Ha!: On Comedy, Performance, and Laughing for the Right Reasons

Lessons from five years of stand-up: on writing and rewriting, reading the room, and how genuine and uncoerced laughter can fuel the process for change

I’m sitting down rewatching footage from my first hour-long show. I’ve waited a couple months for the footage, and as I sit back watching myself perform, I realize the show was good but I could never post the video online. There are moments when I flub a line. Points where I don’t let the audience finish their laughter before I continue the joke, even moments when I can tell that I’m trying to remember what the next joke is. Maybe I’m nitpicking. Maybe I’ve never seen myself perform for an hour. I waited five years for this opportunity, and it was good, but it was just the beginning. I still have a lot of work to do. Every show will just be another part of this process I’ve committed myself to. The maxim I learned in film school rings true: writing is rewriting. And even in this moment, with all the years that have come with it, this process must continue the way it started.

On October 3, 2017, I performed stand-up comedy for the first time, and in doing that, did a performance for the first time in my life. In the five years since, when people asked what got me into comedy, I have often stated this mantra:

When I turned 25, I told myself I would do all of the things I always wanted to do but didn’t have the courage to do. I cut my dreads off, and then a month later, I went to a comedy open mic. I told myself if I wasn’t the worst one then I’d keep doing it, and sure enough, some white guy in a suit went up and did an entire set about how bad his farts smelled. I told myself, “I’m funnier than that guy.”

This stream of words has justified something that I didn’t think I could do for years, but knew deep down I was meant to do. My whole life I wanted to make people laugh. I was always the clown of the group, the joker of the family, the kid who used his wit and jokes to fend off bullies. Comedy is many things for me: an escape from reality, something that keeps me rooted in reality, a coping mechanism, and sometimes an arbiter of trauma. I was raised by a poet, who once referred to comedy as my poetry. This idea has stuck with me since she said it. Comedy as an outlet, not just for creativity, but for many things.

On my 24th birthday, I went to a protest against a proposed youth jail. A person I met on OkCupid suggested I come to the noise demo, and I bought a case of water bottles and came through. Right off the bat, I was out of my element, yet exactly where I needed to be. The idea that Trump could be president was on everyone’s mind, but Minneapolis was gearing toward something big, and this protest falling on my birthday filled me with a sense of urgency I hadn’t had. Here I was, marching in the middle of the street with people I had never met before, struggling to hold onto these water bottles, as more people took some it became more cumbersome to carry until, finally, at the end of the protest, there was one last bottle of water. Mine.

I spent a large part of the year reading leftist political theory and learning of the history of my people’s liberation struggle, something I was familiar with and had learned about, but never by diving into the fine print. The grassroots, underground, Black and Brown, queer and trans details that the education system and the media doesn’t tell you about became more and more visible when looking past the harmony, civil rights-era nonviolence that gets propped up to the masses. The fight for change was there for me, but then it became something that is there for me always. A process.

When I told jokes for the first time, I was a newcomer in a world that felt like it was going to burst. Trump had just spent a year in office, and several Weinstein allegations had surfaced. While this was happening, some spaces where I could perform were filled with people telling the most racist jokes to bars of people they’ve never met at like 9:30 at night. Comedy, this thing I needed to gain confidence in order to do, had seemed the antithesis of what I had learned about. I quickly realized I didn’t want to tell jokes that punched down. Like many comics, I want my jokes to have substance. Like many comics, I want my material to touch people’s hearts. But mostly I want to make people laugh in a way that is uncoerced and brings change, because for me to do otherwise would go against what I learned before starting stand-up. To make the audience laugh from a place of unease would go against all of the unlearning I had to do. A coerced laugh isn’t a laugh at all; it is a trauma response. I didn’t want to traumatize an audience, I wanted to do what the comedian is supposed to do before anything else: tell jokes. If anything, I wanted to punch up. If anything, I wanted my work to continue the process for change.

In the last five years, I have focused my energy on not simply telling jokes, but creating collective joy. At any show I do, whether it be with Uproar Performing Arts or in other locations, I show up early, before anyone, because I want to feel the energy in the room so as to better have an idea of its shifts and movements. When I perform, I add in call and response and crowd participation moments, callbacks to hip hop traditions of keeping an audience invested, but also creating something we are all a part of. Creating community. I dabble in music, not because I’m good at it, but because the right series of words with the right series of notes can linger in someone’s mind and leave them with something more profound than a joke can. To some these can be gimmicks, and I’m sure any comedian reading this has been rolling their eyes. But to me the biggest gimmick is to be oppressive. As corny and fake as that might sound, that’s what I believe. What bigger hack is there than an oppressive comedian? In this field where freedom of expression gets championed, who is the biggest threat to that freedom? The audience, or the artist who uses their tools for evil? The comedian who wants to make anyone laugh, or the person who can’t read the room?

