Institution as Living Artist, as Can Opener, as System Change

A conversation with Boris Oicherman, as he concludes five years as Curator for Creative Collaboration at the Weisman Art Museum: on supporting open-ended, cross-sector art projects and creating an arts ecosystem that is fundamentally collaborative

When Boris Oicherman asked me to help him take stock of his experiences at the arts job he was in the process of leaving, I gave him a writing assignment. The job is an unusual one—Curator for Creative Collaboration at the University of Minnesota’s Weisman Art Museum, established to support open-ended, cross-sector art projects—and I thought we might need more than a traditional interview to think through the lessons of the work. Over the course of his five-year tenure at the Weisman, Oicherman facilitated a rangy mix of projects involving over 50 artists, including collaborations that tested therapeutic creative writing practices for youth in crisis; brought scientists, artists, neighborhood residents, and railroad employees together to ask questions about the revitalization of polluted land; and explored strategies for shifting resources to incarcerated artists and cultivating alliances across prison walls. As observers increasingly call on arts institutions to step into more socially and politically engaged roles, there’s a lot to be learned from those who’ve already facilitated such projects—not simply to see what success looks like, but also to understand the difficulties inherent to the work.

When Oicherman and I sat down for the interview, he reflected on the tangled nature of those difficulties. They crop up at every part of the process of a socially engaged collaborative project: from conceiving and pitching an idea, to sustaining conversation across siloed sectors, to providing unconventional behind-the-scenes support, to convincing funders to give money to efforts that might never produce an art object or show. It can be a demoralizing reality to contemplate, and it was here that the writing assignment ultimately proved its supplemental value. Inspired by a Q&A with artist and curator Kristan Kennedy, the assignment uses the formula Institution as ____ to create a poetic, riffing list of roles for arts institutions to aspire to. Kennedy’s list imagined arts institutions as radical, mother, salad, shelter, and decanonizer; Oicherman’s called on them to become a living artist, living wage, and living beat. What I like about the exercise is the way it condenses the complexities of critiquing and transforming arts institutions into a register that is at once poetic and tangible. Shuffling through these possible roles makes it easier to keep in mind the big-picture stakes in play. As you read this interview, you might try the exercise yourself, imagining not just Institution as ____ but Artist as ____, Curator as ____, and Funder as ____, a whole ecosystem of different roles to aspire to in the slow, difficult work of pushing art to do and be more.

MIRANDA TRIMMIERI know you’ve done this a zillion times, but let’s start by talking about the Weisman’s Target Studio for Creative Collaboration. What was your job there?

BORIS OICHERMANThe institutional history begins with the Frank Gehry building, built in the 1990s, and with Lyndel King, who was the museum’s director for 40 years. Lyndel raised money to build the building and was thinking strategically about what the Weisman should do. And one of her ideas was that a university art museum should support artists working with university scholars. But it remained at this abstract level for many years. It took 20 years to get an addition built to house the program and another five years to raise money for the curator’s salary.

When I ran across the job description, the idea was still abstract: how wonderful it would be if artists collaborated with researchers at the university. With scientists, really, that’s what was implied. I was at the end of my MFA and was already disillusioned with the push for art-science collaborations, because artists are never treated as equals in them. What I ended up pursuing was a broader vision, where the goal was to help artists develop collaborations on their own terms, both within the university and beyond.

MTOne thing that seems difficult about this sort of program is that the outcomes aren’t necessarily visible to the public. The work is the thinking and the talking. You might never have a show. How did you define what makes a successful project? Talk about the shapes some of the collaborations took.

BOIt seems important to say: there are pretty much no failures. If the measure of success is less, “Oh, we had this wonderful exhibition,” and more “Oh, this project keeps developing and changing,” then most projects are a success at some level. I can look at projects that started five years ago, and they’re still running and still changing. One is a collaboration with the medical school. Four artists met four medical researchers with the idea that they spend a year having free, unrestricted conversations. In one project, the poet Yuko Taniguchi was connected with Kathryn Cullen, head of child psychiatry at the med school. Katie works with adolescents in crisis, and Yuko had been pursuing research with the Mayo Clinic psychiatry unit, trying to figure out how to bring creative writing into youth treatment. Their collaboration developed very fast—they had clinical work running within the first year.

