Letter to My Father in the Other World Explaining Four Types of U.S. Visas

How visa and immigration rules shape a life and a career: from art school to job seeking to possible collaborations, and what it means to create with indefinite "temporary" status

To Dad,

A few months after you passed away, I heard from Mother that you asked when my sister and I could go back to the U.S. I know you have been feeling guilty that I left in the middle of my teaching job to come back to be with you and Mother to help with your cancer treatment. I think I know why you have been watching news from TV in bed all the time when you can not get out of bed any more. I think It was about one month from the first COVID case found in Wuhan, and U.S. embassy has stopped in-person visa interviews for which I needed in order to go back to the U.S. Perhaps you wanted to figure out from the news if the COVID situation was getting better so I can go back to the U.S. sooner? You may blame yourself harshly if you know that I was stuck in China for almost two years before I could go back to the U.S. Haven’t we always blamed ourselves, even when we lose in an overwhelmingly unfair fight? But you really shouldn’t. Because I feel these two years were the BEST time in my life. I suddenly recall you told me the same thing, when I asked you how it felt when you were forced to leave your university study and work in a remote poor countryside during the Cultural Revolution. You explained why the years of displacement were the best time of your life. You told me you really enjoyed hard labor work which emptied your mind and made you feel strong and energetic. Over those ten years, you built your own home out of nowhere, with a wife, and two kids. But I suspect this could be selective memories. I remembered you briefly mentioned the brutal and violent political fights you were involved in during your university time before being kicked out. You told us you were naive and said something that got you in big trouble. But you never told us more than that. It must be a hard history to tell and you would rather keep it to yourself. Without my two years of displacement, I would have never had the chance to live and travel with YY—now my husband. Did you know he actually visited me in Shanghai when we were there for your cancer treatment? He wanted to meet you, but I didn’t think it was the best time to come out to you during the most stressful time of our family. Feeling quite frustrated, he still walked me back to the small apartment our family rented nearby the hospital. I crossed the street without him. The gentle evening light shone through the busy traffic of bikes and cars. I looked back and saw him waving his hands saying goodbye across the street. This image etched onto my memory as I realized in that moment, this could be the last chance I could have introduced him to you. And I missed it.

However, I believe I still managed to introduce him to you in the way you taught me. You know what’s the most exciting thing to me on the Chinese New Years Eve? It’s the ritual of bowing in front of the shrines of Grandpa and Grandma, and burning joss paper in the midnight when clock hits 12, as we normally were not allowed to go out this late. But this time of the year you taught us how to fold joss paper into ingots, use chalk to draw a circle with an opening facing the direction where grandparents passed away. Then we burn the folded joss paper in the circle. So they can receive the ingots and our wishes, and they will bless and protect our whole family.

Earlier last year, together with my friends, I started to host a series of participatory art events titled Jin Paper Burning to teach participants printmaking and hand papermaking to create our own wishes and messages artistically. Then we burn the handmade joss paper together to send the wishes and messages to our ancestors—now you are one of them. One of the messages is about the “last chance” I missed. In the block print, I created the image of me and my now-husband on one side of the street; you sit in a wheelchair on the other side of the street. Back then you often used the wheelchair as a support and walked around the neighborhood with us after dinner. It was around after dinner time when we said goodbye to each other. So I was worried you might come across us during your routine walk. Fortunately and unfortunately you didn’t. But now you have received the burned print and you must have understood my thoughts now.

During the two years, I also got to spend a lot of time with Mother after you left. It’s very meaningful to me as I spent so little time with you and Mother since I went to the U.S., and we never question and blame the visa process that makes international travel so hard. I never told you a story of a Chinese woman who worked as the interpreter for an event I co-hosted. I remember she was in her 50s. We were having dinner together after the event. Somehow she started to tell us about how she couldn’t be with her father when he passed away in China. She decided not to travel back to China out of the fear she couldn’t get the visa to come back to the U.S. Telling the story brought tears to her eyes. The regret was still with her after all these years. I didn’t know what to say back then, so I kept quiet. Now I wonder if I should have told her: please don’t blame yourself, you didn’t really have a choice. People always say you have a choice, but I think they just don’t understand. How could they?

Maybe it is her story that made my decision to go back very very easy when I heard you were sick. Maybe I was just lucky: a little before the bad news, I quit my full-time corporate job and switched from H1B work visa to the more flexible O-1 visa that doesn’t constrain a foreign person to only work for a single full-time job. I knew sad stories like that could have happened to me and are still happening to so many H1B holders every day.

Now I have come back to my home in Minneapolis, the city I lived in for ten years. I am sitting on the couch on my front porch looking at the two aspen trees you and mother planted when you visited me. Wind makes the leaves of the aspen shake and make a lovely sound. It makes me feel like telling you a lot of things slower, although this foreign language pushes my tongue with a speed that I feel hard to slow down. I often sound like I have a flight to catch or my home is on fire, especially in front of a group of native English speakers. Because I subconsciously felt I have nothing valuable to say and I want to speak fast or cut it very short so I don’t waste their precious time. And I mumble when I try to speak fast and often they will cut me off and start to talk to one another in an elegant way. When I write in English, it reads like I am doing a TOEFL writing test—using big words I can’t even pronounce to sound smart—that’s what we were taught on how to get higher scores at TOEFL test. Or I write like Immanuel Kant sleep talking. That’s what school made us read. And no one remembered anything the day after. This language makes me feel like I’m constantly being evaluated, judged, and scored.

