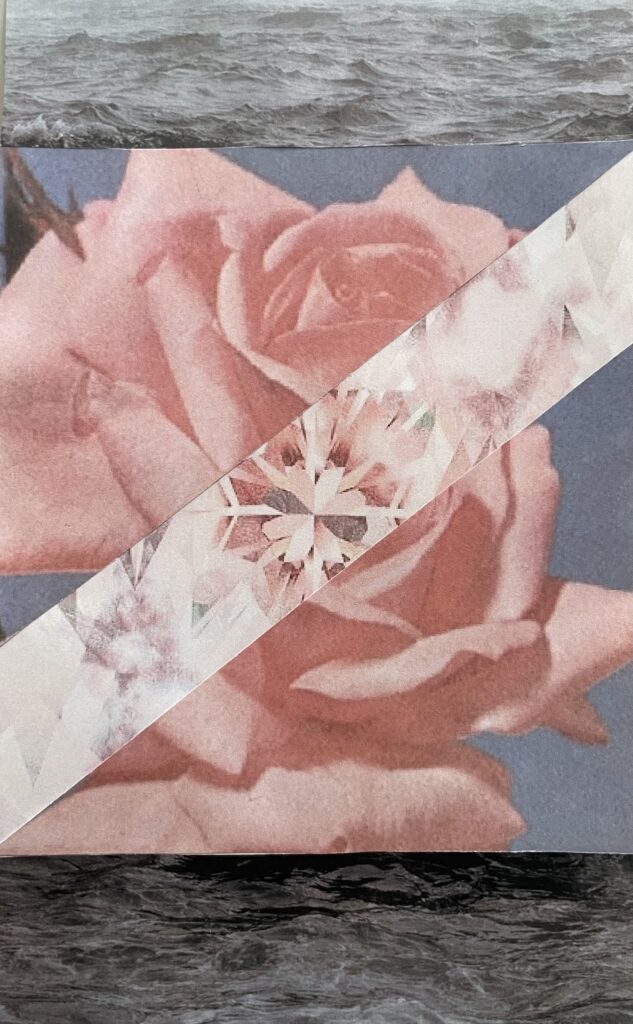

Song of the Sea/うみのうた

Four stories on the horizon of loss: the slipping of memory, family, and place, across bodies of water and expanses of time

My name is Akiko. I am a multimedia storyteller.

A few months ago I got a text from my dear friend Xiaolu. She asked if I wanted to write a little essay about time. I replied, “Yah, okay,” while watching Atlanta, eating popcorn, brewing coffee, browsing a summer dress on anthropologie.com, moisturizing my legs, taking off my socks, thinking about haircuts, and nothing about what I would, or could, write.

But here it is: my first essay.

My father’s mother

We were out for several hours.

We left right after breakfast for what was supposed to be a casual morning walk. Now the cool, early morning air has been replaced with the smoggy, dirty breath of the big city. The August sun was on top of us, baking my head covered with thick black hair.

At one point, I realized we were on the wrong side of the highway, and I knew it meant we were outside of our city.

Other than that, I didn’t know where we were. I didn’t know how to get us back home.

I was nine, and I was with my grandma.

The fact that I was with her made the situation much worse than if I were alone.

My grandma led the way without turning around. I asked her a few times if we could stop at the payphone just for a moment so I could call my mom, but Grandma didn’t answer.

I don’t know how my parents thought it would be a good idea to let my grandma go for a walk with a nine-year-old as a chaperone. Or maybe they didn’t. They were a decade younger than I am now, raising two young children, running their business, dealing with my dad’s addiction, and now taking care of Grandma.

My grandma arrived earlier that week. She had lived with my uncle and aunt on Kyushu island for years, but her dementia had gotten worse to the point where they could no longer take care of her at their home. That was why she had come to live with us in Osaka.

We picked her up at the airport. She was a skinny, thin-haired, old woman with soft, smiley eyes. Never leaving Kyushu, the southern island, for her entire life, she had the face of a fisherman with deep wrinkles running on dark, brittle skin.

On the way home, she got carsick. But she didn’t tell anyone and kept swallowing her vomit until my dad noticed and scolded her, like he was the parent now.

She grew up during World War II, married my grandfather, and raised four boys in post-war poverty. They had to give up the youngest one for adoption when he was four. My dad secretly took his high school exam and passed, but he knew the family couldn’t afford it, so he kept it to himself, and started working right after he graduated from middle school.

The area we were wandering was a busy, industrial part of Osaka, crowded with small screw factories and welding shops under crisscrossed highways. There was constant machine noise, and the air always tasted metallic. I followed my grandma’s bony back, wondering how to get help from grownups.

Shortly after we passed some smoking men and a yellow Komatsu forklift backing out of the warehouse entrance, we abruptly came into a tiny patch of residential area. Grandma walked right into one of the houses. As if she did it every day, she smoothly unlocked and opened the black steel gate.

