Lunch Break

Two artist-educators consider flexible teaching methods, fostering autonomous growth, and the purpose of critique

Introduction

Throughout the last academic year, Emmett and I have had ongoing conversations about our teaching methodologies from teaching art at University of Minnesota and Minneapolis College of Art and Design. For me, it feels affirming to connect with educators like Emmett to broaden my perspective and validate the challenges that I experience. I consider Emmett a mentor and am grateful for his collaborative mindset and enthusiastic support. After the school year ended, he invited me to his home on a hazy summer day for lunch and we reflected on the year.

Isa Gagarin

EMMETT RAMSTADYou introduced me to small group critiques, which I tried out in my own classes. Can you tell me about your critique methods?

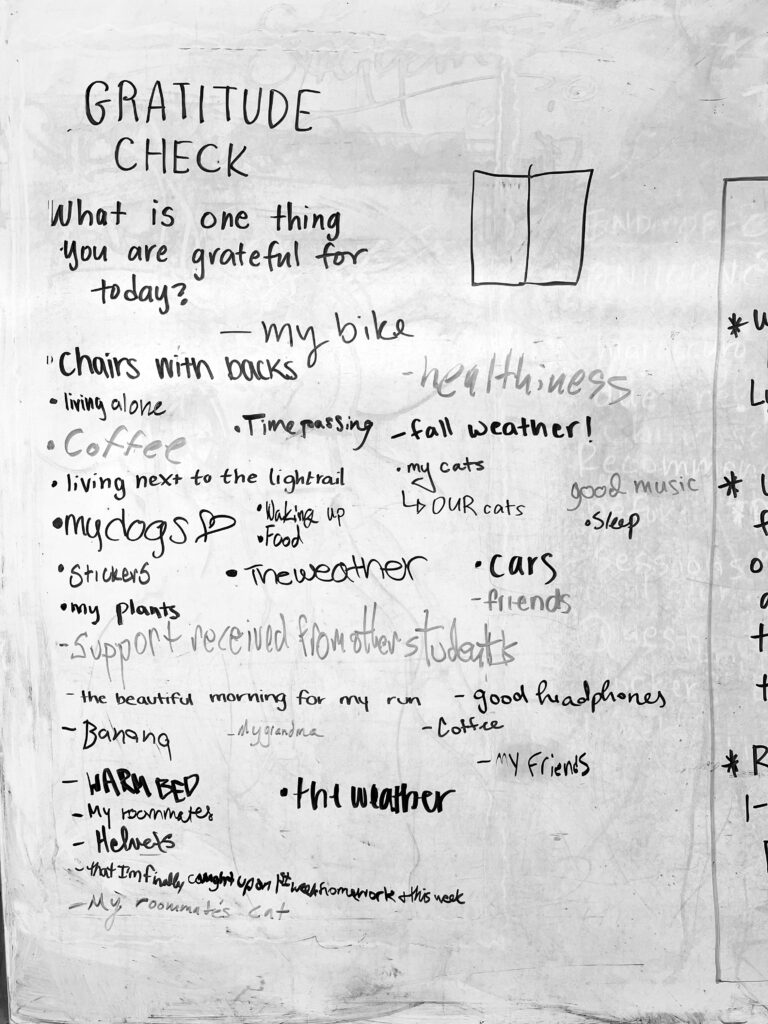

ISA GAGARINSomething that I find problematic about conventional critique structures is the element of performativity. There is an unspoken pressure for students to perform their participation for the instructor and for the success or failure of student work. I wanted to question that power dynamic, so I experimented with dividing the students into small groups for peer-to-peer feedback. Five people turned out to be a sweet spot: not too small, not too big. I would provide conversation prompts, such as, “What stands out to you about this artwork? What emotions or ideas do you experience? What visual elements of art convey those emotions or ideas?” Then, I would give students time and space amongst themselves to talk in a natural way. The next week, I would follow up with each student to check in and reflect on their critiques. I found that the students felt satisfied with the responses they received, and the follow-up conversation gave them an opportunity to ask for additional feedback. Near the end of the semester, I learned that the students wanted to share their final projects with the entire class, so that their work could be fully seen and honored. By then, they were more familiar with each other and confident in sharing feedback.

