In Our Own Image: Movement Architecture’s “Ode to Dolly”

Camille LeFevre recently took in "Ode to Dolly, the Sheep, Inter Alia" (at the New California Gallery through December 13); she found it to be a trenchant, albeit occasionally squirm-inducing, look into the issues surrounding human cloning.

IN THE OCTOBER ISSUE OF WIRED, in a section celebrating “12 Shocking Ideas That Could Change the World,” Gregg Easterbrook argues in favor of human cloning. “Nature wants us to pass on our genes; if cloning assists in that effort, nature would not be offended,” he writes. Besides, clones already exist in human reproduction: they’re called identical twins, Easterbrook continues. Every child, regardless of their origin, grows up with a singular set of experiences that make them who they are; clones would be no different. Another life-creating technology, in-vitro fertilization, was once considered the devil’s work and is now commonplace. One of the few drawbacks to cloning is the technology isn’t perfect yet; mammalian cloning-as with sheep-often produces “sickly offspring that die quickly.”

Still, in 1996 Scottish scientists produced one of the first and most famous mammalian clones, Dolly the sheep, who lived for six years. In the United States, however, cloning largely remains a cultural taboo, considered by many to be a deathly harbinger of technology-run-amuck, more likely to produce monstrous versions of the human form than cuddly, gurgling babies. Such is the stuff of choreographer Deborah Jinza Thayer‘s new work, Ode to Dolly, the Sheep, Inter Alia, being performed through December 13 at the New California Gallery in Northeast Minneapolis.

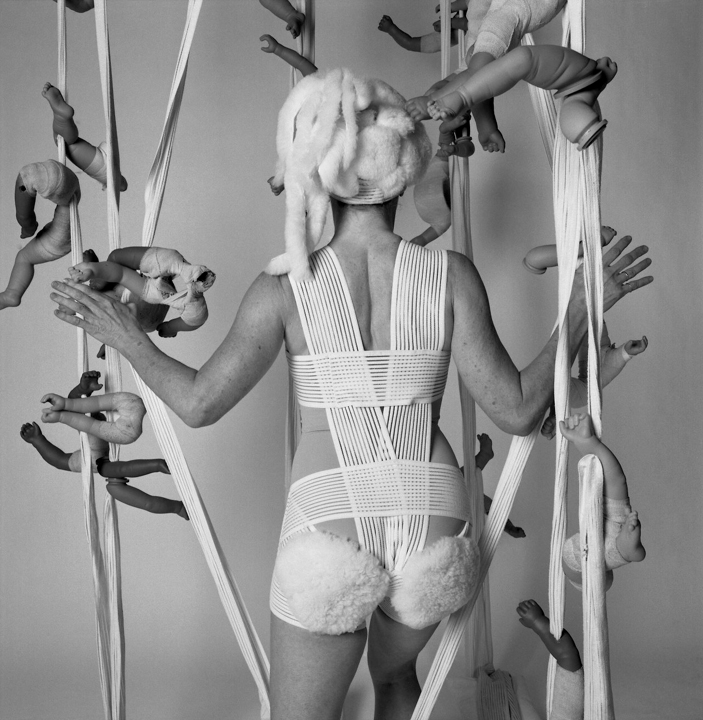

The six performers in Thayer’s all-woman cast are made to appear as clones. All wear off-white, moppy, faux-sheepskin headdresses that flop like docked lamb tails. The women’s torsos are scantily wrapped in white, wide elastic bands, which look as if they may have a medical use in real life. Sheepskin-like pads cover breasts, butts, and pubic bones (Lisa Axell and Laura Adams created the costumes). And the women all have pale faces, red lips, and dark eyes framed with long, black, ewe-like lashes.

It sounds goofy and it is — initially. The piece takes place in a very cold gallery (on opening night, audience members kept on their coats and tightly wrapped scarves around their necks) that has been divided into sections strung with forests of those same white, wide elastics on the performers’ bodies, intertwined with plastic baby-doll parts (set design by Bryan Axell/3 Ring Scenic). Throughout the work, the audience moves from one side of the gallery to the other, and may even encounter one of the clones up close and personal (more on that later).

The work opens with Creation Myth, in which three of the dancers (Penelope Freeh, Christine Maginnis, Kimberly Richardson) are on a platform, manipulating the puppets (by Deidre Murnane) underneath them with strings attached to bottle nipples. As Matthew Smith’s score tinkles and trickles like an electronic, singsong version of baby talk, the dancers jiggle their puppets, bat and tug at the baby-doll parts strung on elastics overhead, and mechanically waggle their heads; they percussively thrash in something like birthing throes, and give each other quizzical, comical stares throughout.

