Animating Sound

Alison Morse profiles composer Tom Hambleton and animator Tom Schroeder, both of whom have become adept at the art of sound design in animation, using the complex interplay of sound and image to create "visual music."

WHEN YOU WATCH ANIMATED FILM, IT MAY BE THAT THE EYE-POPPING VISUALS first grab your attention, but the film’s soundtrack is working on you, too, whether you consciously attend to its influences or not. In fact, some of the best animated films spring precisely from that complex interplay between what is seen and what is heard, relying on a conversation between sound and image to tell the story. The Twin Cities are home to two artists notable for their accomplishment in this arena — one’s an animator, the other a sound designer — both of them have long been fascinated by this dialogue between forms.

About 25 years ago, Tom Hambleton and Tom Schroeder met at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin. There, they each played music and shared a keen interest in filmmaking. After college, both moved to the Twin Cities, where Schroeder began tinkering with animated film and Hambleton focused on music, occasionally helping his filmmaking friends, including Schroeder, with their soundtracks.

Fast forward to 2010. Tom Hambleton has become an internationally sought-after composer, sound designer, and engineer for film and video, who specializes in sound for animation. Tom Schroeder makes award-winning animated films with soundtracks that he designs himself. They share a passion for experimentation, and both are obsessed with finding thoughtful, fresh ways to pair the two media. Separately, they are hard at work this spring on new projects that display a playful approach to sound design for animation.

Since 1990, Tom Schroeder has created animated films that have been screened at dozens of film festivals, including Sundance, Ottawa, Annecy, and Edinburgh. He has received fellowships from the Minnesota State Arts Board, both the McKnight and Bush Foundations, and teaches animation at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.

Schroeder’s approach to animation puts sound on equal footing with visual imagery; like a jazz musician, he collaborates with and improvises from his soundtracks. Improvisation, he says, is “really an extemporaneous piecing together of a predetermined vocabulary, with a few risks and surprises along the way.” Take Bike Race, Schroeder’s newest work-in-progress, for example. The film began, not with the visuals, but with two voice tracks. One, recorded seven years ago by his wife, Hilde De Roover, is a “playful mock-documentary” of a bike race between Schroeder and his friend Cis, with De Roover in the role of reporter. On the second track, Schroeder and Hilde describe how they fell in love during the course of the race.

