Everything Is Everything, or How Black Women Will Survive the End of the World

Terrion L. Williamson, who serves as Assistant Professor of African American and African Studies at the University of Minnesota, and is the author of Scandalize My Name: Black Feminist Practice and the Making of Black Social Life, expounds here on Barbara Christian's "intentional privileging of black women's lifeworlds" and celebrates the fugitive practices and lives forged and cultivated by black women every day.

won’t you celebrate with me / what I have shaped into / a kind of life?

Lucille Clifton, “won’t you celebrate with me”

What I write and how I write is done in order to save my own life.

Barbara Christian, “The Race for Theory”

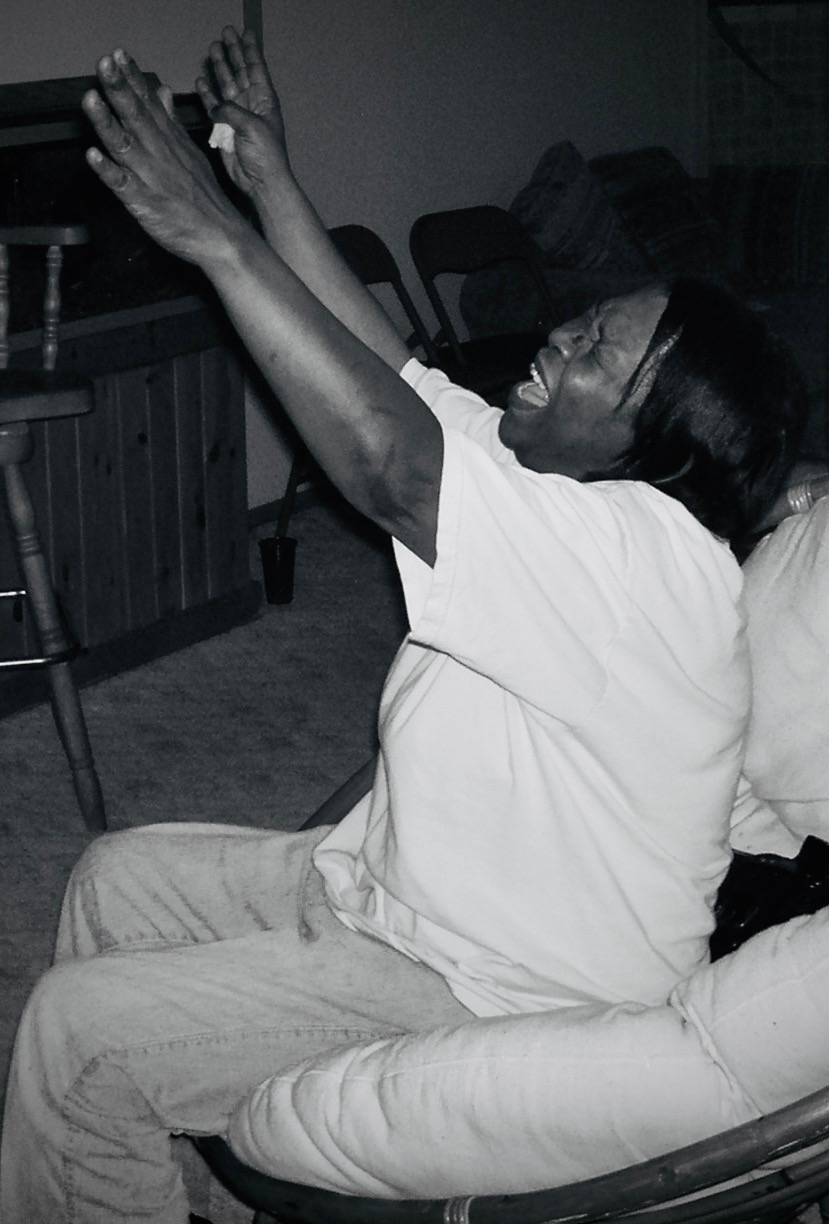

For Mama, whose pain is unrelenting, but who bears it with more grace than we deserve. For Alyssa, in the hospital right now. For Sweet, who is awaiting the news. For Connie, who got three kids and only herself to carry the load. For Carmea and Tyrhonda, who just had to mark one more fucked up anniversary of their mother’s being taken. For Lauryn, who needs to know how much she is loved. For Christine, who has learned to endure. For Ellanna, because she is eight now. For Anitra, because she is learning to exhale. For Talita’s mama, because she is grieving still. For Charisma&Shanika&Champagne&Charniece&Brandi, because they must know that they, together, are the secret to black girl survival. For Kellee, who entered into motherhood, like so many black mamas, in the hardest of ways. For Grammy, who lingers still.

For Ntozake, who wrote for us.

I began my writing career as a very young girl. But in those heady days, I did not think of my writing as aspirational or careerist, of course. Writing was for me then wholly unencumbered from the logics of labor. The plot outlines and snatches of conversation and short stories that I wove together were replete with tales of black girls in relationship with and to other black girls and, occasionally, boys and other people who were not girls. Always a realist, I didn’t spend much time on the princesses and fairy tales and Disneyesque dreams that are often ascribed to little girl life (Who had ever heard of such a thing as a black princess anyway?) but was instead consumed with the mundanities of church, home life, and, especially, school. That is to say, what I know now that I might not have known then was that my writing was a way of working through some of my stuff, it was where I went to figure out myself and a world that I often found startling and incomprehensible.

