After Symbols and on to Lawlessness

Critic and curator Nathan Young on the "catalytic flag-making" project, "Bleed&Burn," (ongoing now at the Soap Factory) and pushing the momentum of art for social change beyond symbolism and into action in the civic sphere.

The Soap Factory’s Bleed&Burn: Catalytic Flag Making shows a crossroads of activism, where the momentum of art for social change is pinned between symbolic revolts and literal, even legislative, advocacy. This gap is hard to see. Organizers Alexa Horochowski and Crystal Quinn refer to Bleed&Burn as an “exhibition/action” — an unusual description, emphasizing the two deeds, protest in symbol or in action, as both partners and opposites. Like the relationship of squares and rectangles, an action can produce exhibitions, but such shows do not reliably lead to action beyond the gallery.

This exhibition of 14 motionless flags by 13 artists in a gallery space announces each flags’ ceremonial burning, planned individually for yet-to-be-determined times and sites across the Twin Cities. The visual anthology of Bleed&Burn will be published by Beyond Repair, an artist-run bookshop and printing press based in Midtown Global Market. The project’s handout describes the flag-burning as “symbolic speech,” alluding to the landmark US Supreme Court decision in 1989 that decreed flag desecration to be constitutionally protected speech because, as Justice Brennan notes, it is “highly symbolic conduct.” Now, all speech is, in fact, vulnerable to censorship, not because unchecked language risks harming the citizenry, like yelling fire in a crowded auditorium, but because unsurveilled citizens might jeopardize the powers that be. Speech is censored because it leads to action.

The only legal justification for banning free speech in America is the “incitement of imminent lawless action.” In 1919, Russian immigrants who canvassed factory workers to strike in sympathy with their homeland were convicted under the Espionage Act of 1917 for encouraging resistance to the US war machine. Anita Whitney was likewise convicted in 1927 under California’s Syndicalism Act which “prohibited being a member of an organization that advocated unlawful methods as a means of bringing about socialism ‘or effecting any political change.’”1 The US Supreme Court upheld both convictions, determining each incident clearly endangered an American way of life. In the 1989 case, Texas v. Johnson, the court ruled not to abridge freedom of speech in the form of flag desecration because it posed no such threat as found in cases like those from 1919 and 1927. As Justice Brennan figured, flag burning was just highly symbolic conduct. In other words, it was an exhibition of art.

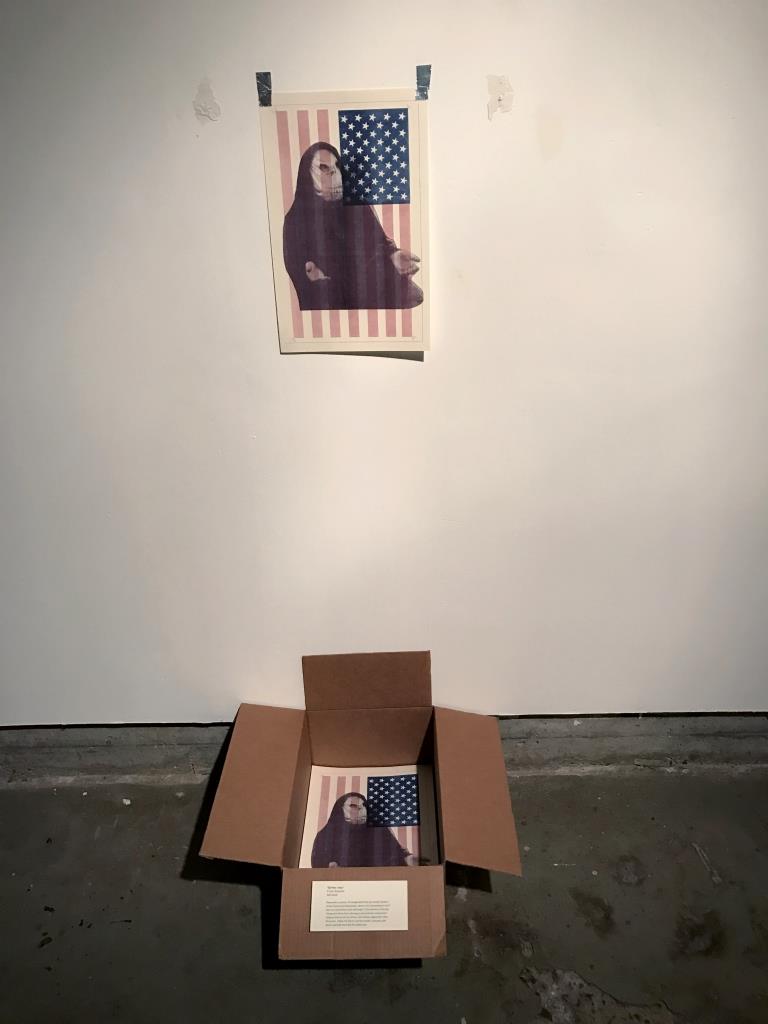

Installation view of Bleed&Burn at the Soap Factory in Minneapolis, January 2017. Photo: Alexa Horochowski

