The Railway Bolt Pulling Itself Off the Rail, Turning Into a Cloud 一 枚铆钉从铁轨上挣脱变成了一朵云

A meeting of friends, from Minneapolis to 苍山 Cang Mountain: on workplace cultures of exhaustion, the legacy of Chinese laborers in the United States, and intimate relationships with objects

The last time I went back to China, I had only just met Peng. That was 2019. He was working on a project about sleep, or rather, as a result of his sleeplessness. I had completed my first short film and started to call myself a filmmaker.

We have been orbiting around each other, for 10-ish years, in the same city where we ended up because of our education—in a micro-scale. Peng relocated to Minnesota for grad school in 2011, and I started college in the fall of 2010. In a larger sense, it was probably the destiny of being brought here, getting trained as an exhausted alien worker serving the system of colonialism—the destiny that is powered by looted resources on stolen lands.

During the years before our destined meeting, our lives seemed parallel with vague traces of intersection. We tried to assimilate with whiteness, to be critical of our Chineseness, to understand what is in between the cracks, to get validation from groups with power and resources, to make sense of identities that are mostly limiting labels, to believe in a self that doesn’t exist. But there’s a voice somewhere inside both of us, longing for a deeper connection with ancestral knowledge and history. We both realized much later on that that knowledge and history is, by design, kept away from us. It has been such a detour—requiring patience and seemingly wasted time—to unlearn what our education deemed important to highlight, to let the hidden knowledge reveal itself.

I had a three-hour conversation with Peng to compare notes on our journey of unlearning and to prepare for this piece. On a whim, we went up to 苍山 Cang Mountain, which is always covered by ever-changing clouds at Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture. We went up the mountain by cable car. The air was wet and refreshing. The thin line of the cable car extended into the mist and disappeared in front of us. We found ourselves amidst the clouds. We became a part of the clouds.

About 150 years ago, migration was also cloud-like. The clouds: drifting, shifting, floating across the borders. Guaranteed by the treaty between the two counties, no passport and no visa was required at the border. No interrogation, humiliation, and violence in detention centers. Under one small umbrella, we walked in rain clouds. Peng started to share how he ran into the mysterious railway bolt on a walk during his lunch break. Much later on, the bolt, like a key, opened the door of the marginalized history of his ancestors.

Eating lunch at his corporate job was an awkward time. Among mostly white colleagues, there were two Chinese workers who always sat together quietly at one table by themselves. The white colleagues sat together by combining more tables into a large table. The lunchroom was filled with their voices and occasional laughter. Peng carefully observed, tried various sitting scenarios: with the Chinese, with the bigger group, and alone. Soon he ended up going out for lunch every day, either to the Super Taco or the Vietnamese noodle deli. Peng couldn’t get used to the short lunch break allowed in American corporate culture. In China, the culture of taking noon naps is allowed even in the most intense workplaces. So Peng always walked to a nearby park and took a short nap on the park bench. Laying on the bench staring at the tree crowns and clouds brought some rest to the exhaustion of being a cultural misfit. One day during his break, he took a new route to the nearby train tracks.

He walked along the rails until a railway bolt spoke to him. The bolt seemed to decide not to fit into the rail and lay on the gravel by the wood rail sleepers. The heaviness and rustiness of the big bolt was unusual; time was its secret. Peng carried it in his pocket and brought it home. Like countless childhood memories, he’d collect objects found on the road and play with them as toys. The mysterious bolt sat at a corner in the basement for a long time, accompanying Peng’s sleepless nights when he had been moonlighting for his art projects. After years of moonlighting, he managed to switch his visa to a different type that allowed him to focus on art making. The long story of navigating through different visa types can be found in his own writing. Following the thread of collecting the immigrant stories of Minnesota for the art project CarryOn Homes, Peng encountered stories of building the first U.S. transcontinental railroad, for which the earliest large group of Chinese laborers were brought to America. The dark history was unveiled only recently in 2020 by Gordon Chang1, a historian at Stanford University, 150 years after the completion of the railroad. The bolt emerged again. Years have passed since the bolt found Peng. He described the spiritual moment of realization: it’s like the ghost of our ancestors had spoken to us, but only when we are ready to listen we understand. And only when others in our own community devoted their lives to listen.

