Make Some Scribbles and Hope for the Best: Reflections on Ungrading

How changing evaluation standards can open new possibilities, not only for learning but for seeing the world

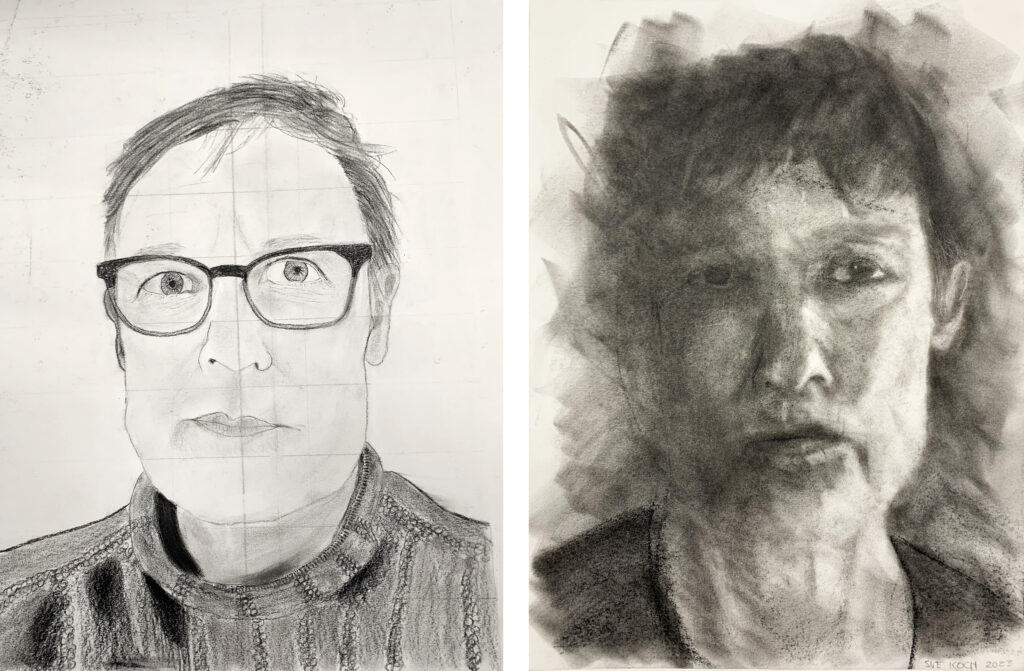

Throughout the 2022-23 academic school year, I tried something new while teaching studio art courses at the University of Minnesota. I learned about the practice of ungrading from a friend: instead of using rubrics and letter grades, she assessed student progress through direct conversations with students and written feedback. “Check out Jesse Stommel’s blog,” she suggested.1 This led me to read Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (And What to Do Instead). Learning about alternative forms of assessment gave me a huge sense of relief. Previously, my teaching strategies were shaped by an unsettling sense of imposter syndrome. Although I had worked as a teaching assistant during my MFA studies, I lacked the guidance and information that I needed to understand how learning works. I overextended myself by writing meticulous class schedules, detailed lecture notes, and exacting assignment rubrics. I was fixated on standardized concepts of success, perfectionism, and correcting student behavior. Ungrading helped me build on my natural strengths as an artist and become a more authentic educator by focusing on what I was teaching and why.

The philosophy of ungrading proposes that students are experts in their own learning.2 When I got rid of letter grades for assignments, my first goal was for students to feel engaged with their learning and progress. “What is a drawing?,” “What makes a drawing successful?,” and “Why do we share our work with others?” were among the key questions that I repeatedly asked them. They responded in the form of self-reflective writing at the beginning, middle and end of the semester. The students’ reflections informed my lesson plans and helped me identify specific feedback to share on their work. Knowing that my courses required a final letter grade at the end of the semester,3 I included basic grading criteria for participation (attendance, sharing feedback with peers) and artistic growth (creative process, advancement of technical skills) in the syllabus. During midterm reviews, I met with each student individually to discuss their progress and mutually agree on a midterm letter grade. At the end of the semester, a final self-reflection assignment (modeled after Susan D. Blum’s example)4 offered students the opportunity to propose their final grade based on a holistic understanding of their learning experience. By answering a series of detailed questions about attendance, participation, creative process, and skill-building, the students defined their academic progress in relation to their work at the beginning of the semester, as opposed to standardized metrics.

One of the research studies cited in the Ungrading book demonstrated that even within standardized subjects such as math, grading is “inconsistent, subjective, random, arbitrary.”5 I thought of charcoal still life drawings that I had graded in the past, when I gave higher marks to drawings featuring gestural lines than ones drawn with thin lines. I decided to set my evaluation standards aside (which were based on my aesthetic preferences and desire to see confident mark-making) and provide feedback focusing on the fundamental elements of art such as line, shape, form, texture and value. This enabled me to treat all drawings equally: whether they were painterly abstractions or anime-style character designs, I provided observations based on elements of drawing. I also started asking students more specific questions about their work, which helped me understand what they were trying to achieve in their drawing (such as emotions, the texture of foliage, or the illusion of volume). As a result, I focused on supporting the individual growth of students and their unique interests and goals.

