Dreams All the Way Down: On Sight Between

Mind, matter, dreams, and worldhood in Michal Sagar's solo exhibition

There are no light sensitive cells where our optical nerves connect to our retinas. Our minds create images to complete our visual field, clone stamping in real time, fabricating reality with the same neural mechanism that visualizes our dreams. Our optical nerves are about 1.6mm in diameter, a tiny perceptual hole in our window onto reality. But on the scale of humanity, when all blind spots are added together, that void becomes 200,000 square feet, capable of swallowing an entire city block. The void is as much a space of emptiness and loss as it is of genesis and entanglement, for into these gaps, we project dreams, hopes, desires, feelings, anxieties, imaginations. Michal Sagar’s exhibition Sight Between, currently on view at Form + Content in Minneapolis, engages and occupies the void as an interstitial site between mind, matter, dreams, and worldhood.

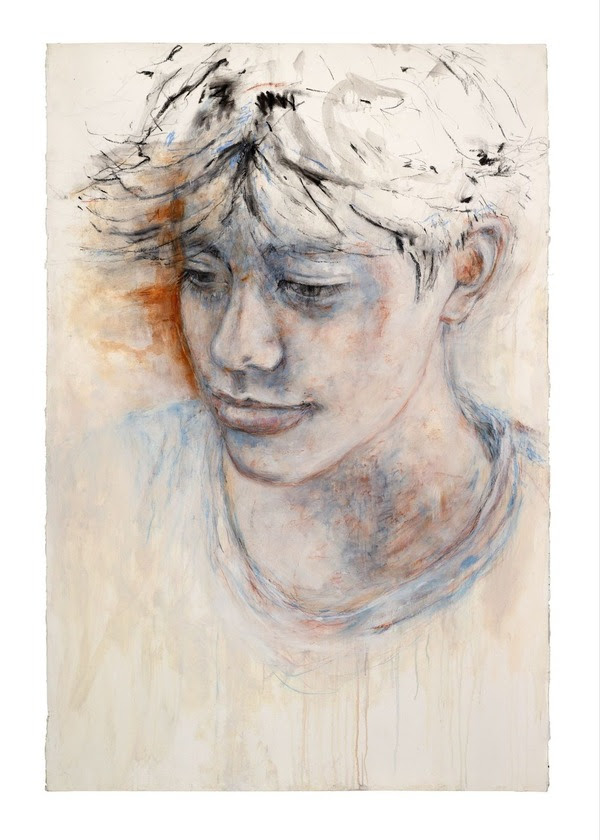

The exhibition opens on a portrait. Thirteen depicts a young boy, his head larger than life, staring down across the page as if lost in thought. Layers of grays, blues, and burnt oranges build the image, which appears both solid and tentative. Ghostly marks surround the boy’s head in gentle vibration, the image resolving like a watery reflection in slowly ceasing ripples. Black lines—at times as gossamer as a spider’s web, at others as bold and jagged as a mountain’s crest—stabilize the image without fully rendering the form: the drawing, like its referent, are both in the process of becoming. Thirteen is an age of in-betweens: not a child, yet not an adult, playful and hopeful, structured yet malleable, becoming a world unto oneself. Michal Sagar was my high school art teacher and first taught me after I had just turned fourteen. Seeing Thirteen, I immediately recognized the marks on the paper, the curve of the cheekbone, the feathering and mixing colors from lessons with Sagar twenty years ago. I recognize my teenage self, not in the image of the boy, but in the marks made on the surface of the paper. This experience of the work is predicated on my connection to Sagar, but more than this personal familiarity, I recognize in Thirteen the naivete, softness, playfulness, and the in-betweenness of my own students now that I too teach high school. Perhaps being in-between is not merely to be on the threshold of transition, but to experience a sense shared by multiple people across multiple points in time. Sagar draws this youthful boy with the insight of a teacher, capturing him on the precipice of change. While the model was her grandson, the boy represents a universal, his rendering left incomplete, capturing the multitude of paths he might take as experience continues to fill in who he is. Each of us is a black hole, a convergence of past, present and future, of patterns of behavior, connecting us to our deepest ancestors, to one another, and to the people we become.