Another project was with Peng Wu, who has a very deep socially engaged practice and came to me with this statement: “I have insomnia; I would love to talk to somebody who knows something about sleep.” So I connected him to a sleep researcher, and they talked about sleep as culture. When there’s a society that tells you when to sleep, where to sleep, with whom to sleep, with what furniture to sleep in—

MT“Healthy” sleeping or whatever.

BOWhat is healthy sleeping? When you don’t sleep, they give you a pill. It’s not like doctors are unaware of this. When Peng began working with the researcher, neurologist Michael Howell, the speed with which the conversation transitioned from “give me a pill” to the culture of sleep was mind-blowing. But the medical school didn’t have any way of using the work. Michael had a practice to run, research to conduct, and he was not empowered to do anything concrete with the insights. When the year ended, the conversation ended. Eventually Peng joined Yuko and Katie’s project.

By now, they’ve established a multi-year project to study creativity and mental health. They got an NEA grant and a quarter-million dollars from the university to do it, and the campus administrators at the University of Minnesota Rochester, where Yuko was working as a creative writing adjunct, were so inspired by the work they created an Art and Medicine tenure-track position for her. And the artists keep bringing questions to the process. How do we think about research in terms of justice? How do we conduct mental health research with communities whose mental health has historically been ignored? These social conversations have become part and parcel of their medical research, which is kind of the best thing I could have hoped for when I started five years ago.

Another example that comes to mind is Emily Baxter’s We Are All Criminals. It’s a multi-part project, and one phase involved working with artists incarcerated at Stillwater Prison. Most prison art projects involve taking art produced within a prison—often writing or drawing, because this requires minimal resources—out of prison and showcasing it in an exhibition. This project challenged that model. We curated collaborative teams where incarcerated artists were paired with Twin Cities artists to develop new work over a year. What emerges is a new model, where the museum facilitates work and access to resources across the prison walls.

MTThese projects are questioning disciplinary practices, but also intervening at a material, sector level— how institutions work.

BOLately I’ve been reading Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, a theorist of photography who writes about the imperial shutter. I press a button on the camera, and the shutter opens and closes, creating three degrees of separation. There is a temporal separation between before and after, between the moments when the photograph is taken; a spatial separation between here and there, between what’s behind the camera and what’s in front of it; and a social separation between us and them, between the worlds of the photographer and the photographed. Azoulay helps me think about the separations that are foundational to so many disciplines, institutions, and sectors. Unless collaboration challenges those separations, it’s not particularly meaningful.

MTFor me, the question of how colonial modes of knowledge persist is essential. The task of trying to undo those practices just a little bit and get traction in another kind of praxis is so enormous. But it’s a necessary part of any project if you’re trying not to reproduce the same old violence.

BOAnd recognizing this as violence is so important. Even just making the statement—that the systems which keep us working in separate buildings or prevent us from even meeting in the first place are violent—is important.

MTIt’s about constantly naming and denaturalizing these things. And it’s easy enough to say that in the space of a conversation like this, but to constantly do it in practice is much harder. To intervene in the many, many, daily ways that those structures persist—it’s much harder.

BOYou know that question that always comes up when there is a conversation about decolonization: “Okay, so what’s on the other side?” On the one hand, the question has a very colonial logic. “What’s the product? What’s the outcome?” But while the motivation for that question is often wrong, it’s not a meaningless question. What artists do is imagine realities that are not here. Imagination is an amazing and subversive tool.

When I ask myself what a decolonized world looks like, one thing I think is that, among many other fundamental changes, discipline will not exist. That isn’t the current institutional reality, but I can let it guide the way I imagine my work and make the decisions I have power over. I can set up a project so the fact that these two people are from different disciplines will not matter.

