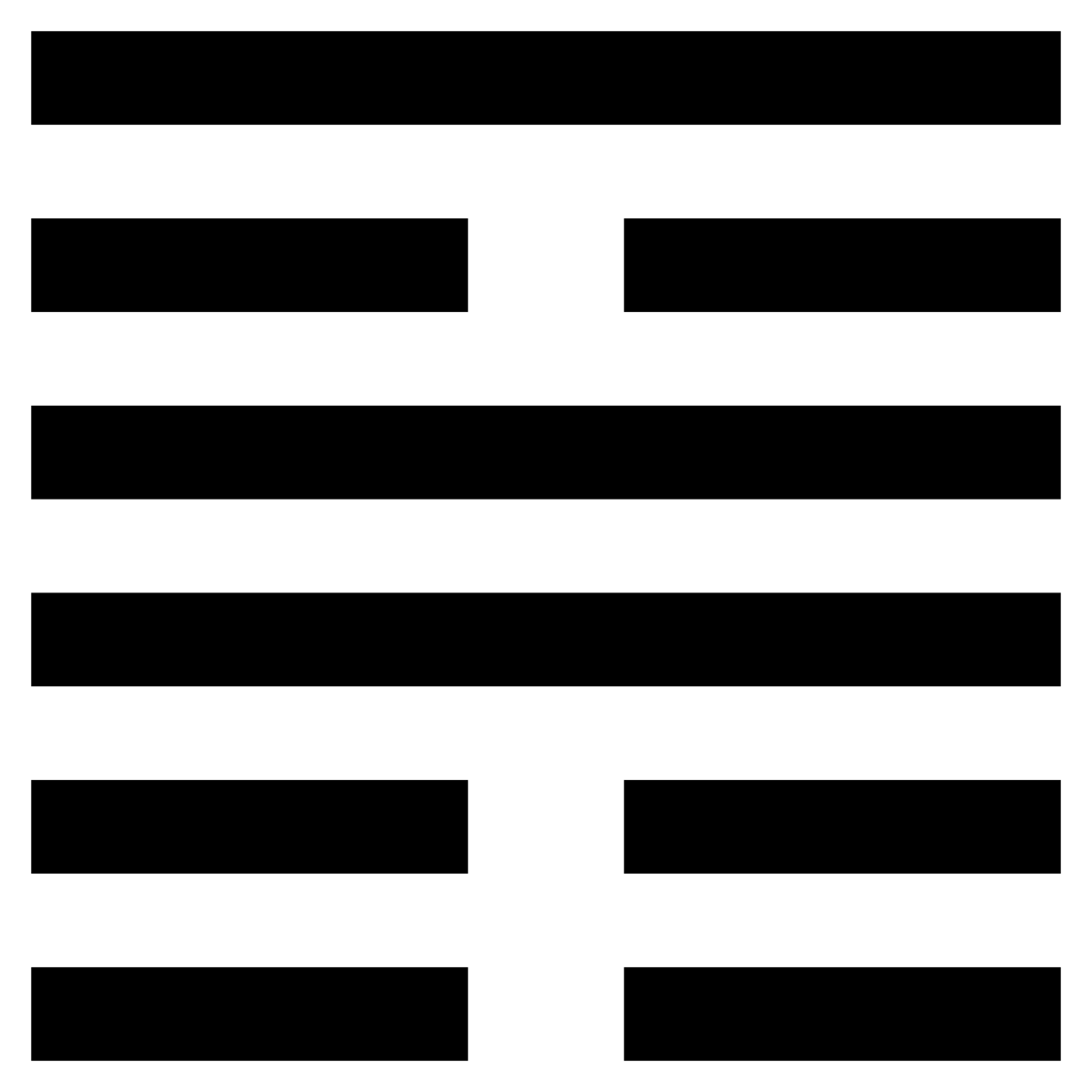

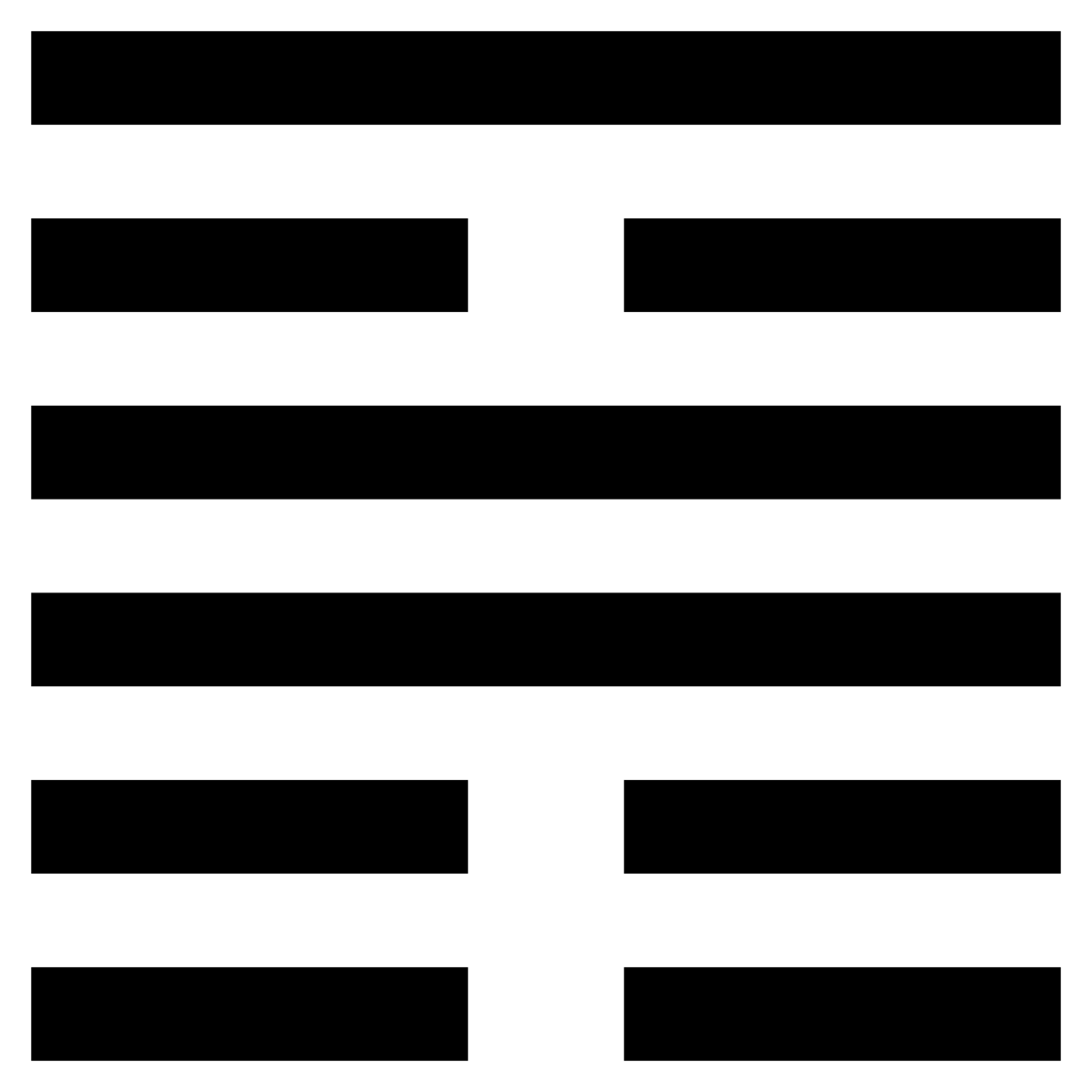

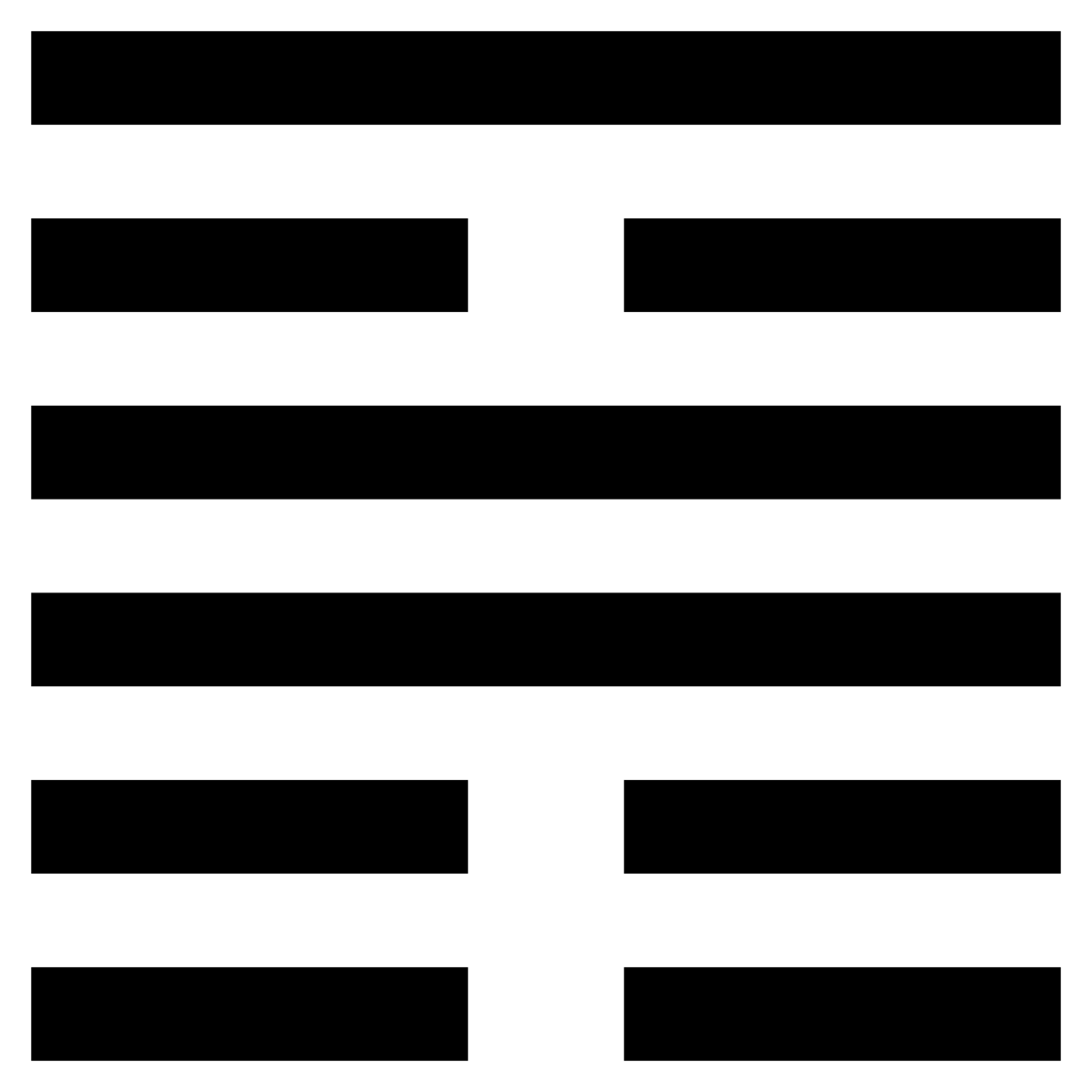

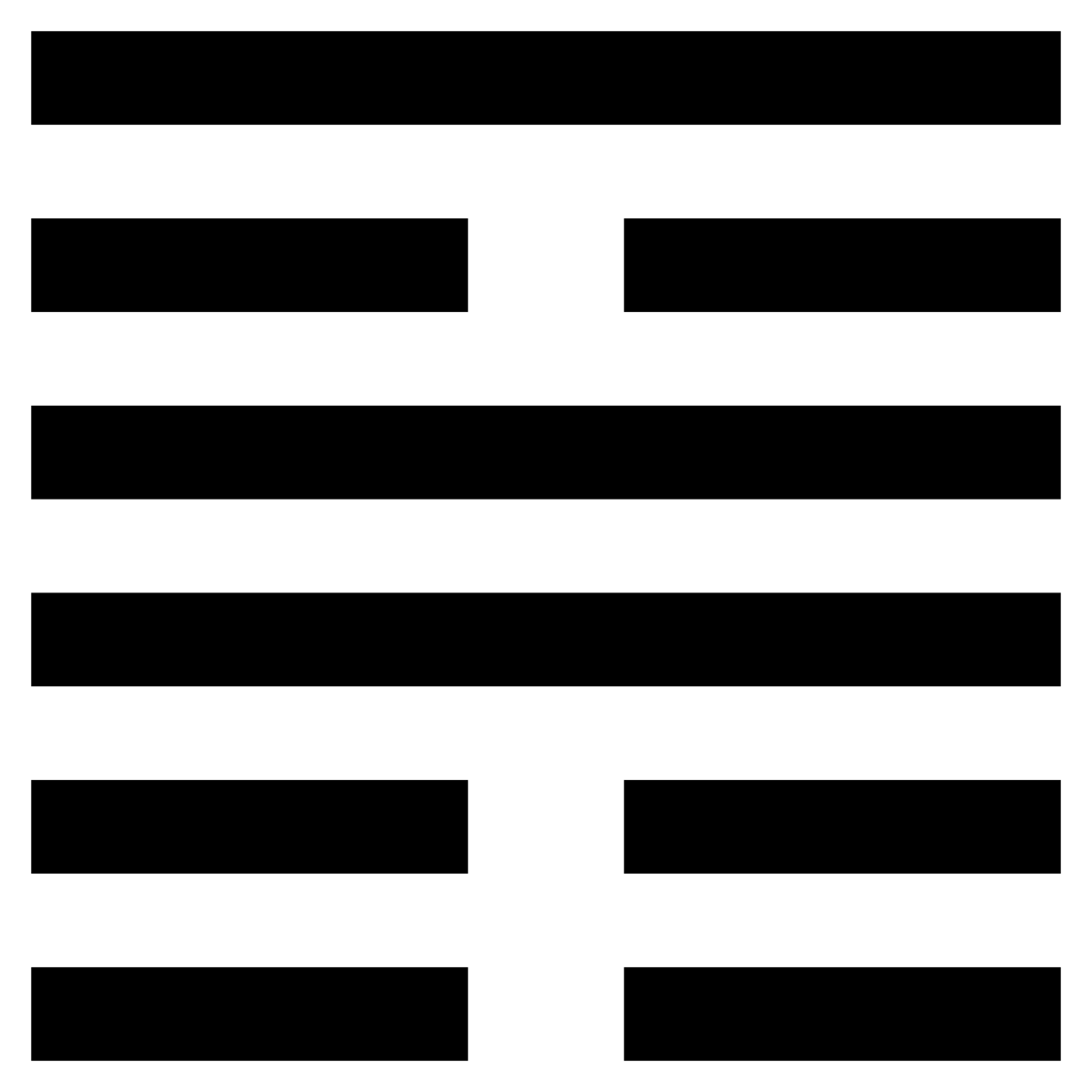

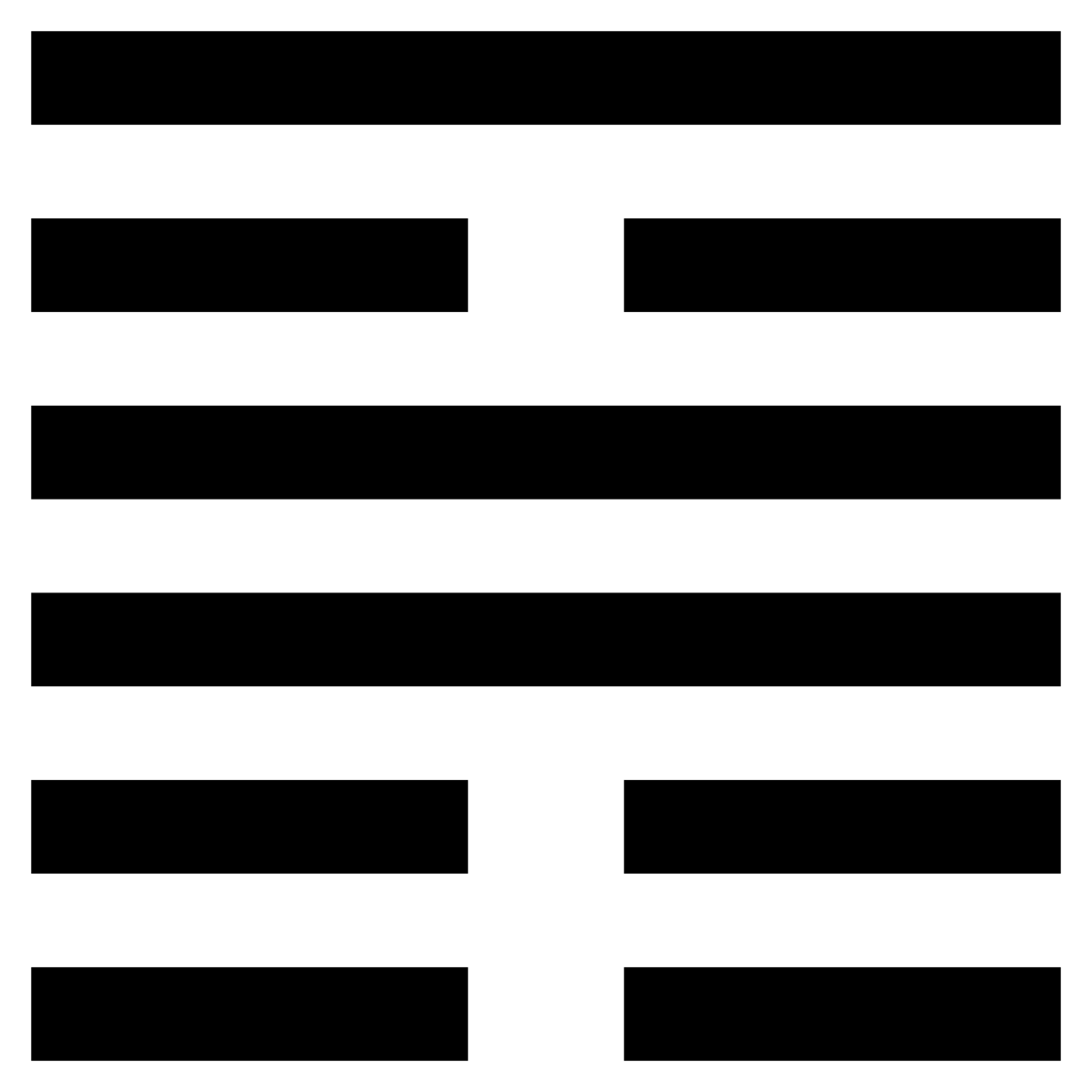

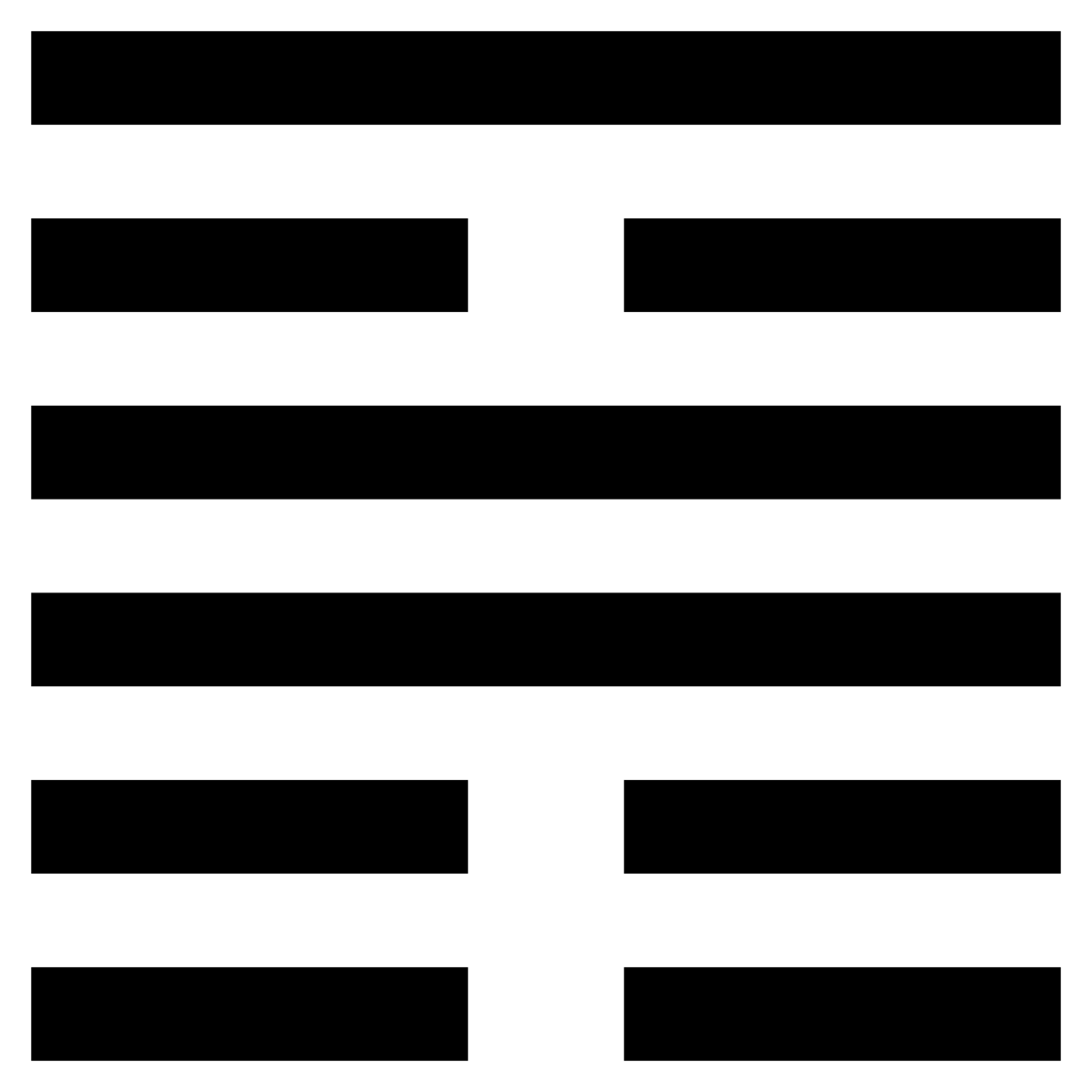

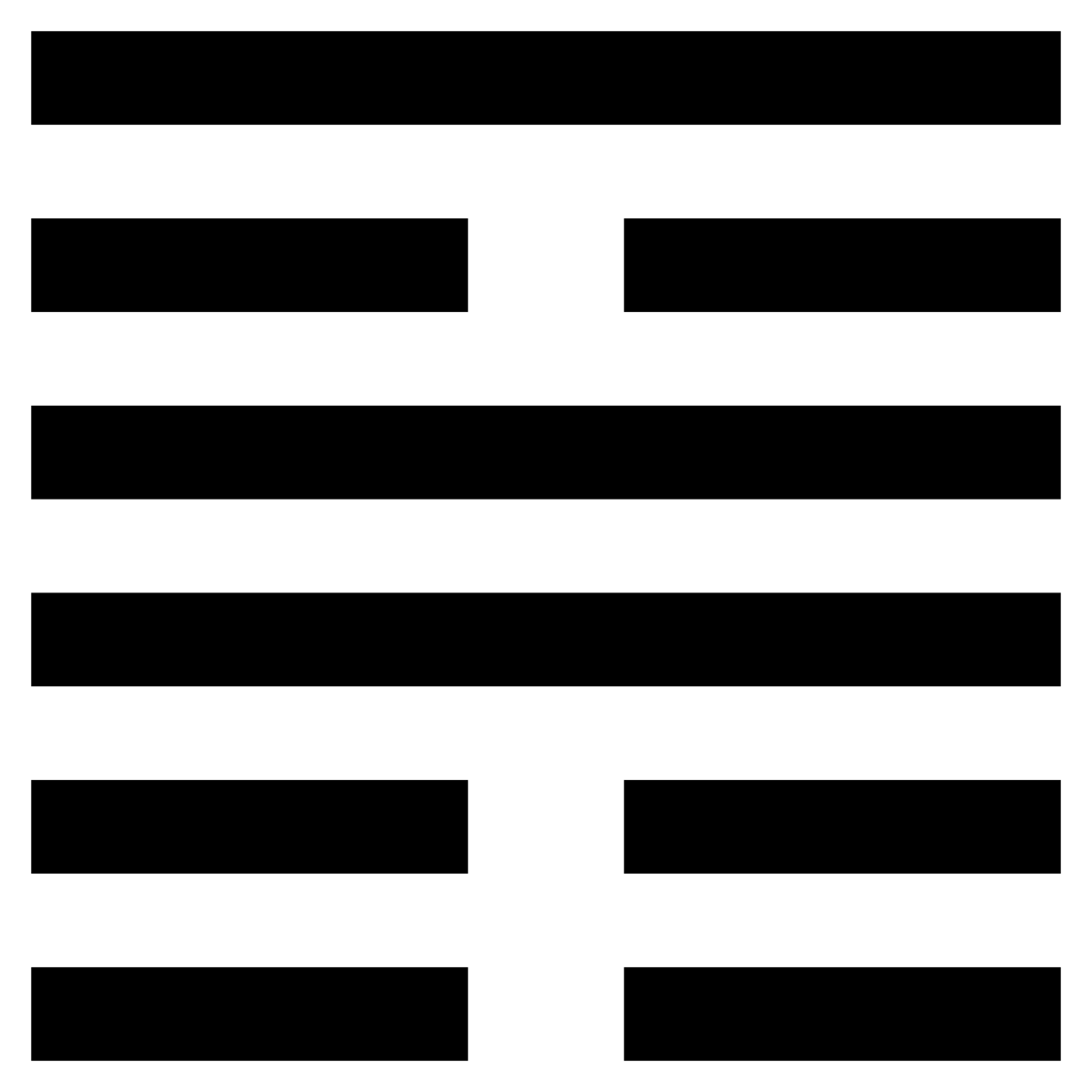

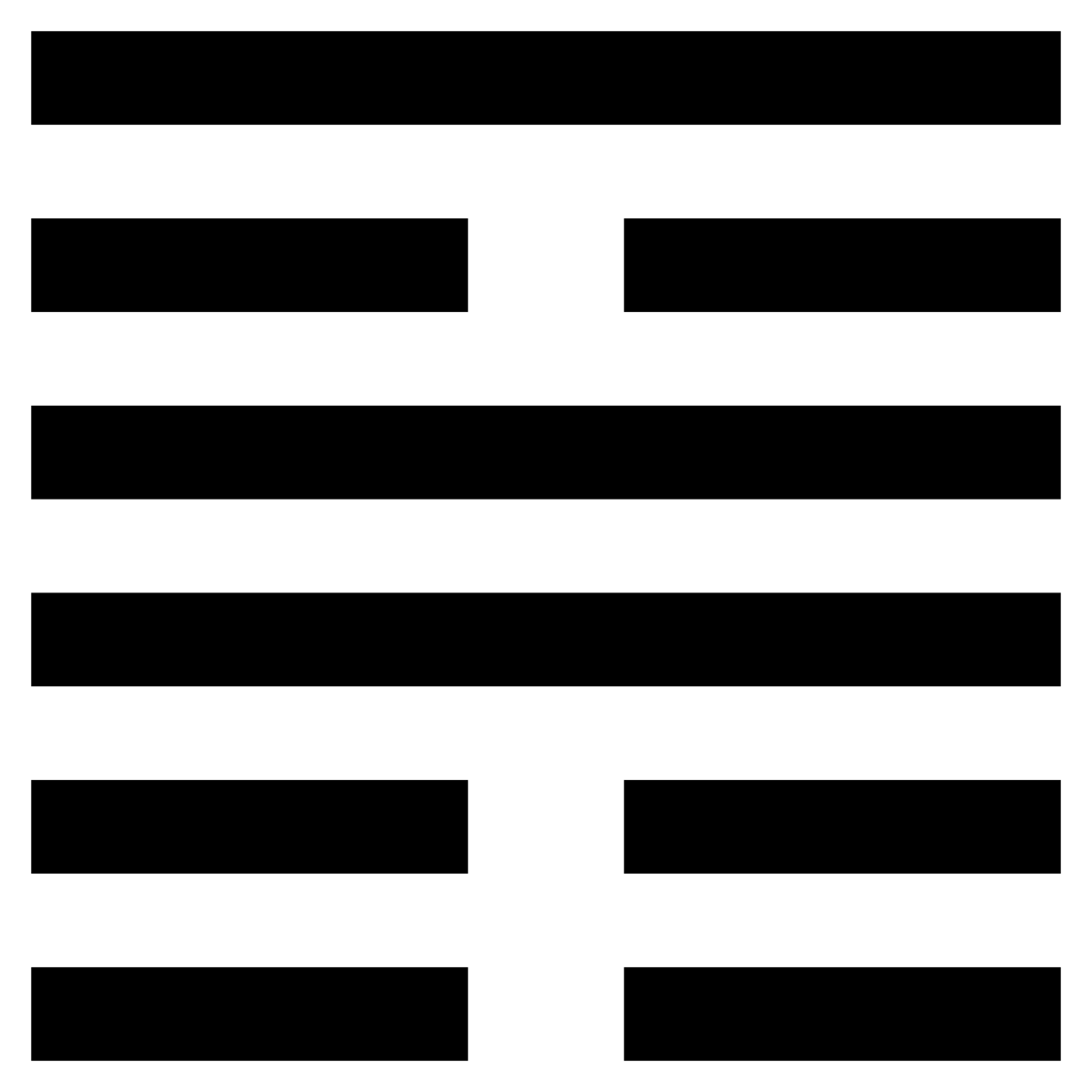

