Brooks Turner: History Is Fabrication

A conversation with the 2021/22 MCAD–Jerome Fellow on his ongoing research project exposing fascism in Minnesota, the urgency of the archive, and methodologies of resistance

Yuanrong LiYou see art as a tool for engaging the structure of history, for exposing and deconstructing prevailing ideologies enshrined by textbooks, libraries, archives, and museums. How do these ideas manifest themselves through your recent projects?

Brooks TurnerThe structure of an archive is ontologically linked to imperialism and surreptitiously enforces a hierarchy of knowledge. Despite this disreputability, an archive can be useful, but it must be interrogated as complicit in state violence. My current work traces two narratives that occupy interstices in the historical record. Both stories are shaped by archival documents as well as oral accounts spanning time and place.

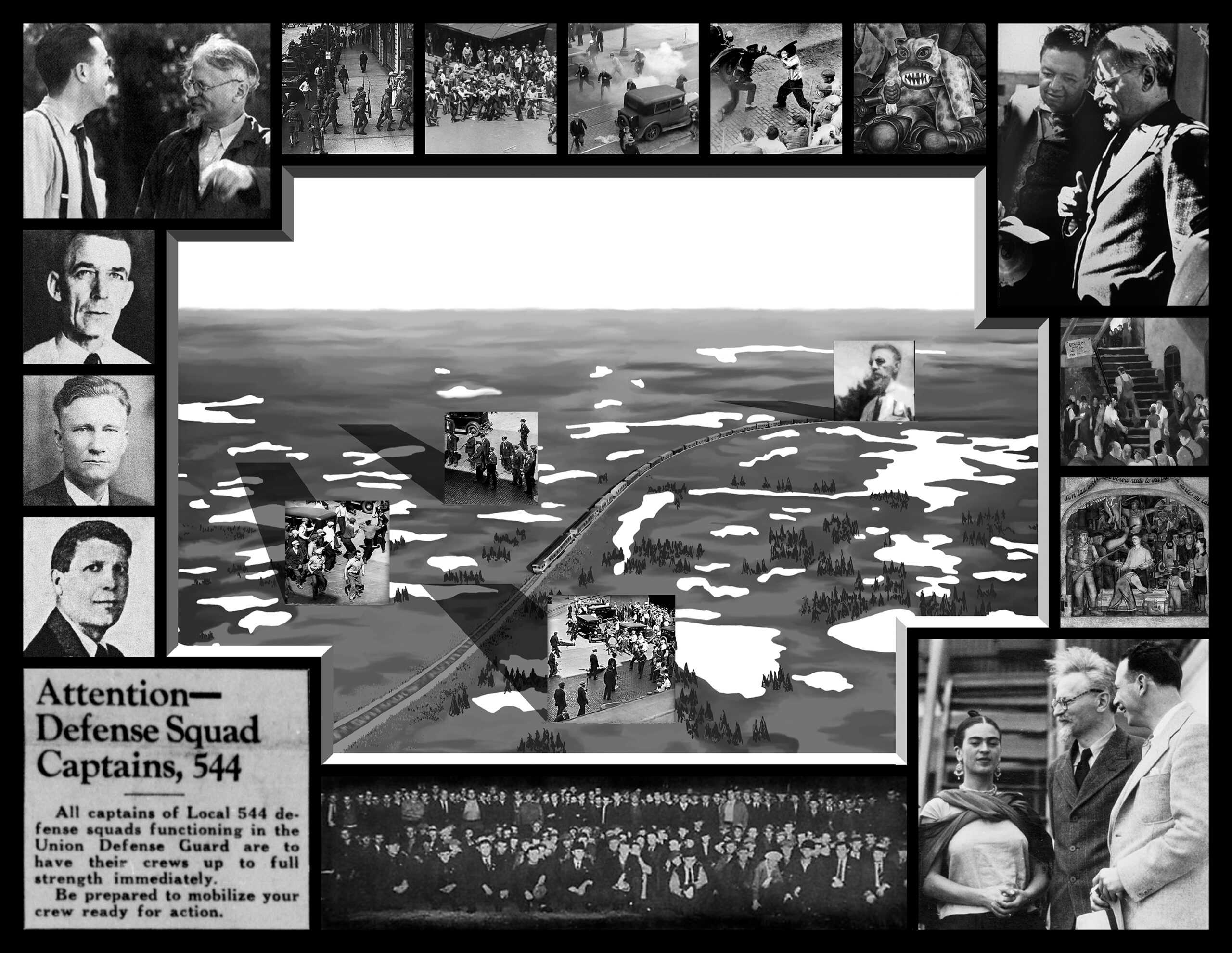

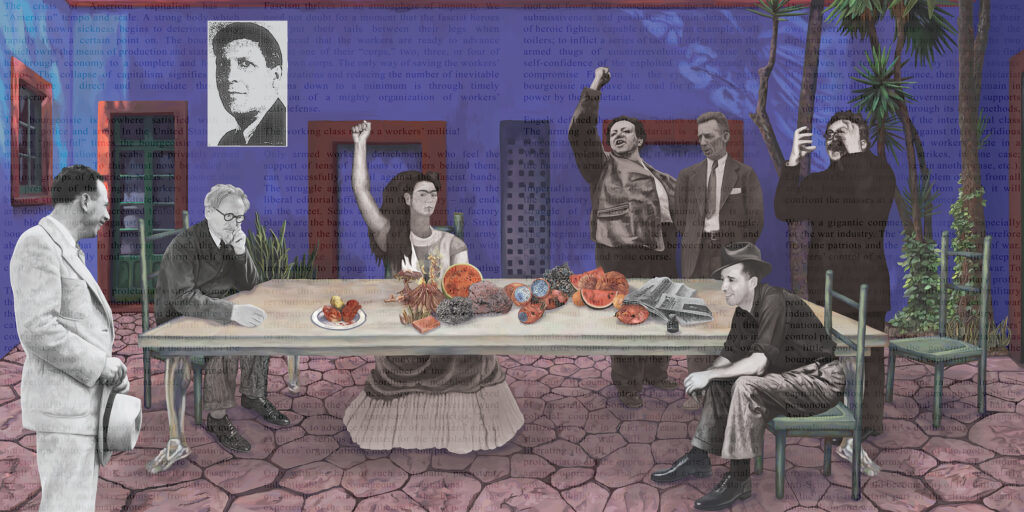

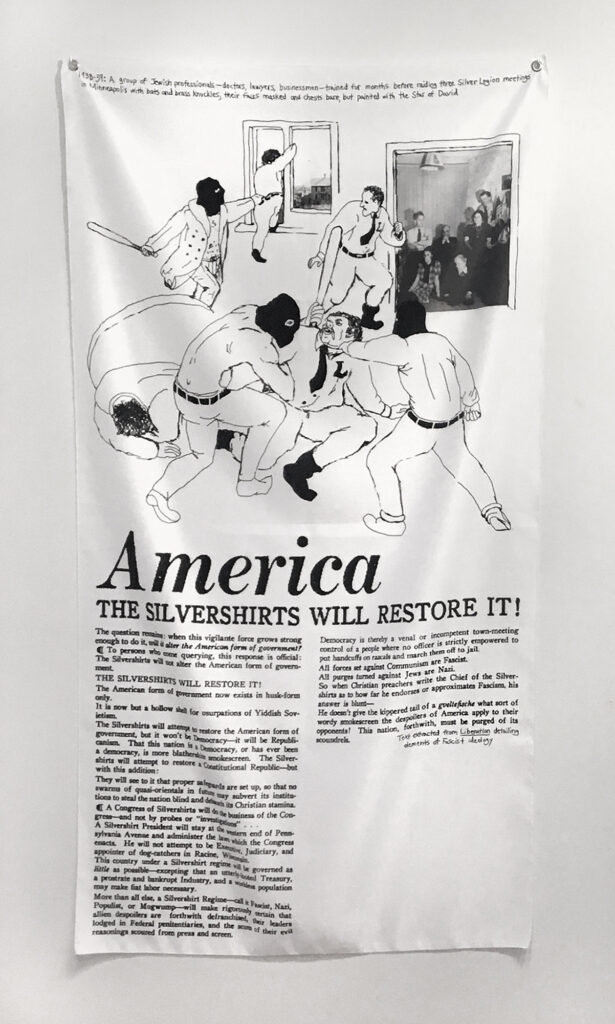

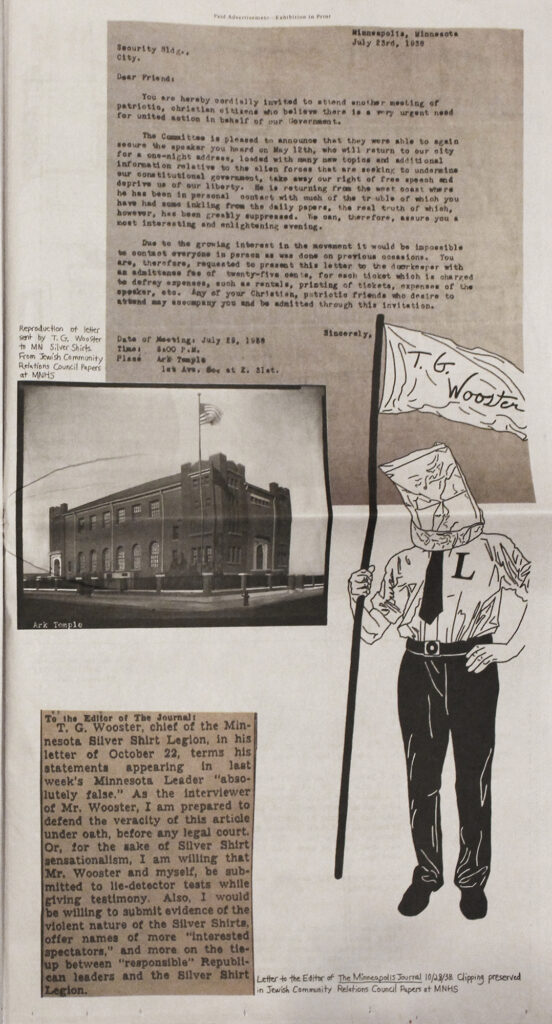

The first: in the summer of 1938, Minneapolis union organizers traveled to Mexico to work with Leon Trotsky. One topic of their months-long conference was the activities of the Silver Legion of America, a pro-Nazi organization active in Minnesota. Trotsky advised organizing a Union Defense Guard, and upon returning to Minnesota, these organizers formed such a guard, electing Ray Rainbolt, a Dakota man, to lead it. Only a few months later, the guard was deployed to confront a Silver Legion assembly, successfully driving the fascists from Minneapolis permanently. But my interest lingers on that summer in Mexico. At the time, Trotsky was living with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. I’ve located photographs that show these artists with the Minnesota union organizers but no specific reference to their interaction. I can’t help but imagine how these artists might have had an impact on the union organizers, how their aesthetics might have shaped resistance to fascism in Minnesota.