BodyCartography Project, The Place of Space, 2018. Courtesy Weisman Art Museum. Photo: Boris Oicherman.

Amoke Kubat, Black to the Future, 2020. Courtesy Weisman Art Museum. Photo: Boris Oicherman.

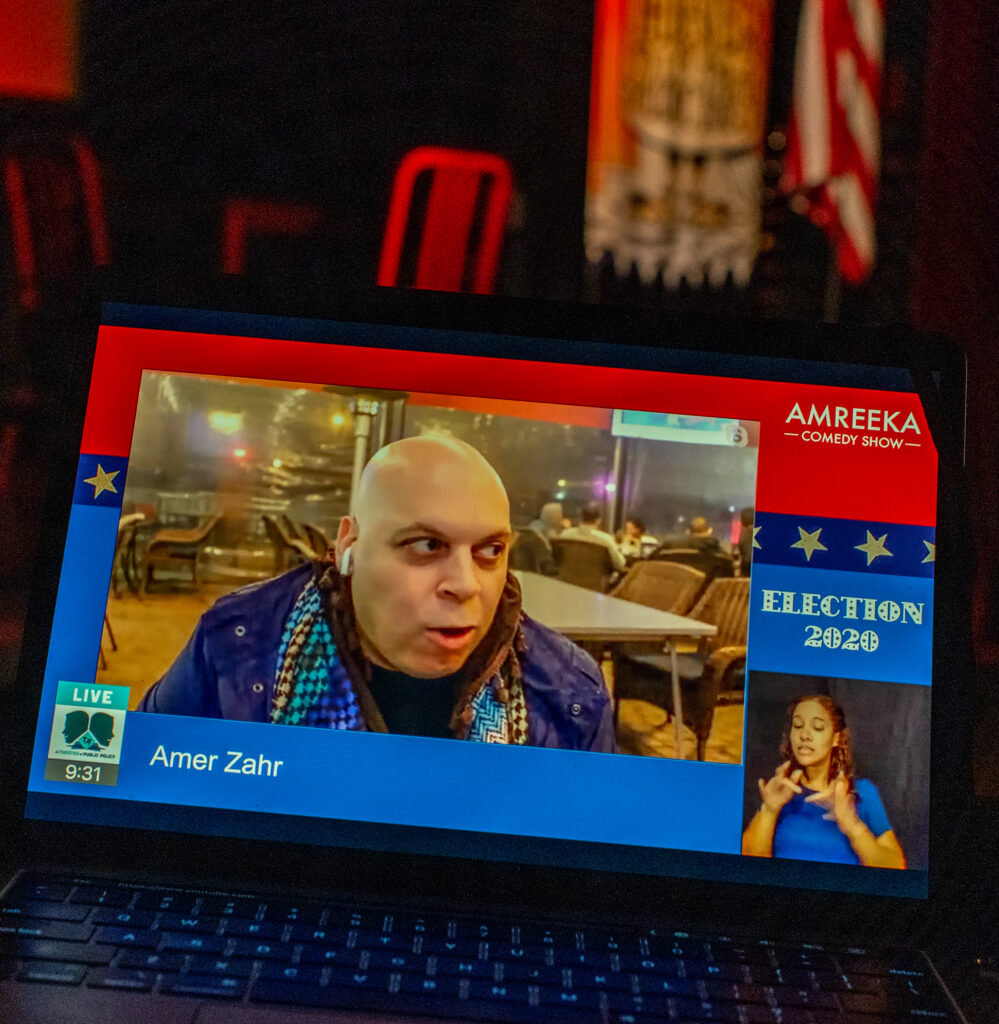

Wafaa Bilal, Amreeka in America: Election Night Comedy Special, 2020. Photo: Boris Oicherman.