But somehow my tongue comes back to me when I imagine this writing is a letter to you. You must be very proud I could write you a letter in English of this length. You spent a lot of time studying English after studying Russian in college. Russian became less useful after the relationship between the Chinese regime and the Russian regime went south terribly. When you came to visit me I was so impressed you hand-sewed a brown booklet and made an English dictionary of your own. You cut a few Cub Foods grocery paper bags into rectangular pieces of paper and sewed them together. Without any conceptual artistic consideration, you simply went for the cheapest materials you could get. Do you know you paid thousands of dollars for me to learn how to make handmade artist books at school? You just figured it out yourself. I was even more impressed when I saw the entire notebook was filled with all the English words you wanted to learn, their definitions, as well as how they are used in sentences, etc. With these words you learned, you talked to the cashier at Cub Foods to get back the money that was mistakenly charged, you talked to the neighbor to ask where the lost cat is, you found your way to Aldi for cheaper groceries although you and mom had to walk for an hour.

Before I came back to the U.S., Mother and I worked on clearing up your book cabinets and I found those letters I wrote to you when I was in college. I almost forgot I used to write so much to you—sometimes long letters of four or five pages. Since I haven’t written to you for almost two decades, this letter may get a bit long. I particularly want to tell you more about all the visas I had to apply for. Every time I got a new visa approved, you and Mother were always the first two people I told. As I know you worried about my visa even more than I did. I know it’s been a bit trickier for Mother. As she has never wanted us to live in places far from you. So all the happy news of visa approvals for us could be something a bit harder for her to celebrate. Maybe you were not so approving of us living here either. Once Mother told us, you found a new meaning of the printed painting on the tile in the bathroom—which is a sort of stock image of the view of a harbor where two ships are sailing on the ocean. Those tiles you can find in every household and normally won’t even take a second look. In the painting one of the ships is closer and larger, the other is smaller. In the foreground, you can see the houses and trees on the shore. Mother told us you said this tile graphic was such a prophecy: the bigger ship is our elder daughter who went to study abroad first, and our younger son followed her. The ocean looks so vast and they won’t come back. I heard the story from Mother over video chat and I do remember there is a tile like that. But when I saw the tile in person after I went back to China, I was so surprised. I told mother you were wrong. The two ships are not leaving the shore sailing away. Actually they are returning to the harbor because there are some subtle decorations indicating the front of the ship is actually pointing to the shore. You had presbyopia and perhaps couldn’t see these decorations clearly. Or perhaps you were as sad as Mother about us being so far away. It’s just that you believed our American Dreams are more important.

Temporary for a Decade

I received the notice of the approval of my fifth visa for temporary foreign workers on January 26, 2022—in the eleventh year of coming to live in Minnesota, the United States. Over the past decade my mind has been busy every day battling for the right to live in this place. I haven’t got time to contemplate what it means to live in a place temporarily for a decade. I am grateful to my dear friend Xiaolu Wang for inviting me to write this article. This opportunity allows me to retreat from the battle, lay down and breathe to gain clarity around what I have been through. And eventually I got the idea of writing this letter. However, right after this rare and restful break, I will enter the most difficult battle, to end this entire battle for myself—my green card application.

It feels like a continuous battle stretching over a decade. But it’s not a lone battle. It’s a battle with a community of friends, colleagues, and allies here. It’s them who keep me here with the opportunities and friendship, and brought me back here even though I was not allowed to come back for two years due to my visa issue and the pandemic.

More importantly, I imagine someone who is just about to start a long journey like this comes across this writing, this letter can be a small lamp lighting the way. So this letter is not only to you, my father, but also to foreign artists like me who have fathers far away in other different countries. This writing reflects on how my own art practice has been so profoundly shaped by a giant, old, and non-art institution: the USCIS, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. An institution that has been rarely discussed in the context of institutional critique. Being aware of its dangerous shaping force, we can resist being shaped in such a vulnerable way. My decades-long dancing with this overwhelmingly non-negotiable force actually reminded me of the practice of tai chi push hands you taught me. One day when I was a kid you said, let’s play a simple game. We stood in an interesting way facing each other. We kept the back of our right hand in touch. One person can push in any direction or yield to any direction as long as the hands keep in touch. The person who eventually loses balance and moves the foot loses the game. Of course I lost all the time and cried hard. You started to show me the trick: you told me when I am facing a force that’s much stronger, like your strong pushing hand, I shouldn’t fist-to-fist push back directly, as I could be knocked over immediately. I should keep my hand yielding to the strong push but never retreat completely. My hand should keep in contact with your hand, so I can sense the changes of the force. The truth is even the strongest force often doesn’t last long. When I sense the weakening of your hand I should push the hand sideways to unstabilize your stance. After some practice, a kid like me sometimes can make you stagger.

