Bohème Maximale: The Untold Story of One of Minnesota’s Greatest Art Treasures

Andy Sturdevant delves into the tangled history connecting reformist, turn-of-the-century Minnesota governor, John Lind, famed French artist Odilon Redon, Governor Tim Pawlenty, and the unraveling of a 100-year-old secret.

THE FRENCH PAINTER ODILON REDON NEVER VISITED THE STATE OF MINNESOTA in his lifetime. He was born in Bordeaux in 1840 and spent most of his life in Paris, where he died in 1916. During his career, he was responsible for some of the best-known Symbolist paintings of the late 19th and early 20th centuries — The Cyclops, most famously, but dozens of others as well. His work was not exhibited in America until the famed Armory Show of 1913, and, even today, few prominent American museums own much of his major work. Most of those that do are on the East Coast; few are here in the Midwest, although Chicago has several at the Art Institute.

There is one Odilon Redon painting, however, totally unknown to most of the museum-going public-at-large, hanging in St. Paul. It’s a portrait of Governor John Lind, painted in 1902.

You’re, perhaps, thinking the same thing now I was when I began the research for this piece: “Odilon Redon painted a portrait of a Minnesota governor, and it’s hanging in plain view at the State Capitol in St. Paul? Why have I never heard of this before?”

It’s a simple question, but the answer is complex. The painting’s relative obscurity has to do with a whole host of enormously complicated turn-of-the-century political and artistic issues — free silver, prairie populism, Symbolism, European immigration, American exceptionalism, and fin de siècle decadence, among other things — that I’m going to do my best to lay out as clearly as I can.

However, whether you’ve heard of the Lind portrait or not, there’s a good chance you will hear about this painting soon. It’s shaping up to be at the center of one of the most contentious Minnesota arts-related political issues in recent memory. What’s the issue? That question is much more easily answered: Tim Pawlenty.

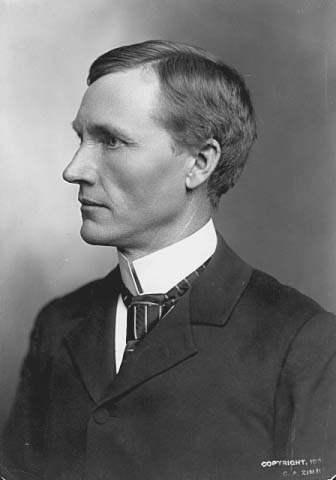

We should begin this story at the beginning, in rural Småland, Sweden. John Lind was born there, in 1854, to a farming family that immigrated to Goodhue County, Minnesota in 1867, two years after the Civil war had ended, and only nine years after Minnesota had been granted statehood. When he was thirteen, young Lind lost his left hand in a farm accident, and consequently retreated inwardly, into solitude and study. Lind eventually went into the field of education, becoming a superintendent; he later earned a law degree from the University of Minnesota, and was elected to Congress, representing Minnesota’s 2nd district. In 1899, he was elected to be the governor of Minnesota as a Democrat, becoming the first in forty years from that party to hold the seat. During his two-year tenure, Lind was one of the most radical governors in Minnesota history. Populist positions such as progressive taxation, civil service reform, direct election of state officials, free coinage of silver, and the eight-hour work day were all causes he consistently fought for during his time in the Governor’s office; these were the very positions that Republican governors of the past — mostly Eastern-born lumber barons and businessmen — had aligned themselves against.

Lind was an intellectual, fluent, not only in Swedish and English, but also, like many educated men of the time, in French. In particular, he was an admirer of the French writer and social critic, Émile Zola, whose naturalist writings on poverty and class struggle struck a chord with the reformist Lind. Zola was widely read in American populist circles, and as a Congressman in 1891, Lind had apparently toyed with the idea of bringing Zola to Burnsville — then the 2nd district’s largest community — to speak at a gathering of populist Democrats and Silver Republicans. The plan, of course, never came to fruition, but there was some correspondence between Lind’s and Zola’s respective offices.