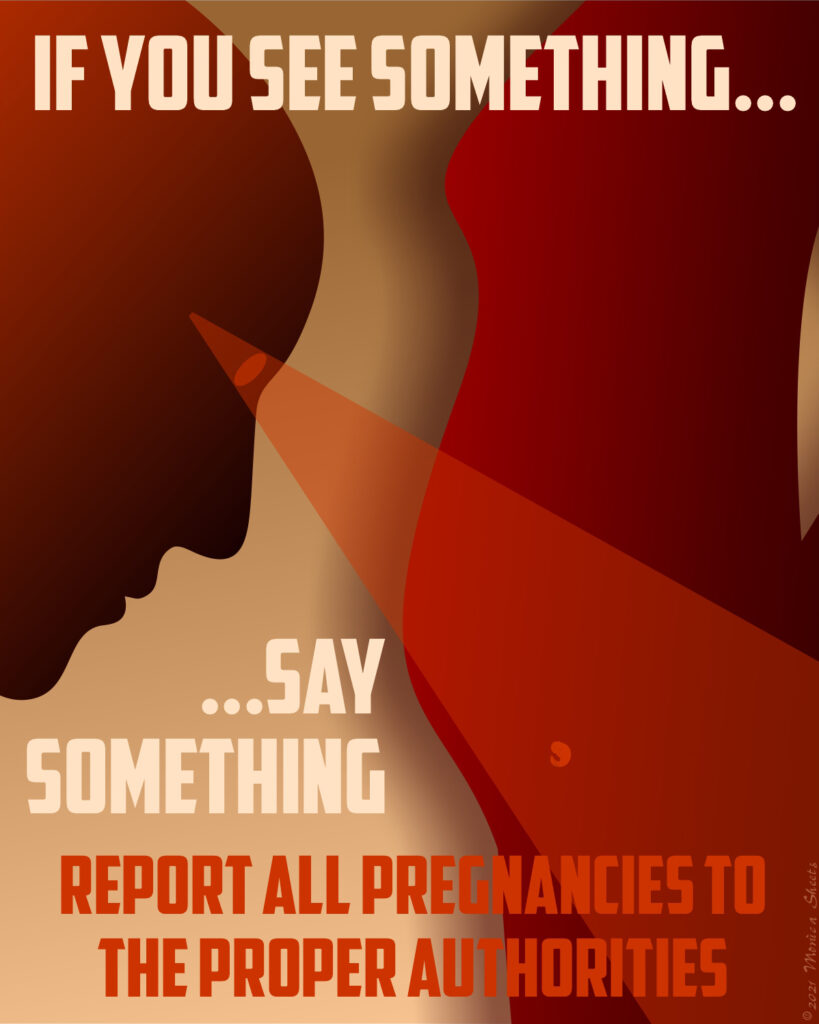

Monica Sheets, If You See Something…, 2021. Created for the series of artists’s responses to the Texas Senate Bill 8. Courtesy Weisman Art Museum.

