1001 Buddhas: the week in dance

A dispatch from the rehearsals for Ragamala's world premiere '1001 Buddhas: Voyage of the Gods,' bharatanatyam dance and taiko drumming exploring the cross-pollination between Japan and India as Buddhism spread through Asia.

This weekend Ragamala’s latest creation, 1001 Buddhas: Voyage of the Gods, opens at the Cowles Center. Ragamala, led by the mother-daughter directing team of Ranee and Aparna Ramaswamy, is probably the most decorated dance company in Minneapolis, but even so, when I haven’t seen them in a while, I forget just what a whirlwind of dance, music, and cross-cultural collaboration they spin.

The taiko drummers of Japan-based Wadaiko Ensemble Tokara raise their sticks high to strike, Ragamala’s own South Indian ensemble leans in, dancers flex, and in a minute the room is alive, the floor bouncing. Studying the face of her drum, Yukari Ichise seems to be watching the beat rather than listening, and watching her, you can imagine seeing sound, the ripple of it spreading out across a larger drum or a lake in which everything swims. The ripple moves through your chest, a beat sheltering the inner beat.

Amid this hurricane, the dancers stand still—or almost: a closer gaze detects their revolution, as smooth as if they were statues and you were walking around them. In fact, they are statues, their shapes derived from Hindu deities who mingle with one thousand and one Buddhas at the Sanjusangendo temple in Kyoto. The Ramaswamys studied the carvings and then animated them—imagining “how they would move if they moved,” Ranee says. This might deliver a static dance, but in combination with the taiko drumming, the effect is synesthetic and prismatic, with still sculpture, motion, and sound flickering over the stage.