Zola never came to America, but on his recommendation, young French writers traveling abroad were consistently encouraged to visit Minnesota throughout the 1890s and 1900s, to see the populist experiment in action. These writers — mostly journalists, but also poets, novelists and essayists — left our state impressed, not only with the social movements at work here, but also with the landscape itself. So much was written about Minnesota in Paris throughout the 1890s that the body of work practically constitutes a distinct school of French letters, dismissively referred to by some as Les Minnesotains. Counting themselves among this group were naturalist writers in the Zola vein, certainly, but also Symbolists, fascinated with the state’s physical makeup, hallucinatory cold, and dreamlike barrenness. So goes one description of the state’s topography, written by one such writer in 1890: “…over there stretched dry and arid landscapes, calcinated plains, heaving and quaking ground…monstrous flora bloomed on the rocks; everywhere, in among the erratic blocks and glacial mud.” Minnesota, with its unforgiving ruggedness and vast social divides, presented to French writers “not only a model for modern social reform, but also a deeper, more troubled metaphor for the vast, unknowable expanses of the human psyche,” according to one historian.

Among these Symbolist artists and writers whose fascination with the state coincided with Lind’s administration was Odilon Redon. Redon found himself, in fact, in a precarious position over a rift that was forming in French letters among Les Minnesotains. Those more inclined to populism, liberalism, and naturalism viewed the state and its various reform movements as a social metaphor for how a society could transform itself (les Minnesotains sociales); those more inclined to Symbolism, decadence, and pure aesthetics saw the state and its harsh, rugged, featureless landscape as a metaphor for the human experience at large (les Minnesotains symbolistes). Redon, a Symbolist painter whose background also included a stint as a liberal, anti-Imperialist journalist, felt torn between these two approaches. He had friends and admirers in both camps. During the 1899-1900 season, of all the arguments raging in the coffee shops and cabarets of Paris, perhaps none were more heated than the sociale/symboliste split.

______________________________________________________

There is a sad irony in the fact that the portrait of one of Minnesota’s great reformist crusaders was brought into Minnesota in a flurry of palm-greasing. The deception at the heart of this artwork’s history in our state was “a dreadful idea,” wrote one patron behind the decision, “but perhaps the only course of action available to us.”

______________________________________________________

What happened next is one of the great untold stories in Minnesota art. Lind’s administration ended in 1901. As governor, he had been instrumental in focusing the interest of these small groups of influential French artists on Minnesota, on broadening the debate between naturalism and Symbolism, and there was much discussion in Paris at the end of his term about how he might be remembered. Passions continued to run high: “It was a period of unimaginable bitterness, worse in some respects than 1871,” notes art historian Steven F. Eisenmann in the 1992 book, The Temptation of Saint Redon.

Meanwhile, in Minnesota, Lind had made few friends in the urban elite, in spite of some support from the Twin Cities’ burgeoning cultural community. A small cadre of Francophiles, noblesse oblige-crazed heiresses, arts supporters, and wealthy liberals decided, as soon as his administration ended, that they would endeavor to raise the appropriate funds in order to see that Lind received the finest portrait in the state’s relatively brief history — a painting that would stand out from the grim, chiaroscuro-choked oil representations of his predecessors. One of them had the idea to contact Zola’s offices to find an appropriately modern, progressive artist in Paris who might be up to the task. Zola’s secretary referred them to Redon.

Redon, once hearing the offer from the Minnesotans, agreed to make the painting. Primarily, he liked the idea of creating a work that would speak equally to the contending factions of les Minnesotains, which would address both aspects of Paris’s current intellectual fascination with the faraway, almost mythical state. The funds Lind’s benefactors in Minnesota raised were too meager to allow for transatlantic travel, but Redon was provided with numerous photographic sources from which to work. He began the painting immediately, in mid-1902.