Through our conversation I learned that our ancestors were lured to California for the gold mountain initially, and found that these mines had been taken over by the whites. Later, many more Chinese laborers were brought to California by the Central Pacific Railroad company directly from south China, Guangdong province. They arrived as coolies or indentured laborers, which meant they would have to work years to pay off the cost of living and overseas ship ticket. The north had won the Civil War and abolished slavery. The Chinese coolie became the substitute desperately needed. During the construction of the west line of railroad operated by the Central Pacific Railroad, more than 12,000 Chinese workers were hired: “at that time the largest industrial workforce in American history, made up 90 percent of the Central Pacific’s total labor force.”2 During the six years of construction, more than 1000 workers died from explosion accidents, being buried under snow, plague, poor living conditions, and exhaustion from overwork—about a 10 percent death rate. However, in the photo of the celebration of the railroad completion, where more than 100 white railroad workers climbed onto the locomotives shaking hands, we could barely find one Chinese person. Othered and dehumanized, Chinese coolies were deemed obviously not appropriate to be invited to this important historical moment. The white supremacy and othering of alien labor is perpetuated in the work space today. Peng shares this story:

“When I worked for a corporation here as a graphic designer, I worked 60 hours a week for weeks to meet the deadline of a trade show project in Las Vegas. After the trade show, everyone got drunk in Las Vegas as a routine team bonding activity, which I always found awkward but was obligated to attend. Afterwards, I walked with a British colleague to the boarding gate in the airport. Out of nowhere, the colleague asked me: ‘Are you a Chinese traitor?’ I thought I must have heard it wrong, so I asked: ‘What?’ My colleague repeated the same question. Now as I try to recall the moment, it felt like I heard a voice coming from far away and centuries ago. Feeling shocked and shamed, I remained silent and walked faster toward the boarding gate, leaving my colleague behind, as if the business trip would end sooner if I got in the airplane faster. After I passed the gate, behind me the staff refused to let my colleague enter as he obviously looked very drunk. I still don’t know why—maybe out of the obligation of being a model minority—I walked to the staff and told him: ’It’s okay, I will take care of him.’ Eventually the staff let us pass. I pretended nothing happened afterwards, and so did my colleague. It was a bitter thing to swallow. Everything looked fine in the office but it never felt the same to me. And I kept it to myself until today, as I felt ashamed that I didn’t have the courage to complain in the moment. It took me years to encounter others’ stories like that, which makes me feel okay to share mine. And I feel so fortunate to be an artist who is given space to tell stories like this.”

The completion of the transcontinental railroad enabled the whites to further invade the central area of the continent from the east, where Indigenous tribes retreated to survive. Genocide followed. What came to the Chinese coolies was lynching from the white mob in California, followed by the Chinese Exclusion Act3: the very first U.S. immigration law that forbade one entire race to enter the country. To make the exclusion and lynching legal, the treaty mentioned above had to be removed.

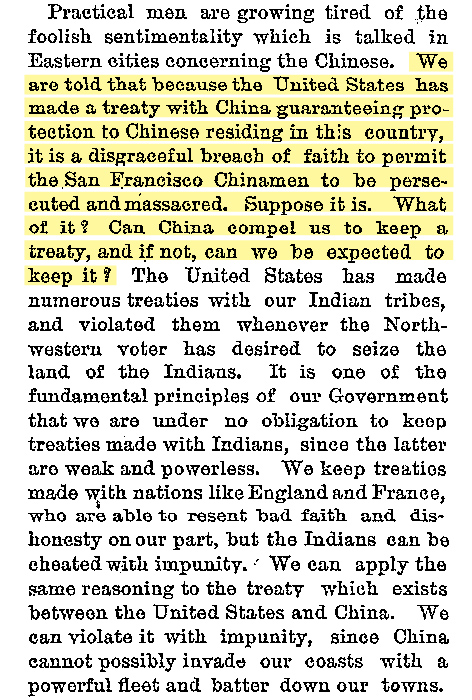

“We are told that because the United States has made a treaty with China guaranteeing protection to Chinese residing in this country, it is a disgraceful breach of faith to permit the San Francisco Chinamen to be persecuted and massacred. Suppose it is. What of it? Can China compel us to keep a treaty, and if not, can we be expected to keep it?”

“The Chinese Must Go,” New York Times, February 20, 18804

To give context for this bold and shameless article, the treaty mentioned is called the Burlingame Treaty5 of 1868, which allows the citizens of both countries to freely visit or reside in the other country while being protected and treated equally as if they were the citizens of the other country. The violation of the Burlingame treaty eventually led to the Chinese Exclusion Act, which lasted more than 60 years, and was followed by nationality quotas, an immigration system that practically banned Chinese immigrants for another 25 years. Only after 1968, Chinese immigrants—together with Latin American immigrants—started to drastically increase.

