VISUAL ART: An Eden of One’s Own

Art critic Mason Riddle weighs in on a newly published, beautifully rendered book of collages and personal nature journals by Minnesota artist and author David Coggins, EDEN (Cobalt Press, 2008).

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately,

to front only the essential facts of life

..

Henry David Thoreau

THE WORD “WALDEN” EVOKES AN ALMOST HALLOWED SENSE

of place. The idea of removing oneself from the crowd, living in harmony with nature, hearing the quiet, is universally appealing. For Minneapolis artist and writer David Coggins, Pine Lake, Wisconsin is, like Walden Pond, just such a refuge; and Pine Lake’s idyllic environs are the inspiration for his recently published book, Eden: Summer Collages. While Eden is very differenthow could it not be? from Henry David Thoreaus Walden, it springs from the same deep desire of an artist to record the comings and goings of nature in a personal, direct way. Just as Thoreaus Walden chronicles his two years and two months of living, observing and writing in a wild but understated spot, Walden Pond, Coggins Eden charts the artist’s musings and transitions of nature, family and friends for the five months spent at the sylvan Pine Lake, largely removed from the urban garden setting of his Minneapolis home. From May to September 2004, Coggins chronicled his time through collected plant material, found images and bits of ephemera that would construct a narrative of his summer existence, a tale which relies more on image than word, yet reveals a textured story nonetheless.

Pine Lake and its rustic surrounds, the summer escape of his wifes family for nearly a century, have inspired much of Coggins’ artistic practicedrawings, prints and writingover the last decade. Eden, published through the artist’s own Cobalt Press, is his most recent endeavor. Unlike Thoreaus Walden, which constitutes a written act of meditation on nature, Coggins Eden, with its 90 collages, is more a visual rumination, interspersed with only brief bites of text. The book itselfa hardbound, slender tome with a robins egg blue cover backgrounding an image of a languid water lilyconfirms Thoreaus statement How much virtue there is in simply seeing.

