Plied in Bed

Considering the bed as a place of exchanges and introducing a series of articles on sleep and its material culture

In a recent online survey designed to learn of people’s strangest behaviors while in self-isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, respondents around the world mentioned sleep. Some acknowledged that the pandemic was helping them compensate for the sleep deficit they had been suffering, often without recognizing it. For others bedtime was an escape plan. One respondent confessed, “I have never slept as much before . . . I felt I needed to sink into this hibernation, and then all of this would end somehow . . . but it just wouldn’t end.”1

Contemporary studies of sleep have shown how within a capitalist ideology of infinite economic growth, the aggressive global inculcation and glorification of sleeplessness as a sign of productivity and prowess have resulted in irreversible damage to the physical and mental health of entire nations.2 Maybe it takes a pandemic to begin to understand and appreciate the indispensable value of a peaceful bedtime. The debasement of rest and the refusal to sleep (to take a break, to reflect, to dream) facilitated the relentless exploitation of natural resources and people: our global nightmares today.

The transfer from biological time linked to the natural cycles of the planet and the human body to industrial time, maintained by mechanical clocks, artificial light, and the principle of division of labor, allowed “all the time in the world” to be split into shifts and breaks, regulated and animated by the ideas of effectivity, diligence, and progress.3 In this way the industrial revolution wreaked havoc on the natural world and on human rest, but, ironically, it provided almost everyone with a sheet to sleep on.

Bed, in its multiple shapes, is the most common ground for sleeping, dreaming, loving, dying, giving birth, lying sick, having insomnia (and thus again, dreaming or reflecting), being with someone, or being alone. Bed is a very intimate place—and also a place of negotiation between public and private.

It is a place of exchanges: internal and external, pleasure and suffering, the mundane and the extraordinary, remembering and forgetting, being tortured by consciousness or anticipation (sleeplessness) or escaping them into the void (almost death) or into the dream. It’s a place to collapse and to regain strength. It is for the body in its entirety: it is felt with the skin; it’s all touch and movement, even if you are simply lying still. It is a place where gravity reigns and is allowed, but then it is also a place of flight—metaphorical, but entirely physiological, as all our mental processes are.

It is a place where boundaries are questioned and reestablished. It is a place to loosen or lose oneself, to relax. Often this haunting desire of relaxation is not granted; then it is suffering, or overexcitement. “I cannot sleep, nanny, I cannot sleep. I wait for a letter,” says the love-stricken Tatyana in Alexander Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. We read in bed, don’t we? Sleepless, restless, or exhausted, falling out of being in control, fading into dream, or hallucination, on the border of consciousness, on the threshold. Bed is a liminal place.

Then there is the deprivation of sleep. There is a bed but you cannot use it, cannot reach it. When your sleep is in the possession of someone else, it becomes torture. Subjected to sleep deprivation, you might tell the truth. What truth? I want to sleep—I’ll tell you anything, anything you’ve ever dreamed of.

We all share the necessity of sleep, but we go about the sleeping place in different ways in different places and times.4 Cultures with nomadic heritage show preference toward sleeping low, close to the ground, on sleeping implements that can be rolled, packed, and easily transported. The nomadic dwelling, the tent, has many purposes and cannot be dedicated solely to sleep; this sleeping place during the night is a place of lively activity during the day.

Carpets and rugs of Middle Eastern cultures are elaborate manifestations of the multifunctional supertextiles, serving as ground, furniture, and walls of the tent. Like the simplest of their countrymen, the Turkish Ottoman rulers slept on the floor on rugs and pads until the nineteenth century, when European habits, including elevated sleep, began to infiltrate upper Ottoman society. In Japan the traditional floor mats (tatami) and the futon floor sleeping set of cotton-filled mattress and heavy coverlet are still present and were internationally adopted during the past 50 years as variations of foldable futon beds. Besides animal hides, the woolen carpet and the plaited plant-based fiber (or plastic) mat are probably the most ancient forms of floor beds still common throughout the world, including the sleeping mats from Borneo and Vietnam and those created by the Native American Ojibwe people, among many others.

Often (yet not always) the more settled a society becomes, the farther it removes itself from the damp and cold ground during sleep, and the bedstead elevates its sleepers more the higher their rank. Even having a bed can be a sign of status, as in the log houses of 18th-century New England settlers, where only the parents slept on a folding bed near the fireplace while the children had to be content with floorboards in the attic.

