“I Am Desperate”: Some Notes on Institutional Violence

Sculptor, architect, and interdisciplinary artist Pedram Baldari denounces the structural factors that devalue the labor of “artists and educators”, with special attention to the precarity of adjunct faculty, the inequality of institutions, and what happens when the value of people’s existence is measured by their achievement.

Among artists, when asked to define what we do, one sentence often serves as a shorthand self-introduction: “I am an artist and an educator.” What an innocent sentence it is. It feels so natural as it comes out of one’s mouth, honorably indicating commitment to the complex task of education of art in cultural institutions. In truth, the friendly sentence, “I am an artist and educator,” masks a stringent class system.

People from different classes in the arts may socialize, be friendly if not friends, embrace progressive politics, and espouse rigorous critiques of capitalism and meritocracy. But what becomes hard to ignore when an adjunct lecturer hangs out with a fully tenured professor is this: we simply live in different realities. One group is always in need of the other’s support and recognition; one group has no say at the table of power where the other one sits. Upper-class problems are the lower class’s dreams. The circle of artists and makers is like society at large, even though it wants to pretend otherwise. Perhaps one group is more invested in maintaining the façade. But sometimes, cracks do appear.

Recently, talking with a fully tenured R1 university professor in the visual arts, the conversation turned to an artist we both know. The professor noted that, obviously, said artist is “desperate”—because they are doing all they can, having as many shows as they can, and committed to accepting any adjunct lecturer position with the hope of landing somewhere “more secure.”

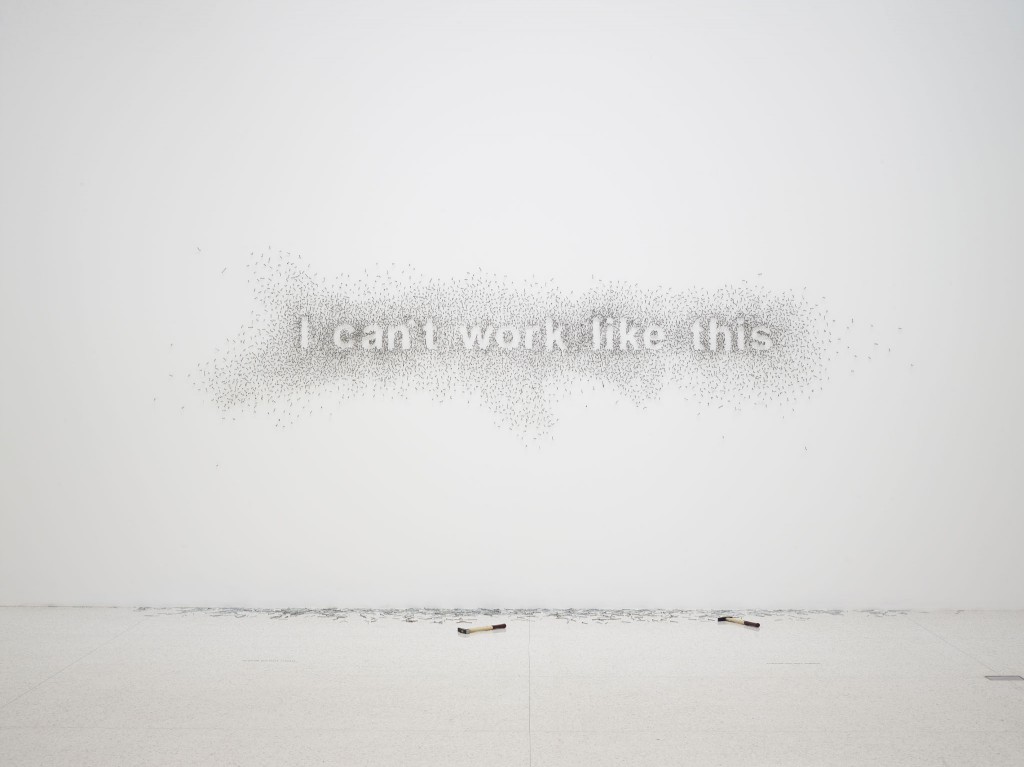

Desperate. I felt for a second that I had been struck by lightning.

