I Observe You Observing Me: Dance and Performative Utopias

Reframing the concept of spectatorship: on witnessing, the impossibility of non-places, and how observation means being affected by every living being

Recently, while in a movement practice with six other local Minneapolis dancers, we found ourselves being photographed for an article, which would appear in the Star Tribune.1 This put me in a slippery place, wanting to shed my hypervigilance to the fact that where there was once just the unintrusive and unassuming gaze of choreographer/director, Rosy Simas (Haudenosaunee, enrolled member of the Seneca Nation of Indians), there was now the gaze of the two non-Native, white-bodied spectators, reporter Sheila Regan and photographer Glenn Stubbe. Of course, Stubbe’s “all-seeing eye” of the camera was present as well, recording everything it encountered into the realm of perpetuity. It occurred to me that the camera lens had an inexorable magnetism to it, generating an undertow. The current that this produced seemed too powerful to resist, and this experience created a feedback loop for me. Although this occurred over a month ago, I take some time here, to reflect and perhaps “trouble” some of the perspectives that I have long associated with experiences like these.

In the spirit of generosity and transparency, I offer the reader a bit of background here. I have dedicated many years, practicing and researching the seams between dance, theatre, performance studies and Indigenous studies. I first identify as Yaqui (enrolled, Texas Band of Yaqui Indians), but am also a contemporary dancer, performer and choreographer. I have written, interrogated, and researched the overlaps between these seemingly disparate disciplines for some time now. All this to say, this article traverses those overlaps, and is less concerned with drawing a singular conclusion and more concerned in “what happens” and “what doesn’t happen” between spaces of performance and spectatorship.

In 1965, a white-bodied settler dance artist known as Yvonne Rainer wrote about a dance she had created, titled Parts of Some Sextets, for the Tulane Drama Review. She ended the essay with the now infamous No Manifesto.2 At the time, Rainer had a strong desire to rail against the conventions of modern dance which centralized the drama of expressiveness, virtuosity, and narrative choreography. Rainer reflects: “Early on, I began to question the pleasure I took in being looked at, this dual voyeuristic, exhibitionistic relation of dancer to audience.”3 By regarding the ephemerality of dance as both difficult and elegant, Rainer and others from the Judson Church collective, including and not limited to Steve Paxton, David Gordon, Alex and Deborah Hay, Fred Herko, Elaine Summers, William Davis, and Ruth Emerson were all investigating relationships between the spectator and performer.

Anishinaabe/Ashkenazi artist scholar Jill Carter has also regarded ephemerality in dance and theatre. In Repairing the Web: Spiderwoman’s Children Staging the New Human Being,4 the power that performances can hold over an audience is explicated when Carter regards the “voluntary,” fleeting experience, which enables audiences to leave the “real world” at the start of a performance and “come back to life” once the show ends, as problematic.

Carter describes these events as “performative utopias,” in which particular social groups briefly retreat from themselves, while simultaneously enacting an ideal future. The fulcrum of this argument considers that these strategies move towards an indeterminate “non-place.” Consider Rainer’s piece WAR (1970.) Rainer utilized a devising strategy, popular by many artists at the time, in an effort to evade meaning-making and metaphor. A compiled list of verbs was culled from newspaper clippings about the war in Vietnam. The piece became a rule-governed set of maneuvers and formations in which two teams improvised game-like tasks. This anti-war dance was performed by 30 people (mostly non-dancers) at Douglass College. The words that were chosen? Infiltrate, unite, subvert. Words of war that inherently enact an ideal future. I argue here that Rainer’s work, in a desire to evade meaning-making, still calls upon a violent past which relies on military terms to create a performative utopia, or a “non-place.”

Yet for Indigenous Peoples, there are no “non-places.” There are only actual places, which are rooted in the traditional lands of the people, the lands in which so many were forcibly relocated. The same is true of the Peoples’ histories, languages, metaphysical understandings, spiritual practices, and traditional knowledge systems. We can never escape our relationship to these actual places, nor would we want to. It could be said that the ability to create performative utopias are limited to those who believe that their ideas can exist outside the realm of the natural world.

