Red Dirt Girls

Visual artist, writer, arts activist, and community organizer Shanai Matteson unearths stories of work and water on Minnesota’s Iron Range, weaving her own and other women’s memories to excavate the consequences of a culture of extraction, and untangle what happens when bodies are mined as resources.

noteThis piece engages experiences with ecological and sexualized violence.

We didn’t know exactly when or how the pits were made, but we were told they were dangerous and forbidden.

There was no map to follow.

*

There was no map, but one of us had vague directions.

She’d heard a story, a memory shared by another girl a few years older. This girl had been there before. She knew all the best ways and places, and which paths to avoid if possible.

Following her words carefully, we drove into the pits.

*

He said to me, ‘If you’re old enough to bleed, you’re old enough to butcher.’

I looked over, and he was holding his penis in his hand.

I said no. ‘No, I won’t!’

But I was in his car.

*

The pits were what remained of open pit mining near our town.

The mines were no longer in operation, and hadn’t been for a while.

What was left was a wound in the landscape deserted by industry, a place that was slowly being reclaimed by water and wildlife.

*

We traveled along a minimum maintenance road that had been created by the mining companies. Eventually, we pulled off onto a pair of tire tracks that led into the brush.

When we couldn’t drive any further, we started hiking up the hill. As the story had promised, we came to a downward slope that brought us to a red dirt beach on the other side.

*

He had driven us all the way out on that gravel road, and I was wearing heels.

How could I walk myself home? It was too far.

*

The first time I saw a mine pit lake, I couldn’t believe my eyes.

Was this really northern Minnesota? Was this just a few miles from town, all along?

It was unlike any of the lakes or rivers I’d known.

The water was a surreal blue-green color, enclosed on all sides by steep slopes and jagged cliffs overgrown with small trees.

We removed our shoes and all of our clothes and immersed our bodies in cold water.

*

I tried to walk home anyway, but he followed me, shouting.

He said if I didn’t get back in the car I was going to regret it.

He would tell everyone I was a swamp stomper, a prick tease, a slut.

*

Mining companies call the red dirt that still distinguishes this place overburden.

To them, overburden is the name for waste rock and any life that must be removed in order to extract minerals of monetary value.

In the case of open pit iron mining, earth has to be removed to access the higher-grade ore below. To do this, they blast the rock apart with dynamite, heaping the waste into mounds they called tailings piles.

This process of extraction violently destroys ecological connections and reshapes the landscape, and is what formed the small hills and deep quarry lakes that we came to know as the pits.

When the mining companies were through, the pits filled with water and became a storied place at the edge of a cluster of small towns where mining no longer supported an economy.

*

‘There are wild animals out here!’ he yelled, following me.

‘Girls get attacked all the time by animals, and sometimes they never find their bodies.’

I knew that wasn’t true, at least not the part about animals.

I knew what he was really saying.

*

We’d heard about tragedies that had happened in the pits.

In the 1920s, a mine collapse released a torrent of water, drowning 41 men.

Since then, kids had also gone missing in the water. People who were high could be seen wandering around the edges the pits, seemingly out of their minds.

Still, year after year, young people from surrounding towns would go to the pits to swim in the water, to drink alcohol, to sit around bonfires, or to do whatever required the cover that a used and discarded place like that can provide.

*

He drove us to a place that his family had bought so they could cut and sell the lumber.

There was still an old camper there that his uncle had stayed in when they were cutting it all back.

I think he figured that was where he was going to do it.

*

Rich in iron, the red dirt that distinguishes this place stains everything it touches.

In some cases, the stains resemble dried blood on cloth.

Hematite, or bloodstone, is a high-grade ore. When intact, it looks almost purple. When crushed, it makes a natural dye that turns fabrics dusty pink, red-brown, or bright orange, depending on the acidity of the water and the fiber from which the fabric is woven.

*

I didn’t know the way back except along that gravel road.

I’d have to make a path through the brush and hope I came out safe on the other side, but I worried about how I would cross the river.