I believe when we can have a good awareness of the “pushing hand” of the visa, we can avoid being knocked over, pushed around, and turn the force into a source of artistic strength. So here we go, my many visa stories that I have never told you.

Evergreen 常青

I started my life in the U.S. as an art student, an unusual kind: the kind of student who cannot sell artwork, can not take commissions, or gig jobs—as USCIS makes it illegal for student visa holders like me to work, which includes all the above scenarios. I spent the whole two years making things without knowing who I am making these things for, who may want to buy it, not to mention a career path. And somehow that’s what fine art is supposed to be —making things for yourself. It makes perfect sense when art schools were for rich families to send their daughters to be artistic to marry with a rich husband. It makes good sense for students who have their tuition paid with trust funds to explore themselves and enjoy the creative experience. It makes no sense for someone like me using my own years’ savings plus my parents’ decades’ saving to learn how to make things just for myself. But strangely I did anyway. And I did it pretty well and enjoyed it very much. Why? I still can’t explain after all these years but I remember how it felt. It felt like you are one of the chosen few to be accepted by this cult and you are making noble sacrifices of your life to earn a place in this cult. In retrospect, I was thoroughly disconnected from what was going on outside the cult—in this country, in this city, in the neighborhood of the school where I lived. We were locked in our “studios” pondering the philosophical questions of aesthetics and existential questions of who we are. Meanwhile, student visa restrictions enhanced this disconnection by forbidding the most effective way for a newcomer to connect with the society: work.

After you selflessly paid my tuition with your and Mother’s decade of savings, you came to visit me all the way from China and stayed with me for four and a half months with the curiosity of what I was learning. That was your first time visiting this country. Not surprising at all, you seemed to get in deep worry with what you saw. I don’t know if you still remember you participated in a performance/sculpture piece of mine titled Evergreen, involving you, Mother, and I taking a long walk in a certain way. Involving you and Mother into my artwork was encouraged by my mentor Piotr Szyhalski back then, because I talked to him about how hard it is to explain my work to you. Along the walk when the traffic light was green, we walked forward. When we came across red lights, we turned right and kept walking without stopping. In this way, red lights couldn’t stop us as if the traffic lights were forever green. I couldn’t explain what the activity was about back then. Now I think maybe practicing Evergreen can make a person more comfortable with being non-purposeful, flexible, thus unstoppable? Perhaps. Better if you have food in your belly. So we also carried a Cub Foods grocery paper bag with some bananas in it. I used a pencil to draw the path of the walk on the bag as a very spontaneously unplanned documentation of the performance. We went home around sunset when the bananas were finished. The paperbag with my drawing outside and the banana peels inside was placed near the gallery wall on the ground for a student group show. What I didn’t tell you is when I went to the opening, somewhat with pride, I found the grocery paper bag was missing. It became a bit cliche art school joke being told again and again over drinks with old art school pals. Now when retelling it to you, I found it is such a perfect metaphor for my life in the U.S.—as long as I am willing to change my route, nothing can stop me from keeping going, not the traffic lights, not the visa. Though the pain of being forced to change route comes a bit later.

A Non-Resident Alien

In the last semester when we were about to get kicked out of the “cult,” all of us were in somewhat panic mode. The clock of getting kicked out of the country was really ticking. Everyday I was stressed by the question of how I could get a job and an employer-sponsored working visa. Back then nobody in the school knew of the existence of the O-1 visa which is a more suitable visa type for artists. It reflects how little the school actually cared about the success of international students back in 2013.

Like a cat drowning in water, me and another friend of mine decided to do everything we could to get a job. We thought of the major that sounds most promising: graphic design. We started to force ourselves to go audit graphic design classes together. It felt like we formed a two-person support group for quitting-art rehabilitation. We redid our entire portfolio websites—removing all the fine art-looking works and loading up all the commercial-looking design works—rushed out overnight, logo design, UI design, etc. After the complete makeover no one can even recognize me by looking at my website. And it is fascinating to see the same shit happened to the websites of my classmates. I was like, oh, you are “enlightened” too! It sounds funny now but it felt no less painful than conversion therapy at the moment. However being forced out of the so-called fine art world made me see it from outside. Looking back from today, after being a designer for many years, many artworks look very much like failed visual communications. On the other hand, many design works make too much sense, and leave little space for the mind to wonder.

The process of my job search showed how ignorant I was about my identity and this country. I just kept sending resumes crazily, which is the way I used to find jobs in large cities in China. I had no idea there might be few companies in a small city—like Minneapolis—that will give a design job to someone who has no previous work experience in the U.S. Because in the industry of graphic design, outside the first-tier large cities like New York, it is still an industry dominated by white Americans. Back at the time I was looking for my first job, design firms didn’t even have to pretend they needed diversity. I am not sure how much has changed over the past ten years.