Since antiquity the bed was often the most lavish and elaborate piece of furniture. It was not only used but also displayed, even outside the house. The basic elements that construct a bed are shared across the globe: platform, legs, posts, canopy. Once such a wonder is in the home it makes sense to use it for more than sleep or sex, so we, like our ancestors, might engage the bed as a dining, working, entertainment, and social life platform. We often disregard the prudish commandments of Protestant ethics condemning laziness: with unwillingness to leave the bed, and refusing to separate the vigor of wakefulness and productive activity from the temptation of stretching bedtime into daydreaming. Yet with the ever-increasing digitization of our private and work lives, and the resulting erasure of boundaries between them, accompanied by fatigue and insomnia—separation between rest and work, motivated by self-care, rather than self-reproach, becomes necessary.

To escape cold drafts but also to display family status and enjoy a degree of privacy, many cultures resorted to bed curtains and canopies, enclosing the bed entirely. A rich conjugal bed in China of the Han dynasty would be enclosed completely in silk bed curtains, creations of weavers who worked on the most elaborate draw looms. In Dutch, Swedish, or Breton cupboard or closet beds, the sides and back of the bed frame grew into a whole wooden enclosure, complete with curtains and footstep, forming a house within a house. Contrarily, cultures thriving in the hot climates of South Asia from India to Afghanistan practice sleeping high, often outside the house during daytime, on charpai or manji, a light, easily ventilated, and movable bed made of ropes or bands stretched and interwoven on wooden or metal frames, with none or minimal bedding.

Contemporary living spaces in the densely populated (and, as a consequence, increasingly costly) cities reveal a peculiar resemblance to the tent. A studio apartment or a single rented room with a folding bed or futon, compact furniture, and built-in facilities are the completely inverted echoes of the multifunctional tents. While the latter were motivated by movement and abundance of physical expanse, the former are circumscribed by an extreme lack of both.

Like the nomadic tent, the traditional peasant house often lacks internal divisions for the specialized spaces we take for granted today, such as the bedroom, kitchen, dining room, and so on. It is a multifunctional open space that sometimes cannot accommodate a dedicated piece of furniture such as a bed. Russian serfs slept on wooden benches that were used for sitting during the day; on top of wooden chests that were used for storage; and on huge stoves that were especially designed so that their surface would be safe to touch, a solution for sleeping in a very cold climate.

When a bed existed in such peasant dwellings, shared sleep was the accepted and frequently the only available practice. Not just the married couple of the family, but grandparents, children, grandchildren, and servants also shared the beds.5 We owe the idea of a bedroom as it is understood in the West today to the 19th-century bourgeois invention of family privacy, based on separation of the living quarters from the working or trade space. The conjugal bedroom was sanctified as the heart of “civilized” domesticity in the emergence of suburbia during the industrial revolution. In the context of such separation and increased scientific concern with hygiene (focused on the quality of indoor air that was ever endangered by the contaminating pollution of human excretions), shared sleep was considered utterly unacceptable, resulting in the concept of twin beds, that is, two separate beds for the married couple.6 The expression “twin bed” today, indicating a bed for one person, is the echo of that fashion. In fact, the practice of shared sleep continued well into the 20th century and is not abandoned today, as many people even in the “developed world” simply cannot afford a separate room or a separate bed. A sumptuous private conjugal bedroom and bedrooms for each of the family’s children, all equipped with welcoming beds, remain important attributes of the dream of upward mobility.