I too participate in many art exhibitions. I am working low-income academic jobs, and at the same time pay visa fees and lawyer fees to stay in the country—and in academia. What I have paid in visa fees in the past few years has consumed more than half the income I have earned. I am the definition of desperate to a colleague who seemingly works in the same field, but belongs to a completely different reality. We are separated through the distinction that institutions impose upon our existence based on the evaluation of our achievements through a specific lens, a lens that translates to the level of desperation in our professional conduct. The more desperate we are, the more exploitable we become. Perhaps it is in fact the visibility, intensity, and quality of the institutional violence used against the most tenuously employed that can categorize academia into different degrees of desperation.

It is an obvious fact that starting jobs, in any field, can start with lower payment. But how much lower is low enough to still float a person on the surface? The reality is that most part-time adjunct lecturer positions have no benefits, while they do most of the heavy lifting in academia. An adjunct lecturer can work in the same capacity as a tenure-track or tenured faculty member but get paid less than half for their labor. While academia argues that adjuncts have to meet no research requirements, the reality is they actually have to fund and conduct research in a rigorous fashion in order to one day finally land a job that offers benefits or better wages.

Most artists who are part of this precariat of the temporarily employed go through different waves of “desperation.” While academia wants them to picture and portray to students a utopian prospect of the arts as a profession, the institution violates almost every aspect of basic employment rights a person should have. The question here becomes: what really separates adjunct lecturers from their colleagues, those chosen by the academy to become members of the exclusive, privileged group of humans/scholars/artists/cultural workers/professionals/educators?

Asking this question reveals another layer of violence that is not limited to work rights, benefits, or professional value, but becomes personal: the value of people’s existence is measured by their achievement. If those achievements can fit into a set category, then they can have healthcare benefits for themselves and their families. The system for such evaluation is rather arbitrary, especially when it comes to the arts and, more importantly, to defining levels of research in the arts by bureaucratic terminologies that don’t even apply to adjunct lecturers. Their research is discounted, not considered, and therefore it does not even matter how rigorous their research is; they are only valued for the classes they teach. That is it. They could be the greatest artist of our time and it doesn’t matter.

The institution here does not have any regard for the individual as a human being and their background, ethnicity, sexuality, immigration status, class, or history. The institution does not care that, if it is granting the privileges, it mostly grants them to those who already find themselves in a privileged socio-ethnic group. The institution doesn’t care if the violence it projects hits mostly those who are marginalized. This reality becomes acutely painful when the process of admitting someone from the margins into the exclusive circle is called “a diversity hire”: one’s qualities as a professional are diminished by one’s color of skin, immigration status, or sexual orientation. How can I not be desperate knowing these practices surround my field? How do I get rid of the bitter taste of any achievement when I am labeled a “diversity hire”?

I am desperate when working as much as three artists combined to compensate for all the sociopolitical, economic, and historical disadvantages I have. I carry them like a shell—not to be shed, as I draw my artistic narrative from them—but like a curse that I draw my energy from to fight for equality, or like an occupied homeland that I long to go back to, even though I know all the houses are demolished, trees burned, villages destroyed and songs forgotten. I won’t let them be forgotten, and I won’t let the demolished land stay barren forever. I am an artist in the first place because I used to lose sleep over the tales I needed to tell, the stories I suffered to recount, and the love to be spread. I also cannot abandon all the sacrifices I made to be here. I cannot forget the careers I deliberately abandoned to step into this art world.

