The Audience’s Work Is to Listen: On Communication and Chaos

On misreading, over-translation, nonverbal understanding, and the pitfalls of legibility

Maybe for us to understand each other we need to be acquainted. I am a blonde, cisgender woman, near 40. I am the primary caregiver/parent to a healthy child, nearly three years old. I am a dance artist. I am otherwise unemployed. My housing situation is currently shifting to something that I believe will be healthier and I don’t know what this will be yet. My dearest friends live outside of Minnesota. I’m sitting at a computer, wearing a gray sweatshirt and vintage wire-rimmed glasses. Behind me is a plant and a banister railing. That’s as clear as I am comfortable being now.

I keep saying this, but I feel intimate trust with Dolly Parton. She is a person who I’ve never met and who has strong boundaries around what is personal and what is “in your face.” Here too, certain words are chosen and put forth. It is a surface for scratching.

To write to you respectfully, which is what I aim to do, I have to imagine somewhat who I think you are. I suppose you think about art or you are an artist? A dance artist? Or someone familiar with the Walker Art Center? You also have a computer or phone? And a power source, likely at a home? I’m sorry I can’t hear you better.

Recently, I was reminded by a mentor of traditions in which audience and performer are one, as music and dance have been one, indivisibly in relationship. I am also at the beginning of a MFA program, and have been thoughtless with the term “audience” in my writing. It is a habitual word choice that I am using to describe the complex beings who have not been a part of the collaborative process of making, though are collaborators in a final showing. Of course, that is just one functional definition for audience. The etymology signifies listening. In “Delegated Performance: Outsourcing Authenticity,” Claire Bishop describes how certain artists, such as Tino Sehgal and Santiago Sierra, use a perverse power in their art, to manipulate participating audiences away from honest responses and towards reactions of the artists’ own design.1 Vice President Harris’s voice—“I’m speaking”—is still ringing in my ears. With all these big egos—and capitalism—like Bishop, I have a hard time seeing how the relational field between artist and audience could be so spacious and level. Our perceived senses of power and control, or lack thereof, take up room.

It’s been a long time. It’s dark. I sit still in my own room. I always notice, and occasionally appreciate, the faint click that sounds before my furnace kicks on. I recently lost a friend to suicide. I didn’t anticipate it; it had been a long time since I’d seen her. If you’d asked me days before, I would have said her life was pure beauty. Looking back at her Instagram now, listings of her recent shows—she was signaling what was to come.

And what is? I am waiting to receive the performance manual from a canary torsi/Yanira Castro’s Last Audience. A printed copy in the mail from a show that was entirely performed by dozens of audience members each night. I wasn’t able to see it live, before the pandemic, but I will take the text and scores into my own private reality this winter. To manifest a production alone, within my space and abilities, held up by the hope that others will too. It feels important to see innovative permutations of dance, a medium currently silenced, or nearly. Unless… In my view, Yanira Castro is a thoroughly aware and perceptive artist, energetically open; she is also a Phase 1 collaborator with the Creating New Futures document and movement, “Working Guidelines for Ethics & Equity in Presenting Dance & Performance.” But, like the Gutenberg Bible, I wonder how the shift from social reading to solitary experience will morph our interpretations. Will the work attach to all of our personal limitations without the peripheral insight of others?

In Adrian Piper’s Funk Lesson’s (1983), a work with a similarly active audience, the social charge of the scene was prominent as white participants were taught through dance about Black funk music. Acknowledging herself as audience to her own work, she reflects in Notes on Funk I & II, “For me what it means is that the experiences of sharing, commonality and self-transcendence turn out to be more intense and significant, in some ways, than the postmodernist categories that most of us art-types bring to aesthetic experience.”2 Rearranging worth within art, she describes the listening and understanding made possible through bodies in dance. A synergistic route to connection. I wonder, did the art reviews respond in such tones?

And live artists, with various intentions and histories, have been trying to get close with audiences for a long time—using mirrors, untraditional spaces, by casting no professional performers, or casting one performer for each audience member, by creating structures for the audience’s agency and action, or the audience’s bewilderment. But even in the most guided, formal, proscenium events, the audience has prerogative and personal attributes, allowing them to notice and know the work as only they can. Audiences co-create: meeting triggers, adding side conversations, attending to physical comfort, evaluating new and old information. The artist’s platform is crowded regardless.

