Dancing to the Singularity

UK-based Random Dance is known for interdisciplinary forays into "embodied cognition," movement investigations into how the evolving interplay of mind, body and technology are changing the boundaries of what it means to be human.

WHAT WILL HAPPEN TO THE DANCING BODY, or the notion of “embodied cognition,” after the singularity? That is, after that time in our near future (the originator of the concept, Vernor Vinge, puts the date at around 2030), when—given a variety of scenarios—human consciousness merges with the technological intelligences we’ve created. The work of British choreographer Wayne McGregor, founder of Random Dance, always incites this question, for me, for several reasons.

The first time Random Dance performed in Minneapolis, Entity at Northrop in 2009, we witnessed a new species of dancer. McGregor—who creates his work based on collaborative research with, among others, psychologists, neuroscientists, and software engineers—had set out to create an “autonomous choreographic agent—an ‘Entity’—that can think—and propose moves—for itself,” a program note stated. And indeed that’s what he did. The dancers were physically sentient creatures with an elastic corporeality based in classical ballet technique but taken to physical and kinetic extremes, every move extracted from their bodies with fluid, crystalline precision.

Because I wrote my master’s thesis on the hyper-virtuosic dancing body, and the technological innovations — from pointe toes to the coding of the “disciplined body” (yep, Foucault) to camera techniques like “bullet time” (yep, The Matrix) — that have created it, McGregor’s work is catnip to me. It’s also an irresistible invitation to geek out. His dancers—with their seemingly super-human strength, hyperextended limbs, unerring speed, and apparently boneless manifestations of his choreography—are, in fact, an exhilarating new dance species even if, in the end, they are in fact human.

McGregor is, obviously, concerned with the relationship between mind and body, the intellectual and the physical self, and those interests are evident throughout his work. His research specifically focuses on “the nature of dance-making and the 21st Century body, particularly its cognitive and biological/technological aspects,” according to the website. He calls these investigations R-Research (Random Research). He’s dubbed his choreographic approach “embodied cognition” or “physical thinking.” In this TED Talk, he enacts “three approaches to physical thinking” with two of his dancers. Watch it and be wowed.

RECENTLY, NORTHROP BROUGHT BACK RANDOM DANCE to perform the 2010 work FAR. “FAR” is an acronym for “Flesh in the Age of Reason: The Modern Foundations of Body and Soul”, a book by the medical historian Roy Porter about changing concepts of the Cartesian body-mind split. Reviewing in The Guardian, Lisa Jardine writes of the book:

Painting on a huge canvas, yet with brushstrokes that are meticulous in their brightly pigmented detail, Porter gives us a vivid picture of how modern accounts of the paradoxical relationship between bodily organs and informing sensibility developed, tracing lucidly the transformation of the pre-modern rational soul into a peculiarly modern subjectivity and sense of self.

She also observes:

Porter makes substantial—quite literally—the debates that have traditionally been conducted around arcane intellectual separations of body and mind. His thinkers [e.g., Byron, David Hume, Samuel Johnson] are perpetually uneasy with their own mortal frames, practically willing themselves to believe that mind will endure, once the acutely inconvenient, painful, unwieldy, suppurating body falls away. By the end of the 18th century, Porter argues, the mind-body question is less about the immortal soul than about the possibility of diverting attention from the inconvenience of flesh—of disembodying the voice of reason.

Dance, of course, is all about the flesh. Which is why FAR—an intellectual work, and a work of the mind based on McGregor’s ideas about, concepts of and studies into embodied cognition; and yet a work in which the body, wearing McGregor’s choreography to manifest his intellectual ideas—is so fascinating. And extreme. Here was McGregor’s concept of the 21st century body, moving within an exhilarating electronic soundscape of plaintive, melodic, digital noise by Ben Frost; inside an ambient lighting design by Lucy Carter, and in front of a set—a magnificent computerized pin board of 32,000 LED lights—by rAndom International.