The history of building the transcontinental railroad is a showcase of the centuries-long colonial operation: how looted resources financed colonialism in the name of civilization and development, which nevertheless resulted in genocide of Indigenous peoples and the displacement of alien laborers. Though not commensurate with the Afro-Atlantic slave trade to the Americas, the history of Asian coolie labor is marked by debt peonage contracts and by horrific conditions of living and working.6

“It brought tremendous clarity to my 12 years of living in the U.S. and beyond. I realized I have been shaped by the expansion of white supremacy, along with West-led globalization, before I ever entered the U.S.” Peng said. He imagined how the railway bolt that found him was made with iron extracted from a mine in China. Then it was forged in a Chinese factory along with millions of others to precisely fit into the rails in the United States. It holds the two rails together that endured the heavy weight of cargo trains. Sun and rain, day and night, year after year. One day it somehow decided to pull itself out. It seems to me quite naturally that Peng started to create plaster molds of the mysterious bolt, as well as ceramic copies of it. One particular copy caught my eye. It is a shining porcelain bolt covered with jade green glaze. It’s softly bent at the upper middle area. It was positioned leaning against a vertical support like it’s sitting on the floor and resting.

Peng shared how the piece is linked to a journalist’s story published during the construction of the transcontinental railroad:

“The journalist was sent from the East Coast to report on the progress of the construction, as the funding of the construction is determined by public confidence in the ambitious project. The journalist arranged to ride the train in order to experience the completed section of the railway. Through the train window, he saw from a distance there was someone sitting underneath a tree, leaning against the tree trunk on the other side. When the train approached closer and passed the tree, he was able to see closer and had a better view of the ‘resting man,’ which didn’t look alive. He confirmed with the guide that it was the body of a Chinese railroad worker. Without exception, the Chinese local organizations were responsible for shipping the dead bodies back to China to bury, which is part of the indentured labor contract (and of course it was paid through a portion of their wages.) But for a period of time, there were so many deaths that some bodies had to be left by the rail before they could be collected. Based on the research done by Gordon Chang, Chinese workers went on strike—the largest strike in America’s history to that date—to fight for equal pay and 12 hours as the maximum working length per day. I imagined only death allowed them to have the luxury of having a long rest in peace under a tree. I imagined that my body laying on the bench under a tree overlapped with my ancestors’ bodies. I felt grateful I was breathing and still had the chance of pulling myself off ‘the rail.’”

Peng projected his own fate onto the bolt in order to find his bearings in the history of immigration. That’s how history gives us perspective that goes beyond our own short life span as an individual human. What has happened before to people like us affects how we are seen and treated today. The Page Act of 18757, the first federal immigration law, effectively prohibited the entry of Chinese women, accusing them of engaging in prostitution. Today, Asian females are hypersexualized and subjugated to sexual harassment and hate crimes, like the shooting spree at three Atlanta spas in 2021. Asian male laborers, however, are desexualized, which has to do with not being able to bring their wives and children to live with them. This also became the seed of the laundry business because they had to wash their own clothes without their wives. Peng told me how shocked and ashamed he felt when a schoolmate told him that “Asian boys are a bit pussy.” It would be almost revolutionary if a chapter on “desexualization and hypersexualization of Asians and their origins” were printed on the manual of the Welcome to the United States of America brochure—those handy little navy blue booklets that are distributed for free when an alien resident’s visa is approved at the U.S. embassy.

Peng told me he almost forgot how many white male artists were his inspirations when he dreamed of an artist’s career back in China. He sees his early years repeated every time when he gives studio visits to art students from China. In an almost predictable manner, the Chinese international students would bring up the few “master” artists, who also happen to be white, male, and American. After all, that is what the U.S. art power machine has exported to the rest of the world. Both of us stopped going to museums and art shows willingly a couple of years ago. Maybe the least we could do to unlearn is not paying that much attention to the validation machine, but to reclaim our attention on where our curiosity resonates.

