Strange Intimate Archive

A personal archive of this strange land, Minneapolis: on queer dreams, the ghosts of shame, what to keep close and what to set free

1.

Xiaolu, I was a stranger in a strange land and this strangeness has never left me ever since. It’s what Minneapolis did to me, to you, and everyone else. To uncover a personal archive of this strange land would mean to confront the fleeting oddness in us. This archive is not a wooden box, or a steel building or a dark room. It exists in the liminal space where our past keeps speaking to the present, and the present continues to rewrite the past. We were both lovers, liars, strangers, con artists trying new accents, adapting new body language, learning new hand gestures, and abandoning old loves. Our identities and bodies became more and more strange until we mutated into something else on the strange land.

There were days when our joy took us to places we had never been and then snowstorms would come diminish it all. There were kisses outside of trailer homes, again in the snow—only to make it memorable—your first Minneapolis queer lover whispers to you. There were nights when our intimacies became opaque and lingering desire increasingly softened the hard line drawn between friends. For a while, we couldn’t tell who were our friends and who were our lovers. Just like how we tried so hard to sound American while our native tongue stepped back to be a mediator—mediating our insecurities and strangers in us, in this simultaneously new-old and old-new land.

Arriving through your belly That never ceases to dissolve you Once meant the world to me To arrive a new land from the old Shielded within your womb abyss Used to give me vastness Now the shell is slit open Cut through and into our skin Shouting at us Not to arrive New land will not settle you The old land will follow you Until it expels into pieces Pieces that finally calms your pulse

But isn’t it strange to talk about belonging sometimes? Aren’t we all outsiders trying to settle in a land that never belongs to us? When I first moved to America, all I wanted was to be an American. I had internalized the speech-acts of someone who had made their American dream; I had reconfigured my identity so that I’d present myself to be less “Chinese;” I had re-rendered my queer dreams again and again so I could look just a little more similar to the characters from Queer As Folk; I had acted out the stereotypes and reinforced my own interpretations of those stereotypes—parody is the word for it. But America was so much bigger and smaller than everything I could imagine. I remember sipping these words out of my mouth on a drive to a small town in Wisconsin, where I spent Christmas at a friend’s house one year. My friend’s brother had just come back from Australia, and one day he asked me what is like to live in Minneapolis. We came to the conclusion that weirdness does not fully describe the experience of living in the middle part of America.

Eventually, I moved away, so I could reconfigure my relationship with America. Perhaps, this is what it feels like to live somewhere you don’t belong and you will never belong. No one really does besides the ones who were here from the very, very beginning. It took me a while to rewire my brain and when it finally clicked in me, it felt shameful and shameless, liberating and confined, all at once.

2.

Throughout my twenties, I archived all of my thoughts and feelings into one zone, where I’d convolute both and lock them up for as long as I could remember. The high-stress environment of architecture, which I used to be part of, helped facilitate my out-of-touch mental and physical states. I was no longer capable of separating emotions and feelings, thoughts and behaviors, traumas and anxieties. Until one night: I woke up with a pounding heart and I was convinced that I was about to die. I was told repeatedly by doctors that my health was fine and my heart functions were perfectly normal; instead I should seek help elsewhere.

Anxiety made me escape architecture, but when that moment finally came, my anxiety got worse.

In psychiatry, the anxiety caused by the fear of one’s own death is called thanatophobia. I was in disbelief when I heard this term. Sure, I had worries about my health whenever stress arose, but I always managed to repress those racing thoughts; sure, I felt occasional pain or chills in my body, but I never linked them to my emotions. I never knew it was my body trying to process and archive my anxiety—until, all of a sudden, it malfunctioned in the attempt to do so. Psychotherapists believe that the fear of death is a disguise for a deeper concern—if that’s the case, what would mine be?

For years, I had kept my shame or shamelessness from my mother. It was strange—in a way, it was the most public part of me, both in person and on social media; and in front of my mother, I would archive my queerness to the point where my performativity became naturalized. There were times I brought back female friends and pretended they were lovers; there was the fake masculinity; there was even a period where I told her stories of me dating an imaginary Swedish girl—from meeting to intimacy to the final breakup. For mother, my imaginary identity replaced the real one, and eventually became irreplaceable in mother’s psyche.

My father was absent during all of this. Or maybe, I had somehow erased him from all of this. There was a period of time I went to great lengths and wrote about him, but it was uncomfortable. I had to hold my breath every time I dug out pieces of memories and words. Xiaolu, did I ever tell you that the first time I watched Happy Together was with my father? It was a mundane spring afternoon, and my father had borrowed the DVD of the film from his architect best friend. I was doing homework in my room and I heard the quarreling between two men in Cantonese. In our old, small apartment, I peeked from my door gap into the living room, and saw two men lying naked in bed, and my father had his hand down his trunks.