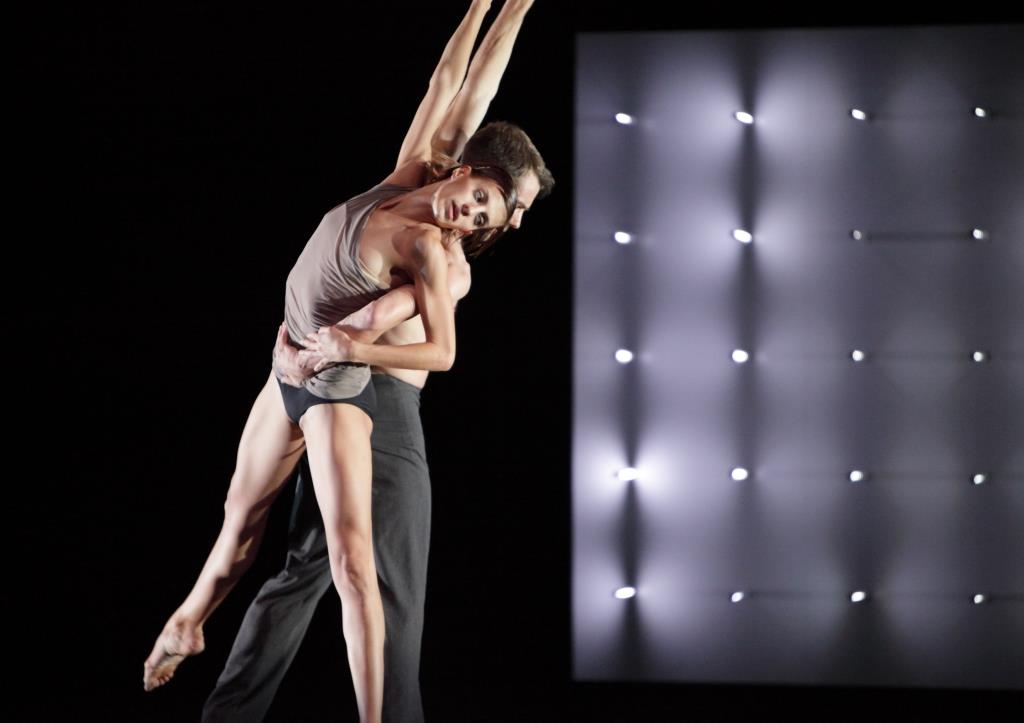

Witnessing the work was a full mind/body experience, as Frost’s soundscapes reverberated in my chest while the jaw-dropping choreography opened out across the stage in quicksilver skeins. FAR seems to be split into seven sections, each one demarcated by a shift in the lighting as well as the color, shapes, and movement of the pin board. The opening section was a stunning example of classicism, from the hand-held torches, to the recording of Cecilia Bartoli’s “Sposa son Desprezzata” by Giacomelli, to the operatic pas de deux of hyperextended arabesques and statuesquely morphing poses.

Shift: What is happening in the second section — physically, intellectually, spatially, aurally? Frost’s score comes into play, as does the pin board. With the shift to the electronic—aurally and visually—have we moved from the past into the present, or even the future?

Shift: In the third section, lit in black and white, lights ebb across the board like waves across a lake’s surface. The dancers’ hands flick like flames. Rippling torso isolations, and a gravity-defying rise from the floor elicit gasps from the audience. Frost’s score includes the sound of, seemingly, dinosaurs grawking. How can the choreography seem both primeval and beyond human at the same time?

Shift: The light is at once red hot and amber. Numbers appear on the light board. Is it a code? An algorithm? What are the bodies articulating about McGregor’s intellectual trail at this point?

Shift: White light, fog, white squares on the floor, and a mesmerizing transformation of what seemed inhuman, or dehumanizing, to a sense of abstraction infused with connection.

Shift: Frost’s score sounds like ice floes shifting, or tanker ships groaning at dock, industrial horns sounding, animals rumbling. Pairs of dancers appear almost languorous—the choreographic vocabulary, their first language, performed with such calm detachment—as they slouch into their hips, hook their legs, lift, touch, grab, pull, pulse, undulate, open and close, or intertwine their limbs in a tumble.

Shift: In the last section, the dancers seem to be breaking free of something more than each other’s limbs, more than the square created by an arm. A man and a woman are left, as the light board flickers like an array of torches. The pair are involved in an altercation, moving within the arcs, angles and lines of each other’s choreography, and with a distinctive return to classicism? Or is it post-modern, post-human classicism? Then, each is alone.

The program included this quote, from Porter’s Flesh in the Age of Reason:

In flesh and blood lay the self and its articulations. With its own elaborate sign language of gesture and feeling, the body was the inseparable dancing partner of the mind or soul; now in step, now a tangle of limbs and intentions, mixed emotions. Organism and consciousness, soma and psyche, heart and head, the outer and the inner—all merged, and all needed to be minutely observed if the human enigma were ever to be appreciated.

If FAR exemplifies McGregor’s ideas about the 21st-century body, what kind of body is it? And what does that body tell us about ourselves? Perhaps he’s suggesting that corporeal intelligence may be our best, or even last defense as the singularity nears.

__________________________________________________

Noted performance information:

Wayne McGregor and Random Dance performed January 14 at the Orpheum Theatre in Minneapolis as part of the Northrop Dance season.

__________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre is a freelance arts journalist and editor of The Line, an online magazine about the creative economy of the Twin Cities.