Overcrowding is amplified with art living largely on the internet. The World Wide Web makes for tight quarters. Physical bodies are flattened, and the value of vulnerability is undermined. We know listening is scarce, but we still shout into the dark—and truly, we need to. Social media has been a crucial tool for social justice and mental health lately. But you can’t build a home with only a hammer.

I miss wearing shoes. An internal voice says not to wear them in the house, but I think of them and their strength, support, authority. I was catcalled via scolding once: “Your shoes really announce you.” A misogynist’s director’s note for my performance of “young woman” in his theater.

And I miss being barefoot. Historic whispers of unbridled authenticity carry forward over marley. A ground floor to the fully sensorial experience that is dancing with others. Less acclimated dancegoers have been known to say, “You know…I’m not sure I got it, but…” Something was gotten. Does it need to be named? Although, when else do we practice understanding without demanding translation to an articulate, verbal narrative? And do we understand, even then? I say “we” because I believe I am speaking to my fellow artists who are also digging out of this dung heap, where we are not acknowledged as workers or contributors—but we know who can get away with inarticulations and blathering tweets.

The Dunstan Baby Language theory, as seen on Oprah, is a universal translation of baby cries, taking the guesswork out of that immature communication. It was not explained how infants’ needs were met before this 2006 airing. Likewise, advanced care directives are written as a safety net of communication for those unable to speak and make medical decisions for themselves when nearing the end of life. They are intended as legal and technical documents. They are also a space and a chance that not everyone receives. Can what one still needs to say, the ultimate significance of final moments, the poetry of a life become CliffsNotes? Does the statement achieve its goal or create an extra venue for miscommunication? Does it still hold true in the end?

In my own work, I’ve been interested in physically exchanging, meeting vulnerability with limited or no language. Ideally this makes openings for people—both collaborators and participating, self-selecting audience—to navigate asking for consent, and to respond in agreement or disagreement quickly, without the pomp and legality that is so prominent and preferred these days. Art producers like to suggest that audiences sign a waiver, even when the experience is fully exposed and participation is voluntary. When teaching physical practices in care settings, the waiver is ever-present. It’s hard to trust a body’s truth when the stone face of institutional power is leaning over your shoulder with a fountain pen of doubt. For safety’s sake, significant and precious time is given to clinical research—though two days is seen as sufficient time to train and be ready to teach a trademarked tai chi class, no matter one’s previous familiarity. Highly prescribed lesson plans assist mostly in describing a singular and perfect audience. In the name of safety, accumulative knowledge and accessibility are forgotten. Waivers and evidence-based practice are not failsafe, universal, or immediate; they can be unsupportive when we’ve had an accident or made an unfortunate choice. And they don’t reach into the darkest corners. We are capable of communicating on many levels, often simultaneously, but select few are legitimized or honored. I love the careful, even aesthetic, language around consent that has risen from kink, but the problem is not solved; rape culture is unfazed, strong as ever.