Because of the intentionally-made-complicated visa procedures, these companies are reluctant to consider job seekers like us because they have no experience in applying for work visas for foreign employees. While on the opposite, companies in the more diverse first-tier cities have tasted the profit of hiring foreigner workers. From the conversations with my friends who got jobs in those cities, I learned that many Asian immigrant employees are recruited because they expect you to work overtime like a mule. The boss knows that the intentionally-made-complicated visa procedures make it very difficult for foreign employees to change jobs. And once you leave the job, you lose your visa, and become illegal. Many companies that like to hire immigrant workers will give you a lot lower wages and fewer raises in exchange for getting a visa for you. A single employer-petitioned H1B work visa sometimes feels like fishing bait to exploit foreign workers.

Even worse, visas can be weaponized by some companies. An older friend told me a story about her job search back in the 90s. She had a job at the time but she got an offer with a higher pay from another company. So she communicated her plan to resign from her current employer. The current employer surprisingly offered to give her a promotion, matching her salary to the same amount offered by the other employer, in order to keep her. Considering the trouble of changing jobs and visas, she accepted the current company’s retention. Soon after that, the company hired a new assistant for her to train. My friend didn’t think too much about it and trained the assistant in all the skills needed to do the job. But soon after the assistant was able to work independently, the company fired her without warning. The company fired her on account of “no resources for new employees”, even though they just hired that assistant and let her stay. That person was Chinese as well. The compay seemed to strategically pit them against each other and demonstrate how replaceable they are. She immediately lost her job and her legal work visa. This well-planned attack hurt her tremendously. She lost a lot of agency to effectively shape her future career and life. It is still an unforgettable trauma even today, decades later.

Navigating the job market of this small Midwest city taught me a lot: referral is probably the most effective way to find a job. Here, each profession is like a small community, and people tend to hire someone they know, more or less. If you can get a referral, it greatly increases the chances of getting a job. Many people I know have their first jobs through friend referrals, including myself. Looking back now, the first job in this country was often the hardest step, and it feels much easier after that.

Skin color and race is something well-discussed in this country when it comes to job hunting. For foreigners like me, I was even more insecure about my accent. I still remember the time right after graduation, I rarely got the chance of in-person interviews after many phone interviews. It wasn’t hard to imagine why. But now I believe that there are as many people who laugh at you as there are people who are willing to help you. Maybe when they hear your accent, they may recall—once upon a time their accent exposed them as an outsider. Later, when I applied for the O-1 visa, I hoped to get a recommendation letter from the design director of 3M, but we only met once. He wrote me a very detailed letter of support, and told me that he was also an immigrant and needed a lot of complicated visas back then. It seems all we need to do is to identify those who are really willing to help us, and ask clearly and loudly for help. There are more people who are willing to help than I initially thought.

When I finally got my first job, I started to experience the exceptionally unique tax filing process in the U.S. I found that the category of people like us in the government’s official tax return documents is actually called “non-resident alien.” Sounds like a Hollywood science fiction movie. I searched for this term, and the top search result turned out to be a recent hit science fiction comedy titled Resident Alien. The overall storyline is that an alien spacecraft crashed in a small American town. In order to blend into human society, the alien pretended to be a human (unsurprisingly a white male), but his behavior was weird and he didn’t understand social common sense at all. The secret mission of the alien is to kill all humans. This reminds me of what I once told the boss of my company that I wanted to use the education funds from the employee benefits of my position to go to the University of Minnesota for a course to correct my foreign accent. Because what I was distressed about at that time was a white male colleague who didn’t really understand graphic design was presenting my graphic design drafts for me. At that time, I was naive to think that by correcting my accent and speaking an authentic Midwestern American accent, I could perfectly assimilate and be respected. Now it seems that the series of efforts of the ineffective “disguise” to try to integrate into the company are very similar to the plot of this sci-fi comedy. After briefly decorating the company’s diversity report, the company refused to sponsor me for a green card. This dead end has wasted me more than four years.

我们想到了我们艺术学校里最实用的专业:平面设计。硬着头皮我们开始旁听平面设计的课程,一边改简历投实习职位一边重新设计网站,把之前做的各种”纯艺术“画风的作品撤下,换上各种讨好设计公司风格匆匆赶出来的logo,UI作品。 瞬间作品网站像换个了人,亲妈也不认得的makeup。画风好像各种美国企业和机构标榜自己多元文化而花十几块钱买的stock photo一样假。回想起来打定主意进行这般落水猫咪应激的迅速改头换面涂脂抹粉带来的心理创伤简直不亚于性扭转治疗。我想如果不是一直以来处于脱离现实的学校教育状态,重新进入现实的学习痛感应该不至于那么强烈。正如最近朋友推荐给我的一本书的名字”The Way Out is In”《离开是一种进入》。作者是一位很妙的越南禅宗大师Thich Nhat Hanh. 离开让我不舍的学院“纯艺术”世界正是进入另一种新的艺术世界,现在看可能是进入一种更relevant的艺术世界。