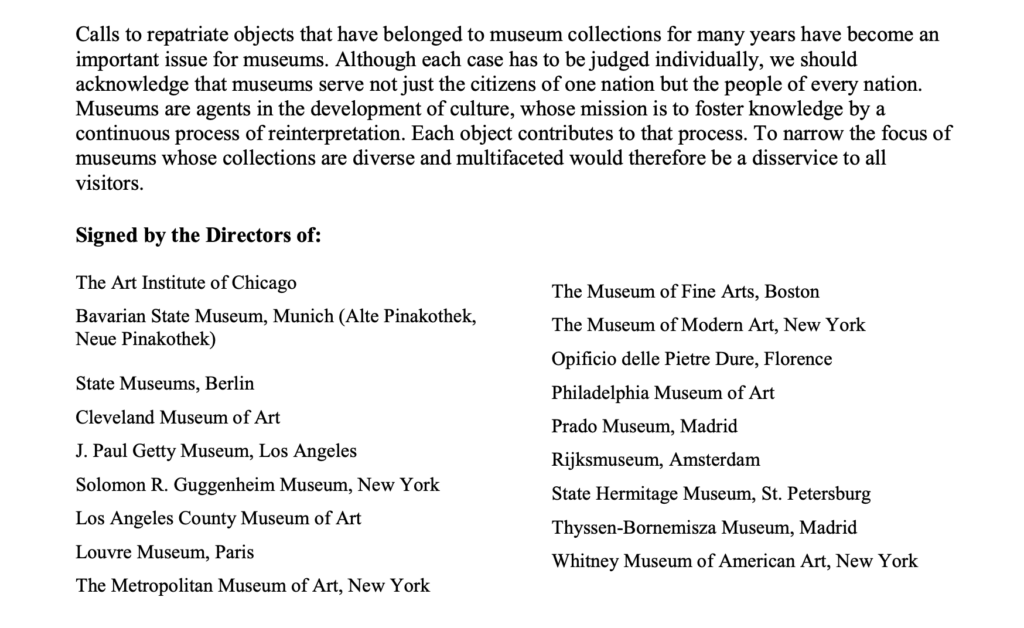

Coincidently, I first met Peng in a museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art—because I noticed his hands at an event. This museum, where I worked as a videographer before declaring myself a filmmaker, also hosts the largest jade carving outside of China, the beloved Jade Mountain. Peng passed this sculpture over the years as an art student, a museum visitor, an artist-researcher, and a professor without knowing how it ended up there. This particular sculpture, along with many objects recently exhibited in China’s Hidden Century 晚清百态 at the British Museum, were looted from the Summer Palace8.

Peng sent me an informational video9 about looted art objects, and I encountered this “declaration on the importance and value of universal museums” signed by major European and American museums who conveniently praise the importance of their work. I find the language of “each case has to be judged individually” a poor but long-sustained excuse for colonial violence. The declaration advocates for museums as universal institutions that hold artifacts in one place on behalf of humanity. But as Fatema Ahmed responded: “I think the claim to universality isn’t the strongest claim that a museum can make because to some extent it retraces some of the language of colonialism—that the colonizer is universal but you are specific.”10 The declaration also talks about “a disservice to all visitors.” It ironically doesn’t consider the global majority, who neither have the privilege to cross borders, nor can afford to travel across continents—particularly people of the culture where these objects were looted from. Not to mention that 90 percent of the collection is not open to anyone most of the time.

A boat-load of coolies can be brought over for indentured labor, their bodies can be discarded, replaced, calculated, and undocumented, but if they ever want to live under the same constitution and dream the same “pursuit of happiness,” they have to be judged individually. The government couldn’t be more eager to x-ray their entire lineage and associations. When an object is desired, there’s plenty of room to host it. But when it is not valued, a magnifying glass is omnipresent to examine the flaws.

Our conversation ended on a lighter note. Peng spends most of his time building a community of belonging as a part of his art practice. I am honored that this community also includes me: I lived with them under one roof for a year, along with two cats, 100 plants, a giant table where clay-making, craftsmanship, conversations, meal-sharing happens, and an entire basement of “junk” toys. Peng and his partner got married officially in Minnesota, and I was a witness at the courthouse. After years of keeping his queer identity a secret to his family, his mother and the partner’s mother met in Yunnan Province 云南 (literally translated as “the south of clouds”) a week before our conversation. Peng felt a sense of relief that both mothers accepted them and the relationship. This was unimaginable at the time that Peng wanted to leave China and felt the pressure to become someone who he is not. But now his marriage is invalid in China, while his Chinese identity is considered something indefinitely foreign in this land of “freedom.”

I remember vividly that one day Peng and I took a walk together. I was suffering about something that I wanted to assert control over. Whether intentionally or not, Peng called my attention to the clouds and the sky. “Do you think the clouds ever feel crowded?” I smiled. Peng’s humor and riddle-like expressions can always pull me out of a funk. It was an insightful moment. Could we learn something from the drifting clouds, perhaps some ease and grace, and maybe more imagination to evolve, shapeshift, and play as we navigate on land across borders?

After our departure, Peng went to an artist residency program at Taoxichuan International Studio in Jingdezhen City: the “Porcelain Capital,” renowned for its ancient porcelain production that stretches back more than 1700 years. During the residency he started to create the Cloud Series. However, they are unlike “fine art” sculptures for pedestals and white walls. These are objects with practical functions: flower vases, bowls, tea cups, table lamps, book stands. They are created not to show off the aesthetic taste and social class, but to tell stories of our ancestral knowledge and marginalized histories. This is much like how ceramic homewares of thousands years ago tell intimate stories of human communities from before the invention of fine art and art institutions. It is the wish of the artist that if an alien finds these porcelains in the future, they can decode their narratives as an act of resistance. We hope intimate relationships with these objects can be developed through wear and tear and repairs. It is a kind of life force speaking, like the stray bolt, only to those who are curious and listening.

Note: Even though the article is written from the point of view of Xiaolu, the writing was a collaborative process. We use “we” and mean it.