Nonetheless, Rainer’s contribution to the field of dance and spectatorship is staggering, especially considering her Trio A (1966), The Bells (1961) and WAR (1970), which have all been regarded by white-bodied theatre scholars as crucial interventions which reconsider the perspective of the viewer, strip the human body as meaning maker and draw attention to the fact that the very act of theatre comes down to the “irreducible fact that one group of people is looking at another group.”5

I am struck here by Rainer’s quote, pointing to the simultaneous fluidity and duality of spectator and performer. I am reminded of the term spect-actor, created by Brazilian theatre practitioner, drama theorist, and political activist Augusto Boal. The story goes that in a post-performance “talkback,” following a play that Boal directed, an audience member became outraged when an actor could not understand their suggestions. They then went onto the stage and demonstrated what they meant, to the audience, the actors and to Boal. This became the birth of the spect-actor (not spectator.) Boal began to invite audience members to make suggestions for change onto the stage, as a way to demonstrate their ideas. He discovered that this participation enabled audience members to become empowered. They now not only imagined change, but began to actually practice and enact that change collectively. These spect-actors becoming empowered began to generate social action as a new kind of theatre, which became a vehicle for grassroots activism. This supported Boal’s claim that “theatre is not revolutionary in itself but is rehearsal of revolution.”6

The space between theatre and dance, I realize, is fraught. I am reminded of white-bodied scholar Rosemary Candelario’s words, describing Japanese performers Eiko & Koma and the difference that lies between these two disciplines: “Eiko & Koma do not represent mourning, I argue; they do it. They do not just represent new kinds of alliances with nature and across differences; they generate them. Very slowly.”7 Candelario’s words here delineate the boundaries between the “acts” of theatre, which create meaning by showing, and the “being-ness” of dance, which generates connection through experiential becoming.

White-bodied theatre scholar Peter Brook has long held the opinion that the spectator is the “assistant” to the performer. Brook claims that the act of repetition transforms into representation, especially within the visual realm. In other words, the audience must agree that a repeated act holds significance, and that significance can then signify something. The very act of theatre relies on the audience’s belief in transubstantiation (the conversion of the Eucharistic wafer and sacramental wine into the body and blood of Christ at consecration.) Brooks continues by saying that

“Then the word representation no longer separates actor. and audience, show and public: it envelops them: what is present for one is present for the other. The audience too has undergone a change. It has come from a life outside the theatre that is essentially repetitive to a special arena in which each moment is lived more clearly and more tensely. The audience assists the actor, and at the same time for the audience itself assistance comes back from the stage.”8

This concept, forwarded by Brook, however, seems to only contribute to the isolation of the audience. The participants in this scenario become less than human, for it is through that complicit assistance that they relegate themselves to an unequal plane, which pits them as the audience against those who have been accepted as the actors. The danger here is that the audience members then become the passive victims of images co-opted and portrayed by the ruling class. Brook proposes that the spectators must delegate power to the characters, either to think or act in their place, and that this is the site for “transformation.” This is a scenario where the audience is not free to think and act for themselves but must do so in service of the performance. I also wonder if this is not just another construction of a “performance utopia,” where an ideal future is enacted through pretending, through play, through a “non-place.”

Algonquin Anishinaabe and settler Canadian scholar Lindsey Lachance describes “witnessing as research” as an emergence of experiences which come from heart, body, mind and spirit. “Working this way allows my responsibilities to the Indigenous theatre community to be upheld and reminds me that the work I am describing is not a distant theoretical or metaphorical theory, but is my lived and honest reality.”9 As I have spent much of my life (so far) devoted to the multiple practices of dance, theatre, and scholarship, it is only fitting that I call upon my own witnessing as research. I pivot here, as a dancer, who has witnessed while doing. I now invite you, the reader, to move with me, the writer, from the discussion surrounding the phenomena of spectatorship, performance, and observation to a revisitation. A glance back to that particular day in September 2021 when the reporter, the photographer, and the camera were present. A few months back from this present moment, which have now become past moments, where I now commit words to this article.