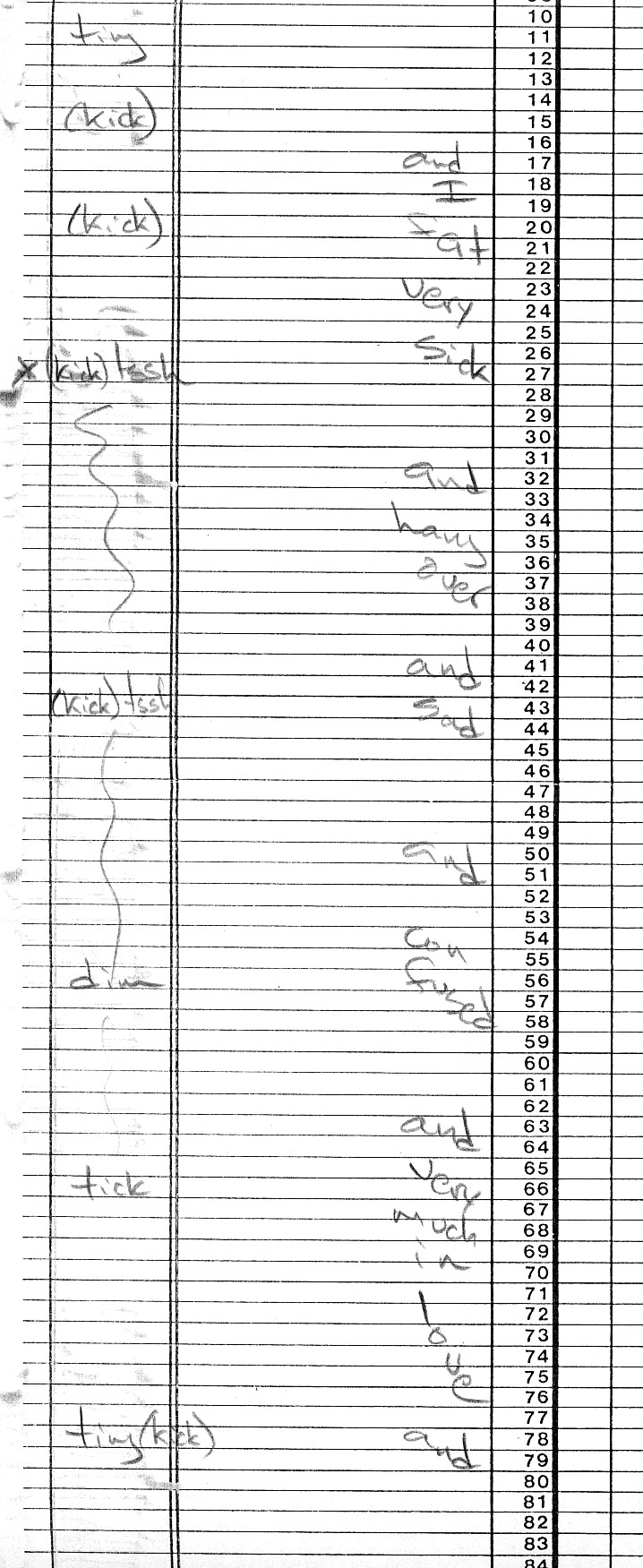

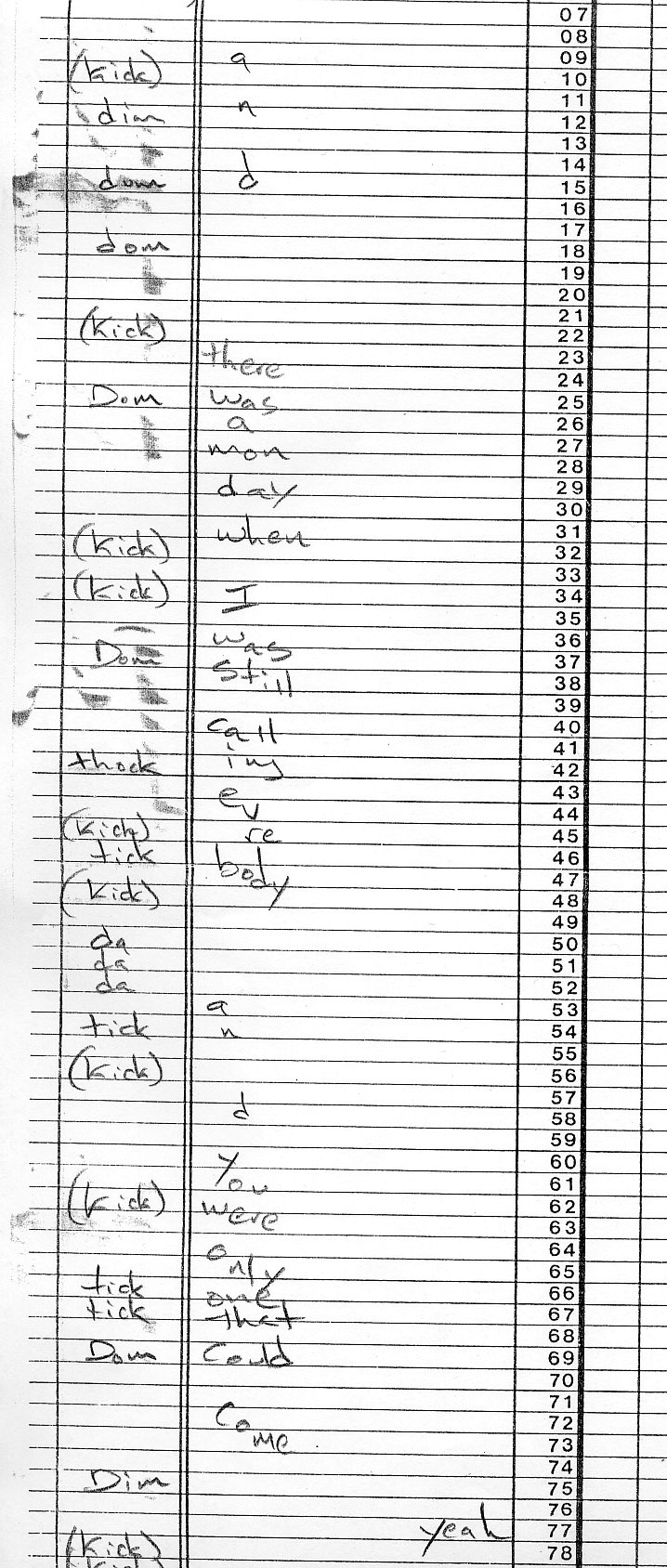

Tom edited two hours of voiceover material into the twelve-minute narrative that he gave to master drummer, Dave King. “So what Dave does is, he’ll listen to the story and come up with ideas.” In fact, after studying the voice track as a whole, King sat down in Schroeder’s basement studio and responded with his drum set — all in one take. The musician listened for beats in the dialogue that he could accent with his drum and for places in the narration where he could play “sound effects” — like a “thock, tic” to suggest clinking glasses. He also listened for moments that he could respond to “metaphorically.” For example, in a pivotal scene where Schroeder has just won a race (and, secretly, Hilde’s heart), he sings the REM song “It’s the End of the World As We Know it.” King’s rhythmic counterpoint to this scene is not a rock beat, but “an apocalyptic falling down sound” that mimics what’s happening in the characters’ psyches at that moment.

