Time Is a Boomerang: Residual Histories Wrapped in Post-Industrial Mystique

On Chris Larson's installation at the Wakpa Triennial created from the material of a vacated garment factory: absent workers, loops & rotations, and the contradictions of capitalism

“Time collapses in on itself; it is not linear; it is a boomerang.”

Christina Sharpe

The camera’s eye glides across an array of black metal timecard holders, briefly lingers on a man in glasses and suspenders who is busy drilling a clock into the wall, and moves onward, seamlessly, past a calendar (it is January and Martin Luther King’s face is printed on the box for Monday, the 17th) and down a narrow set of wooden stairs. Then, things take a turn. What just looked like a row of studs in a wooden wall shifts and turns out to be ceiling rafters complete with long skinny tubes of industrial lighting. In the glare, a lone woman stands at a table, slowly sinking the blades of bright red scissors into paper, as if she was cutting sewing patterns—but very slowly. The roving eye of the drone camera moves past her before sidling up to another wall, where in a now no longer unexpected twist, the perspective changes and effectively upends spatial certainties. This time, the posthuman gaze of the invisible machine closes in on where there should be a corner; there isn’t one. Instead, another room appears: three walls covered in shelves that hold innumerable spools of industrial thread in colors ranging from all the hues of denim blues to greens, and fleshy pale pinks next to flaming reds, oranges, and yellows.

Visitors of Chris Larson’s latest exhibition, The Residue of Labor, would likely recognize the space as The Thread Room (2022), installed and accessible onsite. In the video, the thread room is one of 12 spaces that Larson and his crew built to produce the mesmerizing nine-minute loop, The Stillness of Labor (2022). If the tradition of the still life in art has long been concerned with portraying a particular order in the world, stabilizing and regulating the proper place of objects, The Stillness of Labor—as the oxymoronic tile suggests—conjures a world where even the laws of gravity seem suspended, as the hustle and bustle of a garment factory comes to an almost standstill. The only thing capable of sustained, productive movement is the camera as flying machine, programmed to rotate with daunting precision and speed while human gestures slow down or halt altogether.

