The New Alphabet of Shapes

On the rise of glitchy, crackly forms shaped by technology of the future and nostalgia for the past

We are organizing a new alphabet of shapes. Spiky, but also sometimes soft, you have seen these distinctly symbolic shapes emblazoned on paintings, stuck like decals, in three dimensions on pedestals, and inked onto skin. Some tend toward looking like a fungus, a virus, an insect, or a seed. Others feel like a sanitized call to the 90s trend of “tribal” tattoos, or the lettering on a metal album. The soft, blocky millennial shapes have fallen, and our visual language has become overgrown by a spinier, faded, neon, glitchy, altered series of crackly forms.

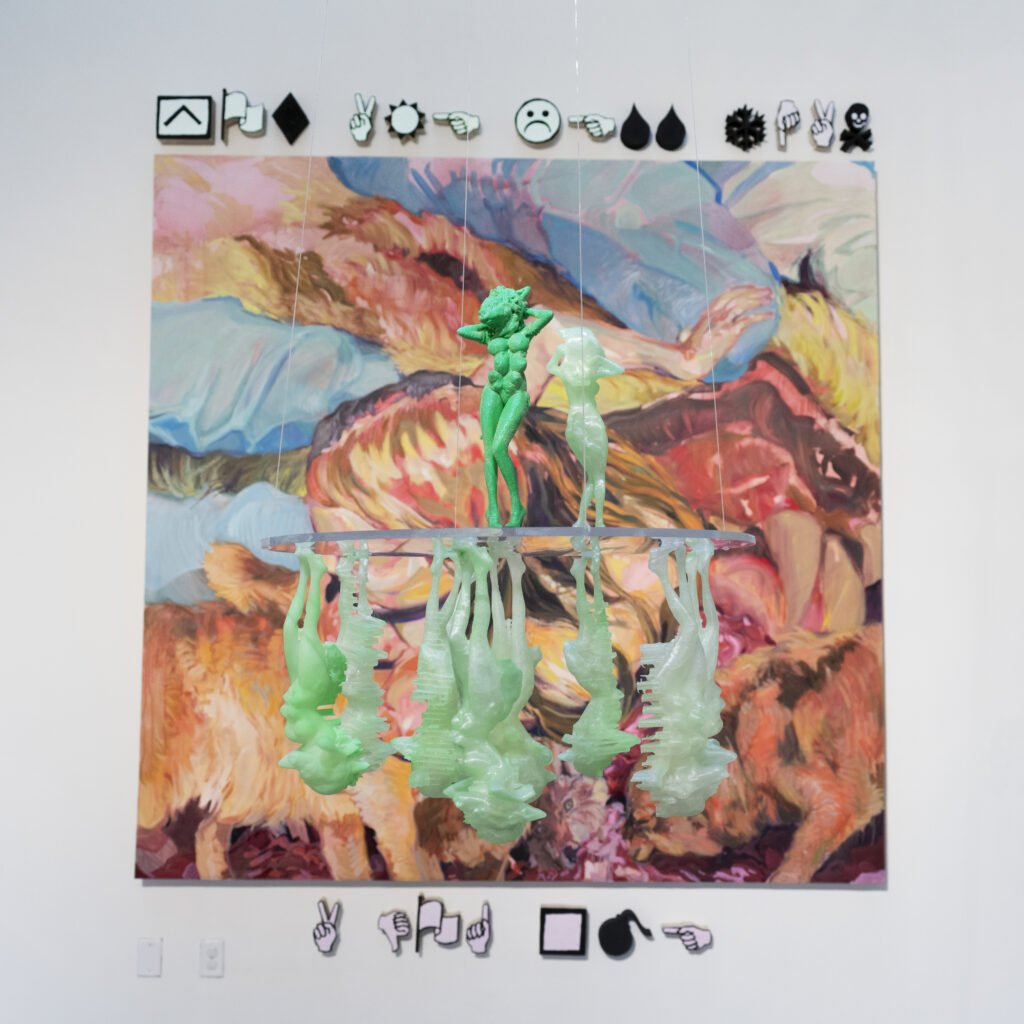

These shapes cycle across place and screen, as ideas echo through the digital and spatial Twin Cities. I comb the wool of my algorithms to find these seeds that I see so often: Hannah Lee Hall’s dimensional pulp works, Sage Phillips’s distorted wolf girl, a ceramic spiderweb at Night Club, Santiago Licata’s exquisite drawings, handpoked Gen Z tattoo artists working in cyber sigilism, @tera_drop‘s delicate and violent graffiti, Christopher Corey Allen’s plasterwork sculptures at HAIR + NAILS, countless other works in group shows at Night Club and Dreamsong. What are the origins, products, and implications of this new alphabet of shapes present in contemporary painting, sculpture, and tattoo? How do they connect with other distortions of the image? Socially, what do these new shapes represent, and what, if anything, do the symbols spell?

