Building a House for the Twilight of the Gods

There are weird buildings all around us. They are our megachurches and art museums, our sports stadiums and soaring centers of commerce. What cultural myths do we encode in the architecture of these landmarks-by-design?

A strange building is rising in downtown Minneapolis. Or at least it seems strange given the skeleton currently in place. Weird buildings are nothing new for the city. A number of them have gone up in the last decade or so: the new Guthrie, the new Walker; the Minneapolis Library is a little weird, too. And the godfather of Minneapolis’s weird buildings, the Gehry-designed Weisman Museum on the University of Minnesota’s East Bank campus, has been around for over 20 years now. They all seem to be informed by a latent Futurism, like shiny, forward-looking sets from a science fiction movie. (The Guthrie always strikes me as Darth Vader’s vacation home and the Walker is, of course, a giant robot head.)

They are all landmarks by design, buildings intended to overwhelm the landscape surrounding them. The “weird” building’s design is not meant to blend into the background (which in some ways makes these structures very non-Midwestern in character, unlike the residents coming and going in them, dressed in black parkas and jeans, trying to get through the day unnoticed). Far from nondescript, these buildings scream out to be remarked upon (again, unlike the average Minnesotan). Their design elements are as often as not superfluous – features built to impress, with little concern for discernible function. The design of such buildings exists in the realm of the ideal, the ideological; their makers want to influence the way we think–about buildings, about ourselves, about civilization–as much as the way we use the structure. Such buildings challenge our assumptions about how we imagine the world works and how we interact with its structures. Which is what weird things do in general — they pull us out of our comfortable material routines and challenge our mental habits.

Not-weird condos, under construction in downtown Minneapolis. Photo by the author.

From where I live, I can see a new one of these buildings going up, and I can also see other, far less weird buildings being built downtown, as well. The not-weird buildings have 90-degree angles; they are clearly destined to be large rectangular boxes, stable and simple: they will have long, straight hallways and square rooms and, once the off-gassing is done, you will barely notice them as you pass through. That is, these not-weird structures will be perfectly Midwestern upon completion; even now, I barely notice their ongoing construction. But, again and again, my attention is drawn to this strange, asymmetrical giant triangle perched on the horizon. It looks like a mistake, a disaster. It looks like they are building some kind of downtown space port.

Still from Contact, 1997, courtesy of Warner Bros.

I look, and imagine it could be a device for accessing other dimensions or, perhaps, another part of the universe, as seen in the movie, Contact (in which Jodie Foster is rewarded for a lifetime of searching the skies with an 18-hour dream-like and perhaps imaginary visit to an alien planet where she talks to her dead yet somehow reassuring father, which is enough to keep her going). Its shape also calls to mind the time portal seen on the original Star Trek series (Episode 28, “City on the Edge of Forever”, where Kirk has just watched a woman he loves die, even though he could have saved her but did not in the understanding that the present depends on the past remaining the same, the episode ending with Kirk saying, “Let’s get the hell out of here,” and that’s when everything changed, when you could start almost swearing on TV and when science fiction became the primary source of existential texts in American television culture, replacing the Western).

Weird building-in-progress in downtown Minneapolis. Photo by the author.

What they are in fact (or, at least, claim to be) building, though, is the so-called People’s Stadium, the new home of the Minnesota Vikings football club. And in its current state, it appears to be one of the weirdest sports stadiums to date. Sure, Barclays Center in Brooklyn, from the outside, looks weird at first glance, but from above you can see it is mostly a very traditional arena with an eccentric superstructure put around it. Even so, standing outside on the entry plaza, to a casual passerby that superstructure reads “weird” enough that it seems very much like an alien mothership has landed on Atlantic Ave — which, for me, is a delightful and satisfying thing to happen when encountering a building.