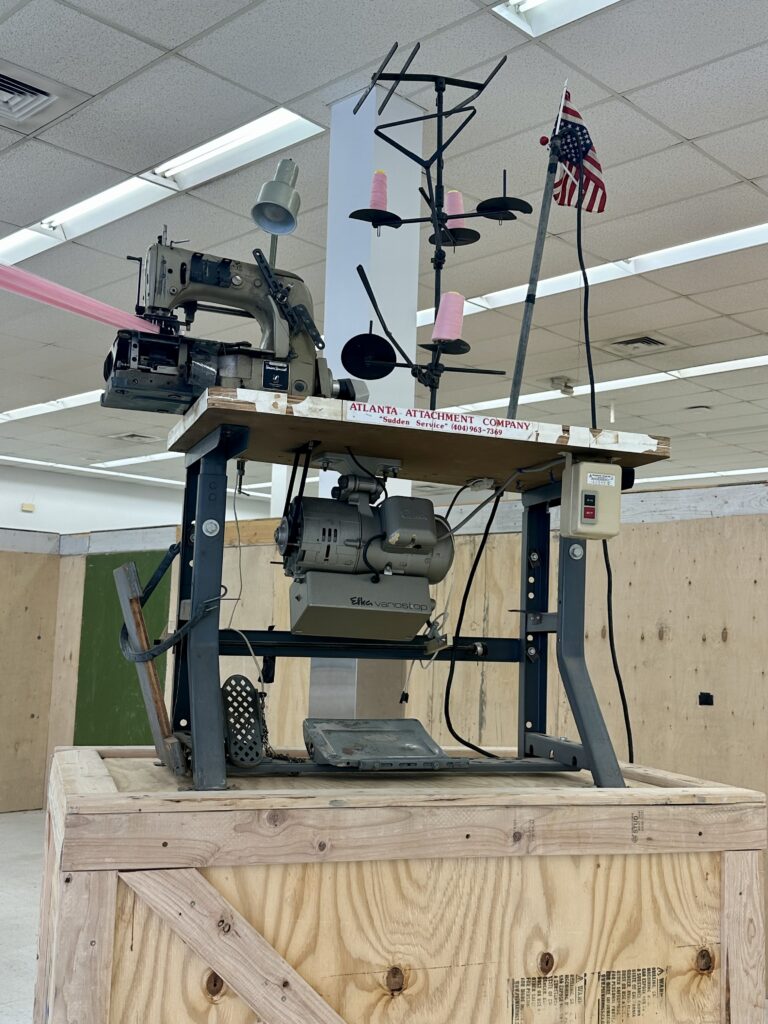

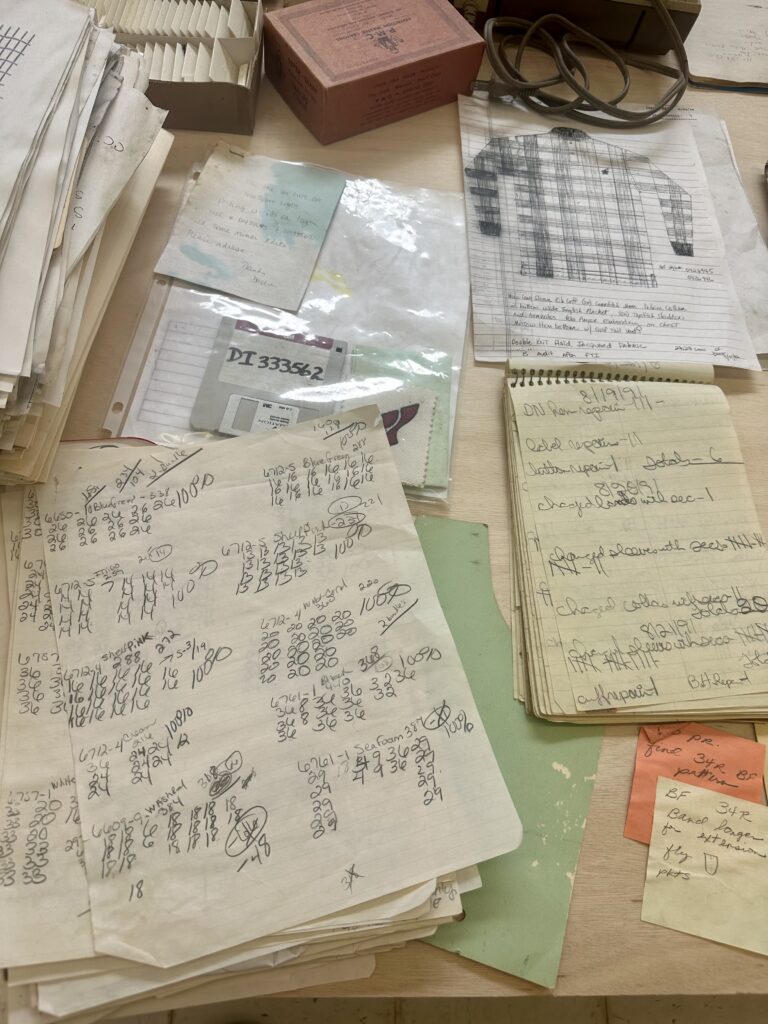

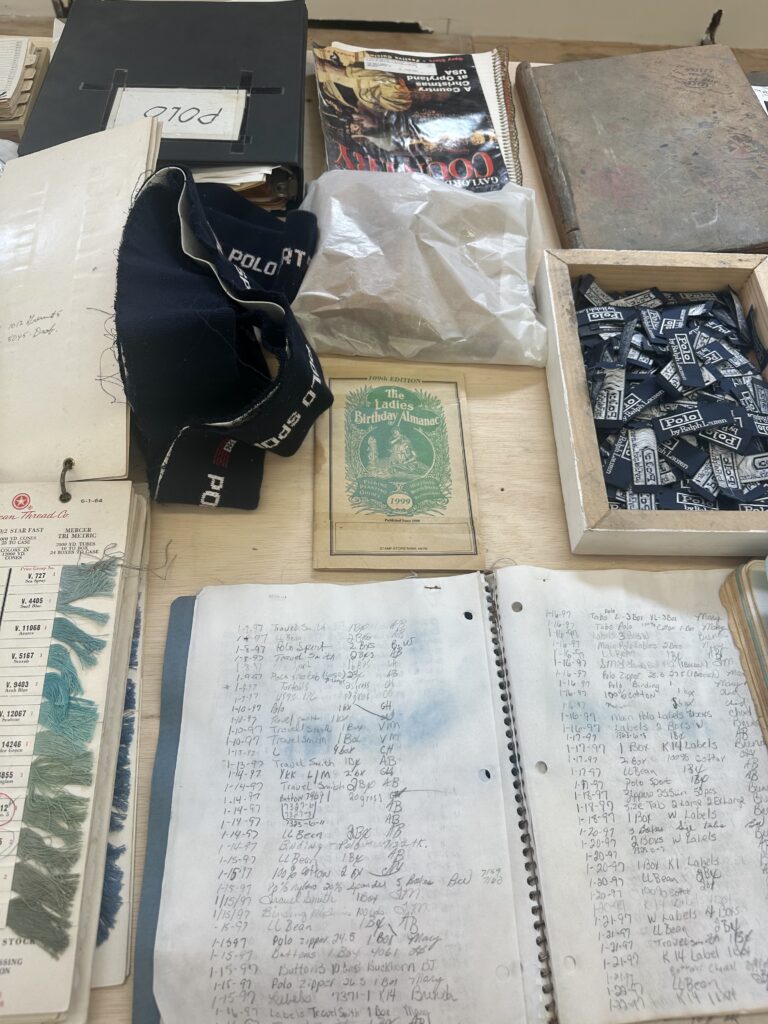

The Stillness of Labor reads as the centerpiece of Larson’s latest body of work, the result of a four-year investigation into a defunct Tennessee garment factory. A family connection brought Larson in touch with the factory, which closed in 1998 when Ralph Lauren, the long-time employer of hundreds of seamstresses, outsourced production abroad. The factory’s basement remained untouched—abandoned, but not vacated. The post-industrial debris that remained became Larson’s raw material for making art. After a series of onsite performances which involved stringing miles of colorful thread from sewing machines to rafters and back, he started sifting and sorting through the residue left by generations of workers. After a year and a half in the space and having secured grant funding for the project, he transported truckloads of raw materials to his Saint Paul studio, where the work for The Residue of Labor continued.

The resulting body of work, first on view at Chicago’s ENGAGE Projects in 2022 and now installed in a former Walgreens store on Wabasha Avenue in Saint Paul as part of the Wakpa Triennial, is as compelling to watch as it is paradoxical. The locale suits the project: both are resurrected from a state of aftermath. The exhibition’s draw lies in the way it is poised between a politics of dedication and an unsettling complicity. Designed to honor labor that routinely goes unseen or under-appreciated, the work still reiterates the logic of capitalist extraction. Raw materials, transformed through ever more specialized forms of labor, produce capital, whether material or cultural (and at what point do the two meet?) while participating, perhaps inevitably, in an art world enthralled by the capitalist machine. That The Residue of Labor does not pretend to be above the fray, immune to contradictions, or mysteriously equipped with answers—it is indeed entangled in “networks of mutuality,” as the leitmotif of the Wakpa Triennial puts it—may be its greatest strength.

