Dome Light: At Home with Artist Martin Woodrich

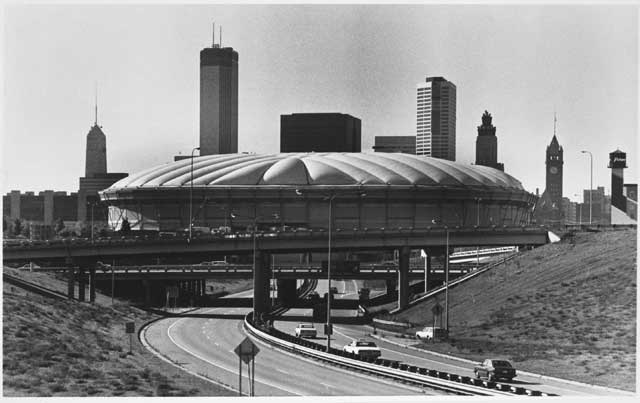

Andy Sturdevant profiles a prolific community-supported Minnesota artist noted more for his unusual home than for his moody paintings: the Metrodome's artist-in-residence since the sports facility's opening in 1982, Martin Woodrich.

IN THE EARLY MORNING HOURS OF DECEMBER 12, 2010, artist Martin Woodrich was asleep in his small, modestly furnished one-bedroom apartment in downtown Minneapolis. He’d been home all evening, working in his adjoining studio in preparation for an upcoming retrospective show. Like most Minneapolitans, he was glad to be indoors, sheltered from the blizzard that had dumped over three feet of snow on the city in only 24 hours. After a few hours of working on a new painting, Martin soaked his brushes in odorless thinner, hung up the battered old baby blue Twins t-shirt he often paints in, and went to sleep around 11 p.m. At nearly 5 a.m., he was awakened suddenly by a thunderous noise overhead, emanating from just outside his studio, which was quickly followed by what sounded like an avalanche.

“I had a sickening feeling,” he says now, months later, from his temporary studio space across the river in the Marcy-Holmes neighborhood. “It’s like I heard that sound, and I knew exactly what it was — like I’d been expecting it.”

The sound that woke him was the roof of the building Martin had lived in since 1982 collapsing under the weight of the snow.

The building Martin lived in is the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome.

Martin Woodrich has been artist-in-residence at the Metrodome since it opened in 1982. Although he’s little known to the public, for nearly three decades Woodrich has maintained a living space as well as a small studio near Gate H, adjoining the terrace suites right above sections 138 and 139. In the twenty-nine years he has worked in the Metrodome, Woodrich has seen two World Series, one Super Bowl, nine NCAA tournaments, and many changes in the Downtown East area. He is primarily a painter, but apart from the thousands of paintings he has created in that time, he is also responsible for countless drawings, sculptures, prints, photographs, videos, installations, performances, and even a few poems. The Metrodome is one of only four stadiums in the United States that maintains a year-round artist-in-residency program, the other three being Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, Candlestick Park in San Francisco, and the New Meadowlands in New Jersey. And Woodrich is the only artist-in-residence in America to have remained with a stadium since its inception.

He is now 58 years old, and since the Twins’ move to Target Field in 2010 and the Dome roof’s collapse, his future as an artist is more uncertain now than it has ever been. Ironically, when the roof fell through, he was putting the finishing touches on the first major retrospective of his work since the 1980s, opening at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts later this year. By the time the retrospective opens in November, he may no longer be working in the building that has been his home and his muse for over a quarter-century.

“Things change,” he says, chuckling. “The last year has been so crazy. Who knows what might happen? That’s the Dome. The Dome is a crazy place, so I guess that’s part of the deal.”

How did Woodrich come to make his career in this way? Before telling that story, it’s useful to know a little bit about how the Metrodome came into being in the first place. The two stories are closely entwined.