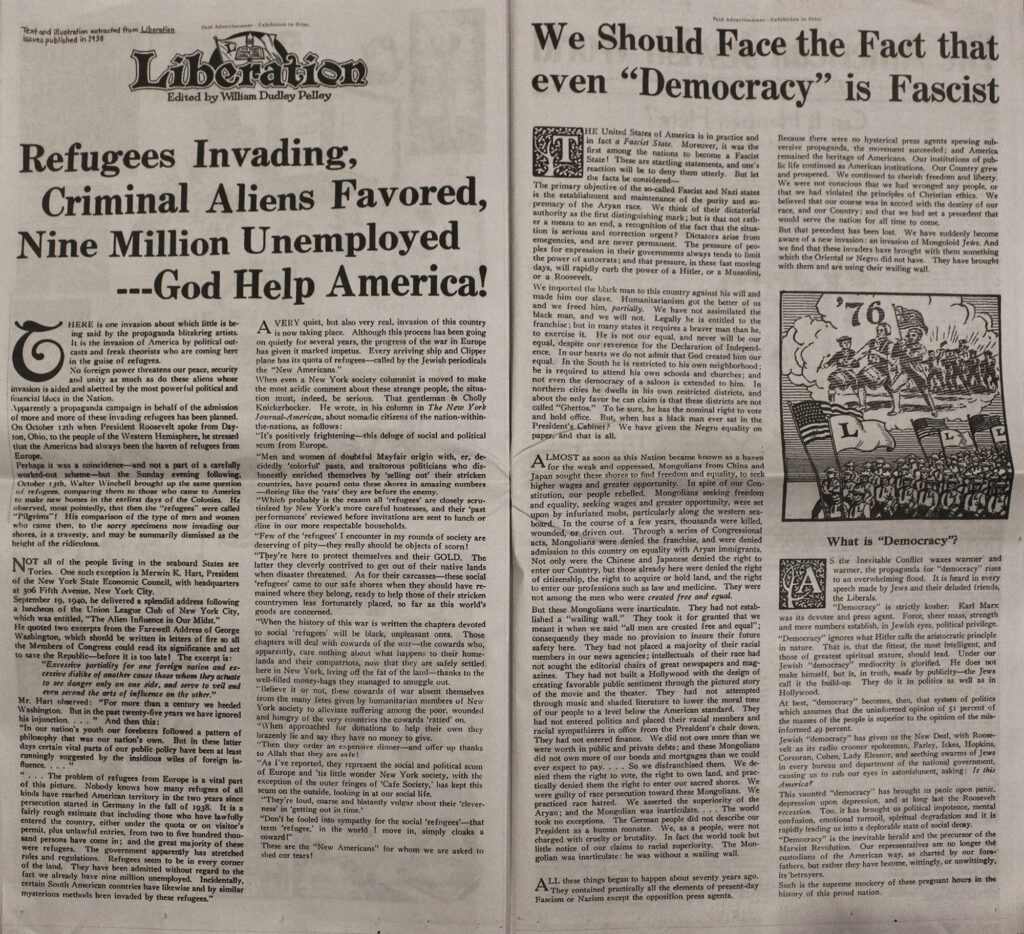

The second narrative was first relayed to me over email: the writer described a self-sufficient American Nazi camp that operated throughout the 1930s in Hackensack, MN, complete with bunkers, printing press, and cement pads for helicopters or even mounted guns should the war come to the US. In tracing this history, I found little direct evidence to substantiate this account, but numerous coincidences that mirrored the activities of the Silver Legion across America and a direct connection between the camp and Nazi Germany.

YLWhat sparked your interest in exploring fascism in the U.S.? I’m curious how your research has affected you personally?

BT Fascism is a 20th-century adaptation of the ideologies that informed centuries of European imperialism and settler colonialism, and so my interest in fascism extends from a longtime examination of these violent systems more generally. Frantz Fanon and Édouard Glissant had a profound impact on me in college, shaping my academic career and broader interest in phenomenology, which then led to Martin Heidegger. It was through Heidegger that I began an aesthetic analysis of fascism, but it was curator Boris Oicherman who encouraged me to extend this investigation into Minnesota history.

I grew up in Minneapolis, but had been oblivious to the scope of fascist histories here. I was startled by my first visit to the archives of the Minnesota Historical Society, a response that reflects my racial and economic privilege; even though I spent years studying European colonialism, slavery, and imperialism, analyzing the complicity of the U.S. through the writing of Fanon, Glissant, and other postcolonialists, I had still managed to see Minnesota as separate. It felt critical that I probe these histories in order to understand my own complicity in the violent whiteness of my home state, as well as to better prepare myself to recognize it in the present.