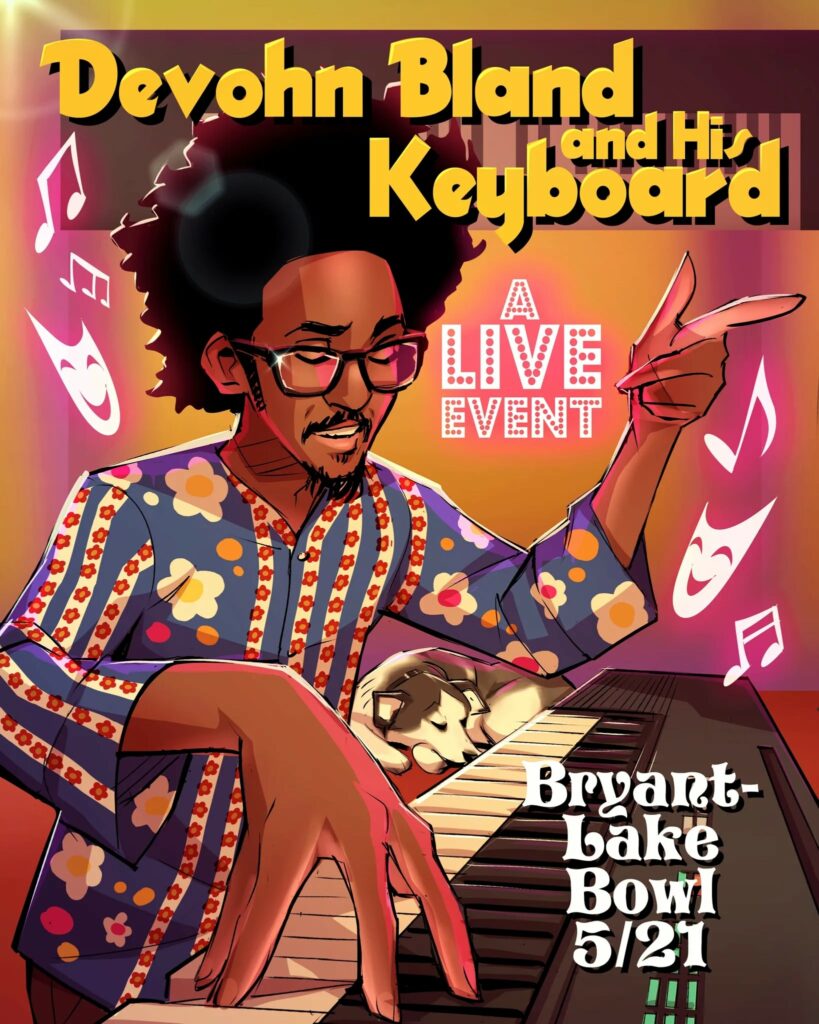

On May 21, 2022, I got to perform a show called Devohn Bland and His Keyboard: A Live Event (Act One). I didn’t know exactly what I was going to do when I applied for the Spit Take Comedy Residency, but I knew it would involve myself and a keyboard, and this comedic performance my mother tells me is my poetry.

The preparation for the show consisted of getting back into comedy a bit more actively after things had been shut down and starting to flesh out songs. It consisted of driving to Le Sueur for 20 minutes of crowd work to an audience at an Oddities Shop, letting an audience in Fargo know that I had soiled myself on the way there, and in doing this always rewriting what I had written. It consisted of videotaping my sets with cameras given to me by chance by fellow comic Joey Hamburger, and months later, Joey and I doing one of the most difficult shows we have ever been billed on at the Pourhouse. It consisted of living and discovering moments to talk about.

So much of figuring out how to perform and do art in the midst of the pandemic, in the aftermath of the uprising was asking: “How do I do the thing I do?” It consisted of watching Rudy Ray Moore films and the 1974 Moms Mabley film Amazing Grace, pioneers of Black comedy whose work was highly conceptual, witty, and politically charged in its own way. Preparation for this show meant seeing other shows that Spit Take put on, watching performers like Jacqueline Novak crush at the Parkway, and seeing my dear friend Comrade Tripp open for Emmy-nominated actor/comedian Ikechukwu Ufomadu. Preparing for this performance meant spending a fair amount of time as an audience member. It meant to be inspired again, not just to grind and write jokes. In order to create laughter, I have to be able to laugh as well. I can’t be funny unless I feel funny, and I needed to learn how to feel funny for an hour.

This was the first hour-long show I ever had to do, and my friend and colleague Kate McCarthy told me over the phone to make it the kind of show I’d want to go see. So I added songs. I painted a large canvas with the words “No Cops Allowed.” I started the show with a lil’ one-minute film introduction. There was a rug and my keyboard. I played the audience a song about my love for my girlfriend and a song about how Lindsay Graham looks like a bitch. I used techniques and tricks I had gained “volunteering” at Comedy Corner Underground. I used call and response calls I had created hosting the Uproar Comedy Open Mic. In almost five years of comedy, I’ve done everything from host, to feature, to guest set, to curation, production, sound, catering, songs. I’ve performed in basements, attics, kitchens, greenhouses, parks, breweries, clubs, bars, and even a front yard. For an hour I had the audience all to myself, an audience that seemed to consist of all of these different audiences molded into one, in this beautiful moment where all my lessons had come together. All I had to do was make them laugh at my jokes I had created, in all this time at all of these places over the years.

And I did. But also talked about my disdain for the cops, politicians, and white supremacy. I made the audience laugh about Lincoln being shot by a theater kid and stories about the worst bag of hot Cheetos I ever ate, and how my grade school D.A.R.E. officer’s son was a terrible person in high school and how I stand by that. For me, comedy feels like it’s easiest and purest when the show brings up memories of being the class clown in the cafeteria—your friends and you all sitting around eating school lunch, telling jokes and making someone spit out turkey and mashed potatoes because they couldn’t hold back the laugh. The venue didn’t have that on the menu, but I like to believe I got that response.

Behind me is five years of getting to this point. An hour’s worth of time. And I don’t always know what the future looks like, but I know I have more time to figure it out, and I know I want to get even weirder and more playful with this. I’m not the worst one at the shows, so I gotta keep it going. That’s the plan. To punch up, and to connect with an audience in a way that creates collective joy instead of forced unease. To perform on my own terms, to take all of these lessons and do the one thing I know I can do: be funnier and more profound than the guy who joked about his farts in a suit.