What Do You Want to See?

After a week packed to the gills with dance - burlesque, avant garde, modern - Lightsey Darst found them all to be precisely what, in the moment, she wanted to see: "How did these performances make me so want what they had to offer?

What do you want to see?

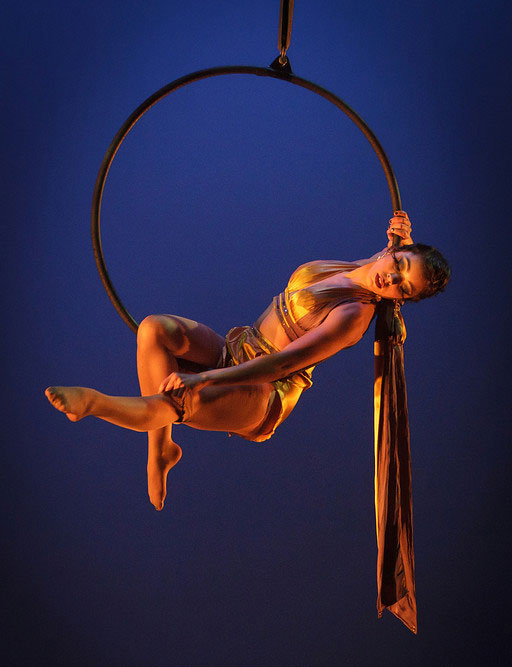

Thursday evening: freezing cold outside, but it’s hot inside the Ritz as Caramel Knowledge and other lovelies get down to business, or pasties and a g-string, at the Minneapolis Burlesque Festival. “You don’t need the bandaid pulled off slowly!” hostess Gina Louise exults after the first tease, and no we don’t: the audience laps up every wiggle and twirl. Unfortunate verb choice, I know, but that’s burlesque: the art of the inappropriate. Also the art of slipping off a lichen-green silk robe like a second skin (Lady Jack), or dropping a glitter tailcoat to reveal a labial red train, then peeling the whole thing away in one quick gesture (Gin Minsky); or ruling the stage in a Goth trance, a princess of dark magic (Musette); or spinning on a hoop in sateen light, lying back in its crescent moon curve wearing nothing but stardust (Josephine Belle). The tease, the clothes, the lingo: Ulla Umlaut, “the velvet squeezebox,” “puts the um in umlaut,” while Cherry Typhoon, “the bitchy geisha,” is “chubby and she’s tangy.” She’s both, and she earns her name when she whips off her dress and makes it all go: frills, tassels, flesh. Wonderful flesh! We spend so much time mortifying and regretting it, but burlesque puts all its jiggly bits on display, which turns out to be hilarious as well as sexy. Blanche DeBris’ six-minute strip version of The Sound of Music made me laugh until I had nothing left in me, a genuine catharsis. Foxy Tann and the Wham Bam Thank You Maams, Vincent Van Gogh Gogh and his astounding ass twitch, Pouty Petals’ “Maneater” routine (pasties and g-string dripping red streamers)—sheer and see-through delight.

Friday night at the Red Eye: lights come up on the total design of Chris Schlichting’s Matching Drapes. Wallpaper by Terrence Payne covers part of the back wall and stage in a slide of black-and-white busyness, its forms drawn from the hives and wings of Victorian natural history. Seventies schmaltz loops in the background, its bass turned just loud enough to din at the edges, and alternates with suburban night sound—crickets, the rattle of a commuter train. In this dancers caress, dart, revolve, prance, reveal. They come close to each other, drawn, but they never touch, held in orbit by mutual magnetism. They especially gaze at the audience, as if to say “This is for you,” this babying of one’s own elbow, this fey flexion of a wrist, this slow stir of a hip. Schlichting seems to love joints, and he chooses dancers who use them with luxury and clarity: Mary Ann Bradley, Krista Langberg, Laura Selle Virtucio, Dustin Maxwell, Max Wirsing. It’s wonderful to see Virtucio disarmed, as it were, with nothing but her stellar motion to express. And Dustin Maxwell is the kind of dancer who can emerge from an upstage alcove (with its own wallpaper and lit chandelier) thirty minutes into a dance and give it a new life—smooth, mesmerizing, seemingly riding a current in the air, illustrating what’s already there. When the show was over, I found clapping for it an unwelcome effort; I wanted to keep sitting there, glazed, purring like a satisfied pussycat.

Saturday finds a crowd of people stuffed pell-mell into the basement of the bodega Los Amigos, sitting on each other’s coats, for Angharad Davies’ Throb in the penultimate Outlet performance series show. We’re delighted right from the start as her mass cast comes out—16 or so women in unflattering but somehow badass safety jumpsuits, a mix of noted troublemakers (Megan Mayer, Kenna Cottman, Stephanie Stoumbelis) and new faces. They strut, they mug, they drill into complex patterns, they click-step like a color guard. They gather in a corner, gyrating and making faces (now sexy, now horrified); they die to the tenor aria “Nessun dorma,” then promptly wake up again, giving us the aw-yeah nod, like “I totally nailed that death scene, right?” Yes you did. The pleasure of symmetry and order alternates with the pleasure of individual quirk; the performers’ happiness radiates throughout. (And can I just say how nice it is to see such a diverse cast for a piece that’s not “about” “diversity”?) When the piece ended—with a mad dash and a moon-landing jump at our feet—the spectator next to me exclaimed, “I loved that! It was awesome!”