找工作的过程也显示了我对自己的身份和这个国家有多么无知。我们只是按以前在国内找工作的方式,疯狂的投简历。完全不知道在美国非一线大城市没有多少公司会把设计工作职位给一个之前在美国没有任何工作经验的人。因为在平面设计这种行业,非一线大城市之外,依旧是一个白人本国人占绝对主导的行业。前几年设计公司甚至不用假装他们需要多元化。这些公司因为没有替外籍员工办工作签证的经验,而因为办签证手续复杂而不愿考虑我们这样的求职者。而最多元的一线城市设计公司,比如纽约,亚裔移民员工被招进去很多是期待你像牛马一样拼命加班。因为老板知道你一旦离职就会失去合法居留的签证。很多喜欢雇佣移民员工的公司会通过帮你办签证作为交换而给你更低的工资,更少的涨薪。由单一雇主支持的H1B工作签证有时候感觉像一种奴役和剥削外籍工作者的带着诱饵的枷锁,难以挣脱。而且有的公司还会将签证“武器化”。有一位年长的朋友跟我说过她当年的一个职场故事。她当时幸运的得到了一个新工作的offer,有着更高的报酬,更好的发展前景。于是她就跟当时的雇主表达了离职的计划。而当时的雇主却意外的表示愿意给她升职,把她的薪水增加到另一个雇主offer同样的数额,以此留下她。这个朋友考虑到换工作签证的繁琐流程就接受了当时公司的挽留。之后这个公司还给她新雇了一个助手,让助手跟着她学习。这个朋友也没有考虑太多,教了这个助手所有工作上的技能。然而不久以后当这个助手开始能够独立工作以后,公司将她毫无预兆的解雇了。她立刻失去了工作也失去了合法工作签证。这件精心预谋的攻击让她在人生中失去了很多把握自己命运的主动权,即使在几十年以后的今天依然是一处难以忘却的创伤。

另外我感受到的在双子城这样的中部小城市的一个很有趣的文化现象:熟人推荐是找工作最有效的途径。在这里,每个行业像是一个不大的小社群,大家倾向于雇佣多少有些关系的人。如果有熟人推荐,会让得到工作的机会大大增加。我所知道的许多人的第一份工作都是通过朋友推荐,包括我自己。现在回头看,在这个国家的第一份工作常常是最艰难的一步,之后会感觉越来越顺利。另外,我知道你也许在无数的面试中为面试官难以掩饰的对你不流畅的英语和浓重的口音所窘迫,甚至自己都不相信自己值得这职位。但请你相信有多少嘲笑你的人,也有同样多的愿意帮助你的人,也许他们听到你的口音会想起自己刚刚来到这个国家时的自己。我后来在申请O-1签证的时候,希望可以得到3M的设计总监的推荐信,但我们其实只有一面之缘。他却给我写了一封很详尽的推荐信,并跟我说,他也是一个移民,当年也需要很多繁琐的签证。所以你需要做的是,就是辨认出那些真正的愿意帮你的人,清晰明确的说出你需要帮助。你会发现愿意帮助你的人可能比你想象的多。

当我终于得到第一份工作,开始更多的体验可怕的报税手续。我发现在政府的官方报税文件中对我们这样的人的称谓居然叫做“外星宿主Resident Alien”。听起来像是好莱坞的科幻电影。我搜索了一下这个名词,最靠前的搜索结果居然是最近一个热播的同名科幻喜剧。大致内容是一个外星人飞船坠毁在一个美国小镇,外星人为了融入人类社会乔装打扮变成人类(not surprised白人男性)的长相,但是举止怪异完全不懂社会常识。外星人的秘密任务是杀死全部人类。这让我联想到我曾经跟我公司的老板说我希望可以用我工作职位附带的福利教育经费去明大上一个纠正我外语口音的课程。因为当时我所苦恼的事情是为什么当时公司的设计方案讨论会议上,并不是由我来陈述我的设计方案,而是由一个并不懂设计的白人男性同事。当时居然天真的以为通过纠正我的口音,说一口正宗的美国中西部腔就能让我完美的assimilate融入和被接受。现在看来十足蹩脚的“乔装打扮”尝试融入公司的一系列努力像极了这个科幻喜剧片的情节。在短暂装点了公司的多元化门面之后,公司委婉拒绝了帮我办绿卡的要求。这条死胡同让我走了4年多的时间。

Dad, now I am an “individual with extraordinary ability and achievement!”

Since the company refused to help me apply for a green card, I started goofing off at work. Meanwhile I started to use my spare time to make art again. Often caught in nostalgia for my hometown and not seeing a future for my career here, I began to constantly doubt my decision of staying in the United States. With such doubts, I wondered what my other immigrant friends thought. So in 2017 I started a small side art project called CarryOn Homes with my photographer friend Shunjie Yong, who had the same doubt. We started interviewing and photographing immigrant friends we knew. We talked to them a lot during the photo sessions about the reasons why they came to Minnesota, and what made them decide to settle here temporarily or longer. The topic also touched on a lot of the various painful decisions they made when faced with difficult visa applications. And then two more artists we interviewed and photographed—Aki Shibata and Zoe Cinel—also joined the artist collective we later founded with the same name, CarryOn Homes. With the same experience of confrontation with visas, it was easier for us to form close alliances. Looking back at this process now, in the face of the overwhelmingly powerful “push-hand” like a visa, I had to yield first to find a way to stay standing, looking for an opportunity to turn this pressure into a kind of motivation for resistance.