The battle over the stadium was, as many Minnesotans will remember, a contentious one. By the time Governor Al Quie signed the bill for a $55 million domed sports stadium in downtown Minneapolis in 1979, the battle over funding and site selection had gone on for ten years. As a condition of the facility’s funding through a special tax district in the area, the Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission insisted a small fund for an artist-in-residence program be built into the deal, in order to “facilitate and support the creation of a downtown-wide cultural district.” Downtown revitalization proponents had lobbied tirelessly for this condition to be added to the bill, modeling it on a successful similar program in New York City in the 1960s. When Shea Stadium opened in Queens in 1964, a few thousand dollars were drawn from the stadium’s operating fund to support a small residency program on-site. The abstract expressionist painter Philip Guston lived and worked out of a studio at Shea in the mid-1960s, giving the new suburban facility a certain cosmopolitan air that investors and realtors found highly attractive. (In retrospect, Guston’s abstract work during this period was perhaps the least distinguished of his career, and some art historians have suggested his now-famous return to representational painting in the late 1960s was a direct result of his frustrating experiences in the Shea Stadium residency program.)

So, it was decided that the Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission would adapt an artist residency program for the Metrodome. A yearly fee of $20,000 — drawn from the stadium’s general operating fund, ticket sales, and donations from local foundations — was arrived on as a reasonable accommodation for the selected artist. And it is that $20,000 annual stipend that Woodrich has lived on each year since 1982.

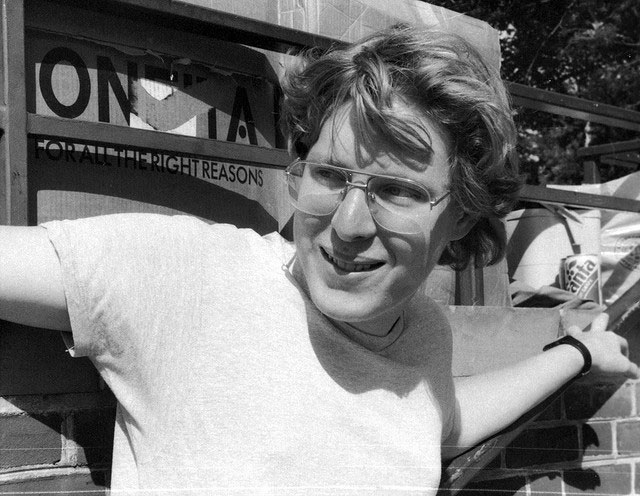

In 1982, Woodrich was a twenty-nine year old painter living in an illegal walkup in the Warehouse District, about a mile northwest of the Metrodome (and, ironically, now the home of Target Field). Born in Judson Township near Mankato in 1953, he had moved to the Cities to attend the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, where he graduated with a degree in painting in 1976. He was also awarded one of the first Jerome Fellowships, in 1981. It was possible for an artist to eke out a meager living on private and corporate sales during that time, and Woodrich sold work to the likes of First Bank System (known for their daring contemporary art collection). He also exhibited in some of the most respected galleries of the time – Jon Oulman, Thomas Barry, Medium West. He had a reputation as a gregarious, witty personality in the art scene, able to charm patrons and his artist peers alike.

______________________________________________________

“It’s like Gaugin in Tahiti, or the abstract expressionists in the East Village — it’s the surroundings that make the work, and the place I experience my life. It just so happens that, for me, that place is a stadium with a fiberglass roof.”

______________________________________________________

“You were always hustling in those days, always looking for new ways to get your work supported,” he says now. “So when I read about the opportunity for the residency at the new stadium, I thought, Sure, what the hell? My girlfriend had kicked me out, and I didn’t have anything going on, so it seemed like it might be a fun way to spend a couple of months.”

Woodrich was a casual sports fan, but certainly not an obsessive. “My dad took me and my brothers up to Met Stadium to see the Twins in the ’65 playoffs,” he remembers. “I think I got Earl Battey’s signature somewhere. It was fun, but it wasn’t like, Shit, I wish I could spend all my time at the ballpark.” He also remembers tailgating at the old Met with his father and some family friends before a Vikings game in the late 1960s, though when pressed for details, he just shrugs. “I mean, it was fun, but it was just being with my brothers and my old man, you know? I was probably sitting somewhere drawing anyway.” So why accept a residency in a stadium, where one assumes you’d be eating, sleeping, and breathing sports?

