Please Touch the Art (As Directed)

Usually the rules of going to a gallery are simple: Dont touch anything, dont even get particularly close. But at the Walker Art Center's "The Living Years: Art after 1989," ways of seeing the art quickly get more complicated.

RECENTLY, I WANDERED through The Living Years: Art after 1989 exhibition at the Walker Art Center. The didactic describing Haegue Yang’s Series of Vulnerable Arrangement – The Blind Room invited me to enter and sit in chairs but also warned, “Please do not touch the objects on the table.” I was also invited to rearrange the bright laminated posters that make up Allen Ruppersberg’s As The Crow Flies/How I Miss the Avant-Garde. Other works are more traditionally protected. For instance, Katharina Fritsch’s plaster poodle is under glass, and it’s a good thing, too — I think I might not be able to resist petting it otherwise. But as I opened and closed the small metal drawers of Lutz Bacher’s In Memory of My Feelings — again, invited to do so by the the placard — I felt bad for the child being scolded for getting too close to the large round stone on the floor, looking very much like an abandoned and available toy. No doubt, that child wondered why I could I play with the art and he couldn’t. Usually the rules of going to a gallery are simple: Don’t touch anything, don’t even get particularly close. One time, I pointed too enthusiastically at a detail of Monet’s giant water lilies on display at Museum of Modern Art and was nearly asked to leave the building. The traditional rules are in place, for instance, with Cindy Sherman’s photographs on view now at the Walker, all of which are safely behind glass.

But with this art, apparently, things are a little more complicated.

As I toured the 1989 exhibition, checking the didactic panel on the wall to see what was and what was not allowed, I realized that this collection must make a particularly difficult job for the guards watching over all of us watchers. It’s worth pausing a moment to mention this particular realm of the contemporary art gallery experience — the somewhat uncomfortable fact of having someone watch over you as you try to experience the art; one quickly understands why most stores hide their surveillance cameras. And, for me, it’s hard not to let the ideas of the watcher dig into my subconscious, such that I’m never certain whether the guards are merely making sure I don’t touch the art and are not, somehow, also judging my reaction to it, or noting that I’m I not spending enough time in front of a one work or another. Regardless, I was visiting the Walker during a Free First Saturday, so there were many families exploring the galleries with me, and the guards were particularly busy with their primary job, protecting the art from enthusiastic kids. On a Tuesday afternoon, though, when I visited the show again, things were far less anxious in the galleries and the guards were interacting more with patrons, talking and answering questions. And one of them told me a show like this does, indeed, create more challenges for them than the average exhibition, since some pieces explicitly encourage interaction, while with most it’s still forbidden. If you want to break the tension of being scrutinized, ask one of the guards a question; turns out they are full of interesting information and ideas about the works they are protecting, and a discussion with a gallery monitor is always an insightful addition to the visit.

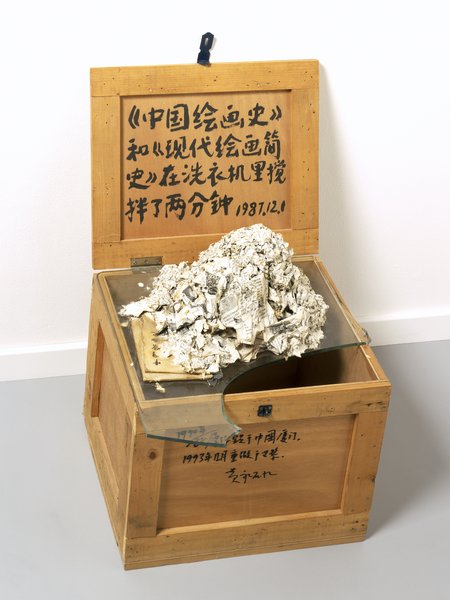

To make matters worse, as such, many of the forbidden pieces on display have a tempting, tactile, three dimensional aspect. For instance, Huang Yong Ping’s The History of Chinese Painting and the History of Modern Western Art Washed in the Washing Machine For Two Minutes is, in part, a pile of shredded paper. While I was looking at it, a child approached, hand outstretched, corralled by his father, who explained, “No touch.” Conceptually, Ping’s is a funny piece, a joke for grownups that depends on one’s ability to read the title and understand the iconoclastic act the pile of melted paper represents, and which also makes it possible for one to to read the warning not to touch it (fortunately, that’s what Dad is around for). I’m glad it is being protected so I could see it, so others can enjoy it, and in some ways the restraint we are asked to use with most of the pieces becomes simply another mode of engaging with the art.