The next section, Birthing the Forest, has all of the performers attached to elastics — still strung with doll parts — which they stretch across the gallery as they struggle, twist, and crawl from one side to another. Despite the work’s intriguing premise and evocative setting, it’s somewhat predictable. The movement is purposeful, but not extraordinary. And several of the dancers’ blank, doll-like expressions and/or comic mugging we’ve seen before. When Maginnis, a veteran of the Twin Cities performance scene, turns on her comedic character, we’re familiar with her sly-eyed, curved-lip expressions. Similarly, the much-younger Richardson has built her career to date on doing wide-eyed, deer-in-the-headlights characters noted for their dotty blankness and comical expressions of surprise.

And this is why the duet between relative newcomers Rachel Barnes and Sarah Jacobs, in the third section of the piece, is so compelling. Titled Bizarre Mating Ritual, the duet takes place in a section of the gallery strung with a vertical grid of elastics with doll parts. Like two feral creatures flirting, they crouch, stomp, and flick their heads and limbs in a strong, intriguing, and gestural communication of quirky innocence and tacit acknowledgement of the curious environment, and perhaps even set of expectations, in which they find themselves.

There’s humor in their interactions, as they test and discover each other’s physical tolerances and boundaries. But rather than being merely bizarre, this mating ritual has an element of truthfulness that allows it to supersede species or gender specificity. Yes, Barnes seems the more assertive of the two (which she’ll definitely prove later in the show), with her clear, quick, lithe movements. She sidles up to Jacobs again and again, finally seducing her by planting baby-doll parts on Jacobs’ body, then sandwiching them into place with her own body before the two women spin off to another part of the gallery.

A turning point in the performance, this duet introduces an odd pseudo-sensuality into the piece, infused with choreographic and character intrigue. Barnes and Jacobs, unlike their “sisters”, have emerged as clones with distinct personalities that they wield with otherworldly effect. Sharon Picasso does as well, when she emerges in Is It Artificial? on a rolling platform wearing a second head, propelling her horrible configuration of limbs, complete with two sets of legs. While Maginnis and Richardson set up this section, cavorting while bound together in the same white hoop skirt, like a set of Siamese twins, Picasso more fully embodies the monstrous aspects feared by those who question cloning.

With earnest, sometimes desperate bewilderment, Picasso rolls around the gallery until she lies down to birth herself, sans extra head and legs. While we know the head and legs are fake from the start, Picasso nonetheless makes us believe we could be experiencing our own debilitating future; one in which we’re physically, spiritually, and emotionally burdened by the damned offspring our own hubris. As she drags herself across the floor, unburdened by her unsightly malformations but not yet free, she emanates a singular sense of self-conscious horror.

The work’s other full-company sections — Baobab Tree, Big Mama, and Bigger Mama — have the performers moving around the gallery, many of them attached to elastics that they stretch, twist, and spring away from. The first “Mama” section takes the notion of monstrosity to a higher level (literally) by connecting the clones — as if by umbilical cords — to enormous pairs of motherly arms and breasts overhead. In a reversal from the first scene, the clones are now the puppets rather than the puppeteers. As the dancers break free of their tethers, they careen through space, often nearly clashing — or not –with the audience members pressing themselves tightly up against the walls to stay out of the fray.

As I moved around the corner of one wall, to get out of the way, Barnes suddenly overtook me, pressing her body across my sweater-clad and wool-jacketed torso as if we were two tectonic plates scraping beneath the earth’s crust at midnight. I was dumbfounded and delighted. My first thoughts: Have I been cloned? Swiped? Swabbed? At home, I pulled off the bookshelf W.J.T. Mitchell’s What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images, in which he discusses the “image of the clone” as “a more subtle horror along with a more utopian prospect.” And this:

“The clone is what Walter Benjamin called a ‘dialectical image,’ capturing the historical process at a standstill. It goes before us as a figure of our future, threatens to come after us as an image of what could replace us, and takes us back to the question of our own origins as creatures made ‘in the image’ of an invisible, inscrutable creative force.”

Inter alia, indeed. Thayer, to her credit, leaves us with more questions than answers.

______________________________________________________

(For an interview with Deborah Jinza Thayer, see the 3-Minute Egg episode on Ode to Dolly below.)

Related performance details:

Ode to Dolly, the Sheep, Inter Alia, by Deborah Jinza Thayer/Movement Architecture, will be at the New California Gallery in NE Minneapolis through December 13.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre is a dance critic, arts journalist and college professor. Visit camillelefevre.com for more information.