In the Eye of the Beholder: Subjectivity and Perception in the World of Art

A student perspective on how discrimination shapes what we see in the art world, and how art education might reframe standards of success

In the world of sports, there are clear winners and losers. In a race, the person to finish first is the obvious winner. In volleyball, the first team to score 25 points wins. Numbers are everything. Seconds, minutes, points, hurdle height, pool length—each becomes a factor in determining a winner and loser, success versus failure. In the world of visual art, it is difficult to establish winners and losers, but artists are similarly defined by numbers. Just by viewing two art pieces, an individual cannot say that one is objectively worthier than the other. In the absence of clear criteria for evaluating quality, such as what would be used in sporting competitions, we tend to substitute money, pointing to what is more commercially successful as the “winner.” Capitalism has crushed artists into winners and losers based on dollars and cents.1 Thus, the majority of commercially successful visual artists are white men. The exclusion of women and other marginalized identities from both the art industry and the commercial world as a whole has, in turn, resulted in the skewed perception of quality art.

Our perception of quality has been curated by institutions that have perpetuated a vision of art that is overwhelmingly white and male.2 A 2019 study from the online journal Plos One found that in a sample of around 45,000 works of art found in U.S. museums, 85% of their artists are white and 87% are male.3 Moreover, these disparities begin with who decides what audiences see. In 2013, the National Association of Art Directors reported that over 50% of their directorships were held by men, and that the likelihood of there being a male director is even greater at museums with higher operating budgets.4 White Americans are also overrepresented as museum visitors, with only around 9% being BIPOC as of 2010.5 However, being white and male need not be a prerequisite to create, enjoy, or otherwise work with art.