Just over thirty years ago, the eminent black literary scholar Barbara Christian threw down the proverbial gauntlet when she took to task what she called “the race for theory,” an enterprise she opined was instigated by Western philosophers and literary critics whose own work was often “palled, laden with despair, self-indulgent, and disconnected.” Theory of this sort had become an academic “commodity” that enabled the continued disregard of the creative writing and writing practices of contemporary black women writers, in particular. The point was not that theory should be per se outlawed, but that the institutional power brokers, whose ranks sometimes included people who should have known better, had essentially ghettoized the forms of organic theorizing engaged in by black folks and other minoritized populations in their riddles and proverbs, their dynamic storytelling, and their creative wordplay. For Christian, the power of literature was that it had the possibility of “rendering the world as large and as complicated [and] as sensual” as many of us know it to be, and one of the imperatives of black women’s writing was that it allowed black women to “pursue ourselves as subjects”—a feat of no small significance in the annals of intellectual history.1

The spate of criticism Christian received after publishing “The Race for Theory” has been well documented and I do not mean to rehash the terms of that debate here.2 Instead, I am interested in how Christian’s intentional privileging of black women’s lifeworlds in her critical practice resonates with Lucille Clifton’s invitation to celebrate “a kind of life” that is the unique purview of black women. That is to say, black women who labor, even if not in the academy, and black women who theorize, even if not according to the protocols of academic discourse, all know something about what it means to have to shape a kind of life out of the barest and most elemental of materials.3 If it is the case that black women take their own lives at lower rates than other demographic groups,4 it is certainly not because we suffer less or have less to mourn. Either you know the stories or you should. But from the earliest days of our arrival we are trained in the arts of keep keepin’ on and gotta make a way. There is so much to do, so much to be. It does not mean that our wounds are any less deep, that our pain is any less sharp, that some of us, too many of us, are not struggling, just barely holding on. But we are trying to find ways, with our voices and our bodies, through our stories and our songs, to shape our lives, for as long as we have them. We must celebrate our kind of lives, because they, we, embody what has been refused to us. We, are the essence of fugitivity—escapees, skilled in contraband, who have mastered the art of furtive flight.

Near the end of Toni Morrison’s 2012 novel, Home, the character Ycidra, who is referred to by everyone except her mama as “Cee,” spends time healing from a vicious assault on her body “surrounded by country women who loved mean.” It is in the presence of these black women who “practiced what they had been taught by their mothers during the period that rich people called the Depression and they called life,” that Cee begins to find herself anew, begins to understand what it means to craft a livable life as a black woman. Nowhere is this more evident than when she contemplates how she came to be in her predicament:

As usual she blamed being dumb on her lack of schooling, but that excuse fell apart the second she thought about the skilled women who had cared for her, healed her. Some of them had to have Bible verses read to them because they could not decipher print themselves, so they had sharpened the skills of the illiterate: perfect memory, photographic minds, keen senses of smell and hearing. And they knew how to repair what an educated bandit doctor had plundered. If not schooling, then what?5

What Cee comes to know is that the black women who become her caretakers, like the black women who took care of so many of us, were purveyors of organic intellectualism, liberated from the constraints attendant to academic convention and the prejudices of the institutional elite. This is not to exalt illiteracy but is to foreground another way of reading, a “not-yet-finished” way of knowing that does not presume to know the answer to all things for all time but knows just what we need right here, right now. It is an epistemological practice grounded in the extraordinariness of a black sociality that is determined to live and not die—a protocol of difference that understands that “blackness has always been beyond.”6

Then what.

As a young black girl, I used literature—my own writing and the voracious appetite for other people’s writing that was cultivated by way of my mother—as a way of exploring the world, of learning something about myself, and, as Barbara Christian puts it, for ensuring that “whatever I feel/know is.” As an adult black woman who is also an academic, literature still serves this purpose in my life, but it is an increasingly difficult endeavor in the face of “publish or perish” standards that, thirty years hence, still often do not value the cultural contexts out of which my work, and so much work like mine, emerges. Writing to save my own life, indeed. The point of the telling is not that my story is unique, but that it is so very mundane. From little black girls, to fully grown black women, to allied black folks who don’t identify as either girls or women but who experience the struggle intimately—we know something about what it is to save our own lives. It is why we wail with Aretha and Mary and them. Why we continue to hold space for those deemed least among us. Why, for us, the election of 45 was neither the beginning nor the end, but merely the continuation. Why the economic “crisis” was same shit, different day. It is why Tarana and NO!7 came long before the conglomerates were paying attention and why it was Patrisse and Alicia and Opal who insisted ya’ll know that we know that black lives matter. Why we insist we are magic. It is to say, we have shaped a radical discourse out of illegibility and have learned to ask the questions that are central to our survival, even if they are not the ones our critics want asked—or answered. That, if nothing else, is cause for celebration.

This article was commissioned and developed by Mn Artists guest editor Chaun Webster as part of the series Blackness and the Not-Yet-Finished.