Together, the works in the exhibition—two videos, sculptures, drawings, paintings, found objects, and photographs of on-site performances—conjure a sense of post-industrial mystique, replete with the contradictions of capitalism itself. Take the smooth swoop of the drone-operated camera through rooms where human activity has crawled to an almost standstill: the capacities of machines to perform tasks that once were solidly in human hands far outpaces our bodies’ endurance and skills. Yet automation, though long feasible on each level of production, has been on hold for years—for fear of leading to mass unemployment and civic unrest, as David Harvey argues. Also, who would have the means to buy all the machine-made goods if consumers no longer can afford to shop? These questions linger, even though clothes, as Larson points out in his artist talk, are still made by hand: each seam and zipper a trace of someone’s fingers smoothing and stretching fabric, lining up needle and thread, pushing a pedal to operate a sewing machine.

The seamstresses formerly employed in the factory could never afford to buy the polo shirts they made. They were paid $2.70 for each shirt but received rejects with price tags of $80 dollars. Though the loss of their jobs was not tied to automation, their presence is nonetheless precarious in The Residue of Labor. In The Stillness of Labor, the people on screen are placeholders acting their parts; the Smithville seamstresses have once again been replaced. The second video, Sewing Machine Portraits (2019), amplifies their absence as it offers intimate close-ups of machines in what reads as a metonymic displacement. The camera lingers, even caresses, the metal arms, bodies, and tabletops marked by countless hours of work. Whether the choice to leave out actual workers was intended as a gesture to afford privacy, pay tribute in absentia, a mere matter of logistics, or a deliberate centering of the defunct tools remains uncertain.