______________________________________________________

Schlichting’s achievement might be the strangest, as watching Matching Drapes is a bit like—and I mean this in the best possible way—watching some very symmetrical cats lick themselves.

______________________________________________________

All these performances were wonderfully gratifying: they showed precisely what I wanted or even needed to see, I felt as I watched them. In fact, I could have happily watched more (of everything but the burlesque—I would have ruptured myself if I’d laughed any more that night), and I would happily watch any of them again. The wonder of it is that I didn’t wake up on Thursday thinking, What I really want to see today is a lot of pasties. Nor did I wake up on Saturday thinking, Synchronized ladies in hazmat suits, that’s the ticket. How did these performances make me so want what they had to offer? Schlichting’s achievement might be the strangest, as watching Matching Drapes is a bit like—and I mean this in the best possible way—watching some very symmetrical cats lick themselves. So what’s the magic? Pure conviction? I don’t think I know.

But a contrast might illuminate something. The other piece on Outlet’s double bill was a solo in which BodyCartography’s Otto Ramstad gave the audience not so much something to see as something to witness—a transformation, an embodiment, that we take in with our whole social and physical being. Ramstad’s improvisatory motion reminded me at one point of St. Sebastian, at another of the Discobolus, but I tossed these aside as probably accidental. More pertinent to the intention of the piece, I think, was Ramstad’s animal physicality—in the moment, for example, when he tasted the air like a lizard. He exhibited an edenic state, untrained, unrestrained, that brings our own muted physicality into question.

And here BodyCartography perhaps inadvertently crossed a line. Ramstad was nude save for his sneakers—hardly notable, but the people around me frosted over in reaction to it, as if his nudity constituted an assault. Did it? He was on the same ground as the audience, close up, and in motion. When he loped across the front, swinging one arm like an ape, he confronted the audience with a naked male human animal. When he walked into the audience to embrace various people, I saw stony faces all around. “What if someone had been abused?” a friend asked later. After the show, one spectator brought up the idea of continuous consent, saying that merely sitting in an audience does not imply agreement to anything that might occur. Only a few people left, so apparently Ramstad had that consent. But he was pushing its edge—which is strange, because a few years ago naked people in transformative states were standard fare in local dance. What’s changed?

It’s interesting to see what people want elsewhere; thus Rosy Simas launched Échange, the first Montreal/Twin Cities dance exchange. I went because I wanted to see Deborah Jinza Thayer’s new work, the first since “wrestling with a Cadillac” last year, as she puts it. But I botched it and saw only one of the mixed bills (yes, it was the kind of weekend where you can see four shows and still feel like a dance wuss). Based on the thin evidence of Georges-Nicolas Tremblay’s Interdit de s’embrasser, Montreal likes it rough. A man covers a woman’s face and leads her backwards; elsewhere, the dancers seemed to enact interventions on each other, kicking, climbing, shoving. Later, they crash repeatedly onto the stage. Well, it’s a start. Simas promises more of this worthy venture in the future.

From the Minneapolis side of the exchange, I also saw Sally Rousse’s Freemartin Twins, which looked better than I remember (the work premiered in early 2012). Rousse plays with the opposition between symmetry and partnership here, between kin and love. Sprawling, sidelong embraces give way to codified oppositions as one unfixable creature—Rousse, the freemartin—ends up discarded, splayed half under the curtain. I could have seen more.

This coming weekend, one company hopes to convince Minneapolis audiences to see them: Saint Paul City Ballet. Crossing the river to perform at the Cowles, the company brings high spirits, new contemporary work, and need: their financial situation looked so grim at the beginning of the season that they almost shuttered the company for the year. But “the board took a leap of faith,” says co-Artistic Director Allison Doughty Marquesen, and let them go on. SPCB carries on the Andahazy tradition, the oldest ballet line in the Cities, and they’re more classically based than Minneapolis’s two chamber ballets, so the new work they’re bringing to Minneapolis was “a stretch for the dancers”—but a good challenge. “We’re better than we were,” Marquesen says. For this run at the Cowles and their future, “Everybody’s just crossing their fingers.”

______________________________________________________

Noted performances:

- Saint Paul City Ballet will perform at Cowles Center for Performing Arts February 8 – 10. For more information: http://www.thecowlescenter.org/calendar-tickets/saint-paul-city-ballet

- Outlet Performance Festival concludes Saturday, February 9, with performances by Wetterling and series creator and curator Jaime Carrera. For more on shows past and present in the festival: http://outletperformancefestival.tumblr.com/

- Minneapolis Burlesque Festival took place on January 31 at the Ritz Theater in Minneapolis.

- Rosy Simas Dance’s Échange, Montreal/Twin Cities dance exchange, took place in the Tek Box at Cowles Center, February 1, 2 & 3.

- Chris Schlichting’s Matching Drapes was on stage at the Red Eye Theater in Minneapolis January 31 – February 3.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl was recently published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She writes a weekly column on dance for mnartists.org.