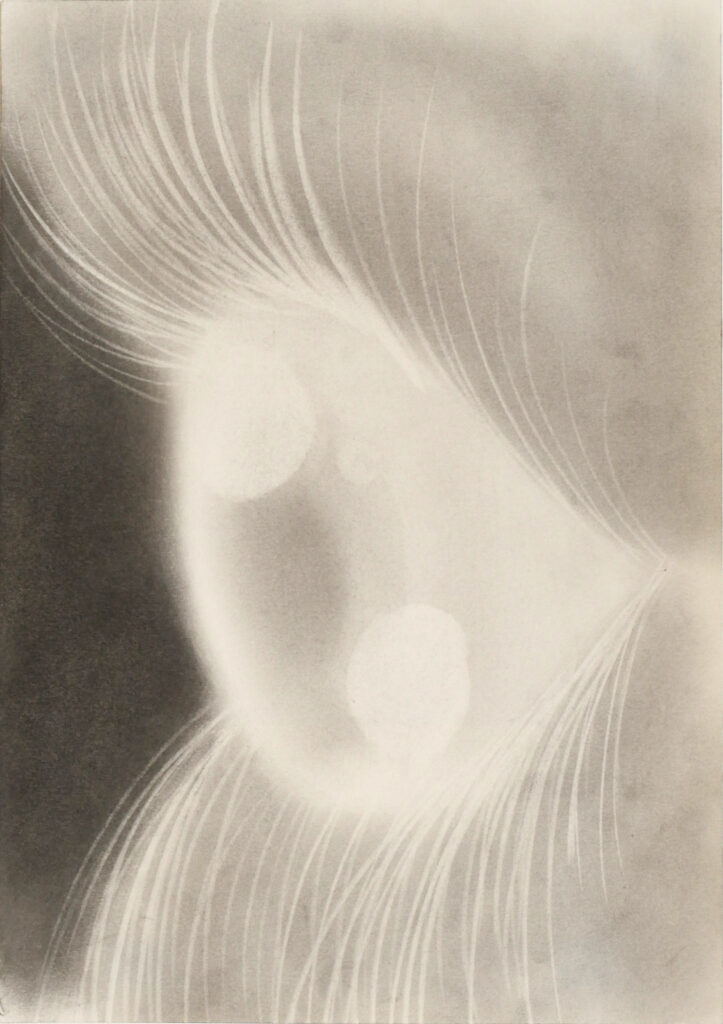

Glitch isolates something like style.1 It makes visible or audible what was previously invisible or inaudible through the process of mediation. This is one of its core spectral qualities; like a ghost, it straddles the line between perceptibility and imperceptibility. Glitch can never fully show the technology that facilitates it, but it does challenge the tendency of digital technologies to recede from view. It records the intra-musculature of machines in mistakes that expose the mechanism. This illusion-breaking stands out against the smooth imagery of AI. AI seeks always to fill in, to make round and robust, to give a lifelike rhythm to its representations. It does this through mimesis and amplification, cheap and pornographic tendencies—which is a problem, since AI “defaults to the worst stereotypes that already exist on the internet.”2

In Glitch Feminism, Legacy Russell draws from Afrofuturism and feminist new materialism to examine the revolutionary potential in exposing these fault lines in the system, tracing their echoes through our own passage in and out of online life.3 Images pass through the barrier as well, permeated with marks of their journey. Some amount of glitch is an inevitability in an image’s future, as it enters the archive, as it is documented or posted or shared. We constantly plunge our fingers and our gazes through the barrier, picking up unknown alterations to our own images, our inner constitutions. We hate the internet, we love the internet; we need and revile it.