Another important project that helped me to get a visa also came indirectly from the visa application: with the meaninglessness of work, and the anxiety and stress caused by teamwork, I found that I fell into frequent insomnia, sometimes unable to fall into sleep through the whole night. The funny thing is that I often watch my favorite childhood horror movie, Alien, when I have insomnia, which distracts me from project pressure and visa anxiety. In a meeting with Boris Oicherman, a curator at the Weisman Art Museum (WAM), I proposed to work on a “sleep art project” for my residency at WAM. With the support of Boris, I started to collaborate with UMN School of Medicine to study the science and cultures of sleep disorders and insomnia.

These art projectswould not have been initiated without the visa difficulties, which somehow got transformed into a force that helped solve these difficulties. Because of these projects, I received many museum exhibitions and media coverage, which made me lucky enough to receive a visa with more freedom, the O-1 visa.

According to the official definition of the O-1 visa, an O-1 is a work and residence permit for “individuals with extraordinary ability or achievement.” USCIS considers these factors when deciding whether to approve an artist’s O-1 visa application: media coverage of the artist, the level of exhibitions the artist participates in, and whether they have won an art fund or design competition award. These metrics often force the artist to be a fame-seeker. You have to go around and meet powerful people in the industry, because their letters of recommendation will determine whether or not immigration will approve your visa application. This makes it very disadvantageous for introverted people who only know how to focus on artmaking. Here is a quote from immigrant artist Roshan Ganu: “I took all my shame, packed it in a box, and threw it into the basement. Then I start to ask everyone, please give me an interview and write about my work. As I really need it!” Without letting go of shame and looking around for media coverage, it’s hard for a foreign artist who just graduated to get approved for an O-1 visa application. Also for the visa, I feel that when working with art institutions, I will be in a more unequal position of power. Because in the opinion of the Immigration Service, large art institutions are more able to prove an artist’s “outstanding ability and achievements.” In this way, you sometimes have to give up more of the artist’s autonomy and accept unfair pay in order to get exhibition opportunities with art institutions.

Another more overlooked visa impact is that it has made me become a more self-centered person. The immigration office measures whether the individual applicant has outstanding ability and whether the individual has achieved outstanding achievements. Such judgment logic may come from the value of individualism in the West. It implicitly denies the value of collaboration-centered artists like myself. I had to care so much if my name was featured more prominently in media articles, as it increases my chances of getting a visa approved. During many public presentations I started to realize that I talked too much about my own contributions. This created a lot of tension between me and my collaborators.

After I finally got my O-1 visa approved, and quit my corporate job, I thought I would be finally able to fully focus on my artist career. Later in that year, you told me you got diagnosed with late-stage cancer. And you kept it a secret for a while. I think you didn’t want to tell me, as you knew it was not easy for me to get the teaching job and didn’t want me to leave the job for you. Eventually you decided to travel to Shanghai to explore potential treatments. That’s the moment when you decided to ask me to come back to help. I am glad you did ask and I am glad I got to be with you and family for this hardest time.

自从公司拒绝了帮助我申请绿卡以后,我就开始了打工人的躺平划水摸鱼生涯,并开始用工作之余的时间重新开始艺术创作。在对家乡的思念和异国工作前景暗淡的状态下,让我开始持续的怀疑自己留在美国的决定。在这样的怀疑里,我想知道自己的移民朋友都是什么样的想法。于是在2017年我和有着同样疑问的摄影师朋友Shunjie Yong开始了一个叫做CarryOn Homes的自发艺术项目。我们开始采访拍摄自己认识的移民朋友。和他们聊了许多他们来到明尼苏达这里的起因,过程,以及让他们决定在这里暂时或者更长期的安家落户的原因。话题也涉及了很多他们面对艰难的签证申请时,做出的各种各样的痛苦的决定。而之后两个我们采访和拍摄的对象/同是移民的艺术家Zoe Cinel和Aki Shibata也加入到这个项目的创作中。在这样一种对抗签证的过程中,大家更容易的结成了容易亲近的盟友关系。现在回看这个过程,在面对签证这样一直势不可挡的“推手”逼迫下,我不得不先退而求其次(yield)先寻找一个留下来的办法,在找机会把这种逼迫转化为一种反抗的动力。

另一个帮助我的到签证最重要的项目也间接来自于签证申请,工作无意义,和团队合作引起的焦虑和压力。我发现我陷入了频繁的失眠,经常彻夜都无法入睡。而好笑的是我在失眠的时候会经常看童年时最爱的恐怖片《Alien》,让我分散来自项目压力和签证的焦虑。在这个阶段我遇到了Weisman Art Museum (WAM)工作的Boris Oicherman,在WAM的residency的项目中,我开始和UMN医学院的合作,研究睡眠和失眠相关的科学和文化现象对策。

