Painting a Place Between Invention and Memory

Scott Murphy's paintings are uncanny, resonant and utterly unconcerned with art world trends. For him, paint serves as a mode of communion, his own distinct way of seeing and showing the surrounding world and its almost-but-not-quite knowable inhabitants.

Ed. note: The italicized sections below are selections from the author’s interview with artist Scott Murphy.

TWO SELF-PORTRAITS IN SCOTT MURPHY’S RETROSPECTIVE at Duluth Art Institute particularly evoke painters’ self-portraits from centuries ago. In one, Late Night, the dark neutral background and the clear tight focus on the face calls those Old Masters to mind. But in Murphy’s version, that face isn’t lost in self-contemplation or even seriousness — it’s scrunched in irritation as felt hand-puppet sharks attack it, their button eyes gleaming with a blank gaze.

When did I start doing art? It’s just something I never had to be told to do. I made drawings, I loved drawing. In Stillwater High School, I had a great art teacher — I lived in the art room. I was excited about painting. But the art world of 1970s, I was befuddled by. The period that drew me was, like, Winslow Homer. I saw a Larry Rivers piece I liked, but . . . my high school art teacher thought of painting as primarily an expressive medium, almost as therapy—that he was helping people in distress. I didn’t discount that, but I also didn’t like the end result.

The other self-portrait, Dreaming of North Dakota, is in a Northern Renaissance mode, with dark headgear and strongly limned profile: the painter sits at the steering wheel of his car, a blown airbag spread before him; he wears a black hoodie, salted with the crushed fragments of his windows, and gazes down. It is a mortality image, taken from a real-life car accident Murphy experienced in North Dakota. Crowded into the car with him are some totem objects, favorite subjects in his paintings—a giant carp, a giraffe, an anvil.

I went to the U of M and got a BFA in painting, it was . . . exploratory. I like a lot of work. To put a restriction on art, that’s like putting your hand in the lake and saying you’re going to dig to the bottom. I like images you can tie some life experience to . . . but also abstract works, if the paint works.

This whipsawing, between humor and terrible vulnerability, is a theme throughout Scott Murphy’s work. He is a man in love with painting — with its history, what it can do. He uses invention as well as memory; he invokes the deep craft at the same time he mocks his own gravitas in doing so. Surrealism is at home in his work, in its original meaning: juxtapositions to create a world more real, because they’re more intense.

After college I didn’t really know what I wanted to do with painting. I took a job in the billboard industry, a union painting job. I painted all day. I did paintings for 17 years in a production mode. I did learn how to paint, how to be in paint. It was essential. I would have quit painting otherwise. We painted objects all the time. It was our job to sell things, make people want them.

It’s liberating to paint large. You edit things in your head, you choose what has to be there. When you’re in a sea of abstract forms [that make up the big images], and you’re mixing beautiful reds and purples, you get to realize how color works, how powerful it is. It kind of lights a fire in you, makes you want to paint.

There are incredible images in this show, some of which you can see in the slide show above. The paint serves as a way of communing with the subjects, seeing them in an intimate, structural way – and that’s crucial. The paintings are bemused, loving interchanges between an artist, working alone, with a world populated by people and animals, and even by (somehow) inhabited things–all of whom can be known as little and as much as he, the painter, is. Over the years this communion has become deeper and more resonant in Murphy’s work, freer and more heedless of what any others might think. You’re invited to look at these painted worlds and to take what you want or what you can from them.

The hardest thing to paint [for a billboard] is women’s faces. You can never do them soft enough.

____________________________________________________________

Murphy’s paintings are bemused, loving interchanges between the artist, working alone, and a world populated by people and animals and somehow inhabited things — all of whom are at once as knowable and mysterious as he, the painter, is.

____________________________________________________________

The painting, The Day the Wind Blew the Sun Away, is one of these mysterious images: a woman’s feet in black pumps, the heel counter standing a little bit free of her ankle, against a light-devouring black background—sky? Maybe? To the far right, there’s a sliver of the lemon-yellow of the very last of sunset, along what could be a horizon. And you’re there. You can feel your own feet in those shoes—it may be the detail of their loose fit at the heel that does the trick, or the odd specificity of the style, or maybe it’s the foreground lighting that somehow evokes that self-image in the mind’s eye. It’s an uncanny painting in which the strange elicits a powerful empathy.

[Painting signs] you’d be concentrating for eight hours every day on how to do a thing, how to paint this detail—you didn’t worry about “is this art?” That was something to think about when you were drinking . . .

In Elephant, two of the massive beasts plod through a snowstorm, heading southwest on Mesaba Avenue in Duluth — the street the big trucks take. One of the elephants is turning, close to the canvas, her hairy chin stark in the snowlight; the other is making his way methodically down the wide street, confident, it appears, in his route. Cars maneuver through the intersection, unfazed and unaffected by the beasts’ passage. Murphy says this painting was inspired by a story he heard about one of the Shrine Circus elephants dying in a show down by the harbor, after which it had to be hauled by flatbed semi up Mesaba, out of town. In the painting, the near elephant’s eye is wide awake but reserved, watering a little from the cold.

The thing we’re blessed with now is the internet. We don’t have the filter of art magazines. . . I see a lot of things online that I like—there’s this Finnish painter, he did a fabulous painting of an oversized bull, huge horns, standing on an I-beam, surrounded by birds. I love photography, but I’m a bad photographer. Some images just have so much power, and it’s mysterious . . . the other day I was looking at a photo of a heron and next to it a blurry dancer. That image is etched in my mind.

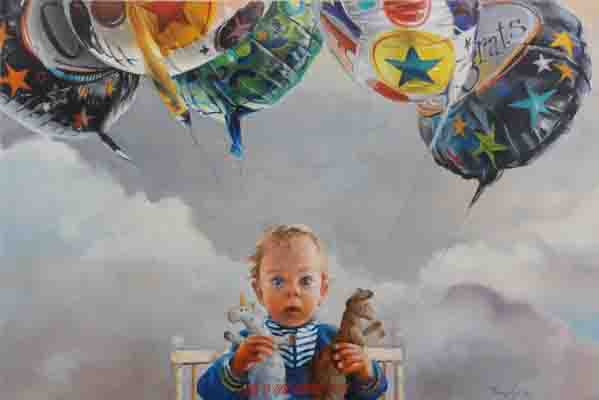

U-118 is the name of the submarine that fills the distance in Murphy’s painting by the same name. It is a U-boat that washed up on an English beach—here, it’s rusting, vast, heaved up like a whale and towering over the people surrounding it. A long line of eternally waiting people stretches in front if it—people who must wait for someone who has to give something to them, who do not have. They are the color of the streaks of rust on the sub’s hull. In the foreground, right in your face, is an insanely lovely, goofy-joyful toddler with a screwy smile and dandelion hair, beautifully painted, accompanied by a pair of squirrels. We are definitely in a Murphy universe. And while in this universe, the natures of things may not ever be explicit , they are certainly not hidden. We know who we are.

____________________________________________________________

Related exhibition information:

Broken Threads. Lost Causes is a show of new oil paintings done in the past year by Scott Murphy. The opening reception is December 5, 5 to 7 pm, in the George Morrison Gallery of the Duluth Art Institute (in the Depot at 506 W. Michigan St. in downtown Duluth).

____________________________________________________________

About the author: Ann Klefstad is an artist and writer in Duluth.