I started to look more specifically for when learning actually occurred in my classroom, and I found that productive learning can happen during times of discomfort, unanswerable questions, and conflicting ideas. For example, during a critique I realized that nearly half of the drawings presented were incomplete, and the conversation was faltering. I paused the discussion and asked the students if there was something getting in the way of completing the assignment. After some awkward silence, they were generous enough to inform me that they were unmotivated by the subject matter (a still life featuring a model of a human skull, striped fabric, and geometric objects). Confronted with the fact that the still life I had lovingly composed was agonizingly boring for the students to draw, I returned to the learning objective. The goal of the assignment was to use lines, shapes and forms to create a balanced composition and the illusion of space. In a moment of improvisation, I cut the critique short and invited the students to alter their original work by adding new imagery, drawing from imagination and expressing emotions. By altering the assignment and giving students the freedom to draw subject matter of their choice, they were able to reignite their creative motivation and return to the content of the lesson.

That experience was a watershed moment for me, because I gave myself permission to trust my intuition and focus on what I was teaching and why. Doing so freed me from fixating on conformist behavior and participation, such as arriving on time and producing assignments on a fixed schedule. One day, I asked a student how she created the textures in her landscape drawing. She shrugged. “I just kind of make some scribbles and hope for the best.” That statement stuck with me, and I try to keep it in mind as I embrace the process of trial and error in my own teaching. Ungrading helped me gain insight into the ways that perfectionism had previously infiltrated my teaching practice—which is ironic, because I pride myself on teaching students how to overcome perfectionism in their drawings. But like drawing, teaching requires adaptation and flexibility. My courses never quite go exactly as I imagined. Sometimes an assignment fails to capture student interest. I start every semester with a vision of teaching, but in the following weeks I make changes and adjustments depending on the needs of the students, the social dynamics, and the overall workflow.

One example of how ungrading shifted my perspective is a conversation that I had with a student who I will call Frank. Frank was a computer science major who took my drawing course on a whim as an elective. He was 20 minutes late to nearly every class, and made a charcoal drawing of a frog “because it looked cool.” As much as I wanted him to, Frank did not seek my feedback on his work or stay after class to ask about the artists that I shared in a presentation. During Frank’s midterm review, we looked at his portfolio and I asked questions about his work. “What stands out to you about your work so far?” He shrugged. “What is something that you know now that you did not know at the beginning of the semester?” He pointed to the frog drawing, “I learned how to make the frog’s skin look shiny.” After straining to encourage him to elaborate on his answers, I arrived at the important question of the day: “What grade would you suggest for yourself today?” Frank paused for a moment, and said, “Well, I would give myself a B because I’m always tardy. But I do all the assignments.”

Simple as that. No obsessing over the details of the grading criteria in the syllabus, which I would have done if I was calculating his midterm grade the way I used to, wasting away my weekends on my laptop. What struck me the most about Frank’s answer, though, was that it helped me recognize that he was drawing. And drawing quite well, actually. In the first half of the semester, he learned how to use an entirely new medium and improved greatly in his technical skills. His frog drawing was really cool, because he mastered the use of charcoal to create an illusion of its shiny, reflective skin.

Ungrading taught me to pay closer attention to my students’ work, and to recognize that, as Susan D. Blum writes, “our principal task is educating all students, not ranking them.”6 Before ungrading, I would have penalized Frank for his tardiness. I would have agonized over my written feedback on his work, attempting to lure him into deeper critical thinking and losing sight of the context of an introductory course. I would have nitpicked over the presentation quality of his drawings. Most of all, I would have become preoccupied with winning him over, because I interpreted his ambivalence as a rejection of my teaching. Ungrading helped me develop realistic expectations about students’ behaviors and attitudes in my courses. When teaching classes of 20 or more students, including non-art majors, it’s problematic for me to assume that every student will be an enthusiastic apprentice of my field. My philosophy of education is not necessarily reflected by higher education systems and the pressure for students to enter a competitive workforce with increasingly limited access to creative careers. But for 15 weeks, I can provide a creative space for reflection, observation, and discourse. The reason I teach is to share my passion for drawing and its potential to express unique ways of seeing and experiencing the world. Ungrading gave me permission to share my passion more authentically, with the wisdom that students will receive and work with my teachings in different ways.