ERThis method made me reflect on how much my own ego has informed my role as a facilitator during critique. When I first experimented with small group critiques, I floated among the groups and felt a sense of loss because I realized how much I wanted to lead the conversation. I felt left out! But our job as teachers is to facilitate discussion, not dominate them. I think it’s important to know when to step in and guide, and when to step back and observe.

IGThere is a section of Ungrading1 that refers to Daniel Pink’s book Drive, in which he says that there are three primary motivations driving people to learn: autonomy (the desire to be self-directed), mastery (the urge to get better at something), and purpose (the idea that what is being done has meaning). I think that small group critiques give students a sense of autonomy. It becomes more about a group of peers sharing authentic feedback, rather than saying what they think the teacher expects them to say.

ERI noticed that nowhere in that book does it say learning happens because the teacher told you so. [Laughter.]

IGYes. Ungrading also helped me recognize that my courses are not the center of the universe. For example, my course Mixed Media on Paper is one of five (sometimes more) courses that a student takes in a semester, not to mention the dozens of courses they take throughout college. Two years from now, some of my students might not remember my name. But hopefully they will have gained some skills and confidence in their creative process.

ERDifferent students need different approaches. It’s hard to look beyond my personal learning style: I love learning, but some of the courses I teach are required and students are just taking it to graduate. I ask students what success looks like, and for some of them it’s just showing up, and for others it means making three paintings. Some have really simple expectations, while others have inflated expectations for what they can do in a semester. My job is to say, “Yes, that’s all amazing, and for the next three months let’s make a container that works for you and your goals.”

IGI can relate to that because I have a strong desire to tailor my instruction to individual students, which is time-consuming and sometimes impossible to do with larger groups (my courses have up to 20 students.) The struggles that I face are not because I am bad at individualized instruction, but because I have too many students for my teaching style. Fortunately, I am able to supplement teaching by participating in mentorship programs—I have mentored artists at Public Functionary and at the MCAD MFA program—and those have been really rewarding experiences for me. Communicating one-on-one is my ideal way to engage with an emerging artist and their work.

ERThere is value for you as an instructor in one-on-one conversations, while there are different kinds of value for students in small group or large group conversations. Just today, I attended a two-hour workshop on Zoom, and I appreciated being able to choose how much to engage. Sometimes I participated, sometimes I had my camera off. My interest peaked and waned depending on what was discussed. It’s the same thing for our students: they come to class with varying degrees of interest. Maybe they had time to eat before class, maybe not, maybe they slept the night before, maybe not. For me, meeting with individual students is important, but I also really enjoy putting together lecture materials and delivering a good show. Students can take from it what they want. There are so many different ways to learn. Some people are kinetic learners, others are visual learners. As a teacher, I’m asking, “How I can reach as many of these different styles of learning as possible?”

IGDo you feel that deadlines for individual assignments serve your classes?

ERI do. Deadlines serve me as a person and as an artist too. But I also think it’s important for all kinds of reasons, including access, to have soft and firm deadlines and not penalize. I don’t think penalizing students is ever really useful.

IGI agree. I think that there should be enough structure that students don’t feel lost in what they’re learning and flexible enough to accommodate different ways of working. In my studio courses, one student might make a drawing in a day and another student might need four weeks to chip away at a labor-intensive drawing. As a teacher, how do you discern when structure is needed and where you give room for flexibility? Maybe there’s no right answer, it’s just that you have to hold both as part of your approach.