I see a tweet about how we don’t dream about our phones, so I try. I see my phone now in my dreams. The phone in my dreams is a glitch: it exposes that there is a mechanism delivering all this constant, flowing imagery. Sometimes I dream about artworks and artists whose work I see online. I have a dream of an imagined Julia Garcia painting. A figure in earth tones stands in the left third of the frame, blurred. The background is detailed, some thin laser-cut sheet metal with small square perforations. It looks a little like an abstracted pattern of the lights of skyscrapers, little golden glowing squares in a silver grid. A dream brings the glitch to an artist’s work seen through a screen.

I absorbed this through viewing HAIR + NAILS’s recent show CHIMERA through my phone. In the exhibit, featuring works by Julia Garcia, Christina Ballantyne, Rachel Collier, and Emma Beatrez, every figure is subject to a blur, if not a dream. Screens tell us that images give way. Swiping and scrolling and navigating, images give way to new images. We participate in the softening of the image’s boundaries, driven toward or away from rotundity, caught in the glitch, technology in a mechanics of desire. Desire and revulsion operate by the principles of their own physics: soaking in, pooling, beading up. Are we softening our images as if in recognition of this truth, that images give way? Is it true because we experience it, or is it even more true because we made the machine make images make way? Is that what images do?

One action of this mechanics of desire is turning away from the image altogether. To turn away from the image, you add a symbol, then you remove the image, ending up with strange, barbed shapes. Stylistically, they run the gamut from cottage core, to goblins, to microscope slide, to tribal tattoo. Their new nomenclature is cyber sigilism, leaning on language to distinguish the new style from its origins. I am puzzled that these appropriative tattoo images are reentering the lexicon. Is it a passive white exhaustion with antiracism, a desire to be transgressive? Nostalgia for a more permissive time when the world was two degrees cooler? Nostalgia takes on new dimensions in times of struggle. Looking ahead or behind can be a revolutionary tool, but does not always consider the cultural context of previous eras, glossing over racism and systemic oppression. Using the tool of memory does not excuse racism. Maybe it is a typical retro maneuver: from the racism that is literally coded into AI, back to a racism that is thought to be better understood.