All of this went through my mind in an instant.

*

I’ve been gathering earth from mining sites across northern Minnesota’s Iron Range, including the ones I knew as a teenager.

I’ve been using that earth to dye fabrics and textiles that I’ve also gathered from nearby communities, everything from old bed sheets to precise needlework crafted by women over generations.

In the process, I’m also listening to the stories that are woven with those fabrics.

What can they tell me about this place? About my own place within it?

*

A year later, I was at a dance.

I’d just gotten engaged.

I felt warm breath on my neck, turned around, and he was standing there.

I hadn’t seen him since that night.

He grabbed me by my waist, leaned in, and whispered into my ear.

*

Specifically, I’m asking women to tell me about their relationships with land and water, and with the labor that’s part of making a life in an extractive economy.

I ask them about the labor associated with mining, but also about their experiences working in the margins, at other jobs, supporting the needs of their communities, or in their homes raising children and caring for other family.

What did they do or create amid the booms and busts?

How were they shaped by the same processes of extraction and exploitation that shape the landscape?

*

He said, ‘Tonight, you’re mine.’

A chill ran up my spine.

I felt I’d been plunged into ice cold water.

‘You’re mine.’

I told him I was engaged.

I belonged to someone else.

*

These conversations inevitably turn toward violence, even if the women I speak with do not use that word to describe their experience.

Even when they convey a nostalgia for the certainties of the past, it’s not without acknowledgement of related suffering, and a desire for something else.

Some kind of escape.

*

They called it The Deeps.

It was the part of the pit where we understood there was a mine shaft that went down and across. It was impossible to see it from the surface, but if we weren’t careful, we could get caught inside.

*

There was always the possibility of drowning.

Clear water draws us closer, is a mirror.

In the pits I saw myself as a young woman who did not want to live forever in that place. A girl who could not imagine settling down amid so much pressure to perform her given role.

Water was a momentary escape from life above the surface. It flooded me with the feeling that I was always in danger, but also closer to freedom.

I could submerge and climb out, again and again.

I could imagine that the water was magic, that it held memories of other forms it had taken, and that it had the power to transform all it touched.

*

In the course of my work on the Iron Range, women have shared with me their memories of work, and also of water.

Memories of washing and cooking and the way that the iron in well water stains the edge of a basin.

They’ve shared memories of fishing, and the seasons when fish disappeared because water from a tailings pond flowed into surrounding streams, poisoning what lived there.

Smoothing tensions with men who’d had too much to drink, mending what had been broken with their own hands or words.

Crafting careful quilts and crocheting keepsakes while minds wandered inward. Waiting for rain.

*

Women also talked with me about how they were taught what it meant to be good girls, and bad. How to intuit what men wanted them to do—when to do it, and when to fight or protect the safety of their bodies and others.

For the most part, these stories of women and their caregiving labor have been erased from the story of what makes that place, along with all of the small ways they’ve resisted, reimagined, or healed.

*

After we came out of the water, the red dirt stained the bottoms of our feet.

It stained the tires of our cars too, so that afterward, we had to be careful to wash away the evidence of what we’d seen and done.

*

As much as I remember the water in the pits, I also remember how it felt seeing other naked female bodies, all of us trespassing on what was still company land.

I remember how it felt to reveal my flesh to others and to the elements, and not being judged or coerced, but encouraged to dive deeper.

The feeling of cool water against my skin.

*

I remember sitting in my bathtub later, closing my eyes and dreaming about the blue-green water of the pit lake and the wide sky above.

As a friend said to me recently, sharing her own water story about a swim to the middle of a lake, and the fleeting peace she found while lying on her back in the water:

‘This view of the horizon, as a circle with my body buoyant at the center, is as real as any other.’

*

For all the violence that created the pits, they still offered a moment of liberation.

I could be naked and surrounded on all sides by steep slopes that had been carved in explosions, and still experience a sense of calm.