Only now is Schroeder drawing his animation, and he’s doing so “straight ahead” (following the soundtrack without planning out a storyboard beforehand) “in the same spirit as King’s playing, only it’ll take me a year and half, not twelve minutes.” To do this, Schroeder had to first “transliterate” every drum thwack and “mm-hmm” onto a dopesheet that shows the duration of each sound in film frames. One second equals twenty-four frames and twelve drawings.

I saw a snippet of the new film on a laptop in Schroeder’s animation studio, a room in the St. Paul home he shares with De Roover. All the elements work together seamlessly, like a great jazz ensemble. Voices and natural sounds (the result of taping the original bike race soundtrack outside) become part of a musical fabric woven together by Dave King’s beguiling drum track, which evokes the noises of everyday life and anchors the rhythms of Tom’s constantly morphing line drawings. Schroeder and King collaborated on another bicycle-themed short several years ago, Bike Ride, which you can see below.

The idea of animator as visual musician is not new. Tom’s influences include Len Lye and Norman McLaren, two mid-twentieth century animators who experimented with “visual music,” and George Griffin, whose 1988 collage animation, Koko, visualized a Charlie Parker score. Another inspiration, he says, is the French live-action director, Jacques Tati, who made quirky, dialogue-free comedies from the ’40s through the ’70s. “He’s almost like a live-action animator,” says Schroeder.

IN SOME WAYS, TOM HAMBLETON’S APPROACH TO SOUND DESIGN couldn’t be more different from Tom Schroeder’s. For one thing, Hambleton is not an animator at all, but the owner and chief sound designer of Undertone Music, Inc., a “full service audio production facility.” Housed in two floors of a building in the warehouse district, Undertone is Hambleton’s state-of-the-art sound recording, editing, and mixing studio. Here, he and his assistants work on commercial and corporate videos, live-action films, and a wide array of animated shorts.

“I look at every job differently,” says Hambleton. He asks “Who is the target audience? Where is the piece destined to play? What are the artistic elements within the piece itself?” and “What are the producer and director looking to achieve?” These may seem like standard questions for any commercial sound designer, but Hambleton is no ordinary sound guy.

When working with Dutch animator Rosto on the sound design for his animated film Jona/Tomberry, Hambleton spent days recording and re-recording water sounds sped up, slowed down, accelerating, and decelerating on an old-fashioned analog tape recorder. Next, he added layers of sound (like wind) for an “organic” feel. When Rosto demanded a singing baby (“not a cartoon baby”), Tom recorded one soprano singing the multi-octave melody and another soprano with a “whistley quality” for the reverb track. The resulting soundtrack is as dense and varied as the film itself, a baroque 3D computer-animated dystopian vision, which won the Canal + Grand Prix at the Cannes International Film Festival.

Hambleton’s latest collaborator is Andrew Chesworth, a brilliant young American animator in love with 1940s Disney cartoons. His film-in-progress, The Brave Locomotive, tells the story of a squashy-stretchy child-like train. To start the piece, Andrew mapped out the film’s timing with an animated storyboard (a Quicktime movie of pencil sketches). Then Hambleton went to work, composing a song to narrate the film, creating music that does triple duty: mimicking the movements of the train, commenting on the emotions of the characters, and setting the mood by changing musical styles. Anyone who has spent her childhood watching re-runs of Bugs Bunny intuitively knows these cartoon soundtrack conventions, as perfected by Warner Brothers’ music director, Carl Stalling. Hambleton calls his style: “Carl Stalling — in my way.”

To create that classic cartoon sound, Hambleton bought a special microphone, based on a 1930s-era Ribbon mic — it weighs 10 pounds and looks just like the microphones in old Hollywood movies; with it, he recorded the Andrews Sisters-esque vocalists, piano, bass, and drums that realized his retro score.

And now, Chesworth is working to animate this recorded performance. When he completes the visuals, Hambleton will, while watching the film, respond with sound effects on hand-made contraptions, the same way the Disney studio used to record sound effects for its cartoons.

This process is much like Tom Schroeder’s “straight ahead” approach to his current animation project. After all these years, both Toms have, in many respects, come full circle, albeit from different directions — they’re both innately collaborative artists, playing with others to create visual music, part of a venerable animation tradition and a brave new dialogue between image and sound that they began together twenty-five years ago.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Alison Morse is a writer, teacher, and former animator. She also runs TalkingImageConnection (TIC), an organization that brings together writers, contemporary visual art, and new audiences. The next TIC reading will be on June 17th, 7 pm at the Tychman Shapiro gallery. For more information, contact yackmor@talkimage.org.