New York Hodgy Podgy

New Yorks jazz scene is bathed in a nostalgic light so soulful and evocative that the storied past those musicians inhabit feels immediatelike, if you could just get yourself there, you might run into John Coltrane on the street.

I DON’T HAVE A SINGLE TOPIC ON MY MIND RIGHT NOW. The weather pattern is stuck and, it seems, so is the cultural climate. Probably, it’s my own mind that is stuck in a rut. Never mind why: the fact is I don’t have an overarching theme for you this time, just thoughts that seem to rattle around and go nowhere. Maybe putting them out into the public ether will exorcise them.

I just got back from New York and, as often is the case, it’s got me thinking about the past. The timelessness of the city always makes me nostalgic. New York seems so relentlessly 20th century. It seems institutional and surprisingly parochial. It seems – no, it is rich. And rich places, like the rich themselves, prefer to stay the same, to preserve that sense of relevance that comes from being at the center of things — and they have the resources to do so. (“Hey, what’s that over there? A whole country to write my life on? No thanks, I’ll stay here because I am here and so are you…”)

I find myself wondering how such a deliberately exclusive place can really offer the kind of innovation and personal risk necessary to refresh the culture. Maybe that’s why there are so many Gap stores and Old Navys in New York. Only a sure thing can afford to take up residence there. I know, of course, this hugely reductive, and that it doesn’t characterize all that’s happening in New York.

All the same, I can’t help but think about the past when I think about the city.

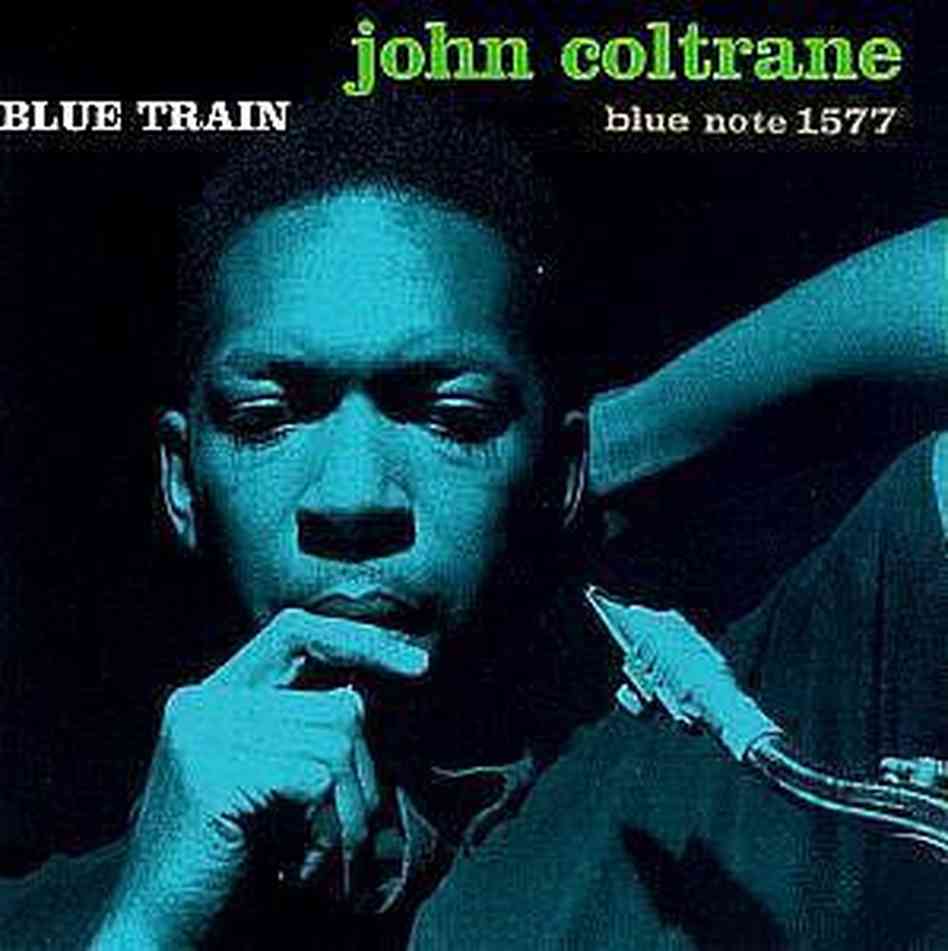

I grew up watching Woody Allen movies. I loved the Steiglitz photos. I knew the subway maps before I ever set foot on the 1 train. Then there’s the music, the jazz music: all those photos and stories, anecdotes and music rooms. And the musicians — all of them bathed in a nostalgic light so soulful and evocative that the storied past they inhabit feels immediate, like it might yet be yours, too. Like, if you could just get yourself to New York, you might run into John Coltrane on the street.

