Valediction: Charles Biederman, 1906-2004

Charles Biederman, one of Minnesota's most important artists, died December 26. Glenn Gordon gives an account of his life.

All photos by the author. As always, click on image to enlarge.

After a long decline, Charles Biederman, one of the greatest and surely one of the most stubbornly principled Modernist artists, died quietly at home last Sunday afternoon at the age of 98. Entrenched for more than fifty years in an obscure farmstead off a dirt road on the outskirts of Red Wing, Biederman pursued his work with ferociously singleminded conviction. Incapable of compromise, often at the cost of what could easily have been a far more comfortable career, he refused to bend to social norms he considered coercive or to pander to a cosmopolitan art world whose “phonies and hypocrites” he railed at with entertainingly profane vehemence nearly to the end of his days.

Biederman was not one to traffic in small talk. A creator of works of incomparable beauty, he had absolutely no use for the glib irony or the gratuitous ugliness that characterize so much of the art of today. He was an impassioned physicist of the visual, a rigorous poet of the optics of human perception. He conceived of art as an evolving instrument for the revelation of the structure of Nature itself. Irascibly rational and supremely confident of his instincts all at once, he considered himself a conduit for the transmission of the true nature of things, a seer of reality in the lineage of da Vinci, Courbet, Monet, and Cezanne. Every day for many years, until age stole the use of his legs, he would climb the hill behind his house to sit, his feet propped up on a cinder block (which as far as I know is still in exactly the same spot where he left it) to contemplate, like Cezanne before Mt. Sainte-Victoire, the continually unfolding infinitely varied phenomena of nature. He brought what he saw down from that hill like Moses.

Not being a physicist, I won’t venture to pronounce on the scientific truth of Biederman’s claims for his “Structurist” or “Constructionist” art, claims upon which he pontificated at often alienating length in more than a dozen self-published books. All I can do is testify to the effect his art has had on me, from the moment of my first encounter with it in the mid-nineteen-eighties. Drifting through the galleries one afternoon at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, I came across one of his late, cascading wall reliefs–the sudden sight of it fairly nailed my feet to the floor. To this day, in the presence of certain of his later works I still experience a change in the depth and rhythm of my breathing, a clearing of the eye, an involuntary synchronization of my body with the vibrating chromatic and spatial adjacencies solidified in the music of these amazing constructs. Biederman’s reliefs are described academically as intellectually abstracted expressions of nature’s perpetually shifting structural continuum of light and color, which indeed you can say they are, but my own experience of them, and the only one I really care about, is visceral.

My encounter with that wall relief at the M.I.A. was the first of what now feels like a chain of links to Biederman that were pre-ordained. A few years later, I unexpectedly got to know him personally. Toiling as a museum rat at the Weisman (the museum to which he had some years before bequeathed most of his work) I was one of the crew who packed up hundreds of the works he still had in his studio and transported them to museum storage. Not long after this, I left the museum to scrap it out as a freelancer, but I continued visiting Red Wing to photograph Biederman and his surroundings through the last six years of his life. Sad to say, by the time I got to know him he was debilitated from a series of strokes and was now nearly blind, but we were still able, once in a while, to converse over a glass of scotch, sometimes smoking a couple of the vile cigars that–heedless of the ashes burning dozens of holes in his pants–he wouldn’t give up until a year or two before he died.

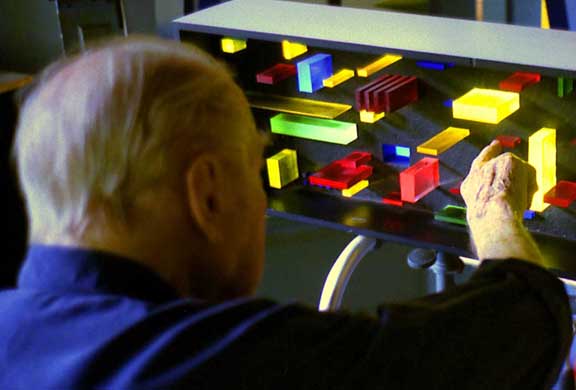

Another artist with a fondness for cheap cigars was my own father, Fred Gordon, who died in 1986. As far as I know, my father and Biederman were unaware of each other’s work, and it’s a damned shame, for they were brothers in the pursuit of what Biederman called the New Art, and would have had a lot to say to each other. Art, however, is miraculous in its capacity to span the gulf that separates the living from the dead, and therefore, about two years ago, while Biederman still possessed the last vestiges of his vision, I brought a work of my father’s down to Red Wing for him to see as best he could. He was barely able to make it out, but was moved by what he was able to see, repeatedly reaching out to touch its colors and feel its forms, my father’s art flowing into his fingertips through a kind of chromatic Braille. After a while, Biederman looked up, distress written over his face, and asked, “Why did I not know of this? why didn’t we ever meet?”

Why? Because the world is made of obscure cul-de-sacs and because the tides of art are unpredictable and history is cruel. If there is any justice in the world, Biederman’s art will escape oblivion, its beauty allowed to wash over us, his work honored with the receptivity that it deserves. Charles Biederman was a prodigious creator, preternaturally sensitized to the phenomenal world. Toward the end, he kept a block-lettered card on his desk that read, “At last I am one with nature.” Renouncing everything but art itself, he now joins the company of the masters he so revered.