Sprawling down a nameless tower Mother and I are sprawling down The endless steps Caught in between a time and a space Where ghosts flourish Father does not open his mouth for three months For three entire months He was on his way to kill You and your imaginary friend build up train tracks and fake oasis While father endures another summer of silence Home comes and goes in a flash Workers attach and then detach themselves from home Workers tell their father and mother that they will return with new winter jackets While they tell themselves that winter is endless As a child you comfort yourself to sleep You’d dreamed of queer love in order to tuck yourself back to sleep Comes and goes and eventually you Make peace with you came to be Father’s silence is the ghost And mother no longer haunts you

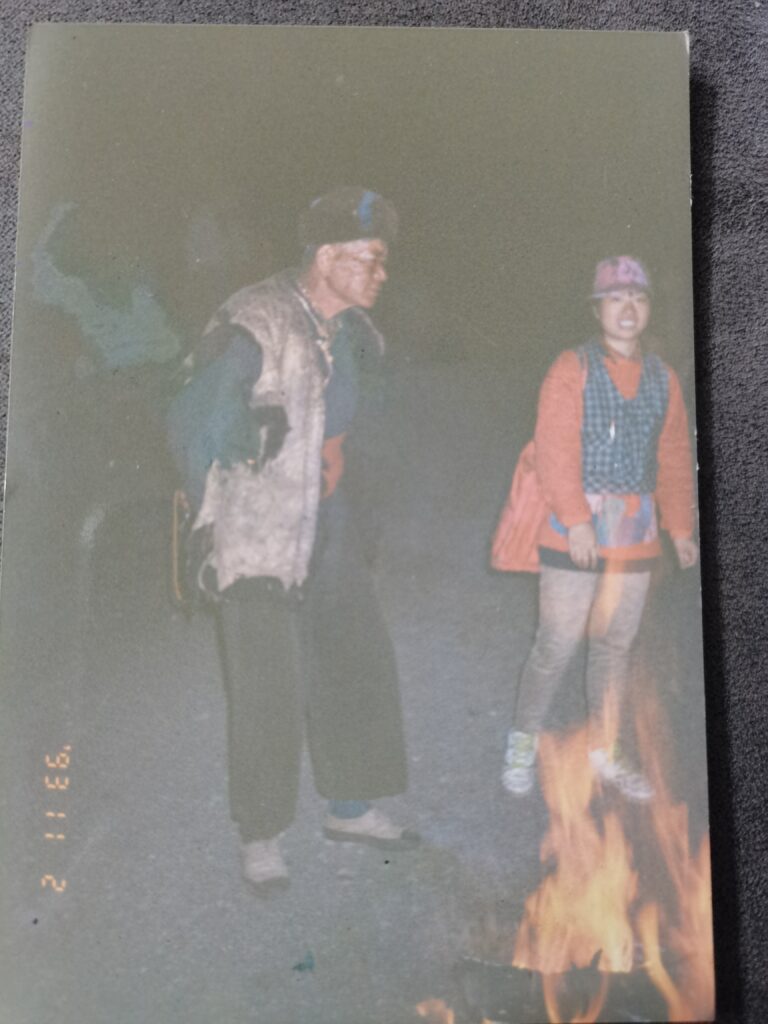

This time last year, when my mother and I stopped speaking completely, I started to trace my mother’s pilgrimage back to Lugu Lake, where the only surviving matriarchal Mosuo tribe currently resides. It felt as if it was something equally caught between memory and reality. Being the only female painter in her immediate circle, she constantly reconstructed her identity in order to fit in. She’d smoke cigarettes in a room full of male painters cursing in local dialect; she’d wear baggy trousers and drink beers in the alleyway by the night market; she’d tell me to stop dancing and dressing up in her night gowns and start acting like a man.

I often wonder, over time, what has she archived and what has she set free? Did she deal with shame the same way I dealt with anxiety, hiding it behind racing, numbing thoughts? When the moment her performative identity became real, was she finally in touch with herself again? Or is it simply too presumptuous for me to speculate at all? Tracing her Lugu Lake trip brought back less peace but more anxiety. The closer I get to the truth of this remote place, the further away I become from my mother. She was also a stranger in a strange land, where her projection might have overpowered the physical place. But aren’t I also making the same mistake? Hasn’t the whole country been making the same mistake for centuries? If intimacy is different from affection, collective intimacy sometimes inevitably extends the opposite of affection to the Other—and instead, pain. The anxiety over depicting, rendering the Other led both my mother and I to abstraction—to blur, to make things intentionally ambivalent, and to reframe the dominant gaze. And perhaps, to perform is sometimes the best way to complicate that gaze.

3.

Xiaolu, the last time we spoke, we talked about being broken and how to avoid fixing that sense of brokenness. It was the first time I’d look at pain differently. In architecture, trauma and space are inextricably linked—our daily affections, horrors and longings belong to certain spaces. As long as you lock the door to trap the ghosts, you will be fine. But what happens when you leave that door open and you can peek into your illicit past? Ghosts flourish and maybe one day we will get used to coexisting with the broken ghosts.

Do you remember that concrete tower where I used to stay? People call it the Chateau. It’s this brutalist structure that stands in midst of nothingness, marking its weird but visible presence. Each wave of newcomers changes the way it smells, sounds, and feels. A friend first took me in and we stayed in the same room for months. Then he moved away and I took another boy in and we stayed together for one night. Then he came to visit me from upstate New York. He slept on the floor for three nights and we stopped talking after that. These days, those nights in the tower often came back to me, reminding me of the cruelty and the tenderness a place can enable, or withhold.

You said to me, to be broken and to fall is as beautiful as healing and flying. These days, I hold your words as tight as possible, our memories as fleeting as possible.

I was born in this place where A stranger’s passing used to mean nothing Towers after towers, cities after cities A stranger became estranged in a strange land Days when the stranger looks through The tower’s dirty pane glasses The city shrinks It keeps shrinking until land can be seen again But land is no longer land Lights are flashing in the forest Lights fade away when you try to catch Land is caught between darkness and light The ship is never gone After landing, we are told we are free We are told we can speak The ship returns and takes us away The anxieties of the new land The ghosts of the old land Break us into pieces Pieces that no longer need to be healed

Chris Zhongtian Yuan

UK, May 5, 2022