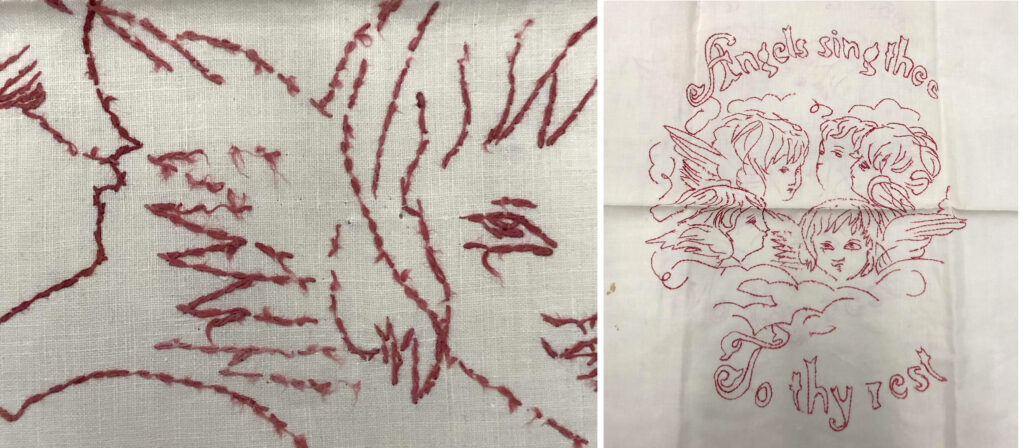

An entire culture of bed-related textiles (mattresses, pillows, blankets, sheets, pillowcases, covers of many kinds) physically furnishes all the in-bed activities. These textiles absorb stains, benefit hygiene, and provide support and comfort. Indirectly, in a mediated way through design and choice, the linens become a material sign of a particular identity—a significant sign, because bed is a significant place.

How we arrange the bed and treat the bed linen are also meaningful: changing, washing, ironing, folding, storing are rituals of order, care, discipline, and desire. Make your bed. A linen closet can reveal something about the person who owns it. Her closet is perfectly ordered. Do you iron sheets? Who are you? In Europe in the Middle Ages, a custom of dowry, a trousseau chest (later known as the armoire), developed; a substantial part of the dowry was bed linen. A culture flourished in various parts of the world that was named “the white linen civilization” by the French historian Michelle Perrot, recognized for her study of the history of private life and of women in the West.7 Amassing, storing, caring, marking, and embellishing the bed linen (along with table linen and lingerie) was both a female domestic craft of daughters and wives and a profession of linen maids. It was also a source of income and profit for textile manufacture in its many iterations and historic appearances, from cottage industry to mass-producing factories to boutique enterprises.

The witness of bed sheets carried a symbolic load closely linked to the everyday functions of this textile and its encounter with the body. White, pure, virgin, innocent, honest, decent: the sheet, just as the (female) body became a subject of anxiety and attention, of keeping and washing, dreading and expecting the unavoidable appearance of stains. Stains, depending on the context, could be “good”, a sign of a consummated marriage, or bad and devastating, shameful traces of an unauthorised liaison, of purity lost and never to be regained. No wonder that the expression “stained reputation” is still in use.

In the colonial context, while keeping the Old World preoccupation with whiteness and purity, the sheet gained additional layers of meaning. Sheets produced from flax grown and worked by New England settlers in the 18th century, the homespun, the coarse and unbleached “honest” cloth, independent of imports from the tyrannical Britain, became the matter and the rhetoric of the new American revolutionary identity: rustic, self-reliant, proud and unspoiled by excesses of industrialization. Homespun cloth, even if sun-bleached, was not really white; rather it displayed the natural beige to greyish shades of the flax fiber. That was the new purity: economic independence.8

Until the beginning of the 19th century the majority of bed linen was, as its name suggests, linen textiles. Since then cotton appeared as the most prominent material in bedding, and so it remains in our time. From the cotton boom of the 1780s and until the Civil War in 1861, raw cotton became the largest and most successful industry in the USA, one that made it an international economic power. The emergence of this power was conditioned on the abundance of labor—enslaved African people, a seemingly endless expanse of expropriated lands and readily available credit.9 The Old World textile industry, Britain’s largest of all, craved the “white gold” to expand its operations. The whiteness of cotton sheets thus bears witness to the horrors of slavery, the displacement of Native American peoples and devastation of land, and to the emergence of societal consensus that economic growth necessitates and justifies coercion. The genesis of white supremacy and race theory brought into being the pseudoscientific worldviews that morally sustained all the above. Many white pillow cases were transformed into Ku Klux Klan headgear.10

The trousseaus swelled in the 19th century as the middle class was eager to make an impression and enjoy the plenitude of the industrial revolution. The department store replaced the linen maid. Mass consumerism, new technologies, and new catastrophes all transformed how we see ourselves and communicate the ways we sleep and furnish and care for our sleeping place, the bed. The trousseau chest now is mostly gone and, apart from occasional seizures of nostalgia, there is no need to mourn its departure. After World War II, the “white linen civilization,” with its immense skill, dedication, and enslavement, met its demise (though this does not mean that the enslavement was not transferred somewhere else, to someone else.)