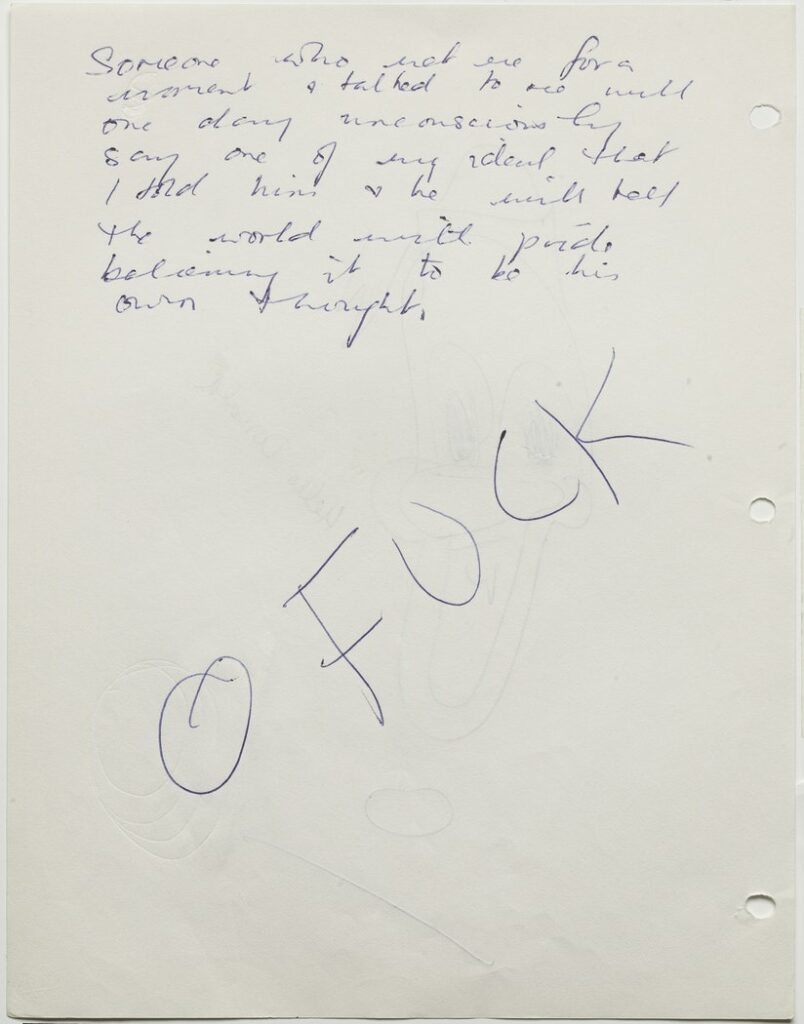

Dance artists are continuously asked to bend and translate their work into a coherent narrative for grants. Writing a future dance with a cold and narrow collection of buzzwords is a considerable amount of work that mostly doesn’t return. What’s more, the application requirements do not alleviate bias, and demonstrate a lack of faith in the medium and the artists that feel at home in this form. Is the lack of clarity mine or yours? It’s like a roommate saying over coffee that you’ve made up the dreams you’ve just told. We learn not to appreciate, and definitely not to openly share, what our amazing unconscious brains conjure in the night. And so there are fewer people who know magic.

Audre Lorde shared in interview with Adrienne Rich the power she perceived from nonverbal communication. She explained that in childhood she had spoken by putting forth full poems she had internalized, poems that held a note of her meaning and essential truth. A rainbow cast from a prism. “And I remember trying when I was in high school not to think in poems. I saw the way other people thought, and it was an amazement to me—step by step, not in bubbles up from chaos that you had to anchor in words.”3 But what chaos can create! Lorde has distinctly achieved that anchoring, and points sharply to the urgency of that skill for survival, for competing with privilege.

Still, to manage clarity in words is its own privilege in an ageist and ableist world, as many do not have the physical or cognitive capability to write or sound words—though they still must be the authority on how they would like to be received and cared for, in complexity and nuance. Working in care settings and assisting individuals in moments when they would prefer autonomy, it feels apparent whose identity and safety has been overly tested.

Much exists between crisp communication and chaos as well. I think about Miguel Gutierrez quoting Donald McKayle in his writing, “Does Abstraction Belong to White People?” McKayle makes a distinction about his dances conveying humanity, not simply form or design.4 I have, in practicing movement that I think is abstract, made a clearing for something deep to emerge. At times this has been a confrontation of what audiences might be seeing as I dance. Dance has a capacity to illuminate what is not so easily said, with as many, or more, connotations and inflections. And in performance, truth comes palpably when it’s passed from one gut to the next, if there is a listener open and willing to hear you. Once again, I fell into the comforting arms of Dolly Parton after receiving formal feedback from a grant panel that I’d presented myself as a “ditzy blonde.” They heard the joke I was telling, though didn’t think I’d understood myself. Certainly this isn’t the worst insult, by any means, but it edits my humanity, and I’m glad to add my piece (with its white privilege) to those who are calling for future funding panels to listen with a whole lot more of themselves, or stop demanding that individuals cater to the elite and shallow system.

I am not immune to miscommunication. My listening will always need improvement, and many unimportant things prioritize their own attention. I have, unfortunately, caught myself barking that classic parenting phrase, “Use your words,” to my little one, as the grunts and yells of his frustration tip into unassociated anger. Though what I mean is that I want him to calm his nervous system and check in again with his need, desire, and interest. A three-year-old can’t yet internalize that suggestion either, but if I make an effort to sit calmly and listen to my own agitated self, he does too—and then, look at us, both better off.

We wear layers in the winter for good reason: different textures hold and release heat differently; we’ve got a system of options within which we can then adjust spontaneously. I run cold, I bundle up, and I feel aligned with physical language, but I’m ready for the beach when the time comes. Years back, I shoved myself into the haunted house of writing publicly and have grown significantly because of it, like having to learn a dance sequence on the alternate body side. Or there is the sad choice to luxuriate in the knowledge that you can get where you’re going with only English.