I didn’t yet understand these contradictions.

It would take me decades to learn how my body, and my sense of who I am, has always been shaped by the violence of extraction, as well as by the life-giving and healing power of water and women’s care.

*

Our family was big, and we were poor.

We didn’t have a shower in our home.

I often felt confined in our tiny house, so I’d take long baths. It was the only time and space I had to myself.

After trips to the pits, I would scrub hard to remove the red stains from the bottoms of my feet.

I couldn’t tell my mom where I’d been, or that I’d tasted that kind of freedom.

She’d grown up in the shadow of a man who worked in those same pits, and whose wife—my grandmother—had violent stories of her own.

*

I don’t remember wondering at that time about how or why people would allow such devastation in the place they live, or how they could continue to work in such conditions.

I knew about mining, but I always assumed that the worst exploitation of land or workers’ lives was soemthing that happened in the distant past, before people knew better.

I couldn’t see how the story of extraction as our way of life had become so ingrained into that landscape and culture that it was still shaping our lives and relationships.

The everyday violence we experienced as young women growing up in the 1990s was not entirely different from what our grandmothers had experienced two generations before, and it all made that economy seem inevitable to us.

The violence families like mine had perpetuated and experienced was not entirely different from the violence that had brought us there in the first place, settlers on stolen Anishinaabe land. Land that was stolen so that resources could be extracted from it by people like us.

Our labor, both in and outside the mines and other extractive industries, was instrumental in a larger story of extraction and wealth accumulation that is ongoing to this day. And that story, that process, would not be possible without subjugating women, devaluing our caregiving and reproductive labor, and using sexualized violence to maintain a hierarchy of power.

Our sexuality—and the assumption that in addition to caregiving labor and reproduction, we would also provide our bodies as objects of pleasure, or something for men to have power over—is another violence we learned to incorporate into our identities.

It always defined our experience, and who we imagined we were and would become.

*

When I travel north now to collect material and engage with communities, it’s a kind of homecoming, though I carry with me all the problems of home that I’ve come to realize only after leaving.

Once you see the ways that violence permeates a landscape and a culture, your own culture, it becomes impossible to live without seeing it in nearly every interaction.

It becomes a choice whether or not to continue accepting it. Can you live with it, both outside your body, and within?

I cannot accept it, and can’t live with it, so I continue to look for ways that I can make the injustice clear.

And once it is clear, how do I begin to heal?

*

My grandmother taught me how to sew when I was a child.

Her style of sewing isn’t precise. I don’t even think she owns a measuring tape.

What my grandmother does is she scraps things together, using her body to measure.

She does the planning and design in her head.