______________________________________________________

When we can directly interact with the work, actually handle it, for a moment, the art becomes our life — what we are doing, not just something we’re thinking about or seeing over there.

______________________________________________________

Of course, as I say, generally a gallery is all restraint, but moving back and forth between our learned restraint and this idiosyncratic invited physical engagement is a fascinating aspect of the exhibition. The ability to touch the work, like a petting zoo for art, is clearly a contemporary trope, and Ann Hamilton’s recent installation, the event of a thread, at the Park Armory in NYC is an example of art as immersion in a fully interactive environment. But a visitor to the Walker exhibition learns that the rules are variable. You can’t interact willy-nilly, you have to read the instructions on the wall which outline how far you can go. But I think in doing so, all of the art becomes more tactile, even the objects of contemplation only to be taken in with the eye.

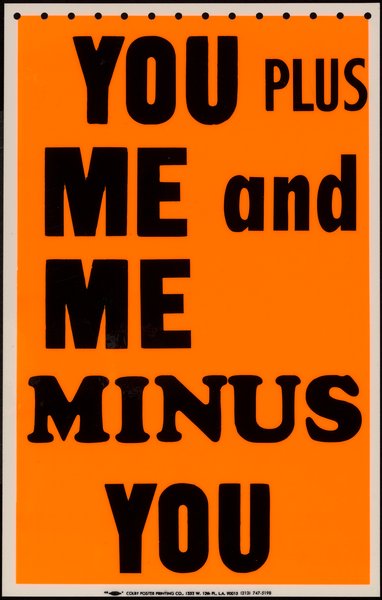

The exhibit takes the idea of interacting with art to its logical extreme with Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s untitled work: it’s a stack of prints, one of which you are invited to take. That’s right, you can bring it home and train puppies on it if you want, put it in a washing machine for two-minutes, shred it over your granola; it is yours to do with what you wish. This work, unlike the more traditionally protected, is guaranteed to disappear, that’s a part of what is supposed to happen with it. At least, its presence in the gallery will disappear; meanwhile, it will have migrated to who knows how many bedroom walls, basements and offices. Instead of a fleeting memory of seeing the piece, people will have the piece, or a part of it; the work of art is, itself, the original assembly of thousands of prints (several pallets of which, I am told, are in a Walker storeroom, hopefully enough to last the projected run of the show). This take-it-with-you approach made me wonder what it would be like if this was our tradition of going to a gallery; if rather than looking at Monet’s water lilies, we were instead expected to peel off a thumbnail of paint and take it home. For better or worse, the guards at MOMA, I’m sure, will never let us know.

And, of course, I’m glad for that. I don’t think you should be able to handle all art; and I don’t think the artists who invite us to do so are liberating art, necessarily. But these works do break a barrier usually separating us from the pieces we see in a gallery, and so they expand how art might function for us. Or rather, they invoke possibilities which have always been there and bring them to our attention, inviting questions: Is what’s on your kitchen table art? What happens when you rearrange the ads in a newspaper? Where does “art” begin and where does it end? That’s something I like about work we can interact with; for a moment, the art becomes our life, what we are doing, not just something we’re thinking about or seeing over there; such intimacy with the work gives us a way to reconsider artwork we’re usually instructed to keep a safe distance from and what happens when the rules change.

Noted exhibition details:

The Living Years: Art after 1989 is on view through 2014 at the Walker Art Center.

Jay Orff is a writer living in Minneapolis. His writing has appeared in Rain Taxi, Reed and Harper’s.