Tori Breen had a show in Minneapolis parks this past, freezing fall that explored the embodiment possible in a state of police abolition. The dancing was lush and peaceful, desirable. Any idea can be a generative seed, whether the grown plant resembles that early object or not. The aboutness of this dance was told in a prefaced speech and in small spoken monologues layering the movement. To say, “I want you to look at this work and think about police abolition.” Or to list “queer” in one’s bio. A disabled person not using the descriptor of “self-advocate,” feeling it redundant and less than empowering. On the other hand, if the information is commonly available, you might forgo the red carpet for the reader. The chef and cookbook author who chooses not to define daal, leaving the work of understanding to those that don’t know. Identity is supported and unsupported through concrete labels. The originator gets to choose what and how; the audience’s work is to listen.

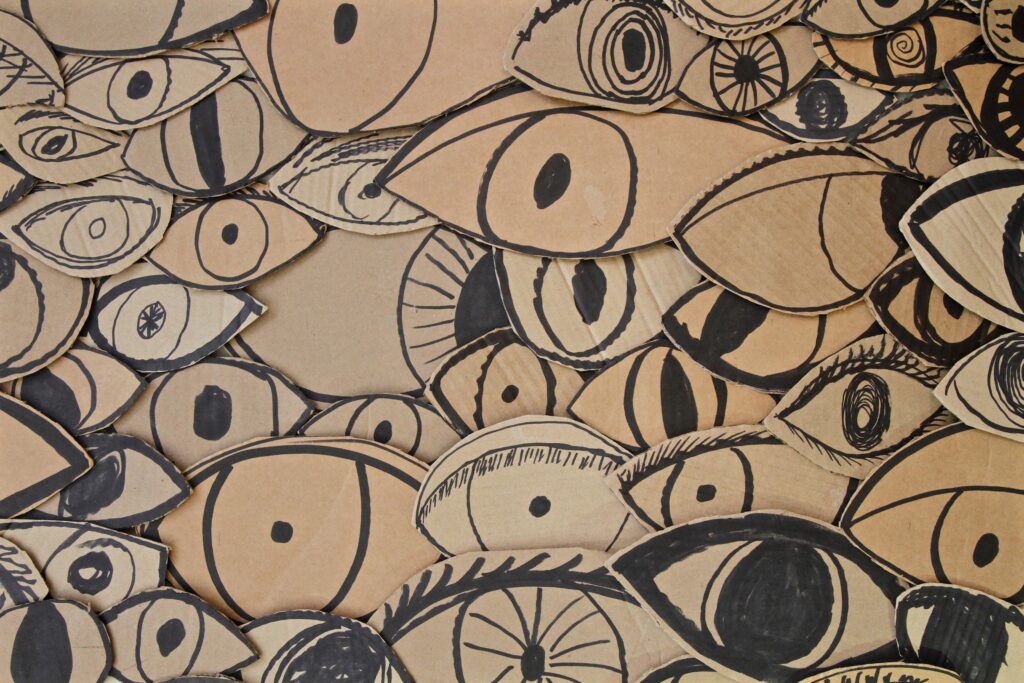

And then there is a response. Frida Kahlo’s paintings offer many “internal parts made visible.” In the introduction to The Diary of Frida Kahlo, Sarah M. Lowe reminds audiences that they are unwanted in the following pages.5 Kahlo’s efforts to obscure her journal writing and automatic drawings by covering initial thoughts with further images and words, using mediums that bleed through the thin pages, make readers’ voyeurism especially gross. She has already given to us her insides, but we dig for more. There is knowledge enough to ponder in the weight of the mark, the color, the images, without heavy-handed and uncomplimentary conjectures which are readily available in the commentary of the Abradale Press translation. Is the intrusion and deprecation justified if we enter curious and admiring? And what if we don’t? Are we looking for proof that she had suffered enough to depict such pain? What if hurt doesn’t come crashing like a bus? What if it comes quietly, like snow, bits accumulating, distinct and hard to describe, overwhelming an entire land at once, making it difficult to see the matter that is still underneath?

I miss art. Art makes opportunity to listen, to understand, to speak, while welcoming that we will never know the whole of it. I’m hoping you are already with me here. So how about a joke? Someone walks into a bar. There are pieces of meat nailed to the ceiling. They ask the bartender, “What’s going on?” The bartender says, “It’s a contest. If you can jump high enough to touch one of them, free drinks for the night.” The person thinks for a minute…