I am a desperate Kurdish man living thousands and thousands of miles away from my beloved mountains, in exile only to do and make art, to teach the way I think about art, to see and use art as a major project to emancipate society. I am actively exposed to the power struggles and dynamics that brutally alienate people who have chosen to live the life of an artist, people who know the challenges and nonetheless try to scrape together the basics to continue. What connects me to thousands of artists in faraway countries is the universal issue artists are dealing with, regardless of whether they are in Tehran or Istanbul or in Berlin or L.A.: the idea of art as a means of emancipation. This is an idea strangled by eurocentric, institutional systems of legitimation on the one hand, and on the other hand, disarmed by city codes for studio operations, gentrification, and all the oppressive policies that turn this presumably class-fluid occupation/role/lifestyle/worldview/being into a well-regulated capitalist formation.

All the seemingly progressive concepts within the arts, such as urgency and relevance, pale in comparison to the questions raised by the physical size of an artist’s studio, professional connections, social class, and ethnicity. All that translates into access. All that is part of the body of the horrible monster that is violently feeding on the beautiful emancipatory art project. The monster defecates despair and deprivation of all kinds, and deforms the basic rights of those who have been violated into submission. Everything is woven into a web of desperation, resistance, and creativity in my reality as an artist and educator—to the point where it is not easy to even point out when the violence has ended and creativity started.

The questions left to think about are, first, what is preventing a union of part-time lecturers in the arts, or artist workers and cultural laborers who work day in and day out in all kinds of spaces, from posh artsy hybrids to more defined cultural spaces? I believe we are at a pivotal moment in our history to create alliances from the different points of the spectrum. We should be able to think how women’s movements across the globe couldn’t move forward without men helping, how undoing racial disparities in the U.S. could not progress without white people helping, and how immigrants would not be able to breathe if citizens didn’t help.

I think as “artists and educators” we have to come together and create an atmosphere where tenured faculty do not diagnose degrees of desperation among the less fortunate, but can step up as allies and advocates. Institutions do not change on their own; they are changed by those who wield the institutional power within them.

Second, why is it that artists as a social group have always been exempt from being considered an occupation? Nothing is expected to be free or cheap these days, but when it comes to an artist, exhibitions are expected to happen free of charge, while the drinks people buy during the opening are not. The person who serves drinks gets tipped, but the artists who have spent months and years and decades making and working and creating have to put their work up for free. This system adheres to the old idea that artists can always sell their work, but in how many of the many local or regional or even lavish international shows have you have witnessed works being bought by people?

While we bring the vibrant scene to such-and-such a city, what does the city do for the artists? Allowing more “artist lofts” to be built where the cost of living is prohibitive for artists? When is the time for us to answer to the sentence, “It is good for your resume,” with, “Thank you, but it is not paying my bills,” or, “It does not provide the ongoing rent of my studio.” Why do we abide by the paradox of doing things for free and yet being measured by the standards of capitalism? Why are most artists still willing to support the economy of studio spaces, even though this economy has zero regard for the hardships that an artist has to go through to maintain their artistic practice? A budget that could go to savings, food, and healthcare has to turn into rent and utilities in order to uphold a space that is the very image of oppression of artists. While the slogan, “Creativity has no price,” has been the downfall of any attempt to create a minimum wage in our labor, why do we have to participate in exhibitions that put everything on the artists, from shipping costs to installation? In the case of a sale, the gallery is entitled to 30-50%. These models have to change and be resisted. We have had enough.

Still, we are left with no choice but to participate in this broken system. We fill out hundreds of job applications and vie for museum jobs, we pay to be considered for grants and artist residencies, we mount free exhibitions and pay to ship our work. We fund every aspect of the production, in order to somehow either one day be financially supported, or gather enough credentials to perhaps have a chance in our future endeavors. We are continuously being violated—intellectually, existentially, financially, creatively, and mentally—for being the members of society who give life to commonality, collective stories, myths, beauty, music, fantasy, imagination, love, openness, and the praxis of resourcefulness and out-of-the-box thinking.

We have to rethink the models in which we are accredited, qualified, organized, categorized, shown, featured, accepted, lectured, participated, cataloged, educated, employed, accommodated, facilitated, granted grants, and perceived. We cannot do it alone.

This article is part of the series by guest editor Christina Schmid