*

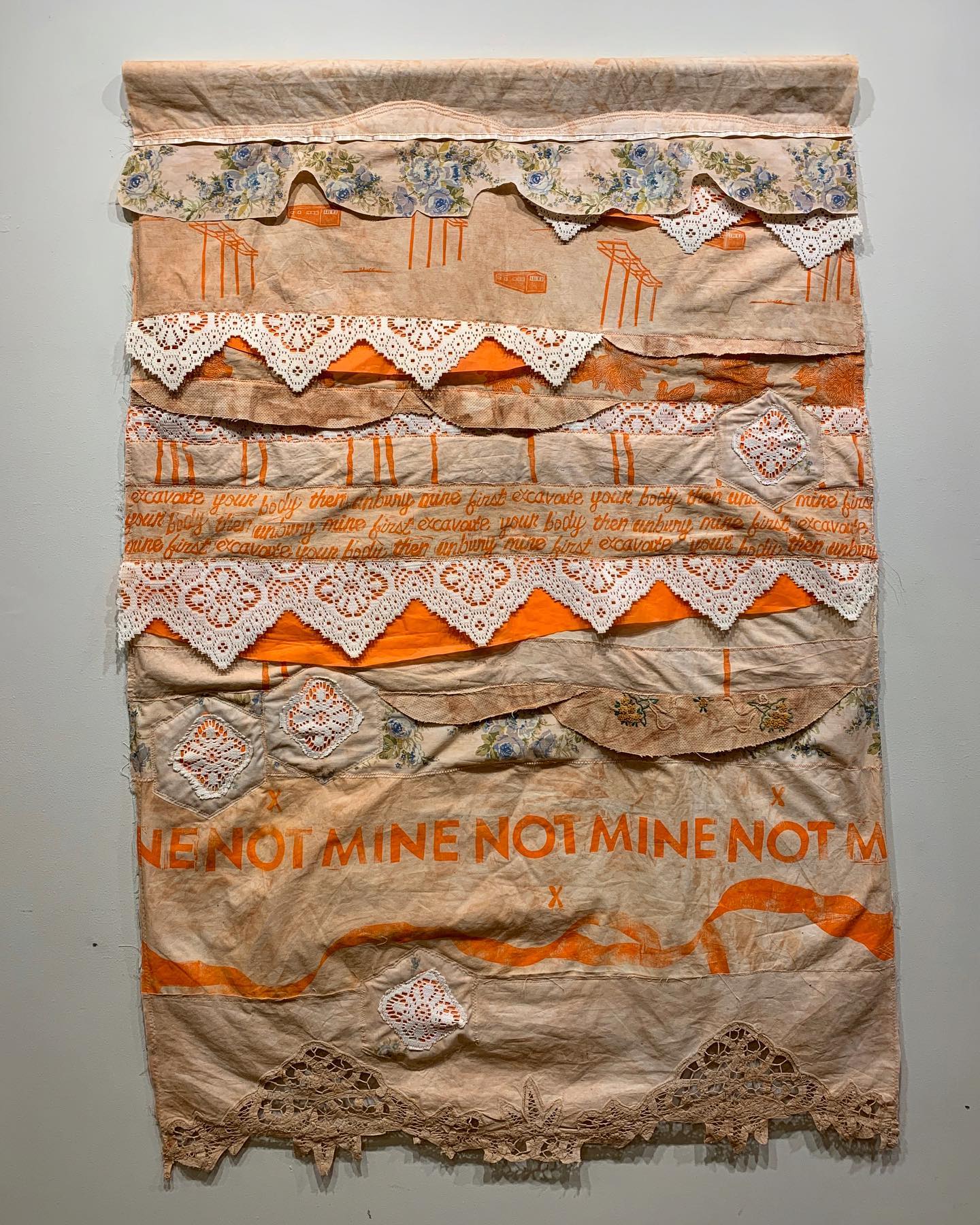

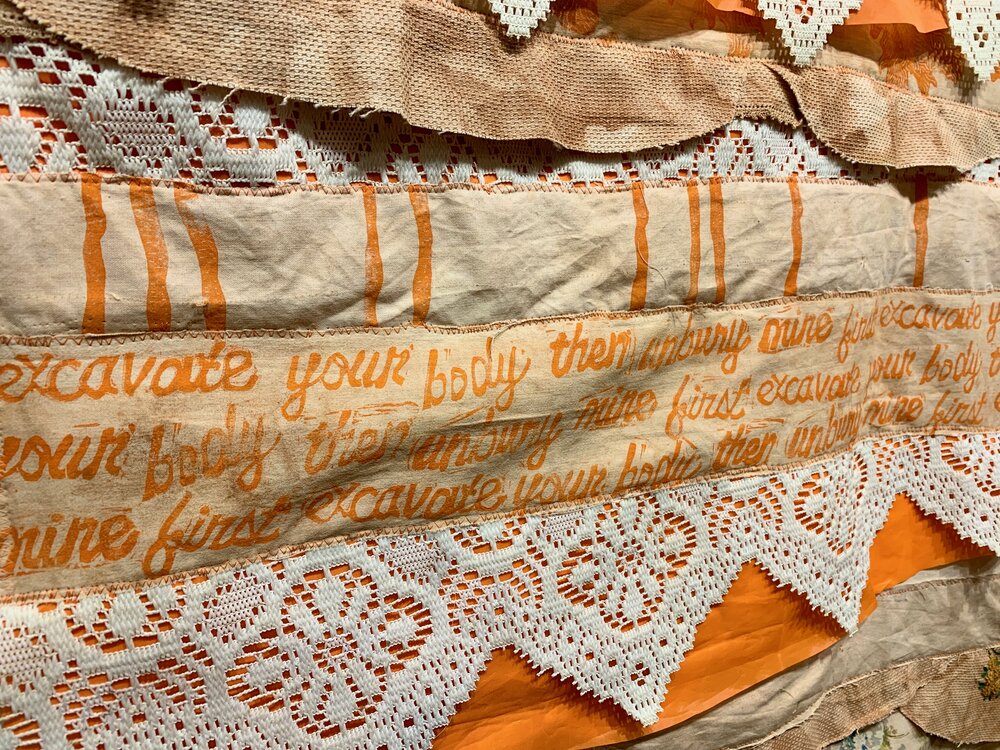

I’ve been using fabric and fiber that I’ve gathered from her and other women to create relief prints, which I also stitch together in a process that’s very intuitive.

I stitch these together into story quilts, onto bandanas, or small utility flags.

In different ways, these pieces mark what I’ve come to think of as my work site, in and outside of home. They carry phrases and symbols that are layered with meaning and relationship, as well as mineral pigment I’ve made from earth gathered at sites of violent opening and shaping.

Rather than creating objects for others to view at a distance, I’m focused on the tactile process of dyeing, sewing, or weaving with this material.

As I do this work with my hands, they become red, and I remember my own stories.

I invite others to join me.

*

I invite them to feel the tiny pieces of grit and water as they roll a felted wool pellet or press a block to make a print.

While we do this work together, we unearth.

We’re practicing what it means to transform material that’s been imagined as an extractible resource in one story, into something that can help us honor others and transform ourselves, a new kind of ritual.

I call the public workshop space that I make for and with other women Felt Here.

Felt Here is a creative work space, but it’s also a space to ask how we might begin to heal our relationships, by weaving back together our once-buried stories.

*

How can we recognize the violence that reverberates inside us?

Violence we were raised to believe was inevitable, a part of who we are, a pathway to our future, or a boundary we must observe?

How do we remember that all along, there was a river under that river, a thread that women have always been weaving between us? How do we remember the maps not written down, directions conveyed in stories or through looks weighted with meaning?