这些如果不是签证困难就不会发起的艺术项目最后成为了帮助我自己和项目里其他移民艺术家解决签证问题的力量。因为这个项目后来获得了许多美术馆的展出和媒体报道。而这些展出和报道让我得以幸运的申请到一种更自由的工作签证O-1签证。

根据O-1 签证的官方定义,O-1是提供给“拥有杰出能力和成就的个人Individuals with Extraordinary Ability or Achievement”的工作和居留许可。移民局USCIS在判断是否批准一个艺术家O-1签证申请主要考量这些因素:媒体对艺术家的报道,艺术家参加展览的规格和数量,是否获得艺术基金或者设计竞赛的奖项。 这些衡量标准常常会迫使艺术家成为一个急功近利,追逐名声的人。你不得不到处逢迎,认识行内的有权势的人,因为他们的推荐信会决定移民局是否批准你的签证申请。这样让性格内向懂得专注于艺术创作的人非常不利。这里可以引用一句移民艺术家Roshan Ganu的原话:“I took all my shame, packed them in a box, and throw them into basement. Then I start to ask everyone, please give me an interview and write about my work. As I really need it!” 如果不放下羞耻心到处寻找媒体报道,一个刚刚毕业没多久的外籍艺术家很难得到O-1签证申请的批准。同样为了签证,我感觉在和艺术机构合作的时候,会处在更加权力不平等的位置。因为在移民局看来大艺术机构更能证明一个艺术家的“杰出能力和成就”。这样你为了得到和艺术机构的合作和展览机会,有时候会不得不让渡更多的艺术家的自主权。另一个更容易被忽视的签证影响是让我感觉变成一个更自我为中心的人。 因为移民局是对申请人个体是否拥有杰出能力和个体是否取得杰出成就进行衡量。这样的判断逻辑可能来自于西方对于个人主义价值的崇尚。这样的判断标准会对艺术家,尤其是像我这样的以团队合作为主的艺术家产生难以抗拒的负面影响。我会更希望自己的名字在媒体文章中被放在更显要的位置,因为这样可以增加我获得签证批准的可能性。我有时候会意识到在公开场合更多的谈论自己的贡献。这样团队里合作的其他移民艺术家之间产生竞争和对立的关系,而不是至关重要的互相合作和支持的关系。

We need to get married next week

After one and half years living in China, I was offered a full-time teaching job in Minnesota. Mother was relieved. Before that, neither me nor my sister had a real job. We were okay financially, as we Asians are famous for being good at saving. And back in school I was known as the “king of cheap fun.” So being unemployed for two years wasn’t as deadly as it sounds. But still, Mom felt so relieved and stopped feeling guilty, and worried much less. That offer was the best news our family got in the past two years. We even started to routinely go out for hotpot dinner. :p

After loads of paperwork working with the school lawyer and great support from my collaborator from the UMN medical school, I finally got this unusual type of visa in the category of NIE (National Interest Exception.) With this visa I didn’t have to stay in the third country outside the U.S. for two weeks required by the U.S. pandemic travel policy. However, to keep the cost low, I still had to book flight tickets with multiple stops. In the fire and smoke of COVID pandemic, traveling like that made me feel like a rat running under the debris of bombs from one safe zone to another. Though the social media posts got me likes…

YY bravely decided to come to visit me shortly after I left. We have gotten to a point where we both know we don’t want to live separately. He had to follow the U.S. travel policy of two weeks’ third country quarantine before he could cross the U.S. border. So he decided to stay with his friend in Istanbul for two weeks. He sent loads of street cat videos and we dreamt someday we may live there and would have a lot of street cat friends. He came with a tourist visa and planned to go back to China at the end of the six-month visa period. When the end of the six-month period approached, he started to research the flight back to China. We found the flight ticket from the U.S. to China went sky high. We realize the COVID omicron situation in China got very bad and China posted an unprecedentedly strict nationwide lockdown including domestic and international travel restrictions. On the other hand, we loved our shared living very much, even in the coldest winter. One day we decided to walk on the frozen lake Bde Maka Ska. Though it was windy and cold, he got so excited and started to roll on the frozen lake and made snow angels. After we got home he realized his phone was gone. And later we found out that very hardworking phone sent the last photo he took on the frozen lake to the cloud before it turned off due to the extreme low temperature. And the precious photo was me taking a leak on the lake.

Anyway, it was an easy decision for us to just get married so he didn’t have to take the dangerous and expensive trip back to China. If same-sex marriage in China were possible we could have gotten married in China so he could come to the U.S. as my spouse. But I don’t see that happening in my lifetime… We needed to get married really soon, as the date of his status becoming illegal is approaching soon. It was very stressful to get married in such a short time. We even talked about whether we needed to go to Las Vegas to get married where it’s known for a fast and simple marriage process. We got into a few fights and had several nights of bad sleep. I remember we were sitting in our car outside the DMV at Midtown Global Market making phone calls to the judges listed on the marriage license. We looked through the list and started to call female-like names with strange last names. We wanted to get married by a woman of color judge. Finally the assistant of a judge answered the phone. He spoke English incredibly fast and I had to ask him to repeat the questions multiple times. But finally we scheduled the ceremony at the city court the following week, though both of our names got spelled wrong in the appointment. I had to email them to correct them. We didn’t like the default Christian vows attached in the appointment email. So we wrote our own vows in two days and sent them to the judge via email. However the judge still read her default vows first and added the vows we wrote in the end. The vow-reading got so long that the smile on our faces started to freeze. But it still matters so much to us that we can legally get married here.