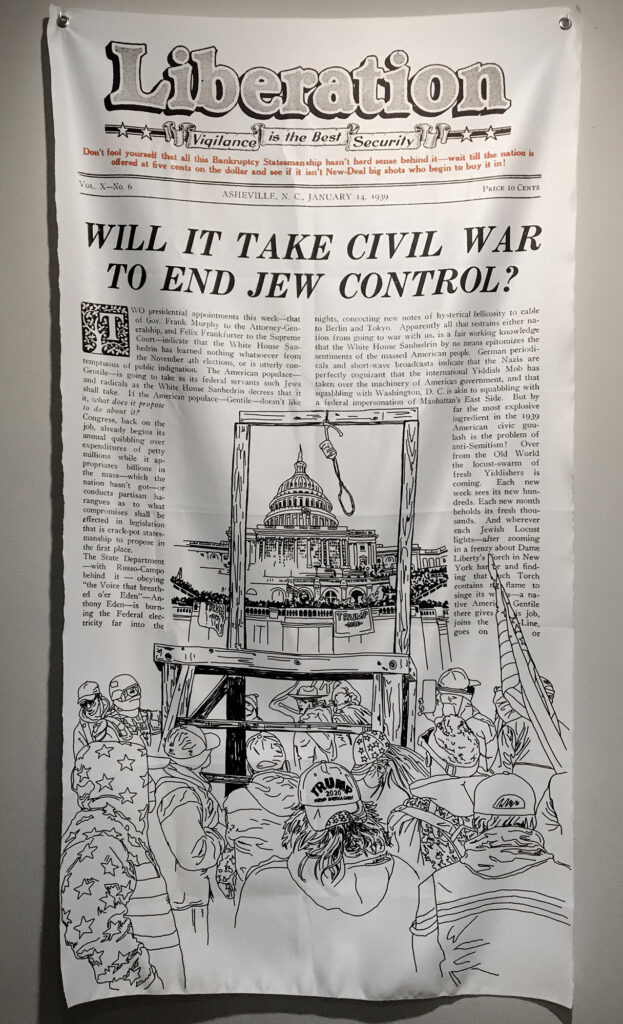

We are all affected personally by fascism in this contemporary moment. Trumpism is fascism; the U.S. right continues to transform our sociopolitical landscape away from the ideals of democracy. But even more critically, moderate bothsidesism is a process by which fascists gain power: the first Nazi coup attempt failed, and the lenient sentences those insurrectionists received only facilitated their future success—not unlike the leniency currently offered those complicit in the January 6 insurrection. This shapes the urgency I feel in pursuing these avenues of research, and has shifted my focus from exposing histories of fascism towards offering strategies of resistance.

YLIn what ways does your work present the complex relationship between truth, reality, fabrication, and feeling?

BTWhen Legends and Myths of Ancient Minnesota went out with the Sunday Star Tribune back in October of 2020, I received a wide array of responses. A woman left a message at the Weisman demanding to know why taxpayer money was used to pay for this “trash.” I was told by a historian that they didn’t consider an oral history I referenced to be “real” history, despite it being published by MPR; another historian claimed my work was unethical because I had identified a connection between the lead archivist at the Minnesota Historical Society and the fascist Silver Legion of America (a connection which is documented in the archives of the Jewish Community Relations Council.) My aunt sent me screenshots of people on Nextdoor discussing the artwork: one thought it was actual propaganda for an existing Silvershirt Society, another thought it was too political, but most commented that history was repeating itself. Overall, responses from academics, artists, and the general public were positive, but I think these negative responses reveal something deeply true about history. What is at stake in practicing history is not knowledge of the past, but rather the very nature of knowledge itself. In other words, history is an epistemological practice shaped by ideologies about knowledge. History is fabrication: it responds to feelings and biases we hold, and therefore shapes how we experience the present.

Art, or aesthetics more generally, is a process of making judgments. And I think we often mistakenly think about this process as either being subjective or objective when in reality it’s neither—it’s relational. Similarly, truth is neither subjective nor objective, but relational. In order to know history, we also have to know the multifaceted worldviews relational to a given record, institution, narrative, etc… And so, in my practice, I strive to exist within this relationality, in which is entangled truth, reality, fabrication, and feeling.

YlMaterializing ideas into form is a complicated process. Can you describe how you go about deciding what materials and techniques to use?

BTIt really depends on the project, but it usually comes to me as I work through a more general idea. Most of my work starts digitally: collages of scans of historical documents, digital drawings of potential histories, photographs of a person or location, etc. I’m interested in the way that digital images embody the democratic potential of reproducibility, as outlined by Walter Benjamin in “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” There’s a kind of poetic in the pixelation of an image as it is scaled down, then scaled up, a record of its circulation. Recently, I’ve become really interested in tapestries woven by electronic jacquard looms. The machine translates my pixelated images into a sequence of threads, which at a distance becomes a resolved image. And like a digital image, up close the lines of thread collapse into gridded abstraction. Tapestries often depicted scenes from mythology or history, functioning to justify the hierarchies of royalty, the church, and the aristocracy. I’m interested in subverting this history by depicting union organization, while still embracing their social potential as, in the words of Le Corbusier, “nomadic murals.”

YlHow much historical knowledge does your audience need to have to be able to appreciate your work?

BTNone, but I’m really interested in the hypothetical viewer who feels that they needed some historical knowledge in order to appreciate my work. I think having that feeling means this hypothetical viewer actually encountered the epistemological dimension of history, which is rife with holes, with absences, contradiction, paradox, and myth. I want my work to generate from these holes.

YLWhat is your most favorite project that you have made? What about that makes it stand out to you?

BTI don’t know if I have a favorite, but I think Legends and Myths of Ancient Minnesota was the strongest synthesis of my making and thinking to date.

YLHow do you balance the relationship between your own writing and visual art?

BTThe idea of balance implies opposition, two weights set against each other in order to equalize and stabilize. I don’t see my art and writing in this way. All of my activities—art, writing, teaching, being a dad—are continuous, fragments of my embedment in the world. One facet of Glissant’s concept of relation is chaos-monde, a definition of the world as so complex and entangled that it defies any form of systemization. By denying the categorization of different aspects of my activities in the world, I seek to advance relation, if only within myself.