*

Recently, my grandmother began telling me her stories, the ones that she couldn’t tell while my grandpa was still alive.

He had worked in the mines, and his family had just come to this country when she met him.

Before she met him, she’d lived another life.

That life included a violent education in what it meant to be female and poor in a place and culture organized to extract.

In many ways, this education prepared her for life as the wife of an immigrant miner.

*

When they would blast, if the wind was just right, a cloud of red dust would blow through our trailer house—the house we lived in—in the company town.

It left a fine grit on everything… Our dishes, the glass in our picture frames, on our teeth.

None of us liked living there, but it was closer to the work.

The work was dangerous, but what choice did we have?

*

I made this piece to honor my grandmother, her told and untold stories, and others I’ve heard echoing around those pits, and inside myself.

I recognize that violence is a relationship.

Ownership and taking from, these are relationships too.

But at the edges, in the margins and the middles and the in-betweens, there is still the possibility of something else.

Repair and healing are possible, even amid destruction.

*

After your grandfather died, I looked him up.

I called his family, and I told them that I wanted to see him.

His daughter brought him to me.

We sat down at this table.

*

I remember seeing myself in the water of that bathtub too, murky from the red earth I’d washed from my feet.

*

I told him like I’m telling you.

What he’d done all those years ago did not define me, but it did cause me immeasurable heartache.

*

If water can remember and transform, so can we.

All images courtesy of the author.

This article is part of the series by guest editor Christina Schmid