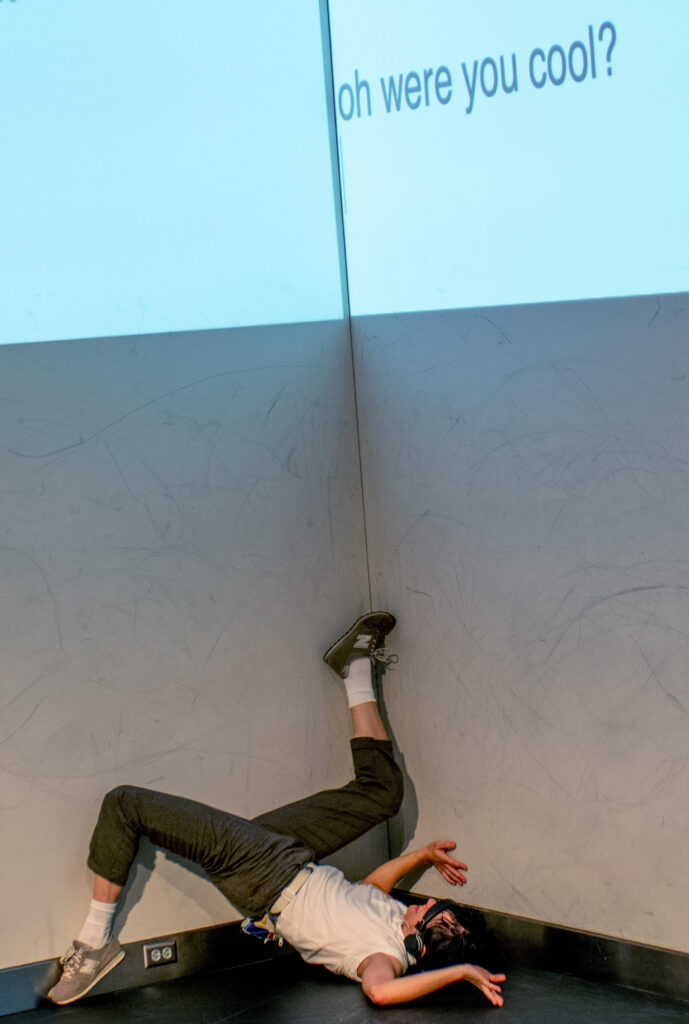

Marcus Young, Museum/Life, 2019. Pictured: artist Ricardo Beaird. Courtesy Weisman Art Museum. Photo: Boris Oicherman.

MTCan you say more about what it looks like to support these projects on the back end?

BOFor a curator, it begins with acknowledging that you are not there to create content. You’re there to create a supportive context, to point artists to the resources available through the university and then get out of the way. The artist’s job is to figure out how to use these resources. And it takes a certain kind of artist, by the way, to want to work like that.

MTWhat about the practical side of the work? I know what some of the behind-the-scenes stuff can look like, because I contributed to one of these projects [Gudrun Lock’s The Nature of Shoreham Yards, a research project at a truck and train site in Northeast Minneapolis, which included an exhibition at the Weisman]. So I know some of the forms the curating work took. You facilitated university grants. You showed up to meetings with Canadian Pacific, who owns the trainyard, and connected Gudrun to university lawyers when the company expressed interest in partnering on the project.

BOWell, again, all these things connect back to the understanding that as a curator I am there to create institutional infrastructure and point artists to university resources. Some resources are very tangible: a museum space for exhibitions, stipends, lawyers. Some resources are less tangible. The university’s institutional reputation can do a lot—this was one of the factors that convinced the Canadian Pacific to agree to the collaboration.

MTWhat were others at the Weisman doing to support this work? Again, with Gudrun’s project, I saw some of it. Her show was information-dense but also really committed to sparking public conversation. So there was a lot of extra interpretive work. Staff members interrupted their work to print off extra exhibit guides for class visits. Or student workers stationed themselves in the museum space to help explain pollution documents or bird surveys to museum-goers.

BOThe museum staff was extremely supportive of the Target Studio projects. And that wasn’t easy, because their jobs aren’t structured for it. The most contentious part of my tenure at the Weisman had to do with the emergent nature of the projects. Museums are designed to exhibit and acquire objects—to transport paintings or sculptures, to display them, to insure them, to advertise exhibitions in set promotional cycles. When you’re developing evolving projects with no fixed outcome, museums aren’t set up flexibly enough to support them.

Monica Sheets, Feminist Strip Club, 2019. Courtesy Weisman Art Museum. Photo: Boris Oicherman.

Anna Marie Shogren, Lifelong Choreographies, 2018. Courtesy Weisman Art Museum. Photo: Boris Oicherman.

Satu Jiwa Collaborative (Tasha Baron, Liz Draper, Nima Hafezieh, Munir Kahar, Drew Kellum, Maja Radovanlija) Isolate/Unite, 2021. Courtesy Weisman Art Museum. Photo: Boris Oicherman.