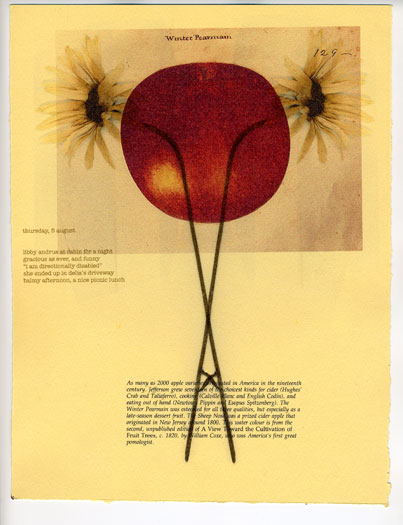

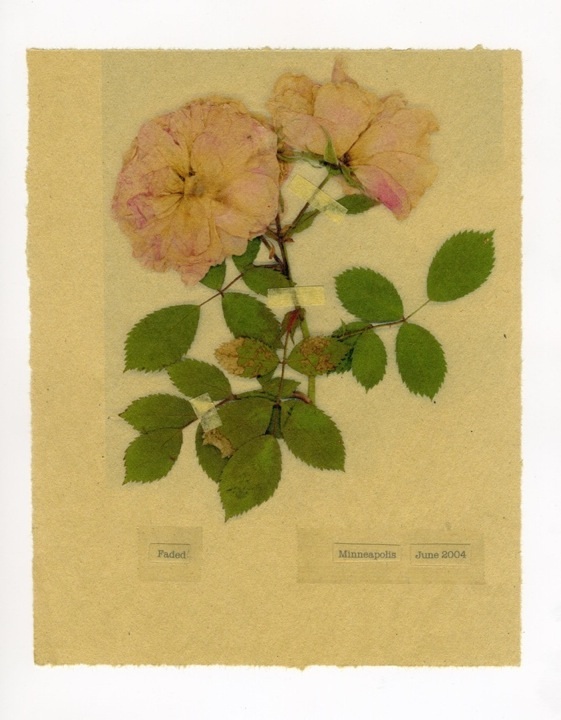

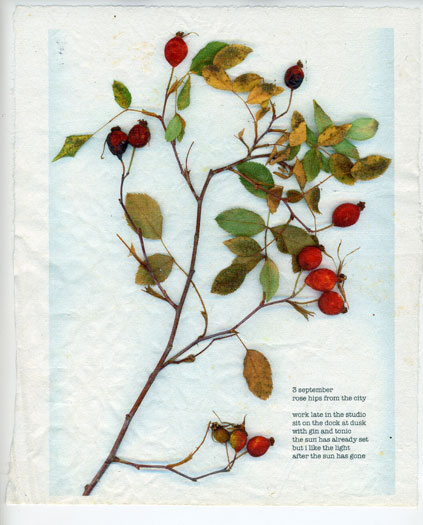

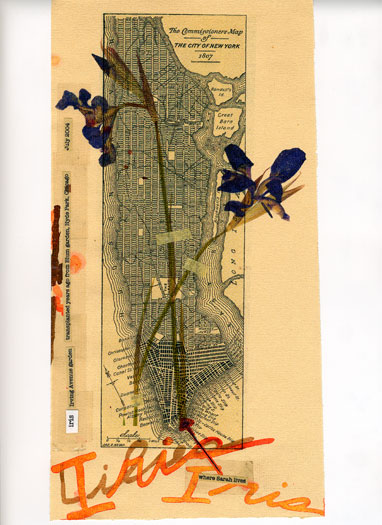

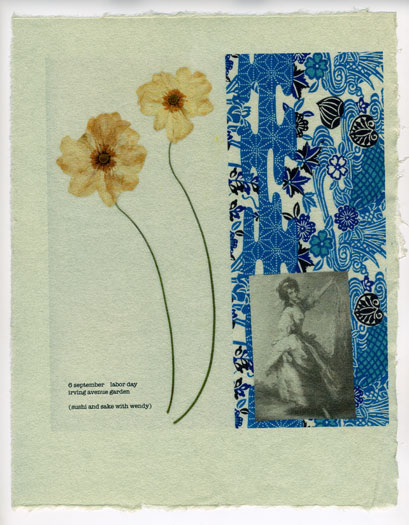

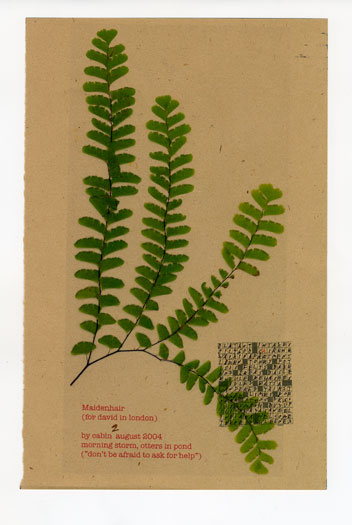

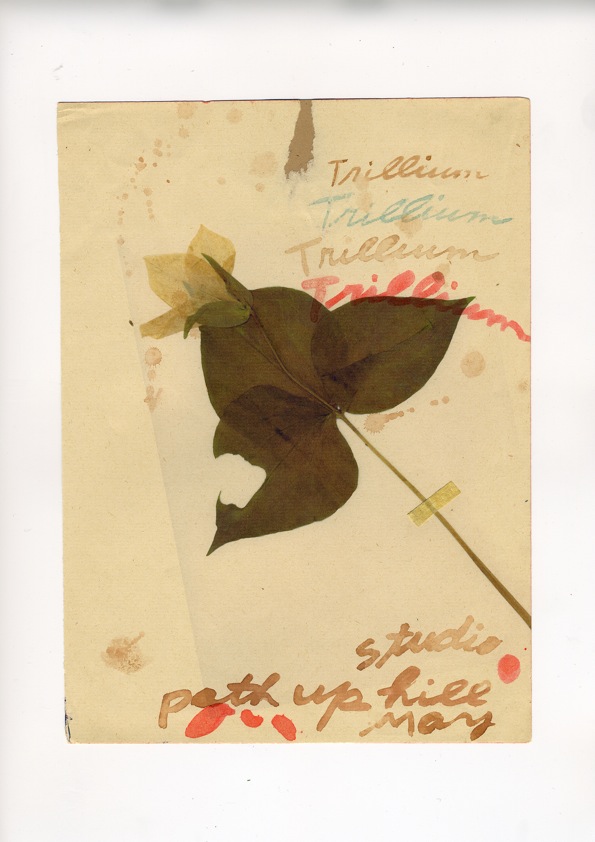

The 90 collages comprising Eden are not collages in the traditional sense: the actual works of art, rather than being multiple layers of materials, images and texture, are a flat, smooth, single sheet of paper that is the result the final print-out – of an additive process entailing multiple scans of raw material. These printed assemblages were then reproduced for Eden.