Of course, there was one problem. As is often the case with well-meaning, wealthy patrons, no one seemed to have carefully considered the practical and legislative barriers to such an endeavor. The Minnesota legislature, that year, was controlled by conservative Republicans, and when word reached them that the radical governor’s portrait was being painted by a European decadent, the outcry was forceful. “It will not stand,” declared the Republican Speaker of the House. Having already put the money up front, and not wanting to appear provincial in the eyes of the Parisians by canceling the commission partway through, the Lind’s supporters made a crucial decision: they would hide the identity of the portrait’s artist from the legislature, bringing the painting into the country, but concealing its origins with an obvious pseudonym — “Max Bohm,” a pun on the phrase bohème maximale: “maximum Bohemian”; they planned to pass it off as the work of a domestic painter. “A dreadful idea,” wrote one patron behind the decision, “but perhaps the only course of action available to us.” Redon’s painting arrived via rail in late 1903, the bill of goods deliberately falsified, unbeknownst to the artist; crucial journalists and politicians were paid off to remain silent. There is a sad irony in the fact that the portrait of this reformist crusader was brought into Minnesota in a flurry of palm-greasing.

Redon went to his grave never knowing that the painting was displayed under the name “Max Bohm.” In fact, Lind’s portrait is still attributed to this obvious pseudonym in official state records. The listing of the work, according to the Minnesota Historical Society’s records, is “Max Bohm,” as is the physical plaque in the Capitol. Thanks to the deception, the legislature was appeased; Lind was disgruntled at being the subject of such a ridiculous ruse, but he kept quiet on the matter until his death in 1930. “That French painting…” he was rumored to grumble from time to time, in his lilting Swedish accent, “So silly what they’ve done.” The portrait hangs in the Capitol today, obviously the work of a French Symbolist, but even now attributed to “Max Bohm.”

The French mania for les Minnesotains turned out to be short-lived, and died down shortly after Lind left office. As the United States expanded westward, new states captured the imaginations of continental artists: Utah, Oklahoma, Montana. (Many authoritative accounts have already been penned of the cowboy-crazed French artists known as la Montaniens.)

The painting itself is perhaps a minor work in Redon’s career, but it is beautiful nonetheless. Lind stands, facing the West, the “stretched dry and arid landscapes, calcinated plains, heaving and quaking ground” rolling behind him — it all looks fantastical, those “monstrous flora bloomed on the rocks,” and the air charged with Edenic possibility. His hands are behind his back, hiding his missing limb. As an official portrait, it certainly does stand out from its predecessors. It suggests untapped possibility: not only in the social and political realms, but also aesthetic and, perhaps, even spiritual potential. The way the clouds roil overhead, and the way the landscape unfolds excites the imagination in a way that other official gubernatorial portraits hanging nearby do not.

Fast forward to the year 2010. Much of the information in this piece is gleaned from an unpublished 2006 paper on the Lind portrait, written by University of Minnesota art history graduate student, Marisha Ferguson. Though the paper hasn’t yet been published, the true story of the painting’s incredible provenance clearly made its way, somehow, to the Capitol. A 2007 audit of the state’s financial holdings, commissioned by Governor Pawlenty, lists the work quite high on the list, where it is valued at around 1.6 million dollars; it’s a surprisingly high figure for a Redon piece, and quite a bit more valuable than any other work of art currently in the state’s possession. In Pawlenty’s budget for 2010, a small item in the appendix suggests selling the portrait off to private buyers and applying the assets towards the deficit.

As far as I can tell, not a single media outlet has reported this. I was not able to get a comment from anyone in the Governor’s office about the Lind portrait. I wonder if this move to liquidate the artwork’s value reflects more than simply standard, conservative notions of “common sense” or “fiscal responsibility” at work; to me, it feels like a crude form of belated vengeance against an embattled, but genuine reformist, enacted by just the sort of conservative Republican Lind fought in his time, albeit a century later.

It is true that the painting’s provenance is murky, barely believable, and as fantastical as the painted oil landscape itself. It’s quite a tale, to think that French Symbolists sat in outdoor cafés of Paris a hundred years ago, debating the merits of Minnesota; even more, to imagine that one of the greatest of their number was enlisted to create a portrait of that state’s inspiring young governor, only to be betrayed by bigotry, short-sightedness, and misplaced noblesse oblige — first in the early years of the last century, and yet again in the early years of this present century. Outrageous or not, though, this is a story too important to our state’s history to let it end the same, ignoble way twice.

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

About the author: Andy Sturdevant is a writer, curator, and artist living in South Minneapolis.