How did she do that when she couldn’t even remember her name or her son’s face? My dad said she was always good with her hands. I tried to picture her in a different place, at a different time—maybe in her twenties, living in the shack by the sea, busy cooking, mending, and making things happen for her children somehow. Does that person still live in her?

As grandma kept trespassing in the yard, I desperately tried to get her out of there before something terrible happened. Suddenly—a dog showed up growling, and barked at Grandma furiously. I knew it wasn’t the kind of bark people would say, “Oh, he just does that, you’re fine.”

The dog was not just doing that, and we were not fine.

In no time, there would be lots of blood and screams, followed by an emergency room visit and a long talk at the police station.

I saw the dog about to jump, and clenched my jaw. Grandma, though, took one step in and raised her hand. She put it above the dog’s head, like Jesus healing a sick person.

“There,” she said to the dog. Oddy, he stepped back.

She mumbled something stern but incoherent to him. He looked down and fell silent.

I once read that dogs can smell fear. Can they smell embarrassment too? Do they feel embarrassed and uncomfortable when they see something sad? He left us alone until Grandma was satisfied and ready to leave his owner’s garden.

She was always so sure about her choices. But I only knew her with dementia.

Living with her was exhausting. After a month of living with her, I was already sick of her asking when she could eat, and when I would leave. “It’s getting late. Why is she still here? Where are the parents?” she would ask my mom. That always did it. It was hard enough to compete with my cute toddler brother for Mom’s attention, and now my grandma was here, being ten times needier than us kids and our alcoholic dad put together. I felt like my mom would forget I existed if I didn’t make any noise for five minutes. Where are my parents? Why am I still here? Doesn’t she think I ask myself that every night? With blinding rage, I would scream at the top of my lungs, telling her how her brain was rotten and no one wanted her, until I was sent to my room.

She passed away in an assisted living home in Kyushu several years later.

I remember it was December 1, but I can’t remember her name now.

I wish I wasn’t nine then. I wish it had been different.

My mother’s mother

The last time I saw her was right before I left the country.

I visited her with my fiancé on the way back from the embassy in Tokyo.

She looked up at my fiancé standing in the entranceway. With a soft smile she bowed and guided him in, her tiny feet shuffling under her apron.

I told her we were going to get married this summer and I would live in America for good.

“For good.” She nodded several times, as if she was chewing those words.

She was hard to read. On the surface, she seemed to accept whatever was presented to her, as is—a lemon is a lemon, a dolphin is a dolphin, a granddaughter who leaves the country with an American man is just that —things are neither good nor bad, sad nor happy.

My mom arrived a few hours later from Osaka and we had lunch together.

“COME, COME, WELCOME!” my grandma yelled abruptly as she served us tea after lunch.

She told my fiancé that was the only English phrase she knew.

We burst out laughing and asked what TV show she had been watching.

She told us she used to say it when she was working at the black market right after the war.

“You worked at a black market?” my mom asked, surprised. “What were you selling?”

“Oh, stuff,” she answered, as if she were too lazy to get into details.

I tried to picture it, but immediately realized I didn’t have any visual elements to materialize the scene in my mind. What is a black market anyway? How old was Grandma, and how did she look then? Did America ever come and drop bombs in a tiny city like this too?

My thoughts hit a dead end. I stared at the bitter matcha dust slowly settling at the bottom of my teacup.

On the day we left her house, she gave me some of her kimonos. She had kept them for more than 50 years, but when my mom mentioned I quilted, she decided to give them to me.

She picked up one from the pile and told me she had been wearing it when she lost her younger brother.

“The siren was wailing, and the air raid started. We all hurried to the bomb shelter our neighbors had dug. I stayed at the entrance of the hole to wait for my brother. He was coming home from work. When I finally saw him running to us, he got hit by the bomb and killed. He was young.

Too young to die, too young to be working even. Anyway, take these kimonos. Maybe you can make a blanket for your husband, yes?”

This was the only time I heard Grandma mention the war.

I later learned that the city of Hamamatsu was air raided 27 times by America in 1944 alone, burning the city to the ground and reducing its population from 190,000 to 80,000 in one year.

I loved my grandma’s tiny courtyard.

The swing set my grandpa made hangs from the beams of the roof. On a sunny afternoon, shiny blue roof tiles made the roof look like the sea.

I would sit on the engawa with my grandma, my little legs dangling, and eat the kumquats she grew in her manicured garden. The fragrant yellow fruits grew on the miniature tree among glossy emerald leaves. “Eat only the skin,” she would say every time. “Just the skin, Akichan. The rest is sour and bitter. We don’t need that.”

My grandma developed dementia when I was in my late 20s, and eventually passed in an assisted living home.

I never went back to Japan after I left.

