Imaginationland

Joel Hagen responds to a group exhibition at the U of M's Nash Gallery which explores the irresistible but impossible task of recasting the timeless, inchoate wildness of natural landscapes into the mortal confines of human storytelling.

SPEND SOME TIME WITH THE WORKS IN LANDSCAPE OF THE MIND, a group exhibition now at the University of Minnesota’s Katherine E. Nash Gallery, and what resonates most is a pervasive sense of fragility, of the impermanence of the human mind in the face of nature’s timelessness. The didactic materials describe the exhibition as an exploration of “the relationships of landscape, imagination and experience in a variety of media.” Illuminating contradictions between the real and imagined emerge as a running theme in those examinations.

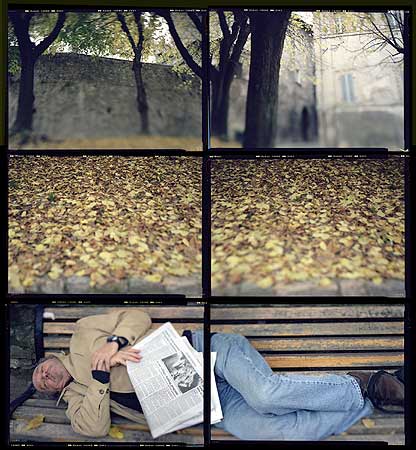

In JoAnn Verburg‘s photographic piece, Underground, a man sleeps on a park bench. At first, one assumes the man is homeless — he’s unshaven and sleeping on a park bench, covered by a newspaper, no less. However, nothing else about the man fits that assessment: his clothes are spotless; he has a nice-looking watch and a wedding ring; upon closer examination, it’s clear the newspaper isn’t used as a blanket, it’s just neatly folded reading material. Some elements of the man’s posture and surroundings – closed eyes, crossed hands, dried yellow leaves – suggest death, but that’s also deceptive: after all, leafless trees don’t die in the winter, they sleep; the man himself isn’t quite prone or lifeless either — he’s on his side, in the fetal position. Despite a viewer’s irresistible impulse to fit Verburg’s figure into a straightforward story, he resists neat narrative.

Deeper into the exhibit, Petra Spielhagen’s images similarly invite and defy the viewer’s storytelling efforts. Untitled (Dumpster Diving) is a series of four photos, for which the only given information is found in a few words on five lines next to the photos: “11:00 pm – 4:00 am / back of a supermarket / a man / a bag / a bicycle.” In the first image, you can see the shot was taken on a foggy night behind a supermarket; from a puddle of water in the paved lot, you can tell it has rained recently. There is little of “nature” to be found in this gray, iron and cement landscape. Florescent lights glow unnaturally bright in the fog — you can almost hear them hum. The series’ second photo is a largely empty scene: a vacant loading dock, a solitary bicycle; next to two bright orange dumpsters, a ghostly figure — a man, little more than a dark wisp in these images — perches on one leg holding a bag, the only thing in focus. Subsequent shots feature the same man, the same bags and bike. The figure’s purpose and story is suggestive but presented only in shadow. Looking at these images, there’s a sense of human impotence in the landscape, insubstantiality, little to indicate they’re leaving a mark.

Jan Estep‘s video installation, Searching for Ludwig Wittgenstein, takes a much different tack – looking for some trace of the human mind in the landscape, some indelible mark of achievement and insight left through the centuries in the earth itself. The work consists of mostly static shots taken during her pilgrimage to find the spot next to a Norwegian lake where Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein lived for a time in the first half of the 20th century.

The video’s palette is washed out, the dull greens of early spring, that time when remnants of fall and winter are still in evidence, rotting and brown. Regardless of the changes in the terrain, or the absence of flora and fauna present while Wittgenstein was actually living in this space, there is an expectation (rational or not) that, maybe, the next shot – or the next — will somehow capture a trace of the philosopher’s presence of mind in evidence on the land. Estep describes her walk through this place as existing on two levels: as a physical experience, informed by the actual sensory information of time and place, but also as a journey of the imagination, internally narrated and given meaning based on the site’s connection to Wittgenstein. She writes: “They both remained tense and active, and greatly enhance my experience of this place.”

This tension between imagined and actual landscapes, between the mental and physical manifestations of place, is apparent throughout the exhibition. Other pieces in the show foreground man’s imprint on nature — via wooden blocks burned with deep patterns, man-made charcoal, maps printed on used piano keys made of elephant ivory.

But in the end, all is fleeting – whether human, natural, or something in between. The landscape, at least, is malleable, better able to accommodate those inevitable evolutions. Long after the last human synapse fires, the landscape will be there to reclaim its territory from us, like mushrooms sprouting on an abandoned upholstered chair.

______________________________________________________

Related exhibition details:

Landscape of the Mind is a group exhibition on view through June 30 at the Katherine E. Nash Gallery on the University of Minnesota campus in Minneapolis. Featured artists: Laura Aguilar, Kate Casanova, Jan Estep, Jil Evans, India Flint, Anita Glesta, Richard Haas, Mark Knierim, Joyce Lyon, Ulrike Mohr, Pipo Nguyen-duy, Jane Norling, Rebecca Pavlenko, Anette Rose, Bernhard Sallmann, Petra Spielhagen, Kenneth Steinbach, JoAnn Verburg.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Joel Hagen is a copywriter and freelancer in the Twin Cities. Find him online: www.mrjoelhagen.com