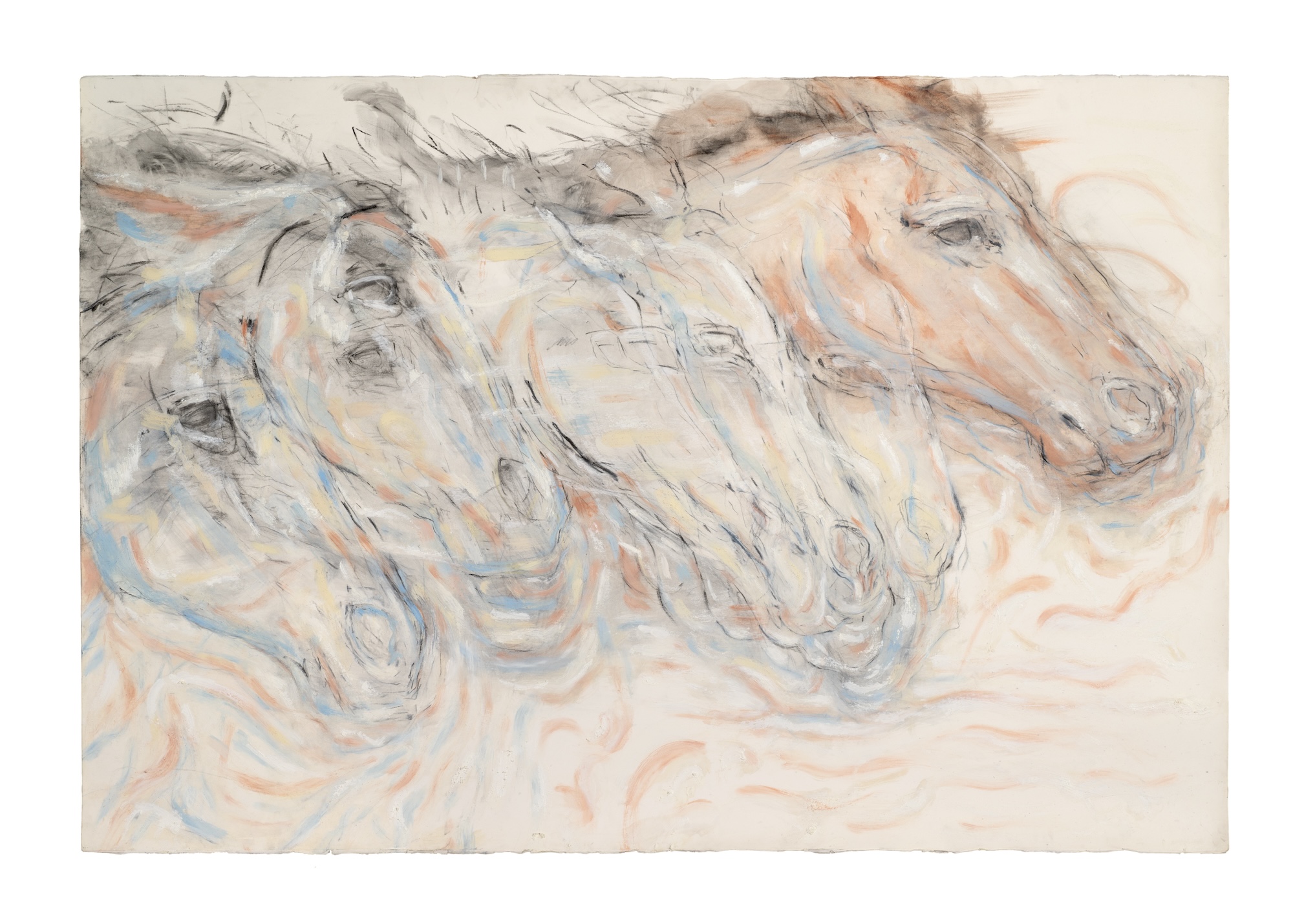

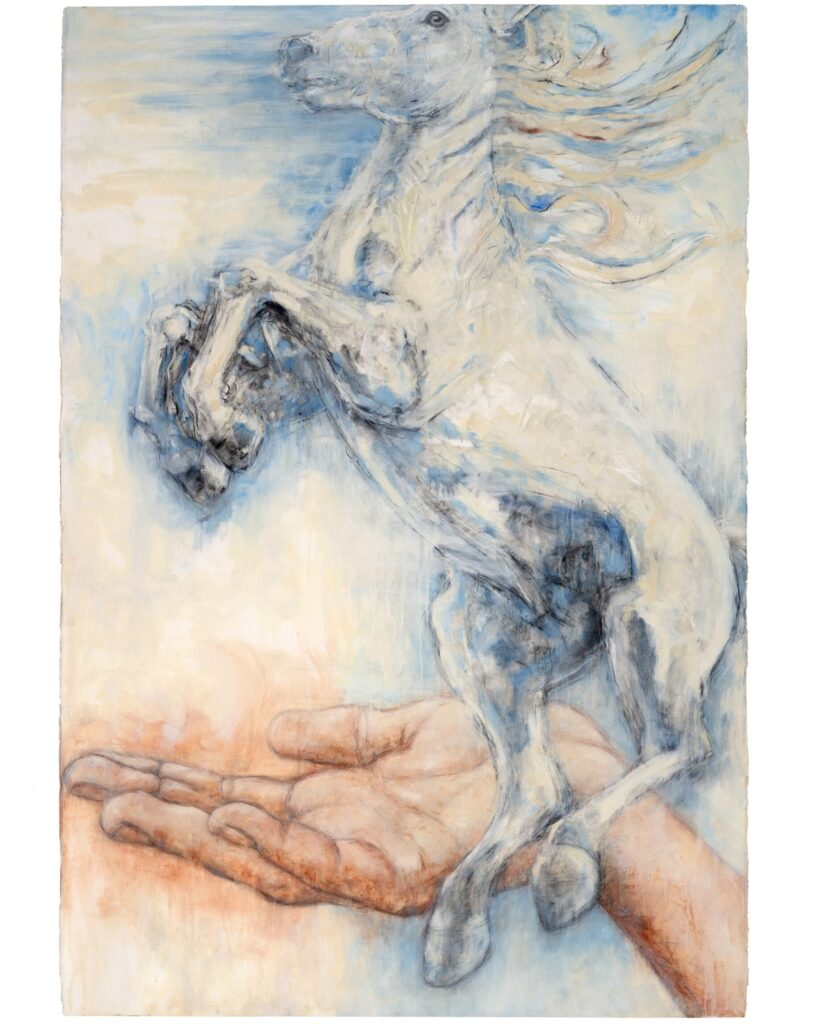

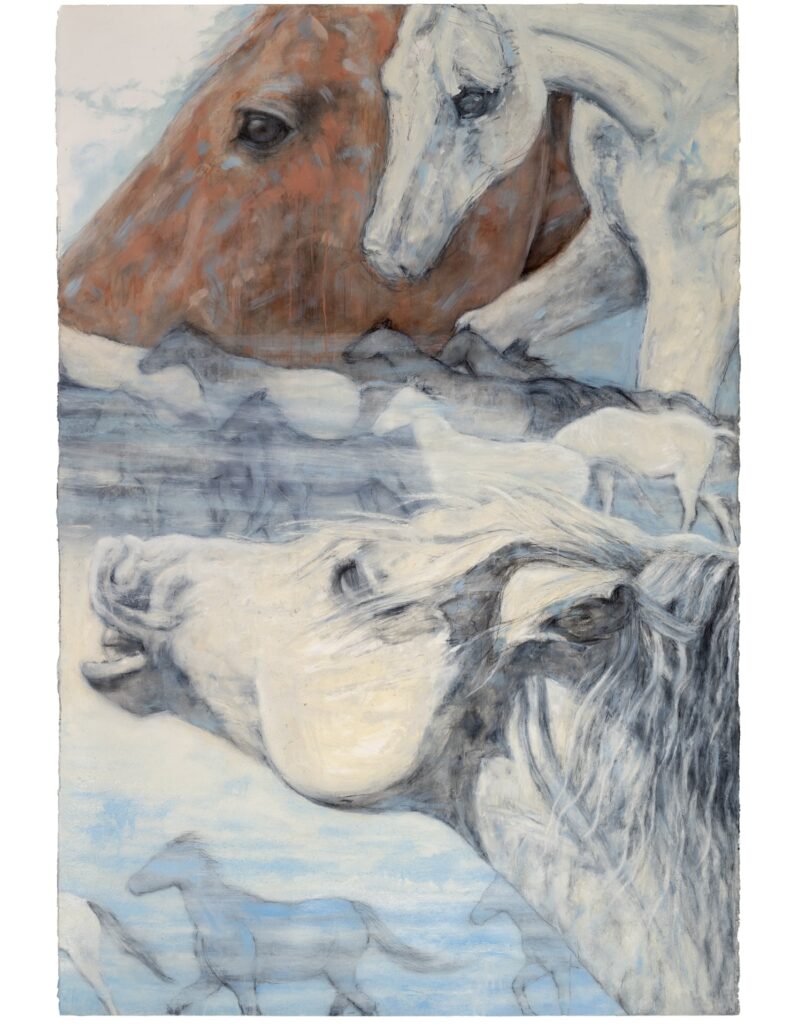

If Wishes Were Horses and And Wishes Were Horses, continue a similar stylistic approach to representation, though they are more complete than Thirteen. The horses in both works are rendered in layers, every mark searching the void for a form, building the image in sedimentary gestures. Despite their vertical orientation, both works feel cinematic in how they capture space, scale, and movement. And Wishes Were Horses, in particular, feels like a montage, a community of horses migrating through a placeless ether, capturing motion and the passing of time. Materially, these images feel the most built up, textured with thick globs of paint, sand and pumice, marks obscuring marks obscuring marks. If this show is a descent into a black hole, perhaps these works are a concretion disk where matter accumulates before falling into the abyss. So too, is this where we, as viewers, begin to spiral inwards. Up close, secondary layers of marks in the texture of the work rather than in the image itself build a richness of abstraction, filling the image with a microcosm of gestures. In If Wishes Were Horses, I can see Sagar’s finger dragging a path through texture like a prehistoric artist making a line in the dirt. The sandy surface and simplified form of the smaller horses in And Wishes Were Horses, bring to mind the 40,000 year old paintings in Lascaux Cave, which Werner Herzog described as forgotten dreams. These works capture something of dreaming: vivid impressions, often illogical but deeply felt. To dream is to be as free as a wild horse. And, if wishes were horses, then wishes have a will of their own, hopes and dreams galloping through the voids in our mind and our bloodlines, errant gestures connecting past to future.