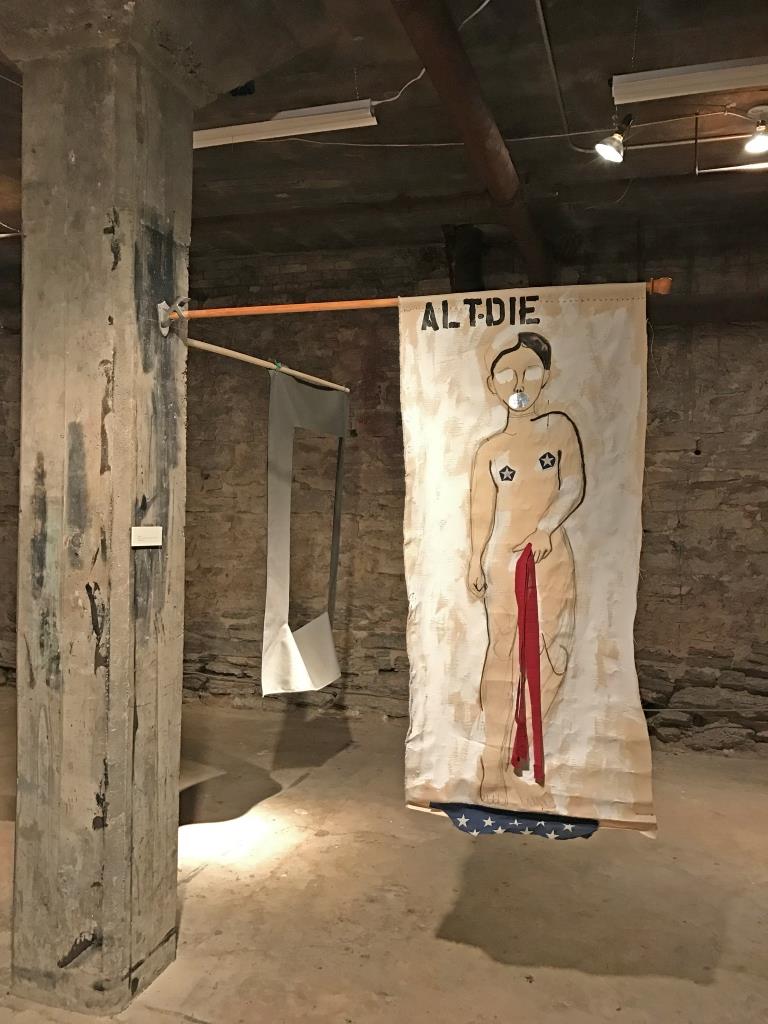

Front to back: Installation view of Eunice Pitts, Flag, found flag, ink, canvas, thread; Gudrun Lock, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, mixed media; Alexa Horochowski, Hysterical FANATICISM/Apathetic TORPOR, two rugs (made in Turkey), spray paint. Photo: Alexa Horochowski

For Bleed&Burn the artists’ chosen flag designs cover a tonal range of political commentary, from nuanced critique to polemics. Some reimagine Old Glory, but many others take altogether non-American, even absurdist spins. On view are flags created with textbook theories of art history, kitschy commentary on money, clever Marxist messages, quilted flags, and hyperbolic use of the word “fuhrer.” Perhaps the most invigorating works come from Sarah Petersen and Sam Gould. Petersen’s Ante hangs vertically, a flag of roughly sewn, triangular, clean white sheets that, given the title’s likely allusion to the antebellum South, converge in the center in a recalibration of the Confederate flag. With Of Thee I Sing, Gould gives audiences risograph prints of Old Glory for us to burn and then bless their ashes with our intentions for growth.

Shown together, the gallery of flags brim with vim and vigor, but do so without direction. And that speaks to the larger question: we know exhibitions of art, but what are the subsequent actions of art?

Artists have long been gadflies to authorities, but, beyond symbolic protest generated by our exhibitions of work, what do we have to show for it?

Horochowski addresses the challenge by encouraging the duty of passing the baton, however we can. “These flags are a first-response to what seems like an insurmountable problem,” she says, “a practice-run, done within three weeks, during holiday break, by several educators and other artists compelled to do something. We express something and hope it can lead to a better place, or to someone else doing something that leads to a better place.”