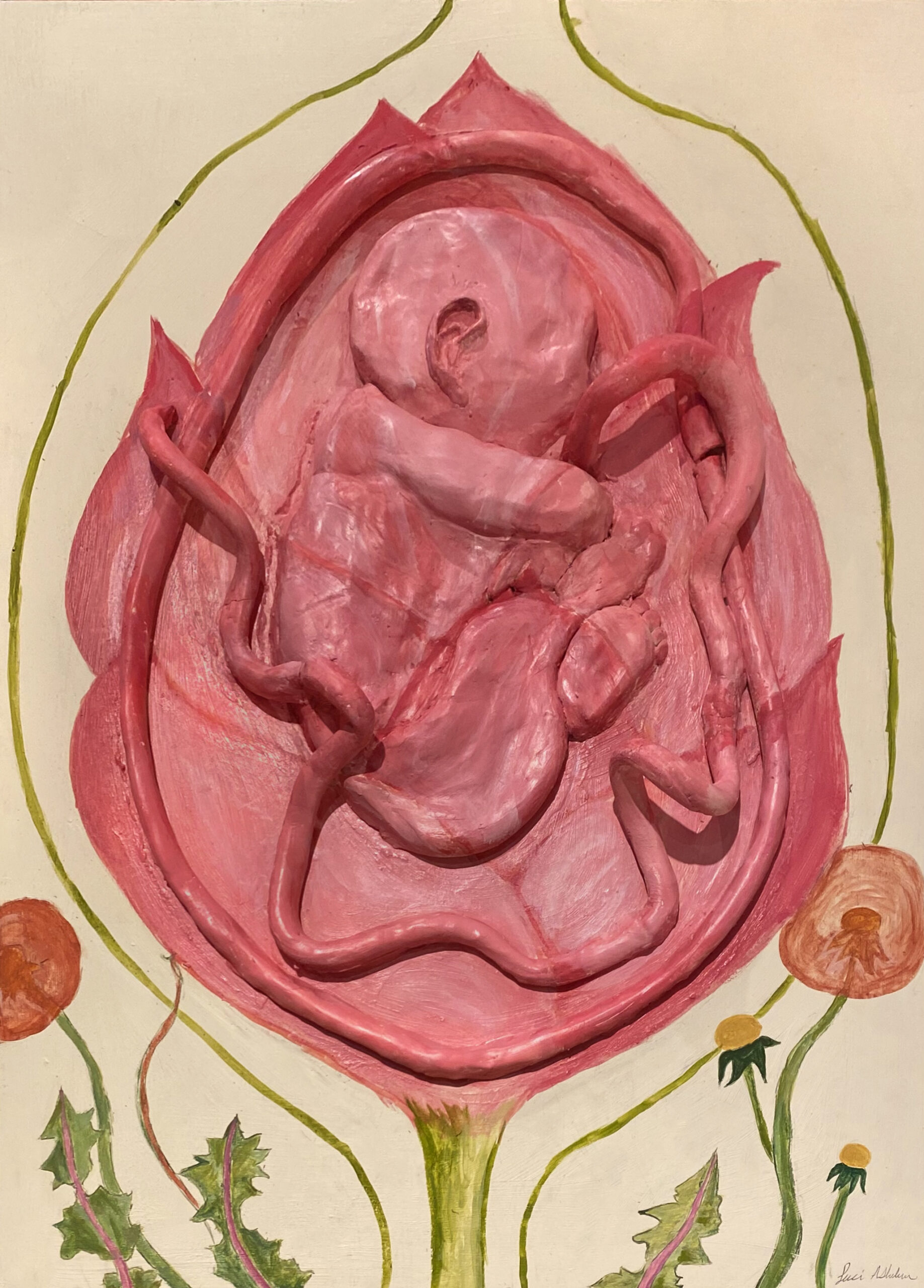

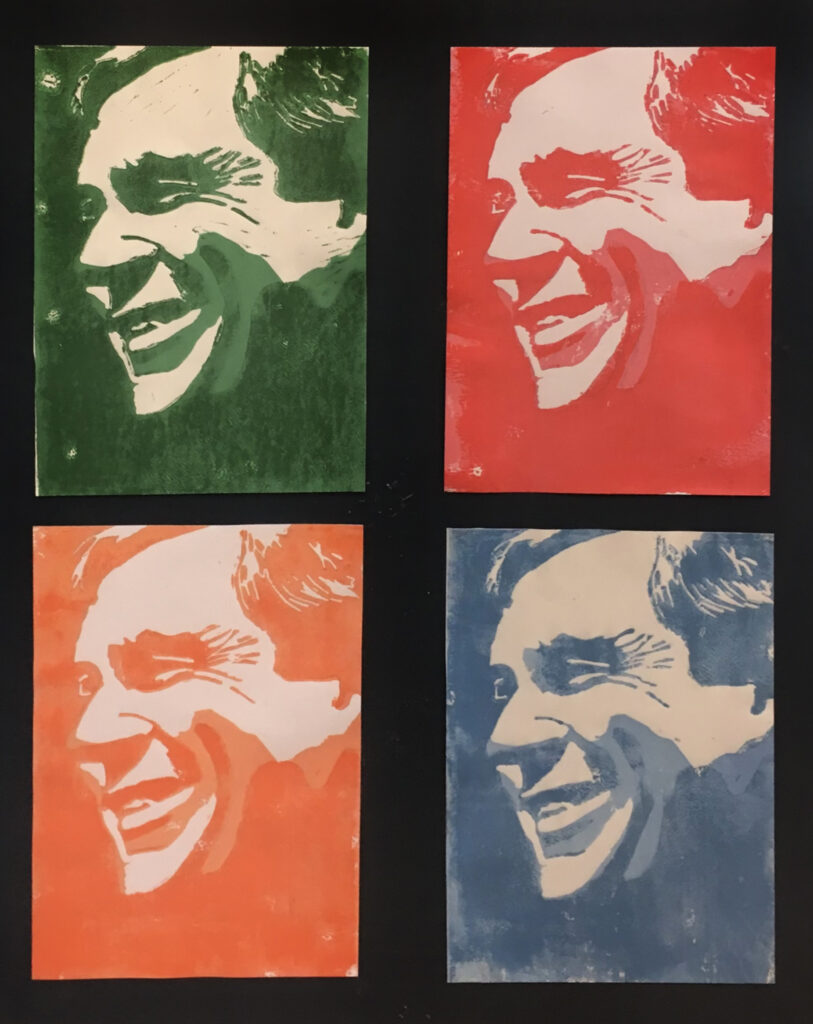

In recent years, we have seen an increase in diversity amongst museum staff, visitors, and featured artists, but it is not enough to simply hire, attract, or feature women and people of color.6 While widening access is a step in the right direction, it also builds off of an already flawed and commercialized system. We must also thoroughly examine the way we critique art. While it has been argued that factors such as technical accuracy, principles of design, and meaning define an artwork’s quality outside of class and whiteness, it must be recognized that these very criteria are born from an inherently racist and capitalist authority. The scientific methodologies that determine an artwork’s value based on color, form, and materials are produced via a commercial mindset.

Art education has been warped by this commercialization, and we therefore must teach as though we live in a classless society, teaching to value pieces that do not meet traditional (commercial) ideals of quality. In art education, money is merely one factor that need be discussed in order for us to reflect on what makes art truly worthy to us. We must encourage students to think critically about why we value certain pieces over others and expose them to a variety of artistic styles and experiences. This allows students to develop individual metrics of success untrammeled by capitalist ideals and discard the idea of objective winners and losers. To shape the next generation of museum directors, curators, artists, and audiences we must engage in constant dialogue. Truth compromises the objective as well as the subjective, both of which remain unknown without conversation.