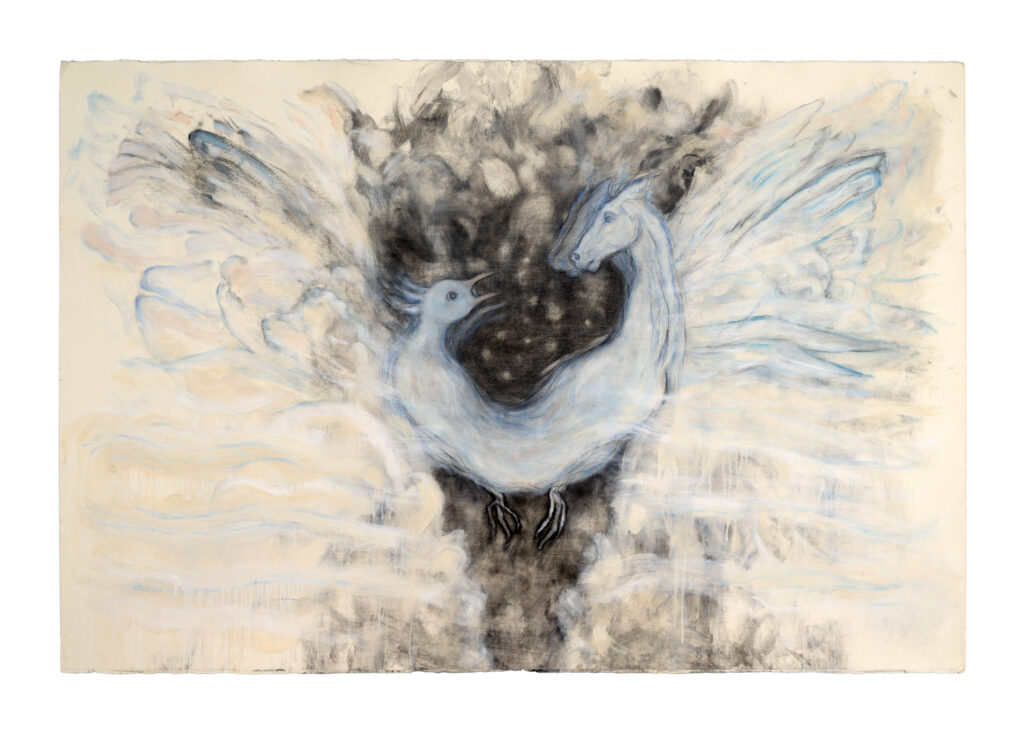

Across all six works on paper, Sagar’s material strategies stay consistent, employing graphite, charcoal, conte, pastel, sand, pumice, wax, and oil paint. However, on the opposite of the gallery wall from the three works discussed above, the imagery blurs deeper into the void, into the abstraction of absence and genesis. Between the Dream recalls the Futurist aesthetic of a body in motion, but rather than the industrial fascism of Marinetti or Pannaggi, here the repeating forms are organic, dissolving into cascading gestures, like a reflection fractured by ripples. This recurring metaphor of a reflection in water is more than a useful conceit in this review: it—like Sagar’s dreamy imagery—suggests that reality is fluid, undulating as perspectives come into contact with each other, as the world of dreams becomes entangled in the physical matter of spacetime. Memory of Flight is the most overtly fantastical of the works on paper. At the center, a horse’s head, neck, and shoulders merge into the body of a bird at its tail. The two heads look at each other, their shared body and legs perched between two jagged walls, a fissure opening onto the void. Humans, horses, and birds share a common ancestor in a reptile-like Amniote 300 million years ago, which carried the potential to both gallop across fields and to fly through the skies. The title of this work seems to ask if we can dream our way into the evolutionary memories of potential futures: Can we access memories that belong to something else? When horses gallop, tails and manes whipping in the wind, do they imagine themselves flying? Can a horse fly in its dreams the way we do? Can a bird gallop?

Between the Dream and Memory of Flight are sparse in their surfaces compared to the other works on paper. Without the thick layers of material and gesture, these images feel temporary, vulnerable to the passing of time. Dreams often are this way as well: I have woken up, my heart racing with the memory of a dream that felt so real, but as my body and mind reacclimate to my bedroom, the images and the stories I saw fall back into the void and I am left with an immaterial impression. By stripping back the materiality of these two drawings, Sagar invites us into the tentative fragility of a dream. But, a moment later, she jolts us out of this soft, and comforting dream by hanging In Sight, a drawing of two owls, above our heads.

Looking up at the sharp, watchful eyes of the owls, I am immediately grounded. Their eyes are penetrating, and yet Sagar’s gestural marks of white moving horizontally across the image make the owls feel stuck, as if secured to the wall. Their threat is defanged—and to emphasize this, Sagar has stripped the structure and detail from the owls’ claws in her stylization. Nonetheless we are being watched, their eyes following as we move. By placing In Sight above our heads, the exhibition space becomes a stage, and I become a performer watched