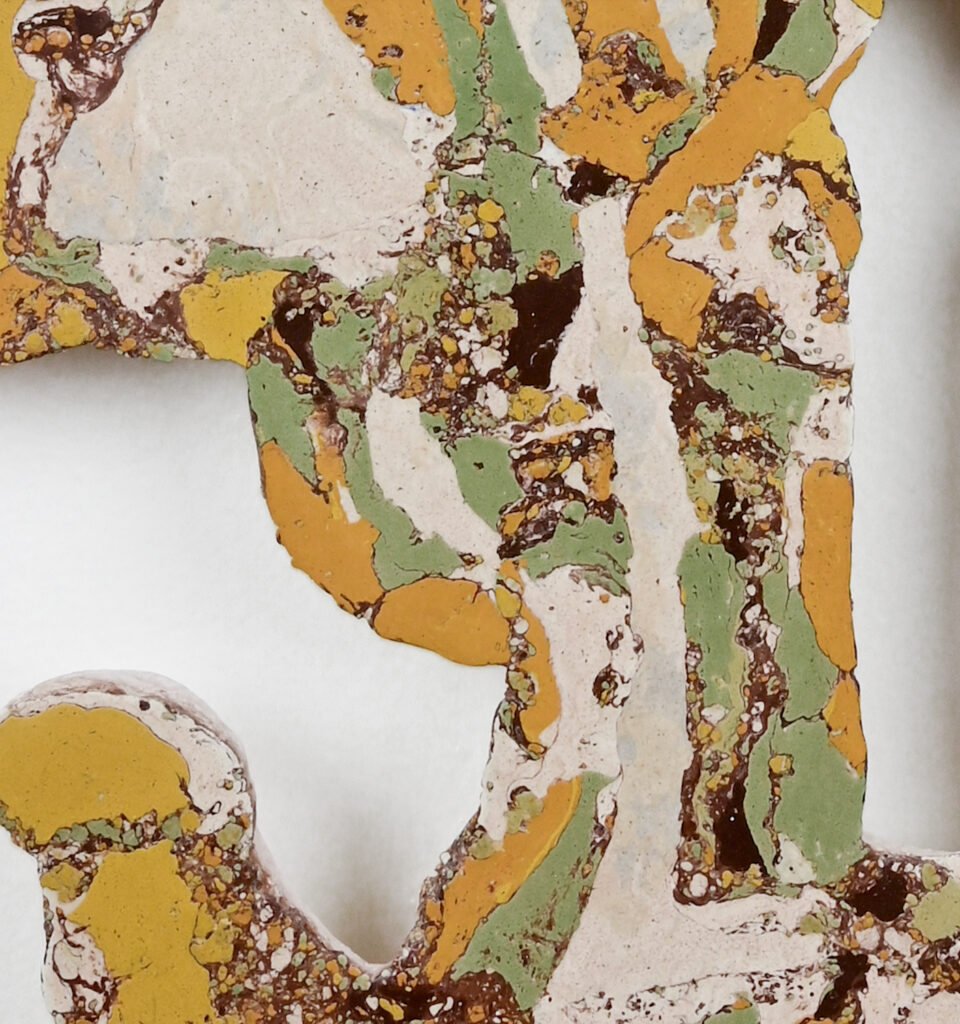

These little shapes float as cyphers in the sea of representational imagery. In their simplicity, they are incorruptible, they cannot be ripped off by the machine. Their looking back is a dual gaze: it’s both a glance in the rearview mirror to the recent past of the 1990s and a look underground into deeper pasts. Christopher Corey Allen’s plaster works in From the bull, the bee, as exhibited at HAIR + NAILS, a series of spiny, wall-hanging sculptures derived from imagery of cell division and 3D renderings, straddle centuries. Ancient cells are brought to image with current technology and hewn in 17th-century architectural plasterwork. The process produces a rich range of colors, and a texture which has both a velvety sheen and the immovable stability of a marble floor, despite their brittle dimensions. This body of work looks to spontaneous evolution, where life forms can arise from dust. In content and execution, the ancient and primordial are interlacing fingers with the machine. We see the machine as a moderating force; we see the eye and the hand too.

Christopher Corey Allen, Time Is The Thing A Body Moves Through, 2023. Courtesy HAIR + NAILS.

Christopher Corey Allen, Time Is The Thing A Body Moves Through, 2023. Courtesy HAIR + NAILS.

Christopher Corey Allen, La Mosca, 2023. Courtesy HAIR + NAILS.

Christopher Corey Allen, La Mosca, 2023. Courtesy HAIR + NAILS.

If there is anything we should know from stories, it is that magic is not free. That should no longer be a surprise. Whizzing up a hill on an e-bike will save your knees, while wearing out the knees of someone of the global majority working in a distant country extracting poisonous metals with polluting machines. When AI does a magic trick for you, it makes a machine so hot from thinking that it needs a large facility and vats of water to cool down.4 AI’s increasingly convincing textures seem to shred our last scrap of trust in the image, the last frontier of realistic illusion—and like every frontier, it’s wrought through colonialism; it sears through the tender meat of our remaining biomes. The image is fleeting art in order to keep something safe, to protect something of this illusion. Tracing this new alphabet of shapes, the throughline is the image fleeing itself.

When everything could be fake, how could anything be interesting? These spiky shapes are sticking with me. We could also see them as a burr: something discarded by a plant in order to deliver something into the future. We affix these spiny forms to ourselves and our algorithms and our archives, bearing their futures from our past. These shapes are stowaways, stuck to the side of perishable aesthetics. They ride on into the future, potent germs iterating and reiterating until the day when the machines and their products begin to mulch.