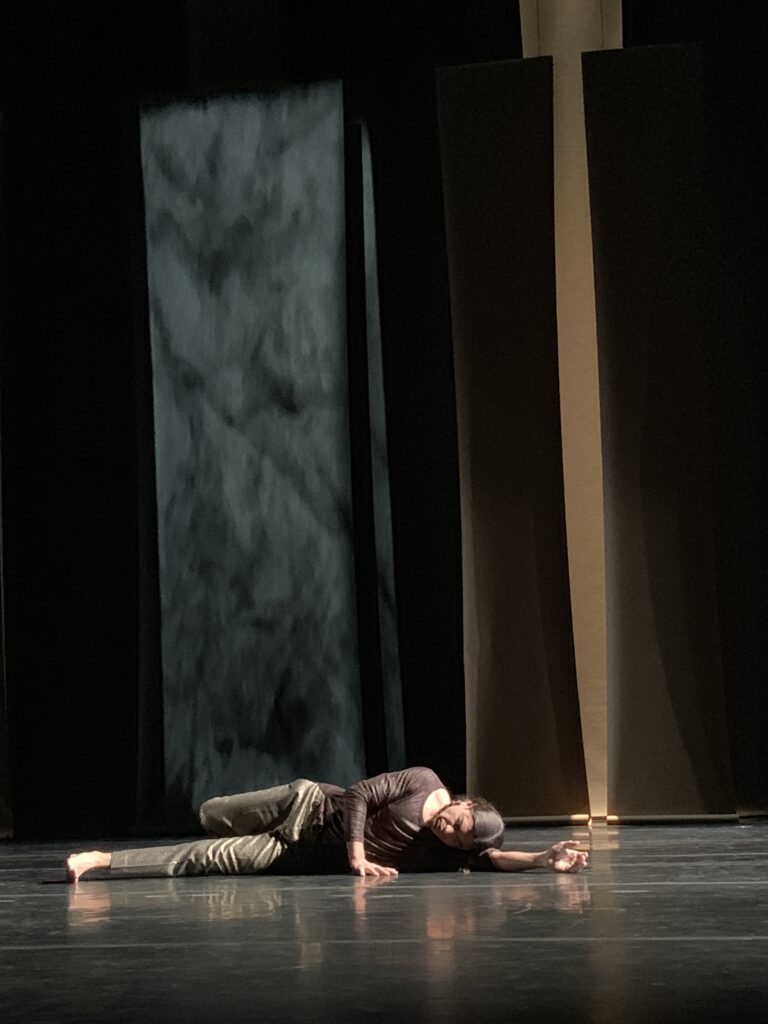

Alone, but with my thoughts of who you are: the Spect-Actor and Quantum Interference

As I found myself in the Northrup King building, in Space 331, on September 24, 2021, I wanted to remain unaffected by the observers in the room, as I wanted to stay true to the form which we as a group had meticulously established three months before. I found myself drawn into an inextricable dilemma: was I spect-actor or were they? Because I was watching the three of the observers watching the six of us, as well as watching the six of us watching each other, while watching the three observers, my mind began to swim. As we began our practice, I considered the prompts given to me by Rosy Simas. What does it mean to find rest, refuge, to condole? What does it mean for me to do this in a shared practice with others? I wondered what the shape of my body looked like and I wondered how the shadows appeared on the walls when the sun streamed through the windows, warming my muscles and skin. How is my brown skin read in this space? At this moment? Was I too close to the camera, eclipsing the other people in the space? Was I turning my back away from the camera and the photographer, as an act of refusal?

As I became more immersed into the creative process, I began to close my eyes, and could feel the fabric of my rehearsal clothes move against my skin. I could feel the floor with my feet and the air move through the room. I moved through space, and crossed a threshold, entering an internal space which allowed greater generosity, for even deeper attenuation. In this practice, I am tuned into the multiplicity of overlapping senses, to the currents of energy within the room, to the other humans in the room, and the non-humans outside of the room.

How do I consider the spect-actor and share my experience without “performing” that experience? What does it mean to truly feel what I’m experiencing, moment by moment, without the unnecessary act of heightening the state of that experience? Whether my eyes are closed or my eyes are open, I am aware of the spect-actor and invite them in, through my eyes. This single-mindedness allows me to escape the doubts that can occur for performers in regards to the spect-actors: that no one cares, or that they care too much, that they love what we’re doing, or that they hate what we’re doing. Yet, I am also aware that the very presence of these spect-actors have inherently changed not only what I am doing, but what the other five performers are doing. The reality is, we all are in a relationship, whether we’d like to admit it or not.

I liken this to the observer effect in quantum physics, or any disturbance that occurs within an observed system, through the very act of observation. This is when the instruments required to measure phenomena alter the very state of that which they are trying to measure. An example might be checking the pressure of a bicycle tire with a tire gauge. When engaging the tool, some of the air escapes through the valve of the tire, thereby changing the pressure of the tire. Similarly, it is not possible to see any object without light hitting that object, and causing it to reflect that light back to the observer. While the effects of observation could be said to be negligible, the object still experiences a change.

According to white-bodied, American feminist theorist, Karen Barad:

“Practices of knowing and being are not isolable; they are mutually implicated. We don’t obtain knowledge by standing outside the world; we know because we are of the world. We are part of the world in its differential becoming.”10

To put it simply, I do not stand apart from the natural world. I am a part of it. As my son Max once eloquently stated when he was eight years old, “Dad, everything on the Earth is made up of the Earth.” It is not merely coincidence that my lungs look like trees and that my bloodstream looks like the rivers and streams of the earth. My body follows the same ebb and flow as the natural world; the tide and the wind do not just flow around me, they flow through me.

Even through the greatest, most capacious desire to forge an ideal future, which might somehow magically place me outside the realm of nature, I cannot overcome the irrefutable reality that I am enveloped within and throughout nature. I am inextricably bound to you, as performer to spect-actor and vis-à-vis, and from living being to living being. My body is not just a sum reflection of sun, clouds, moon, flowers, trees, or river, but is an iteration of the same material. As a human, I do not simply “show” my experiences to you, as an isolated event, through the creation of a “statements” about them. I generate connection through our collective experiential becoming and I am affected by every living being around me, including you, just as you are affected by every living being around you, including me.