Of course, the past isn’t dead — it’s not even past, to paraphrase Faulkner. So, while I don’t want to get lost in reverie (or, worse yet, consign a vital art form to mothballs and fixed rules), what I’m saying is there’s a wonderful feeling of continuity in New York. Being a jazz musician there makes me feel a little less like a sore thumb and a little more like I’m part of some living, continuous stream of art. Walking those same streets as John Coltrane is comforting. And, anyway, it wasn’t so very long ago he was playing those New York City rooms. Only in America is 50 years a long time, even if the Half Note is a sandwich shop now.

____________________________________________________

The city’s jazz scene is bathed in a nostalgic light so soulful and evocative that the storied past those musicians inhabit feels immediate — like, if you could just get yourself to New York, you might run into John Coltrane on the street.

____________________________________________________

Another thing: it is great news that Minnesota Orchestra has reached an end of it stalemate. I am very glad that we once again have two great orchestras, and it is heartening that tickets have been selling so fast. But it’s not surprising, really. We have a sort of unassailable veneration for European classical music in America. And Terry Teachout’s new biography of Duke Ellington got me thinking: why is it so outrageous that an orchestra might disappear but, other than a few news items and a few weekends of full houses, the closing of a place like the Artists’ Quarter is little more than a blip? Such venues for new music are just as important to our cities’ cultural health, and a club like the AQ could have been saved for a fraction of the cost of a single orchestra season. There has been some suggestion out there that I’m arguing for some kind of bailout for jazz, that I want some of the money that large artistic institutions enjoy. (Which I do — I am not a fool. Of course I would prefer to see jazz musicians make a living, rather than just beer money, from the their gigs). But mine is an honest question, truly: why is it that we are so much more amenable to funding the old world’s music than our own?

Teachout spends a great deal of ink in his biography arguing that Duke simply couldn’t unlock the full mysteries of form that Mahler did, or Wagner, and that therefore he was unable to gain the sort of acclaim and legitimacy as those composers enjoyed. Teachout concedes that Ellington was uninterested European forms of music, but I think his framing of the argument gives us a clue as to jazz’s marginalized status in American high culture. Maybe we don’t support jazz the way we support the Minnesota Orchestra because we assess jazz according to a paradigm drawn from the canon of European music. But in so doing, we’re measuring our own music against a form that, no matter the similarities, has fundamentally different roots, alien concerns and modes of development. As a culture, we still don’t know how to deal with jazz on its own terms. We don’t understand it as an independent form, and so aren’t giving it a fair shake.

Maybe we’re more comfortable waxing nostalgic about the music, because jazz makes such a compelling early to mid-century set piece; the black and white photos and two color LP covers are beautiful. I don’t know. I am good at questions, but not so good at answers. Maybe there will come a day when the tired old questions give way, and Ellington won’t be judged against Mahler but according to the measures of his own musical form. And maybe someday, the tired old question of why we fund others’ music before our own will be moot too.

____________________________________________________

About the author: Jeremy Walker (known to many as “Boot”) is a prolific composer and pianist who started playing the saxophone at age ten in Minneapolis. In 2005, illness (recently diagnosed as late stages Lyme disease) forced Walker to stop playing the saxophone; he turned to piano and composition earning accolades including a Jerome Foundation Travel/Study grant and collaborations with Alvin Ailey alumni, TU Dance, and Zenon Dance Company. He has performed with Vincent Gardner, Marcus Printup, Ted Nash (all with Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra); Wessell “Warmdaddy” Anderson (Wynton Marsalis), Anthony Cox (Stan Getz, Joe Lovano), Ron Miles (Bill Frisell), Matt Wilson (Dewey Redman and Jazz at Lincoln Center) and other notable musicians. After some years living in New York, Walker moved back to Minneapolis in 2012 to be close to his son, Sam. This March, Walker is releasing 7 PSALMS, a suite for solo voice, choir, saxophone, piano, bass, and drums. The CD release concert is it at Benson Great Hall on April 11, 2014. More information here and at www.boot-music.com.