Still, absenting people amid post-industrial exhaustion and devastation is a complicated choice: The infamous “ruin porn” that catapulted abandoned spaces in Detroit to global stardom erased the people still calling Detroit home, still making a living in the wake of Motor City’s fall. Photographers flocked to the city, hunting for a haunted, post-industrial mystique. What, then, sets Larson’s work apart?

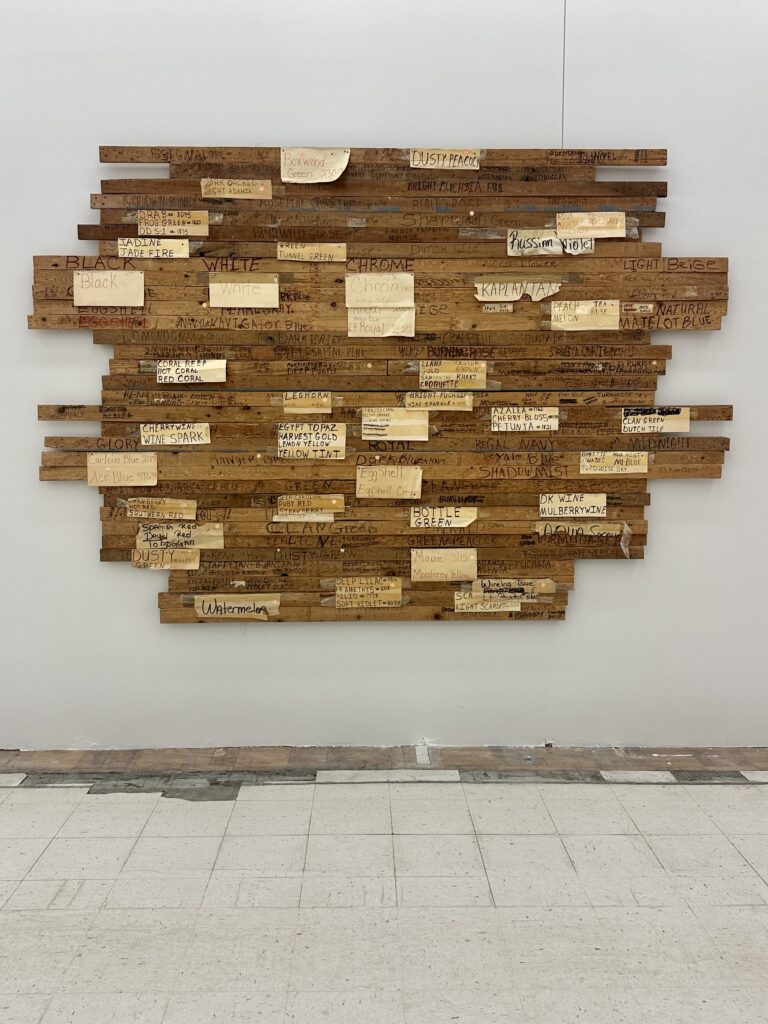

First, time. As in, the time the artist spent living in Smithville, Tennessee, sharing his lunches with the seamstresses across the street, the time spent in the basement in conversation with workers whose grandmothers used to sew there. Today, seamstresses still manufacture garments for the U.S. Army, which is one employer that cannot afford to chase cheaper labor abroad. The tabletops of sewing machines, now transformed into art, tell countless stories of gestures, repeated innumerable times, of physical routines that shaped bodies just as they shaped fabric into patterns into clothes. In a statement whose precise prose verges on poetry, Larson inventories the number of spools, counts the different colors and many miles of thread, the square footage of the basement, the height of ceilings. The numbers keep coming: average median income, crime rate, meth usage compared to the national average. Materiality meets sociology in this time-consuming accounting. Even as the work asks what happens to a community, to its people, in the wake of capital’s departure, it also begs the question, who takes the time to look, to honor work no longer prized? Who has the time?

Larson took four years. To live in Tennessee, to spend time with the community—and to make work. No quick and easy hunt for a haunting picture, but dogged determination to find ways to make that place matter, bring it to national attention, not as an abstract meditation on capitalism’s ill-gotten gains but as material history, an archive of lives and livelihoods transformed by the brutal quest for profit. Four years is not a short time to devote to one project—and yet, elevating the time it took to make the work risks fetishizing time and creative effort, mystifying the touch of the artist’s hand and obscuring the conditions of a highly specialized and very prized form of labor that deals in and ideally accrues cultural capital: namely, art. (The name of Second Shift, a residency space run by Chris Larson and Kris Zulkoski, also emphasizes labor—another shift beyond the day job, a signal to the above-and-beyond dedication of the artist as creative laborer).