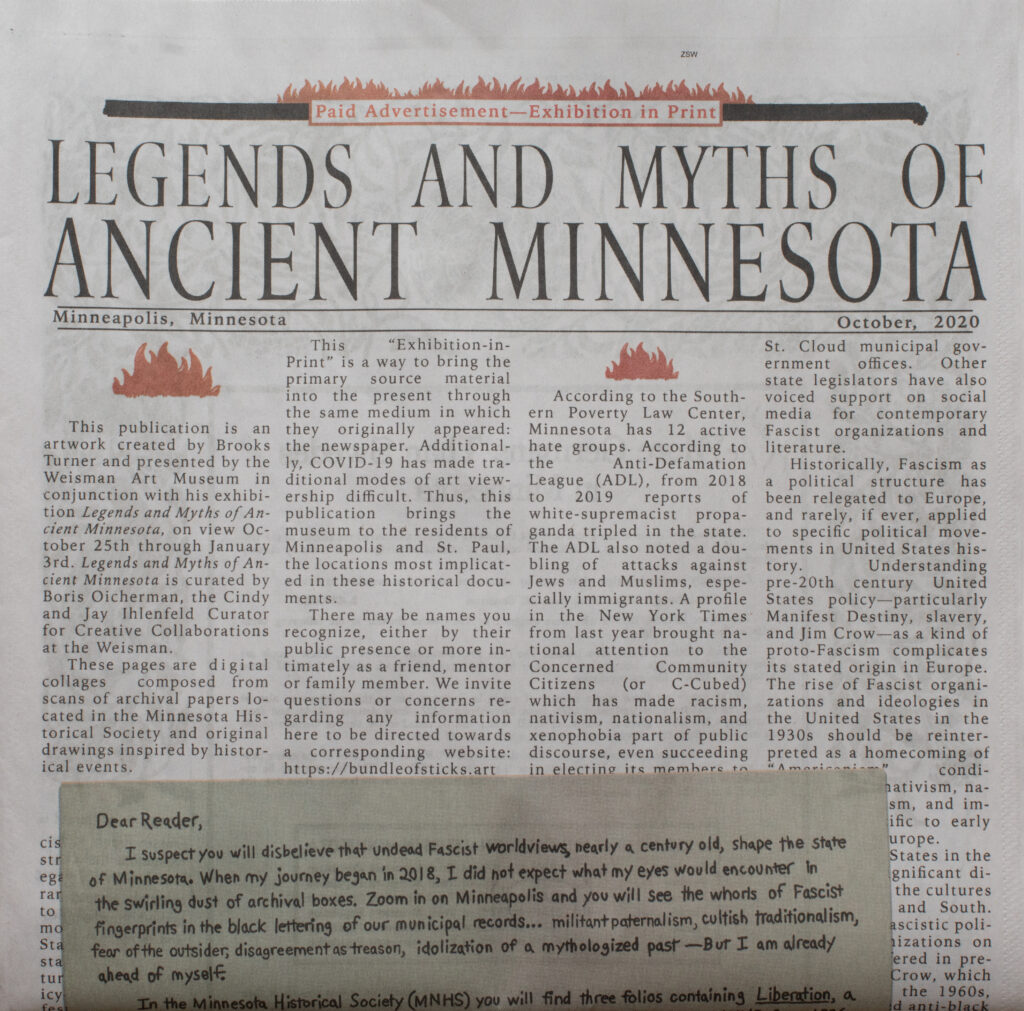

Brooks Turner, Legends and Myths of Ancient Minnesota, 2020. Courtesy Weisman Art Museum. Photo: Boris Oicherman.

Habitability Workshop, a mini-symposium on habitability of environments at the home of Boris Oicherman. In collaboration with the architecture group Interesting Tactics. Photo: Boris Oicherman.

MTOne thing that seems necessary is developing an institutional identity that’s articulated in terms of cross-sector collaborative work. Right now, these programs mostly play out within museum structures that are still committed to more traditional art-making. You’re not going to agree about how to support collaborative projects or have great workflow if there isn’t a shared institutional commitment to them in the first place.