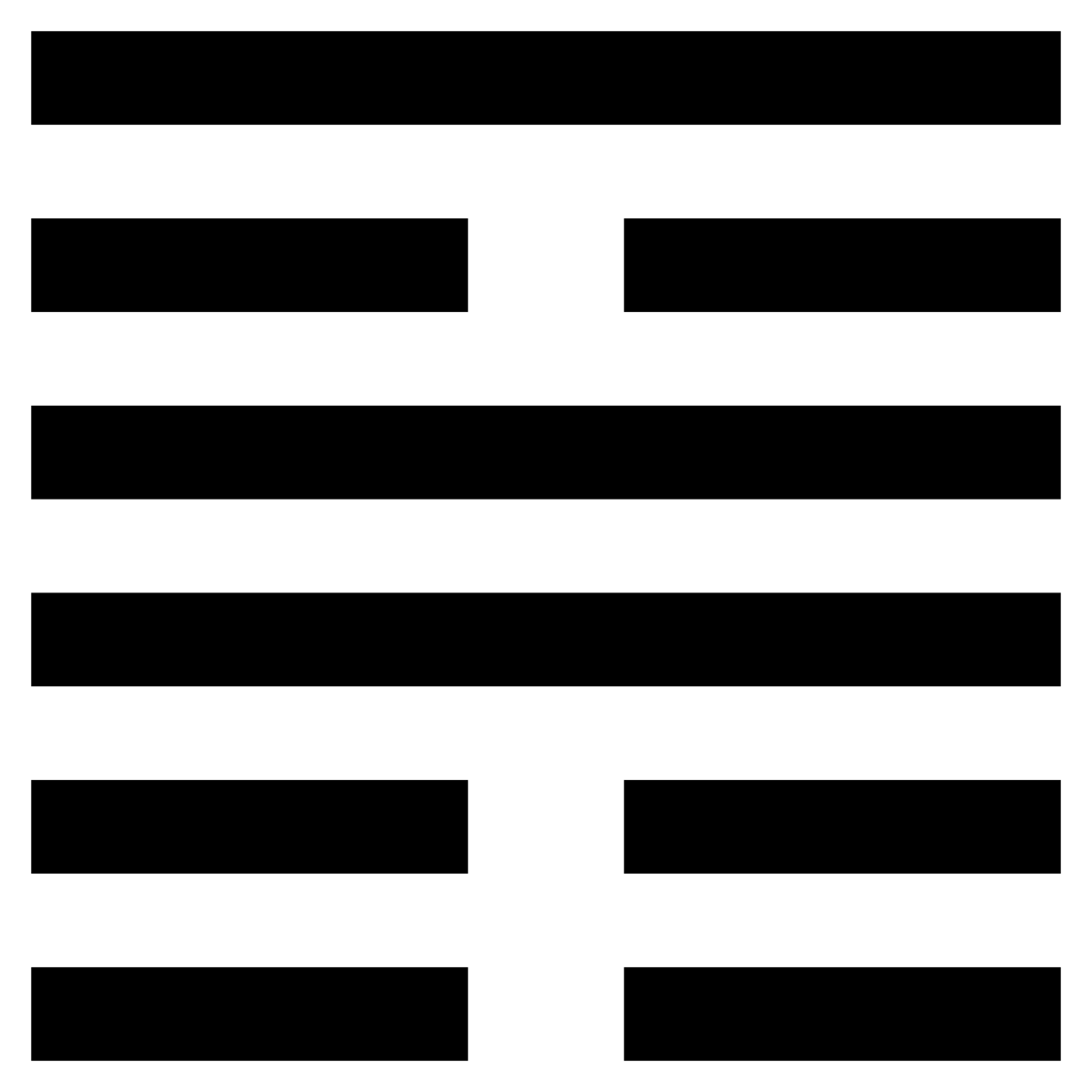

The creation of the I-Ching was a collective effort, as are many wisdom texts and divination tools. The survival of the I-Ching is dependent on its vagueness and ambiguity. I watched this video that says the I-Ching was written by King Wen of Zhou (周文王) in