Poetics in Pandemics, Poetry Against State Violence

Poet and editor 신 선 영 辛善英 Sun Yung Shin delivers a manifesto on the necessity of poetry in the time of pandemic and racist state violence, making an urgent case for language work as a technology against erasure, as a form of spell-casting, as a space for claiming erotic power and possibility.

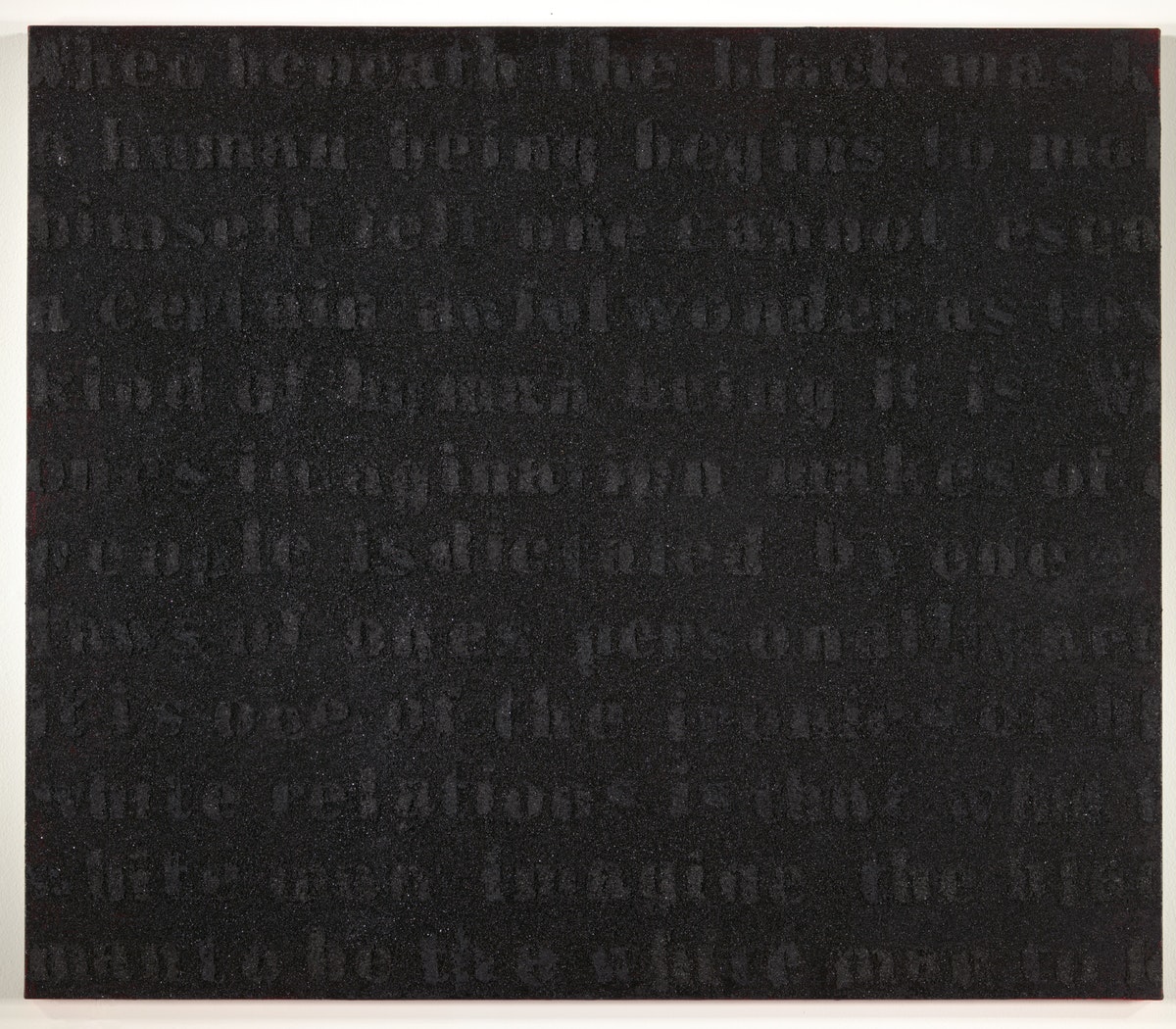

“A poem is a dam against erasure.”

Solmaz Sharif

“The place in which I’ll fit will not exist until I make it.” –

James Baldwin

We mourn and seek justice for George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Kayla Moore, Miriam Carey, Shelly Frey, Tamir Rice, Michelle Cusseaux, Philando Castile, Alberta Spruil, Jamar Clark, Michael Brown, Tanisha Anderson, Trayvon Martin, and so many more the police and its surrogates have murdered in this country. But nothing will bring them back to their loved ones. A poem is a dam against erasure, but nothing is a resurrection for those we have lost.

Human civilization, encroaching on wild animals’ habitats, has unleashed zoonotic viruses like the novel coronavirus of 2019. And will continue to do so.

A virus can kill you dead directly.

Poetry is not a vaccine.

Poetry is not a flak jacket.

Poetry is a machine made of voice or paper.

Poetry carries ideas; ideas make their homes in humans, passed from one to another.

Language can kill you indirectly. It is not a gun but it is the order from one mouth to the mouth of the man holding the gun. It is the writing of a policy that puts a garbage dump in one neighborhood and not another. It is in a small book, a passport that means life or death.

What to do, as language workers, with our language work?