“Art comes from anywhere, you know?” he tells me. “You never know what is going to spur your next project. I mean, it’s not like they were looking for [famed sports painter] LeRoy Neiman to sit around and make shitty portraits of [Minnesota quarterback] Fran Tarkenton. They were looking for an artist that could handle themselves and make some interesting work and not spook the bigwigs, or seem like a hack. You know, not seem like a rube when the Yankees were in town or whatever.”

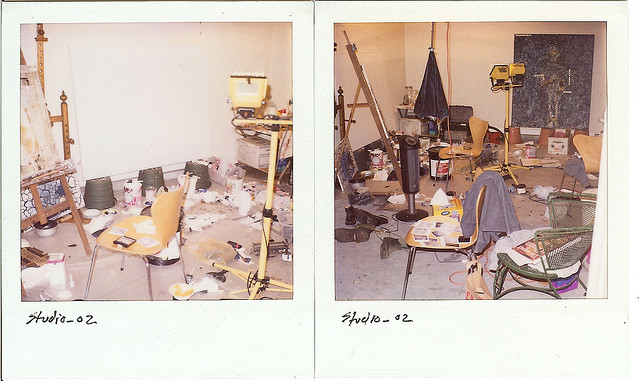

Woodrich applied for the position, and after a few interviews and showing stadium officials his studio above Moby Dick’s on Hennepin (“they weren’t real impressed with the place,” he deadpans, “because some wino tried to stab them on the way up”), he was named the facility’s artist-in-residence in March 1982, a month before the Metrodome opened. By the first Twins game in April, he had moved in. He’d unwittingly entered a phase of career that, more than two decades later, he would still find himself in the thick of. “I never planned to stay this long,” he says. “After six months, it was going well, and I asked, Well, do you guys mind if I reapply? I like the light in here. They said, Be our guest. And I just kept turning out a lot of work — a ton of work. And I just reapplied every six months until, I think, 1985 or so.” At that time, Woodrich met with the leadership of the Facilities Commission, and all parties agreed they were happy with the results to date, and it would be best to extend the residency through the end of 1990. Eventually, that became the 2005 season, when the Twins’ lease was up. Since then, like the building’s other tenants, he’s renegotiated year-to-year.

I tell Woodrich I still don’t get it. Why the Dome? Why commit to so much time to this place? He thinks for a second, and then asks me if I’ve been the Dome myself. I say of course, many times. “OK, then,” he clarifies. “You know it’s not just sports, then, right? You know it’s the people that are in there. It’s the way the doors suck you out when the vacuum is broken as they open, right? It’s those little details. Plus, it’s empty half the year, anyway — all that space. I’d just wander around during the off-season, or when the teams were on the road, looking at the ceiling. Plus all those old folks roller-skating and mall-walking. Or the Monster Jams. Or the Hmong New Year’s. Always something interesting happening. To me, it’s like Gaugin in Tahiti, or the abstract expressionists in the East Village — it’s the surroundings that make the work. It’s the place I experience my life. It just so happens that, for me, that place is a stadium with a fiberglass roof. It’s so unlike anywhere else in the world.”

Woodrich’s work is in storage now, away from the Metrodome — it was moved after the roof collapsed, and, fortunately, none of it was damaged. We drive from his studio in southeast Minneapolis to a storage facility on Lake Street, not far from the Institute of Arts. Walking through the rows of his paintings and drawings, one is struck by how little his work seems to do with football or baseball, or even the Dome itself. Not one sports-related image appears in the lot of them. Much of the work is huge, atmospheric abstract paintings — neutral tones, with a static quality that seems oddly familiar to anyone that’s spent an evening under the fluorescent lights at the Dome, looking down at the artificial turf. There is something unreal about this work, as there is about the Dome. Some of the pieces incorporate an odd plasticized fabric, and even neon lighting elements. Much of the work puts one in the mind of a bizarre mash-up of Dan Flavin and Agnes Martin. Woodrich is a formalist; his interest is in light, form, and texture. These interests were clearly forged, at least in part, by spending the last 25 years living underneath the Dome. One thinks back to Woodrich’s darkly humorous explanation for his attachment to the place: I like the light. To spend time with a Woodrich painting is to feel surrounded by forced air, strange angles, and a pervasive artificial glow. It is unsettling and yet somehow deeply nostalgic for the very recent past.