I don’t know how she changed over time as her dementia progressed.

What left her, and what stayed with her during that time, I have no idea.

Umi No Uta (Song of the Sea)

Sea is wide and big Moon rises from it and sun sets over it I want to float my ship on it someday and visit foreign places on the other side of it How so very far away I have come, and how weathered I look in the mirror these days. Am I still the same person that lived in the busy, neon-bright city on an explosive volcanic island? Now I live in this sleepy city on flat land, thousands of kilometers away from the sea.

My husband’s mother

My husband’s family adored me. More than 40 of them lived 30 minutes away from each other. “We like to take care of each other,” my husband answered when I asked him why they didn’t move away from their parents and try to make it in new places.

His family did take good care of me.

My mother-in-law must have been in her 70s, but was very active and social. She drove me around, took me to the lakes, bought me jeans at Kohl’s, and showed me all the things American.

“Have you seen pancakes before?”

“Here, it’s a recipe for soba noodles. I cut it out from the Star Tribune for you.”

Whenever we had a family potluck, she was fascinated by what I brought. “Here’s Akiko’s Japanese Caesar salad!” “Try Akiko’s Japanese lasagna!”

She would announce things to the family like that, no matter how authentically I made the dish.

As curious and fascinated as she was, she was invested in me. I was her new project. Just like her window treatments and perennial garden in her backyard, there was always something to be improved, and she worked tirelessly.

When I was pregnant with my daughter, she called me and told me our girl’s name should be Kim, because, “All the Asian women I know are named Kim.”

My first five years of life in America was a cocktail of amusement and

resentment. I was thrown from one end of the pendulum to the other. I could never land in the center. I forgot how to just be.

She started showing the signs of dementia after her husband passed.

My husband started to visit her every week, then every other day. When our neighbor moved, he bought their house and moved her in.

By then she was frantic. She knew her memory was leaving her. “I’m slipping,” she’d say. The calendar in her kitchen was black with all the

markings she made—circles that held nothing for her and arrows that led her nowhere. She was desperate to catch what was running away from her, the essence, the anchor of who she was.

Once she moved three houses down from us, I walked to her house every day with coffee cakes and cookies. Sitting in her new kitchen with her, I would explain what would happen that day to ease her anxiety.

“Today, Wendy will visit you.”

“Okay, Wendy will come here?”

“Yes.”

“Why is she coming? What do I do?”

“She is just visiting. She said she wanted to say hi. Maybe you guys can have coffee on the deck?”

“Who am I having coffee on the deck with?”

“Wendy. Wendy will come visit you this afternoon.”

“For what?”

I would repeat myself and mark the calendar with her for hours until I had to go get the kids from the bus stop. When I left, I almost had to peel her off of me and run. One of those afternoons, as I was running out of her house, she chased me, barefoot, in her bathrobe. The wind blew her silver hair madly around her face, and her bathrobe fluttered around her like a sail. As if from a sinking ship in a storm she screamed,

“What do I do now?!”

The next time I saw her, she was no longer living in a panic. She complained about everything in the luxury memory care center she now lived in. The roast beef sandwich and citrus sorbet we had for lunch at their dining room was heavenly, to be honest, but when she asked what I thought about the food I told her the meat was so dry and the sorbet looked like baby food and watched her giggle in satisfaction. We repeated the whole dialogue again and again until I had to leave.

Where do we go, when we go?

Do we leave who we are as we swim forward?

The beach

Once we went to the beach together.

It was one late summer, years ago.

My husband and I visited his parents and we decided to have an impromptu picnic at the lake. My father-in-law was still alive. He was just starting to use a cane, and my mother-in-law was by his side assisting.

We parked our car in the parking lot and walked to the sandy beach. Our two-year-old son was zigzagging and loopy-looping, picking up every rock and stick he saw. Laughing at my husband chasing after him, I slowly waddled in my summer dress, holding my eight-month pregnant belly.

We sat down under the blue- and white-striped parasol and had a late lunch.

Two young boys were playing in the lake, splashing and screaming. A group of teenagers were playing beach volleyball. Leggy girls in bikinis crossed their arms in front of their bodies and whispered to each other. A mother with a stroller watched her toddler making a sand castle.

After my husband took our son to the water, I realized I had left my sunglasses in the car. I tried to find my husband and son, but the surface of the lake looked like a crinkled sheet of gold leaf. Defeated by the sunshine, I closed my eyes and leaned my sleep-deprived, watery body back on the deck chair.

Orange dots bounced around in my eyelids, and my body was sinking fast. Sleep was golden honey.

In my dream-like state we were all there together like pages of a notebook. We are a baby in a stroller, toddler with a sand castle, invincible teenager and exhausted young mother. They never left. Soon I will be passing this moment, But who I am today will always stay with me. Because we are the kaleidoscope of our moments. And passing time is not a loss.

The end