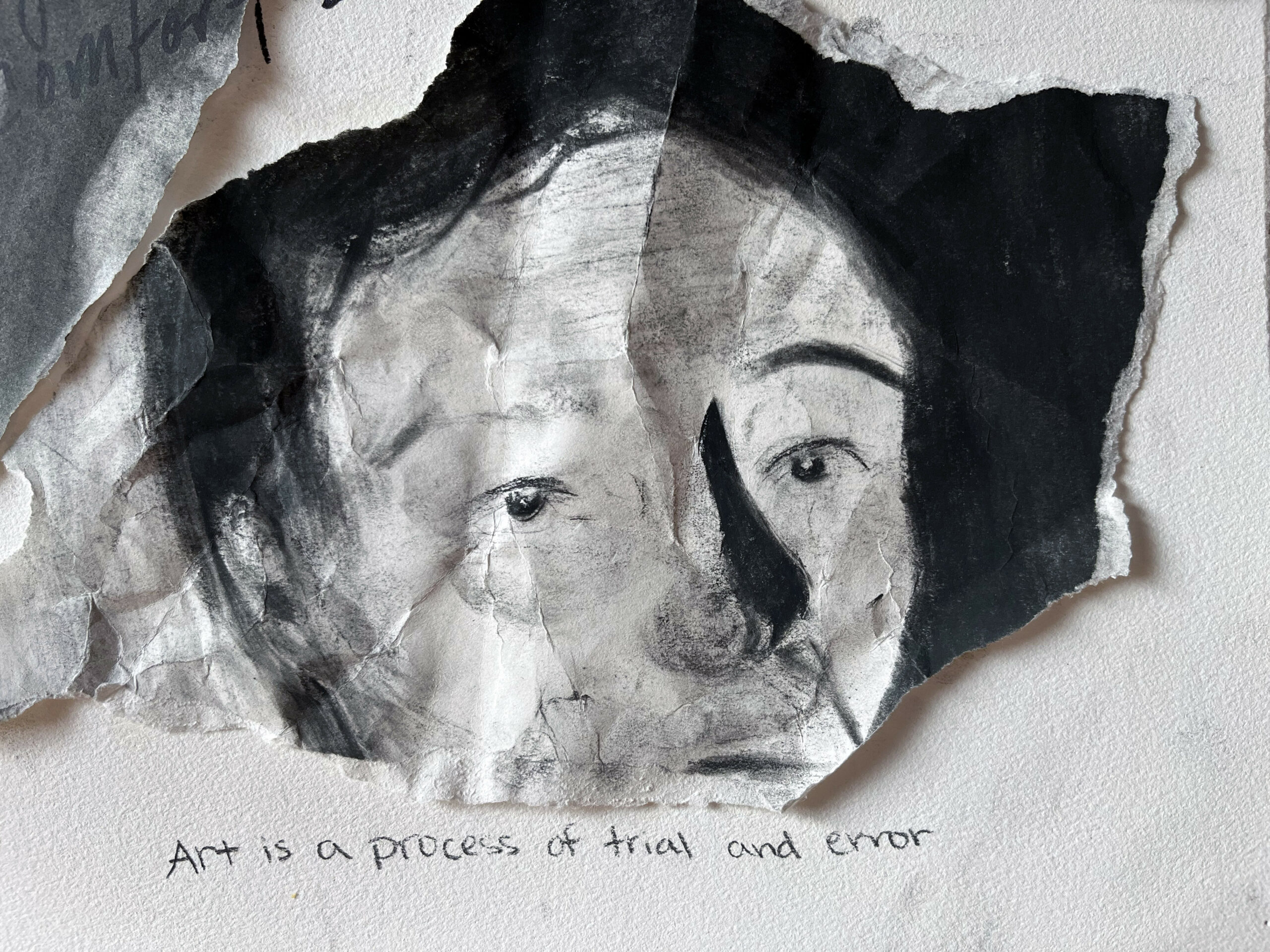

For many art students, their fear of making mistakes is the biggest hurdle in learning how to draw. Gesture drawing with vine charcoal is a method for overcoming that fear: a live figure model strikes poses for very short periods of time and the student quickly attempts to draw fluid sketches based on what they see. Over time, the student learns to trust that it takes repeated practice to capture the essence of their subject. One way that I encourage students to let go of their expectations is by promising that on the last day of the semester, they can destroy one of their drawings. After the final critique, each student ceremoniously destroys their least favorite drawing assignment, glues a scrap of it to a poster, and writes down a piece of advice for the next generation of students. By then, many of them have learned how to draw with greater confidence, knowing they can fix mistakes later on. They have also started to question and redefine what makes a drawing “perfect” in the first place. Ungrading helped me understand that the same wisdom applies to my work in education. Redefining the terms of success will help me work towards a more inclusive and accessible classroom, by honoring and trusting students as experts in their own learning.