I think about poetry’s nimbleness, its ability to be swift, immediate, and proximate. Its usefulness in confined places, such as Angel Island from 1910-1940 when as many as 175,000 Chinese immigrants were detained and processed there because of the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882). Detainees were held for weeks, months, sometimes years, and they wrote hundreds of poems on the barrack walls. When I visited some years ago, I felt strongly the presence of their bodies and spirits rise from these poems-in-the-walls. Their anguish was still present.

A Chinese interpreter at Angel Island wrote this poem about a woman who was denied entry into the United States after being interviewed, “In her eyes he saw his parents,” as well as “the taint of blood that shaped his life / and brought him to this prison.”

*

Words are preserves of human history, of daily use, of the clash of cultures, of conquest, assimilations, evolution. Linguists say there are 7,099 languages. A 2018 article in National Geographic, “The Race to Save the World’s Disappearing Languages,” by Nina Strochlic says that “Between 1950 and 2010, 230 languages went extinct, according to the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Today, a third of the world’s languages have fewer than 1,000 speakers left. Every two weeks a language dies with its last speaker, 50 to 90 percent of them are predicted to disappear by the next century.”

Against disappearance, against forgetting. Endangered languages are priceless, because they are embodiments of epistemologies, and micro, hyper-local knowledges, ways of knowing, in many cases passed down for generations, indistinguishable in some ways from the land and natural systems in which the speakers of the language made their lives. To kill a language is to commit a terrible epistemicide. Memory can be a form of love, a form of justice. Poetry, like monuments in public spaces, is caught up in the politics of public memory as well as the secrets of private memory.

Poems, like the magnificent Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem “The Bean Eaters,” published in Selected Poems in 1963, elevate an ordinary couple’s daily, private life and memories to a kind of abundance, with its ellipses and its long last line:

And remembering …

Remembering, with twinklings and twinges,

As they lean over the beans in their rented back room that is full of beads and receipts and dolls

and cloths, tobacco crumbs, vases and fringes.

*

This time of rising plague, ongoing white supremacy and terrorism, state violence, ongoing police murders of Black people, Native people, and citizens and residents is an opportunity to make more visible and audible the ethical considerations of language, and, where and when appropriate, to find joy, life, and pleasure in the mind of a poem, poems.

In Audre Lorde’s important essay, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” which was originally a paper delivered at the Fourth Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, Mount Holyoke College, August 25, 1978, published as a pamphlet by Out & Out Books and reprinted in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde (The Crossing Press, 1984), she writes about power:

There are many kinds of power, used and unused, acknowledged or otherwise. The erotic is a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling. In order to perpetuate itself, every oppression must corrupt or distort those various sources of power within the culture of the oppressed that can provide energy for change. For women, this has meant a suppression of the erotic as a considered source of power and information within our lives.

For Lorde, the erotic is depth; it is a kind of energy:

The erotic is a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings. It is an internal sense of satisfaction to which, once we have experienced it, we know we can aspire. For having experienced the fullness of this depth of feeling and recognizing its power, in honour and self-respect we can require no less of ourselves.

Poetry can be a way of honoring that power, that fullness. A poem can be against exile. A space in which to imagine, to at least momentarily banish the ways we live in exile of ourselves, our deepest feelings, and for too many people in forced migration, our homelands.

*

English is a refuge and a weapon. The Roman alphabet is the Devil’s mischief. 26 symbols have given birth to, through collective human usage (uh, and Shakespeare), one million words in the English language alone. If that’s not magic from the limitless chthonic world, I don’t know what is. English is currently the market-dominant language on the planet, and anyone who uses it to write with should treat it like it’s an enchanted forge—magical, dangerous.

I think most poets are asking, or answering, implicitly, in every poem, What can language do? What is this material, this medium? Like any medium, it has its humble uses (clay fire-hardened into ceramic can be used to make art, or toilets, or a toilet called art.) Or perhaps this is an American affliction, as everything is a commodity and poets are constantly being asked, “What does poetry have to offer? Why should we read poetry? Why should we teach poetry?”

Language is magic. Spelling is literally making spells. A poetry practice is an inherently political practice because all language is political and poetry, as much as anything else, is a human responsibility. As human beings, poetry can help us heal, restore us to wholeness, remind us of our indivisibility from all life on the planet. Learning our languages’ histories helps us respect the humans who kept them alive, because language helped keep them alive. In this ongoing time of state violence, racism, and plague, we can allow ourselves to be reminded that language is alive, and that poetry, whether in private or in public(s), can be a form of premonition, astonishment, communion, and homecoming.

False dichotomies divide us from ourselves, and from our futures. “The aim of each thing which we do is to make our lives and the lives of our children richer and more possible,” and “The dichotomy between the spiritual and the political is also false, resulting from an incomplete attention to our erotic knowledge,” wrote Lorde.

We need to exercise and protect the freedom to make spells, to throw hexes, to make verbal webs of protection. To make space for possibility. To use our power.

Lorde wrote about power, “Recognizing the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world, rather than merely settling for a shift of characters in the same weary drama. For not only do we touch our most profoundly creative source, but we do that which is female and self-affirming in the face of a racist, patriarchal, and anti-erotic society.”

Our society’s sense of a commons is impoverished; capitalism colonizes even the inner space of the imagination. Korean American poet Myung Mi Kim ends her poem “[ruins library]” from Penury (Omnidawn, 2009) with lines that describe some of the divisions of our pandemic moment, and the racialized capitalism of America’s civic project in general.

where preventable diseases rampant

where the need is window screens and sewer covers

where for the good of the very few and the suffering of a great many

As a poem brings letters together to bring words together, small shapes stitched together as for a garment or a temporary shelter, so may we as people come together to create sanctuaries and refuges for each other, by any means necessary.