It’s the kind of structure that demands one take notice, stop, and ask questions. What the hell is this thing? Can buildings really look like this? If so, why do most of them look so similar, with all those obvious right angles? Spoiler alert: because it’s cheaper, that’s why; Barclays Center, weird as it wants to be, was greatly scaled back from its original Gehry design (Frank Gehry being perhaps the most famous architect of weird, and thus really expensive, buildings). In the end, Barclays Center’s eccentric superstructure is but a compromised homage to Gehry, whose designs were abandoned, along with most other aspects of the Atlantic Yards complex originally proposed for the area (and in its place are some of the most ugly, boxiest, brick buildings you will find in any American city. I’m talking to you, Atlantic Center New York State DMV).

On one level, it seems building an eccentric building for any sport would be a challenge because of the need for a standard-issue play area at its center, a soccer field or hockey rink or what have you. Every sport has extremely strict rules players must follow; everyone has to do the same thing, in part, because this makes the game easy to measure and ensures its outcomes are comparable across a number of individual competitors’ events. Thankfully, architecture need not follow such rules. Architectural design can introduce elements of the unnecessary ideal to the material world, incorporate illogical and individualistic dreams into our social waking life. And so, in looking at the ongoing construction, I began to wonder if the new football stadium was somehow going to continue and be a part Minneapolis’s weird building aesthetic.

It costs money to build dreams, of course — a lot of it. And this is certainly the case with the new Vikings stadium (for which naming rights have not yet been secured). And it strikes me that, if you needed to secretly build a dimensional portal or time machine, one way to raise the vast amount of money required without undue notice would be to do so in the guise of building a sports facility. But even at a billion dollars, the Vikings’ new home is far from the most expensive stadium ever constructed. That honor goes to MetLife Stadium, home of the New York Jets and Giants — and that building’s not weird at all, just a big empty bowl, and so, in my estimation, an utter and complete folly.

But perhaps stadiums should be models of boring efficiency to highlight the simple, dualistic competitions they host. Perhaps the eccentric should be reserved for museums and theaters, where anything can happen. The association of unorthodox architecture and art spaces, in particular, is unsurprising. After all, art museums are the places we go to explore the limits of our imagination. Profoundly weird buildings (the sort with bombastic, unnecessarily attention-demanding design) got their start, though, with the church: magnificently strange cathedrals, built on a grand scale and ornate with fanciful details, expressly inviting us to consider realms beyond the material.

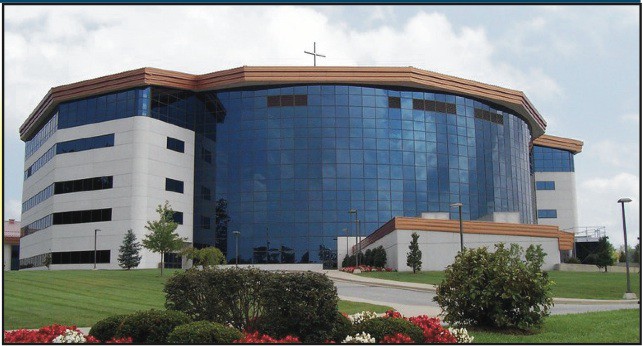

In looking at buildings for this piece, I’ve been struck by the design similarities shared by several recently built megachurches and the new Guthrie (particularly once you remove the churches’ “steeples” from view). There’s some irony in the resemblance, in the idea that contemporary sacred spaces might borrow from the eccentricity of modern art, given the church’s affinity for the absolutes of traditional dualism and art’s room for relativity to run wild.

The Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California is another striking piece of contemporary sacred architecture, eccentric looking but with a very clear and traditional ideological function (which is likely why the Catholic Diocese of Orange bought it when Crystal Cathedral Ministries went bankrupt). It’s interesting, though, how this modern cathedral borrows heavily from the design of contemporary glass skyscrapers — centers of earthly power. And, really, this gets at the larger trend in contemporary megachurch design: making them look like arenas and malls. It’s easy, in fact, to see the influence of material, consumer culture on contemporary houses of worship: they’re increasingly giant, ugly boxes of glass and poured concrete. (And like their retail counterparts, these big-box churches are, more and more, putting small, mom-and-pop houses of worship out of business.) Clearly something has happened to our gods. Unlike the transcendent divine housed in medieval cathedrals, today’s Heavenly Father is apparently more at home in something like a giant theater, an outsized yet economical room with clear sight lines, even from the cheap seats. It’s only fitting that a house for the god of the prosperity gospel would reinforce its congregants’ faith in the practical pleasures of the material world rather than inviting their imaginations to consider the mystery of some ineffable, heavenly realm. Such a god is, first, an agent of material happiness in the here and now and His (sic) buildings reflect this priority.

Crystal Cathedral. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Sport arenas aren’t unlike churches. It’s an easy leap, and one often made: sports stars are often cast as gods, and their battles recounted as if angels and demons were fighting. The stakes of their contests are rendered in terms of good vs. evil, and the stakeholders as us vs. them. These sports teams, like divine factions, fight proxy wars on our behalf. They are our superheroes (and we live in an age busy with imaginary superheroes). In that light, a football stadium could be but an extreme stage for social theater, an arena of the imagination appropriately, eccentrically designed for ultimately mythical contests.

If you really want to show the world how powerful your hometown superheroes are, you should put them in an intimidating and impressive building. With Minnesota’s Vikings, there is a handy, pre-existing mythological subtext built in. As no corporation has yet stepped up, I submit the new stadium should obviously be called “Valhalla”. Every game could begin with Valkyries descending from what will be the world’s largest transparent roof to help determine the contest’s outcome, each bout a part of Ragnarök, the epic battle of the Norse Gods. (“Ride of the Valkyries” would be ideally suited for play over the P.A. system during the warrior goddesses’ descent, but since that particular Norse motif was already appropriated by a homicidal despot who understood the power of impressive public architecture on his people, anything by Wagner is probably now off the table.) Remarkably, a locally-owned company is part of the stadium’s construction, a company whose name is THOR.

Of course, that’s not how football really works. Such ceremonial elements would likely detract from the main event: a violent, physical course of action going on below the watching crowds, the outcomes of which are far from imaginary. There have been plenty of recent reminders that athletes are not superheroes but prone to pain and suffering and moral conflict like the rest of us mere mortals. And that fact has undoubtedly put everyone involved with the new billion-dollar stadium in a bit of a bind, just as predatory priests have put the Catholic church in a bind. Given those human realities, maybe the new football stadium should have been a simpler affair than the weird building I’ve seen rising on the Minneapolis horizon. Maybe it should have been designed as a practical space, unembellished — a place so unremarkable we might forget that we are watching a blood sport. Perhaps what the game needs is a giant, institutional building to provide an illusion of civility and normalcy sufficient to obscure the fact that we, as fans, gather there to watch players, men drawn from groups we otherwise systemically discriminate against, sacrifice their health and longevity for our entertainment.

Vikings stadium construction site. Photo by the author.

The construction crew of the new Vikings’ stadium is beginning to complete the center beam, and with this work the mystery of the early structure is largely dissipating. It turns out this is not a weird building, after all. It’s just another giant sports complex with the slight sheen of eccentricity. All things considered, maybe that’s all such a building can risk. The stadium’s facade needs to be impressive, but only in the late capitalist sense: a monumental shrine to what money can do, but one that doesn’t invite discussion as to what else money might be used for. Its design needs to be loud enough drown out doubt, loud enough to silence dissent (as well as a bunch of migratory birds) so we can cheer another game day, celebrating the chance to transfer our hopes and fears onto the larger-than-life battle of our imaginary superheroes, but without the sort of surprises or curiosities that might pull us out of that comfortable daydream. Such a building as this will be reassures us that, of course, God is on our side.

Jay Orff is a writer living in Minneapolis. His writing has appeared in Rain Taxi, Reed and Harper’s.