ERThis makes me think of a student in my Professional Practice class that told me in his final self-evaluation that he felt disappointed because he thought he was going to learn “insider tips” on “how to become an artist” in my class and his disillusionment in the class grew over the semester when he realized that I wasn’t going to teach him a specific “success” formula. My response to reading his evaluation was: “Well, I didn’t do a good enough job teaching that goals and career choices are driven by YOU.” When I have lessons on how to identify learning styles, how to set goals, and how to evaluate yourself—those are career skills! I didn’t have and I don’t have the answer for how he’s going to do his career right because if I did…I mean, talk about ego. [Laughter.] I do teach writing for the arts, documentation and portfolio building, and loads of other super valuable skills. But no formulas. I believe that my job is to create that container so that students can learn specific things—yet it’s flexible enough to grow with them. I love metaphors, and I was thinking that the classroom is like a uterus. It is a flexible container designed to support a growing fetus which eventually reaches the limits of the container and emerges. The classroom is a space for growth and change, and it is a collaborative process.

IGI can understand that metaphor. My personal experience with labor and delivery reframed my relationship to pain, because it has an important function in the birthing process. Some of the best learning moments in my classrooms have been times that felt awkward, uncomfortable, and unresolved. Sometimes a student asks a question about art that no one can answer. Those moments of discomfort can be really powerful.

ERWhen students are uncomfortable, I notice my caretaking tendency kick in. I want to make learning easier for the students, that’s my job, but it’s not my job to take away discomfort or hardship. In reality my job is to give tools so that students can solve problems themselves in a supportive environment. Which is why when you taught me your small group critique method, I was like, “They’re doing it themselves!” Because you know what, they’re going to do that when they graduate, they’re going to give each other feedback and I am not going to be there to tell them the right way to do it—nor did I ever have the right way to begin with. But I can teach the skill of coming together!

IGIn my recent introductory drawing course, during midterm reviews, I asked students, “What makes a drawing successful?” The vast majority of the students responded that a drawing is successful when the artist is satisfied with their work. I was surprised by that. In the following critique, I gathered the students together and asked, “If a drawing is successful when the artist is satisfied with their own work, then why do we share our work with the world? What is the purpose of feedback and critique?”

ERWhat did they say?

IGI think it was the first time a lot of students were confronted with that question, which makes sense in the context of an introductory studio art course. Some students said that they share their work to get feedback on improving their technical skills. Others said that the reason to share art is to inspire others (because the reason they look at art is to find inspiration). As a result of the conversation, during the following critique students shared feedback in an intentional way.

ER“Why do we share our work with the world?” is the companion question to “What’s the purpose of art?” or “Why make art?” My students have given a number of answers, but it usually comes back to: “It’s meaningful for the maker and it’s meaningful for the audience.” In an introductory studio art course, students are in the part of their career where they’re not focused on the audience. Whereas in Professional Practices, we’re often talking about communicating with an audience…

IG…And you are guiding the students out of the university, towards sharing their work with audiences outside of the classroom setting.

ERIn a way then, critique asks, “How do we socialize? How do we consume artwork?” Because a lot of the students now are facing imposter syndrome from social media, and they’re comparing themselves to each other, but they’re not in direct dialogue with each other. So in critique they’re learning how to talk to each other face to face, which is really hard. And they’re learning how to be in community. To me, critique is really powerful because it teaches students that feedback is valuable. They are learning to communicate for the goal of giving and receiving support in an art community. And by the time students come to my senior Professional Practices course, they are learning how to use those skills to create artist communities outside the institution, which is like you and me! When I teach seniors, I’m like, “You’re here now, and I’m teaching you what I know, and then tomorrow when you graduate, you’re my peer.” That’s what’s cool about art! You might be an emerging artist, I might be a mid-career artist, but we’re going to be applying to the same shows in Minneapolis. And more and more often former students get into shows that I don’t, and I find this exciting!

Final Reflection

Besides teaching itself, one of the most rewarding parts of being a teacher is dialogue with fellow teachers. It has been an honor to share these pedagogical spaces with Isa. She makes me want to be a better teacher and continue to ask myself, “Why am I doing what I am doing? And how could I be doing it differently?” I see our conversation as a reflection of the success of art for building supportive and generative community. Thank you to our students, who teach us so much. Thank you to Brooks Turner for organizing this series. Thank you to Emily Gastineau and the Walker Art Center for coordinating this publication. Thank you to the institutions who hire us to teach their students.

Emmett Ramstad