YLHow has winning the MCAD-Jerome fellowship affected and/or changed your work?

BTI feel I am always short on time. This opportunity will allow me to structure my schedule in such a way that I can dedicate myself to my more ambitious projects.

YLIf you could describe your work in one word, what would it be?

BTDiscursive.

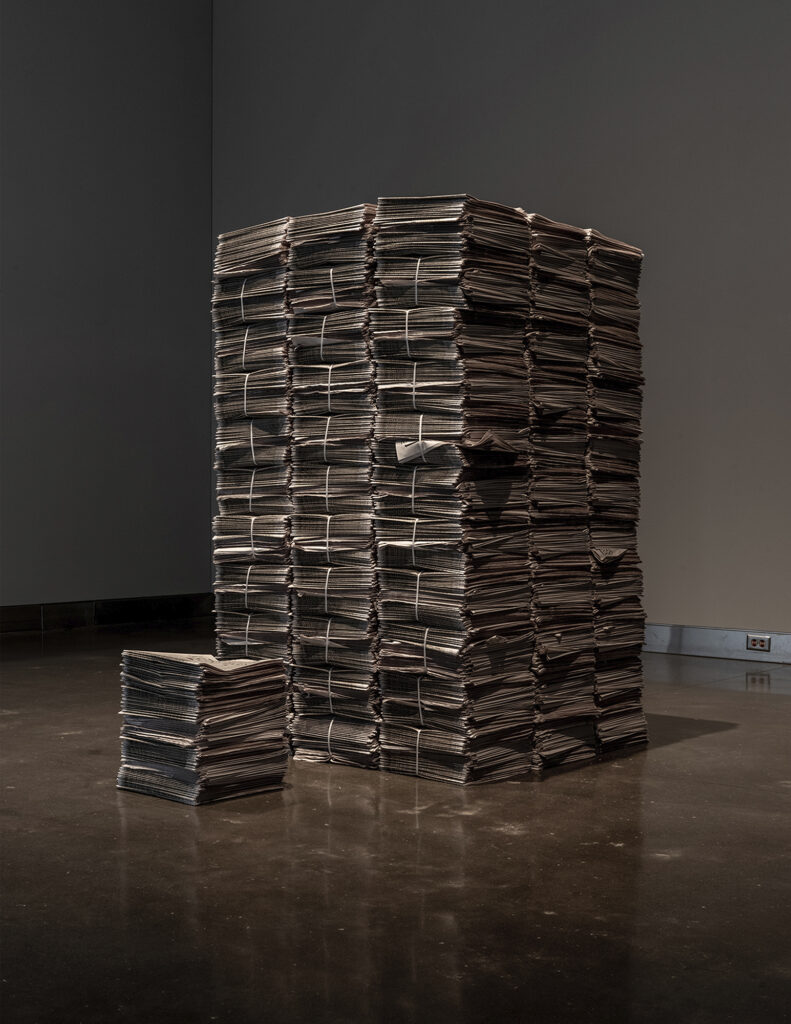

Brooks Turner is an artist, writer, and educator based in Minneapolis. Through diverse methodologies that include archival research, writing, collage, digital drawing, and installation, Turner engages the history of fascism in Minnesota as a synecdoche for understanding and challenging the aesthetics of U.S. history and the imperialist ideologies it enshrines. As an Artist-in-Residence at the Weisman Art Museum, he created a 32-page newspaper-artwork supported by an Artist Initiative Grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board and a Project Support Grant from Rimon: The Minnesota Jewish Arts Council. More than 42,000 copies were printed: 5000 were stacked as a minimalist sculpture at the Weisman, while the remaining were distributed as an insert in the Sunday Star Tribune. His work has also appeared at St. Cloud State University, Soo Visual Art Center, Steve Turner Contemporary, Claremont Graduate University, the Chicago Art Department, and the Zhou B Art Center, among others. He is the author of A Guide to Charles Ray Sleeping Mime, published with Paperleaf Press, as well as numerous essays published by HAIR + NAILS, Art Papers, and Mn Artists. Turner received a BA from Amherst College and a MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles. He is currently Chair of Visual Art at St. Paul Conservatory for Performing Artists and a lecturer at the University of Minnesota and St. Cloud State University.