BOAnd that sort of commitment takes foundational change. Museums are inward-facing institutions. They create programs and bring people into the museum and tell them what’s good and interesting. The current conversations about museums without walls invert this gaze. The goals of a good collaborative art project are no longer inside the museum, but outside, in people’s daily environments. Before you talk about collaboration, let alone their social impacts, you should be talking about this very philosophical question of what museums do.

MTWhat roles do you see opened up for artists and curators through collaborative work or through this model of museums without walls?

BOOver my creative career, the example I’ve learned the most from is Robert Irwin’s Symposium on Habitability of Environments. Irwin was collaborating with NASA researcher Edward Wortz and was unhappy with the way NASA defined habitability. The approach was very mechanistic: If we give you this much water, oxygen, food, and room to move, you’ll survive in space. Irvin wanted to talk about human needs in more complicated ways. So he created this symposium with experiential elements—different lighting schemes, sound interference, more or less comfortable seats, openness to the street outside—that prodded the scientists to consider the question of habitability from new angles.

You can draw a direct line from the symposium to what we now call socially engaged art. When Tania Bruguera partners with the Queens Museum on the Immigrant Movement International, a community space to address issues facing immigrants, or Theaster Gates founds the Dorchester Art and Housing Collaborative or Rick Lowe creates Project Row Houses to respond to housing concerns in Chicago and Houston, respectively, it’s exactly the same line of thought. “Here is an issue that needs attention, and I, as an artist, have agency and the skills to engage with it.”

MTAnd I want to underline something implicit in what you’re saying—that artists don’t just have skills, but knowledge, to share. I read about Irwin as a young artist and found it incredibly empowering to learn that he sat in his house for a year painting tiny dots and paying attention to the way he perceived them, and by the time he collaborated with NASA, had some things to say about perception that made a scientist pay attention. Artists aren’t often acknowledged as subject-matter experts.

BOAbsolutely. Irwin has been so important in my development as an artist and a curator. And now I’m in philanthropy, and his work is still meaningful. His career can be described as a series of research questions interrogating the image, the mark, the frame, the environment. Each question demanded a different kind of work. But that approach doesn’t help artists get funded. To get funded, an artist has to spend their career doing pretty much the same thing.

MTWe haven’t talked much about the money side of things. But you’re moving into philanthropy. What will you be doing in your new job?

BOWhen I switched from art-making to curating, I was consciously trying to move up the art-world food chain. As an artist, I wanted to work in a research-oriented way, to ask a question and then slowly figure it out. But when you send most curators a proposal that says, “I’ll figure it out,” they will not talk to you. I wanted to be on the receiving end of these kinds of proposals and create some change.

After five years, I’ve realized that a curator only has so much agency. I can define the agenda for the Studio for Creative Collaboration, but there are broader constraints, and a lot of the time, those constraints have to do with money. It’s not enough to have artists and museum staff thinking the same way if we cannot convince philanthropists and donors to give us money to do the work. That was a stumbling block for a lot of projects. It was extremely frustrating. So I decided to move into philanthropy and figure things out from there. I am taking on the role of the Director of Programs, Arts and Culture at the Cleveland Foundation.

MTSo, we’ve talked about cultivating collaborative projects from a number of angles and needs. You need artists who want to work that way. You need institutions that are philosophically and practically committed to the projects. And then you also need people with money who recognize the value of these projects and fund the work. I’ve heard you describe it as an ecosystem.

BOIt’s an ecosystem. Yes. When I switched from art to curating, I was interested in the idea of a meta-artist—the idea that an artist can attach their work to any field of knowledge, and it’s still art. Now I’m thinking about my new position in philanthropy as meta-curating. Because what philanthropists are doing is using their money to curate art ecosystems. Philanthropists make judgments about what art should be supported and what not, and through these decisions shape how artists work, how museums exhibit, and how art is perceived by the general public. They exert an incredible amount of power and have to learn to share that power more effectively. I’m interested in how foundations can curate an arts ecosystem that is fundamentally collaborative—in taking what I have learned in the last five years at the Weisman and scaling it up to a city.