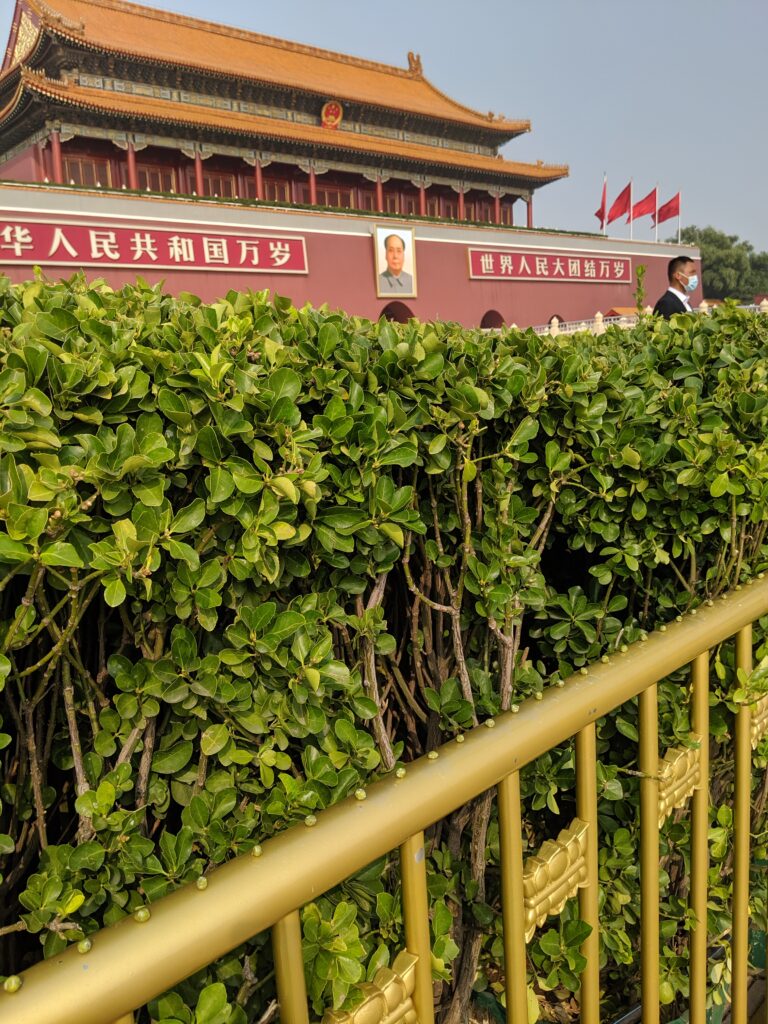

Do you still remember the yard sign you saw when you and mother visited me in 2012? It is a yard sign with big orange text: “Vote No.” They were everywhere around the apartment where we lived. You asked what it means. I was nervous and lied immediately, “I am not sure.” For a millisecond I wanted to tell you that it’s people here fighting for the rights of same-sex marriage and they won. But I missed the chance of sharing the joyful victory of people of my kind, like I missed the last chance introducing my now-husband to you. Though all victories are impermanent, as Buddha taught us. Recently the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Roe v. Wade case, which means there will be no nationwide protection of abortion rights. Using the same reasoning, they can take away the rights of same-sex marriage, birth control, and many more. Without legal same-sex marriage, I fear my husband will be forced to leave this country where we are building a home. Mother and you always told us not to talk about politics. I know why you, Mother, Uncle, Aunt, and many, many Chinese elderly people said that because of what you all have been through: Cultural Revolution, One Child Policy, 1989 Tiananmen Square protest and massacre…

These are the regime’s bloody crackdowns that shaped you and your generation’s deep fear of being involved in politics. And through you these events shaped me too. I learned to yield in front of power. I fled away from China when homosexuality is a shame and social taboo. Can you imagine holding the hand of your loved one while walking on the street can be a social and political action? Yes, it is to me. I held the hand of my loved one on the streets of my hometown, Beijing, and my neighborhood in Minneapolis. I remember the very different comfort levels of holding hands in these different places. I felt most comfortable in my neighborhood in Minneapolis (but only during the night.) I also remember where I wanted to hold his hand but I decided not to—today in St. Cloud—a city about one hour and half drive from Minneapolis where I teach. Because I read there was a gun shooting a block away from the university campus a couple of days ago in broad daylight. How interesting that holding hands while walking on the street can be such a device to measure the political atmosphere of a place. You see, this is how all the political events affect the everyday life of people like me.

This letter is taking a week to write, but I just started to feel there is so much more I can tell you. But I have to get back to the next hard visa fight. Hopefully I can write you more afterwards. I will send this letter as usual during the next Jin Paper Burning event.