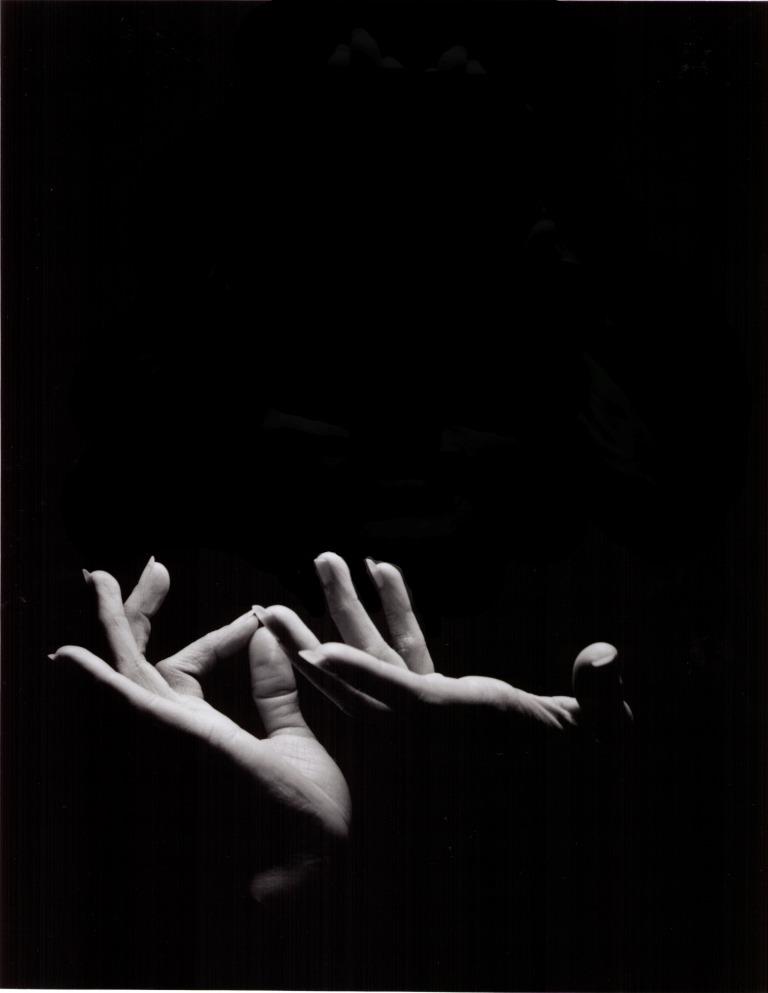

As the dancers shift through this musical space, their hands bloom and grip into forms as specific as an alphabet. (In fact, these gestures, called mudras, are an alphabet, which bharatanatyam dancers usually use to translate a text into motion.) Fluttering doves, or a finger crooked like a snake about to strike; a musical instrument held up to the side, fingers lightly playing the stops; prayer; unraveling a skein of some rich-colored silk yarn, measuring a bolt of cloth; or pulling an arrow backing to the ear, sighting to the horizon; a sunburst, a hand on the rein; a whole-hand pinch, closing like the tentacles of a cuttlefish; a pistil moving among petals. Or the hands simply angle down, the last touch to a pose in which the dancer leans forward over one leg, as if flying; you can almost see rainwater running from her fingers.

Their faces also speak, with snarling ferocious looks, the mile-piercing gaze of one who knows where she is going, or a trembling revelation, a dawning tenderness. The eyebrows in particular communicate: bharatanatyam emotions move through those muscles, which (you’ll notice if you try moving your eyebrows now) have to do with perception, apprehension. The characteristic eyebrow flutter is a sort of breathing of the intellect. “We like to joke that we can never get Botox,” Aparna laughs.

______________________________________________________

Ragamala’s dancers are once exact and flexible, and their distinct qualities shine here—fire, wind, lightning, the moon, essential and changeable, like the deities they represent.

______________________________________________________

The detail of every face and stance keeps the eye moving; the Ramaswamys have invested each position with more specificity than you can ever entirely catch. When Ranee and Aparna’s solos end, Ragamala’s four-woman corps—Amanda Dlouhy, Jessica Fiala, Tamara Nadel, and Ashwini Ramaswamy (Ranee’s daughter and Aparna’s sister)—break unison, each taking a slightly different pose. I’ve seen these four deployed as background to Aparna’s unparalleled brilliance, but in the past few years they’ve all come into their own (and almost all earned McKnight awards for their dancing). Together since 2006, they’re at once exact and flexible, and their distinct qualities shine here—fire, wind, lightning, the moon, essential and changeable, like the deities they represent.

These deities, both male and female, guardians and goddesses and demons, have traveled thousands of miles and years between India and Japan; retracing that thin-stretched thread of cultural and religious tradition is Ragamala’s inspiration here. Translation becomes at once an anchor—it’s important to them to get the gestures right, to represent the gods correctly—and a source of freedom, especially in the music. Rather than being bound to the usual South Indian structures, here the dancers get to explore “a field of music that comes and goes,” Ranee says, an immersive space, Wadaiko director Art Lee adds, in which the dance becomes “rather than a story, almost an anthology.”

As I watched rehearsal, my attention kept shifting from music to dance and to the spaces in between. I would watch the drummers, then try to take in every detail of a dancer’s pose, but in the meantime someone in the background shifted and I lost the shimmering details she held out a moment before. I could listen to the music for a bit, trying to catch a rhythm that sounded simple but broke into triplets here and there, regular yet beyond easy understanding. Then the entire dance turned and I looked at the curled-up toes of this dancer, the spirit-level arms of that one, but all the time the eyes of another looked out at something I thought I also might see if I looked hard enough. The overall effect is of a mystical order imperfectly perceived—a jeweled ascent in which one goes on, rewarded, yet still seeking.

______________________________________________________

Related performance details:

1001 Buddhas: Voyage of the Gods presented by Ragamala Dance, will make its world premiere March 22 through 24 at Cowles Center for Performing Arts in MInneapolis. For more details and ticket information: http://www.thecowlescenter.org/calendar-tickets/ragamala-dance

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl was recently published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She writes a weekly column on dance for mnartists.org.