Chief Justice Rehnquist’s dissenting opinion in Texas v. Johnson pled for the sanctity of the flag, which, for “more than 200 years of our history, has come to be the visible symbol of our Nation [that] millions and millions of Americans regard with an almost mystical reverence.” Representations of Old Glory repeat through recent art histories, often uncloaking Rehnquist’s high-flying, weatherworn patriotism to lay bare true and old stories of these united states.

David Hammons, African American Flag (atop the Studio Museum of Harlem), 1990.

Fritz Scholder, Last Indian With American Flag, 1970.

William Pope.L, Trinket, 2008.

A newsfeed of other such flag works: for Forms in Space, Roy Lichtenstein renders the US flag, not for its triumphalism but for its graphic rigor; with What is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag? Dread Scott dares audiences to tread across the flag to complete the aesthetic experience; the colors of Black Liberation in David Hammons’ African American Flag memorialize the excellence of solidarity; William Pope.L’s Trinket lets the physical heft and theatricality of American jingoism lead to the flag’s own deterioration; the vigilant figure facing us in Fritz Scholder’s Indian with American Flag reminds us to consider the land itself; Stanley Forman’s Soiling of Old Glory captures an essential caricature of our history as a nation.

Preferring to revere the mystical qualities of the flag amounts to immediately covering your eyes after first seeing Forman’s photograph, whistling, and walking away as if never seeing it. Flag desecration done right burns away the comfy wool slung over our eyes.

The arts, in themselves, though do not serve as de facto saviors. Exhibitions of “radical” ideologies often masquerade as action, symbolizing transformation while doing nothing to effectively bend the greater moral arc. John Berger, the late, great teacher of art and capital, understood mystification simply to be “the process of explaining away what might otherwise be evident.” 2

Institutions and marketers are key culprits. For example, the chic polemics of an exhibition like Richard Nonas’s The Man in the Empty Space, mounted by MASS MoCA in 2016, serve to draw audience eyes away from the fact that Steve Mnuchin resigned from the board of MASS MoCA after PEOTUS nominated him for Treasury Secretary. Closer to home, we can appreciate the challenge of even tracking causal relationships between exhibitions and actions, with projects like Jonathan Ferrara’s Guns in the Hands of Artists, which Public Functionary hosted last spring. What are the non-symbolic civic impacts of such a staunchly postured show of provocative rhetoric? Exhibitions finish projects by establishing symbols of transformation, ideally inspiring separate actions to gain success non-symbolically. How can art be held accountable to the achievement of its own goals?

When we have events like Bleed&Burn at the Soap Factory, sending jolts through our comfortably held ideals of justice and constitutionalism, questions about art’s impact on society receive renewed relevance. There’s a sense of both urgency and malaise in the air today, as if we’ve been stunned and now it’s time to choose between fight or flight. Events in the Twin Cities have been cropping up, occasions for us to assemble and figure out what is really happening to the United States of America.

Artists have long been gadflies to authorities, but, beyond symbolic protest generated by our exhibitions of work, what do we have to show for it? Artists often identify problems so that audiences, other people, will solve them. The mantra is educate, agitate, organize, and the first two are easy. We can pass the baton with earnest hearts but only if we see who picks it up and cheer them to the finish line. We can further remedy the uncertainty of art’s impact by actually coordinating audiences to transgress non-symbolically. Art is never enough, or alone, and democracy is not automatic.

Howard Zinn put it flatly: Congress never passed constitutional amendments because they “thought one day, ‘Hey it would be good to have equal rights.’”3 To ensure the achievement of social progress trumpeted by an artist, the work of their art will be non-symbolic transgression. The vanguard movements of art in our time will employ symbols to embrace imminent and productive lawlessness.

More exhibition information: Bleed&Burn is organized by Alexa Horochowski and Crystal Quinn; the exhibition runs from January 14 through January 21 in gallery 4 of the Soap Factory in Minneapolis. Participating artists: Katy Collier, Katinka Galanos, Sam Gould, Geoffrey Hamerlinck, Guy Henry Mueller, Alexa Horochowski, Crystal Quinn, Channy Leaneagh, Janet Lobberecht, Gudrun Lock, Sarah Petersen, Eunice Pitts, Stephen Rife

For Bleed&Burn, the flags and documentation of each flag’s burning will be made into a book published at Beyond Repair, bookshop and publishing site located in the Midtown Global market, 920 E Lake St, Minneapolis. A flag-making workshop took place at Beyond Repair, January 15, 2017, 12-4 pm.