Bed linen is rarely white anymore. Industrial print technologies firmly took center stage at the mass market of the global bed linen industry: color and pattern, and then more of it. Do you remember that once it was news to be able to assemble your set of linens from differently designed elements? With antibacterial fabrics? It was not even that long ago when it was still remarkable to have access to a washing machine every day. An array of new materials appeared—those stretchy sheets do not need ironing. Technological developments were meant to relieve you of duty, eliminate the chore of straightening something that is destined to get wrinkled and creased. Here they do not iron bed linen, you know—it has polyester in it. Do you iron your sheets? Who are you?

Discipline, attention, care, affection, memory: all at very close range. If you have ever been between ironed sheets, you know. Nothing else feels this way on your skin and also addresses your nostrils with an unmistakable scent. What does it signify for you? Welcome relaxation, or anxious not-belonging? Remember Huckleberry Finn in search of a friendly stain in the all-too-clean bed of the good widow in the pocket paperback by Mark Twain? Remember the hidden tears of Paul D when he first slept on white cotton sheets in the devastating pages of Toni Morrison’s Beloved? Bed linen contains in its folds our memories, as well as memories we learned of, we read about. We are complicit in our bedtime reading, as we are in the contents of our armoires.

In Latin the verb complicare is formed by combining com- (meaning “with,” “together,” or “jointly”) and plicare, “to fold.” Its English descendant, complicit, literally means “folded together,” while figuratively it is defined as aiding in a crime. Plicare has also lent its first three letters to all the pliability in the English language. To ply, to twist together fibers, is to form a yarn, one to be woven into a sheet, a soft and structured stuff, pliable enough to be folded into a neat stack, especially when the violence of a hot iron is enlisted. A close relative of both complicity and pliability, implication shares the same Latin genealogy, conjuring up a vivid and thoroughly textile image of persons folded closely together like a stack of ironed and folded bed sheets. Pliable, adaptable: we hardly ever argue with iron, we find a way, we com-ply. Iron operates on condition of pliability.

Implicated subject, as cultural theorist Michael Rothenberg suggests,11 is a complex (yet again, plicare is im-plied and redirects to even older Proto-Indo-European root pel, the mother of all folding and braiding) position of persons “folded” into histories and structures of violence and exploitation: the successors and the perpetuators, willing or unwilling, direct or circumstantial. Hardly anyone can escape the ever-expanding and vibrating web of implication. Our positions as subjects are always multiple: we can be victimized in one regard, yet nevertheless perpetuators or benefactors of victimization of others in another.

The cheaper our sheets and pillowcases become, the more cotton and petroleum-based polyester is thrown into their manufacture, the more colorants are injected to print their designs, the more fuel is poured to ship them to us, the more fiber-infested laundry water and detergent are washed down our drains, the more mixed-fiber unrecyclable sheets are thrown into landfill, the more closely we are plied and twisted into the web of implication in violence, injustice, and exploitation of people and other living beings both contemporary and historical.

Counting time while worshiping speed and holding inactivity in contempt, industrialization in its most perverse and cruel manifestations—from the cotton plantation in the American antebellum South to the continent-wide Soviet gulag—promulgated a perception that reduces a person or a living being to their productive function, and in this, dehumanizes and inanimates them. Humans, animals, plants, waters and lands become “resources.” This pervasive perception has become mainstream. We are its perpetuators.

Slavery was abolished in the United States a century and a half ago, but its legacy persists in racism, and cotton, the unassailable king of natural fibers in the textile industry, still demands forced labor, sweatshop conditions, exhaustion of land, and waste of water in many places in the world. It is a difficult awareness to bear, and one haunting enough to chase the sleep spirit out of your bed for a long time. Still, awareness counts, and when we sleep at least we inflict less damage.

This series addresses the complexity of human sleep and its material attendants by seeking diverse local voices of artists, writers, and cultural activists to capture the contemporary, urgent, and immediate state of sleeping and being in bed, offering reflections on recent experiences, creative processes, stories, histories, and dreams. Each participant was commissioned to write a short, open-format piece loosely themed around dreams and beds. Although we cannot promise that the series will render the sleep of our readers more peaceful, we hope that it will enliven the significance of being in bed and offer an ever-slight opening to envisage alternatives to the frenzied, glorified rallies of sleepless productivity—to take a break, to reflect, to dream.