For each collage, Coggins first collected and pressed flowers, leaves, grasses and weeds from Pine Lake or from his city environment; and then he scanned each dried mass onto paper. In turn, these images were scanned again onto various types of paper, such as sheets of newsprint, hotel stationary, maps, handmade paper, bottle labels or pages torn from old notebooks. Onto these he variously drew other images, penned identifying words or names, scanned additional passages of text, and added a photograph here or piece of decorative paper there. Subsequently, as Coggins assessed an individualized work’s composition, color, and play of information, he might send another piece of paper through the scanner to be imprinted, revealing additional adjustments to visual texture, layers of color, image, memory, and meaning. Although, ultimately, a smooth, unarticulated surface, each collage is an associative archive, a repository of personal ideas and events that date to a specific time and place during the summer of 2004.

_________________________________________________

Each of Coggins’ collages is an associative archive, a repository of personal ideas and events that date to a specific time and place.

_________________________________________________

Coggins structured his book into five chapters, one for each of the five months spent at Pine Lake. Each chapter begins with a single black and white image of a flower or leaf on a blank page. The facing page offers a list of words that serve as titles or written clues to the ensuing collages. The austerity of these black and white pages provides a sharp visual contrast to the colorful and complex collages that follow.

“June” begins with a simple image of a shrub rose. In that month of twelve entries, or collages, one is titled Wines and dated 20 June. Cattails have been scanned onto pale blue stationary from Hotel Peta Palace, Istanbula city Coggins visited more than a decade ago. The text begins, Tonight at dinner with Wendy and David I opened three really good wines, an (old) French Bordeaux, a burgundy, and a California Cabernet and we compared them Scrawled across the page are the words “Plummer Road,” identifying the location where the cattails were harvested.

The 31 July collage, created on an accidental blank page of the New York Times, is dominated by a big yellow sunflower given to Coggins by a Hmong man in the post office parking lot of Bloomer, a nearby Wisconsin town that John Kerry visited earlier in the summer. Other collages reference topical events. One, dated only September 2004, features a dried hydrangea imprinted on a vivid yellow textured paper. The words hydrangea Minneapolis and 1000 dead are printed on the surface. At first the legions of dying autumnal flowers come to mind and then the raw truth sinks in Coggins is referring to American lives lost in Iraq.

Coggins marks moments of his own life: his journey as an artist, as revealed in the scanned image of his Pine Lake studio placed onto one collage, or in an allusion to Winslow Homers woodland studio at Prouts Neck, Maine which is found in another. He pays homage to other artists: Matisse is quoted on the 16 September collage, and on 17 September the artist/writer scanned a yellow daisy onto a reproduction of a print by Albrecht Dürer. Coggins entries also make note of writers such as Jim Harrison and Lawrence Osborne, or other notables like Cole Porter and Thomas Jefferson.

Viewed collectively and perused closely, the book reveals intimate details of Coggins Pine Lake summer the flora and fauna he encountered, the places he traveled, the people with whom he engaged. For much of the time he is alone. Eden is also a poetic look at the passage of time, sometimes bright, sometimes melancholy. Perhaps most provocative is the suggestion that we, the viewers, can never understand the entire story of an experienceeven scrutinized closely, it is a mystery. The text is brief, supplemented by image and material, giving us just enough information to make up the rest for ourselves.

This idea of artists and writers recording the days is not new; the endeavor reaches back long before Thoreaus 1845-1847 retreat at Walden Pond. In early 15th century Flanders, the Limbourg Brothers created the Les Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, a book of hours that depicted not only the calendar, images of planets and so on, but also the daily events of people and their animals. One hundred and fifty years later, Pieter Breugel created a series of paintings late in his life, each representing the daily activities associated with the months of the year. What unites these artists and others with Thoreau and Coggins, and, at the same time, what separates them from archiving endeavors such as John James Audubons Birds of America, is not so much in how they use specific images or words, but in the shared idea of recording their first-hand observations of the natural world as it pertained to the passage of human time. These are time-based, experiential works at their foundation; and the artists who create these sorts of journals, including Coggins, are compelled to record the passage of time through whatever images or words are most revealing of their ideas and experience in the moment.

Eden is a quiet, private associative book that makes the reader a bit of a voyeur. It is beautiful, even seductive, from its birch bark endpapers to the visually compelling collages and the snippets of often-provocative words. As any good art or book should do, Eden causes the reader to think about ones self, ones journey in the larger scheme of things, to assess what has been missed and what yet may be discovered.

About the writer: Mason Riddle is a critic and writer on the arts, architecture, and design. She is the current president of the Visual Arts Critics Union of Minnesota.