When Larson moved his studio to small-town Tennessee, a resolutely red state, Donald Trump held the office of POTUS. Much political rhetoric was spilled to appeal to the forgotten working class—always imagined as white and as his staunchest supporters. Then, there were the 53% of white women who supported this presidency. The Residue of Labor does not dwell on these numbers or on this context, but it is indisputably there. So what does it mean? What to make of the anecdote Larson shares in a conversation with Sheila Regan—that one of the seamstress who was formerly employed at the factory feels “celebrated and identified”? Yes, it feels good to be seen, valued, affirmed. Christina Sharpe, in a note that addresses the work of photojournalist Julie Platner, writes, “In reality, these white people are always extended grace—and the grammar of the profoundly human. They are the human.” There is more than one thread of residual history that reverberates in Larson’s work.

The emphasis on and simultaneous absence of the laboring body and its history in a Southern state is both suspect and intriguing; the politics of (in)visibility are inevitably complex. What to some connotes treasured privacy, ambiguity, and opacity, to others smacks of systemic erasure, stigma, and worse. In Larson’s work, the absenting of the laboring body and its symbolic replacement is deliberate. The tone and feel of the exhibition is markedly different from, say, Mika Rottenberg’s over-the-top surrealist marvels of capitalism’s absurdities (e.g. NoNoseKnows (50 Kilos Variant) (2015) or Renzo Martens’ smart interventions into the process of value creation that starts at the plantation and ends at the white cube. The Residue of Labor is materially intense and seems more fascinated by machinery than human relationships. But what The Residue of Labor shares with these contemporary explorations of the politics of labor is the fundamental question of how we honor (and compensate) work as work, while holding in abeyance work as the sole raison d’être, as if only the capable body, the (re)productive body, was a body worthwhile.

That deeply flawed idea emerged with early capitalism, as Silvia Federici has shown, when the body as machine, performing measured tasks in standardized increments of time became prevalent. And measures of time abound in The Residue of Labor: timecards are transformed into paintings, timecard holders into sculpture. In The Stillness of Labor, clocks, calendars, and more timecards are ubiquitous as the ultimate and indisputable measure of output, effort, and achievement. And not only time is normatized but bodies, too. Sharpie-ed on the side of cardboard boxes, standard sizes—size 36, size 38—act as reminders that bodies are expected to fit into standard measures. But what if time (like bodies) acted and moved organically? What if we pictured time as a matter of ebb and flow, where rapids give way to eddies and pools? Or as a matter of perception, duration, and contingent on shared frames of reference, as some philosophers propose?

The Stillness of Labor disorients spatial and temporal frames of reference. Something twists, space tilts, and time becomes heterogeneic: incongruous, dynamic, and at odds with the linear progression of what Mark Rifkin calls “settler time,” that weapon of modernity and rationality, and a brutal instrument of subjection—of women, Indigenous peoples, queers, and those whose bodies were prized only for their capacity to (re)produce in chattel slavery.

Going against the grain of such linearity, Larson’s work has long relied on the theme of rotation—Heavy Rotation (2011) and Reservoir Drawing (2015) are a case in point—and cycles. Looping videos, such as Land Speed Record (2017), measure time differently, for instance, in one extraordinary polyrhythmic drum solo by Hüsker Dü, performed by Yousif Del Valle. In The Residue of Labor, rotational paintings recur along with sculptures that look like they might spin around a central axis and are assembled from timecard holders and bathroom doors. The re-cycling of creative gestures does not stop there. But though familiar, these gestures assume unprecedented significance here, steeped in living, emergent history that is far from over. And of course, these moments of creative recycling also hold the residue of the artist’s labor.