by the art. This installational gesture feels particularly Lynchian, not only in the way Sagar’s imagery mirrors the enigmatic symbology of owls in Lynch’s “Twin Peaks,” but also in the way that the structure of the gallery manipulates our experience of the work by evoking unease. Sagar shared with me that she draws heavily from her dreams in conceptualizing the artwork, as does David Lynch. Sight Between follows dream logic in its narrative exploration, but where Lynch is situated alongside a subversive exploration of soap opera and small town America, Sagar’s work is aligned with late 19th century movements in Romanticism and Symbolism, entangling the representations of the natural world with emotion and mysticism as an expression of idealism.

The owls are not the only theatrical gesture in this exhibition. To tell the story of these drawings, I had to circumvent two sculptures installed in conversation with each other. In Mud God, seven vertebral ceramic cylinders hold a ceramic head 6 feet high, all prickling with texture sculpted by the artist’s hand. Ceramic shards surround the pillar, suggesting that the figure spontaneously rose from the mud as a momentary material manifestation of something beyond. Despite this power, there is a pathos about the god. His mouth hangs open, his skull is cracked, and he is hollow inside. Mud God is as eternal as matter itself, and his age weighs and wears on him. He is a god of absence and loss; his void is singular like a black hole. Mud God’s hollow gaze is fixed on Rain of Ephemera: an installation of ceramic shards, each the scale of a palm, suspended in the air by monofilament strings affixed to a net above. The gallery lighting reflects on the matrix of monofilament, causing the net to softly glow, a cloud on the horizon. This sculpture sits at the back of the gallery, and when I move behind it, the illusion of the object flips: I no longer see the ceramic shards as raining down; I see them as rising up, dematerializing and returning to the cloud. Rain of Ephemera is a scattered void, a web between matter, a god of entanglement and interconnection.

Each artwork in Sight Between tells a story; together they are a dream. The dream is Sagar’s, and much of it is opaque to us. But, often dreams are even opaque to the dreamer. Rather than representing the dream tautologically as in so much surrealist work, Sagar leads us through her subjectivity into a multifaceted meditation on time, space, and interconnectedness. The void acts not as the focus, but as a kind of language for approaching a metaphysical proposition: that mind is the primary substance of reality. Consciousness is primary and everything comes from it. To adapt a famous line by Carl Sagan: we are the universe dreaming itself. Every owl, every hoofbeat, every grain of sand and every brush stroke, every grandchild and grandparent, exists because of a dream.

Sight Between is on view at Form + Content Gallery through November 2, 2024. More info →