“These won’t be in the show, probably,” he smiles wryly, showing me a portfolio of life drawings. It’s a ream of beautiful charcoal sketches of nude men, some with very familiar faces. “Let’s just say that after twenty years, I was able to convince the guys to let me use their locker room showers as a life drawing master class.” A noted Gold Glove-winning Twins outfielder of several years ago, totally naked, stares back at me with a serene expression on his face.

The only other work that seems to explicitly reference the building itself is a book of gouache paintings. It’s what he calls a “portrait series” of every seat in the Metrodome. Thousands of blue seats, almost all 64,111 of them, are painted quickly but meticulously. Each seat number is written underneath in a clean, precise hand. The variations between them are subtle to the point of being indistinguishable.

______________________________________________________

To spend time with a Woodrich painting is to feel surrounded by forced air, strange angles, and a pervasive artificial glow. It is unsettling and yet somehow deeply nostalgic for the very recent past.

______________________________________________________

Since the Dome’s collapse, Woodrich has been living and working off-site as the stadium is renovated. The studio in the Metrodome stands empty. Fortunately, it is undamaged, but not suitable to live in for the time being (“which,” he notes, “is completely absurd — the roof got torn up in ’81, ’82, and ’86, and they got it together again in no time”). He says the Facilities Commission is offering to pay for his temporary lodgings through the end of 2011, but, he claims, “They say I should be prepared ‘to look at the arrangement a little more closely, going forward,’ whatever that means.” He knows his time is almost up. “I think that in five years, there won’t be a Metrodome anymore. The Twins are gone, and the Vikings will be, too, at some point in the near future. I can’t imagine another artist-in-residency program. I’m not sure what’s next.”

A spokesperson for the Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission wouldn’t comment on the future of the residency program, other than to say this: “Woodrich has been a valuable voice in Minnesota arts for the past 25 years, and we’re proud of the work we’ve done together.”

The retrospective at the MIA in November will certainly help spur interest in Woodrich’s expansive body of work, and he says he’ll certainly be appreciative. He claims he’d spoken to “a major domo” at Target, and the possibility of an artist-in-residence program for each individual Target retail location is something that may be in the works. “It wouldn’t be the same, of course,” he says. “And it might not even be for me. There are younger artists out there that could use the leg up. The scale isn’t there, for me, with a Target store. I mean, sure, it’s big. But it just doesn’t have the … grandeur of the inside of the Dome, if that’s the right word. The Dome was the last of its kind. People just don’t really appreciate that kind of experience anymore.”

What he will do away from the sterile otherworldliness of the Metrodome is not yet apparent to him. He looks out the window of his studio where we’re sitting, out onto the street. He squints as the glare of the sunlight hits the white piles of snow on the street corners, reflecting back through his window.

Woodrich smiles ruefully. “This sounds crazy, but it feels weird to be outside. The sunlight, the air, the dirt — just doesn’t feel right. I just feel assaulted, you know?”

______________________________________________________

Uncovering Martin Woodrich: Paintings, 1982-2010 opens at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts on November 3, 2011.

For more information about this artist, his work, and the upcoming retrospective, click here.

Related articles: “Farm Accident: A Secret History” and “Boheme Maximale: The Untold Story of One of Minnesota’s Greatest Art Treasures”

______________________________________________________

About the author: Andy Sturdevant is a writer, artist and arts administrator based in South Minneapolis. He is the host of Salon Saloon, a monthly live-action arts magazine held every fourth Tuesday at the Bryant-Lake Bowl. The topic of the upcoming April 26 show is former President Bill Clinton. On June 4 and 5, you will be able to find him on the Mississippi Megalops, a riverboat project created with Works Progress for the Northern Spark Festival.