prison. It was intentionally designed to be symbols and hexagrams, and it survived the purge of historical records and scholarly texts by the Emperor of the Qin dynasty (秦始皇的焚书坑儒) because it was seen as a superstitious folk text, not for subversive uses. It was an unreasonable archive.

This series of writings are all unreasonable unarchives, by bilingual or trilingual writers whose tongues are nourished by motherlands, fatherlands, and otherlands with untranslatable poetics. Translated by each author to their respective languages that include simplified Chinese, Japanese, Spanish, Arabic, and French, we are mediating an obscure archive—not illuminating but floating in the spaces lost in translation. We ask the question, how could we communicate with the future so that our predicament would not render meaningless? What is the experience of timelessness in a world that insists on logical and official time?

Chris Zhongtian Yuan responds to the archive of shame and shamelessness with the nourishment of the abstract—on a land they visited as a guest, the same land where we forged our connection and friendship. Alcibíades Elián examines two artists’ fr agmenteda nd accented v oices in “Noting the Throat,” as a way to discuss post-colonial language recovery for descendants of the African Diaspora. In Akiko Ostlund’s “Song of the Sea,” she recounts the experiences of being with three family members who developed dementia at different points of her lifetime, when memories are slippery and the song of the sea holds time more gently. Peng Wu writes a letter to his father in the other world, reflecting on how visa renewal has shaped his art practice, and how to resist being shaped. Romy Lynn and Walid Mohanna collaborate on an epistolary photo essay, in which the work begins with a lost love letter sent from Romy to Walid.

— Xiaolu 晓璐 from Dakota land, specifically Minneapolis