There are more residual, repurposed gestures. In Deep North (2008), the artist covered a structure with ice. In the Stillness of Labor, the deep freeze returns, though now it is steeped in additional meaning: the factory itself—a “time capsule,” as Larson describes it in his conversation with Sheila Regan—freezes a moment in time, in the history of a community. The accompanying soundtrack, too, is compelling: crackling ice follows the incessant hum of ventilation. In contrast, Sewing Machine Portraits relishes the quiet. This very pairing of perspectives and soundscapes is reminiscent of Land Speed Record at the Walker Art Center in 2017, where two similarly different videos looped facing each other. Finally, the Factory Performance Series (2018-2019) holds one more moment of recognition: the photographs of the performances in the Smithville factory’s basement bring to mind Larson’s Threshold Drawings (2017), where countless graphite lines converge on a single turning point before pivoting and fanning out. Their movement seems to flip space. In the Factory Performance Series, photographs document how this formerly abstract, conceptual gesture is reborn in color, in 3-D, in a space thick with history.

Chris Larson, The Residue of Labor, 2023. Courtesy Public Art St. Paul.

Chris Larson, The Residue of Labor, 2023. Courtesy Public Art St. Paul.

Chris Larson, The Residue of Labor, 2023. Courtesy Public Art St. Paul.

Larson owns that he addresses a history that is not his own in The Residue of Labor. And in one sense, that is true: personally, the only ties the artist has to the Smithville garment factory is a family connection and the time he spent with the seamstresses formerly employed by Ralph Lauren. It is their work he sets out to celebrate through his. The different kinds of labor involved, though both iterative, involve different degrees of cultural capital for the work and workers involved. And honoring, though well intended, may risk obscuring the manifold threads that weave a social fabric across generations—lines that pivot on inherited wealth and lack thereof. And who can trace these lines? Who validates whose experience? And from which social, historical, and cultural position? In Ordinary Notes, Christina Sharpe writes, “Visuality is not simply looking. It is a regime of seeing and being, and any so-called neutral position is a position of power that refuses to recognize itself as such.” Let’s take another look, then.

What we could see: Cotton still is Tennessee’s third most lucrative crop. Before the former shirt factory arrived in Smithville, raw materials (like cotton) were routinely shipped to Northern factories. Then, in the 1950s, the cost of unionized labor drove production to the South, where sharecropping, which had been on the rise since slavery’s end, was declining as farming became increasingly mechanized. Replaced by machines, workers flocked to factories. Labor was cheap. Until it was cheaper elsewhere. Time is a boomerang.

What we could notice: the seamstresses are not the only people not pictured in the work. While their absence could be explained by logistics or respect for their privacy (a concern Bathroom Doors (2022) explores), Larson, who acted as the protagonist in a number of his past moving image works, does not appear. This absence, too, invites more than one read: to not center the artist in a story that ostensibly is not his conveys a form of respect; but given that “who writes, how one writes—as in from what subject position—and what one writes matters,” as Sharpe succinctly puts it, perhaps it is important to know who is “writing” what—exactly and especially because this history is posited as not his own.

So, the seamstresses are missing. The artist’s presence is only implied. Who, then, takes center stage? Who is the subject of the residue of labor? My answer: the machine. Like nested matryoshka dolls, machines make the work: the sewing machines; the drone-enabled visions of The Stillness of Labor; the three generations of machines that Larson constructed to produce the thread paintings in the show. Picture two thin metal arms, purposeful and sharp, moving around canvas-covered shapes and wrapping each one in colorful thread, like some injured machinic spider cocooning her prey. Each iteration of the machine offered more precision and control. More mastery. The machine is not on view; only the resulting thread paintings are. Named for the hues of yarn used to make them—Carlous Blue, American Beauty, Greenette—the paintings riff on the many artists who have painted stripes, vertical and horizontal, monochrome and not. But rather than paint, these works harness miles and miles of thread. Most importantly: they are made by machine. And nested in centuries-old capitalist machinery.

The very locus of creativity shifts from engaging a canvas to the construction of malleable machines—as if to suggest that creative labor, too, could be outsourced and better performed by machines. Far from expressive, the thread paintings bring the work full circle: creativity is industrialized here, outsourced to manufacture by a smart machine. No more identity politics to muddle the picture, just the clean churn of inventions that render obsolete a maker. In the age of AI and markets in predictive behavior produced by algorithms, could there be timelier questions? Though ostensibly concerned with the past, the residue, what the work does is pivot. Time is a boomerang.

Chris Larson’s The Residue of Labor is on view through September 16, 2023 at 425 Wabasha St. N., St Paul, MN 55102, with open hours Thursdays 12-6 pm and Saturdays 12-4 pm. >> more information

Note: Christina Schmid teaches at the University of Minnesota’s Art Department, where Chris Larson is an Associate Professor.