Truth Stranger than Fiction: Interview with Marie Williams

Valerie Valentine has interviewed Marie Williams--a quirky voice with an unusual method of publishing. Read her interview, and an excerpt from Williams' new book, here.

Marie Sheppard Williams breaks through the icy “Minnesota Nice” to a warm place of fearless humanity. Her first book from Coffee House Press, The Worldwide Church of the Handicapped is a hilarious and irreverent take on the social work field. Williams was a social worker for many years.

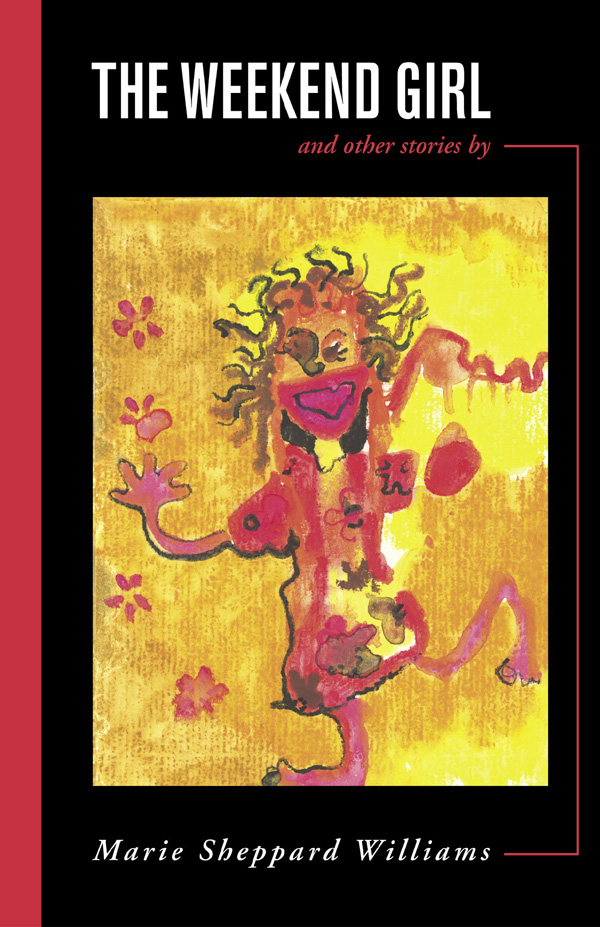

In another intimate portrait, her most recent book “The Weekend Girl,” published by Folio Bookworks, looks at details of her own life. A deceptively simple style links unexpected elements with wry humor. The pacing is deliberate and thoughtful. Simple repetition is used often: “It’s a big secret: we are going to die. No one tells that secret. No one speaks of it.” (“The Italian Story”).

Williams continues to publish in literary journals, most recently Tiferet: A Journal of Spiritual Literature. What follows in an interview conducted by Valerie Valentine, including comments from writing friend Donna Jansen.

Marie Williams: I was born here in Minneapolis, in 1931. I lived here my whole life, except for twelve years in New Ulm at the Flandrau State Park Group Camp, where my husband and I were caretakers. Our daughter Megan, now an architect practicing in London, was born while we were in New Ulm.

Valerie Valentine: So when did you start writing?

MW: I started telling myself stories when I was six, and I started writing things down when I was twelve. But I didn’t try to publish anything until I was fifty years old. I simply didn’t have what it took to publish. Those are two entirely different talents there – writing and getting published.

I was working for the Minneapolis Society for the Blind at that time, and I read my first stories aloud to my coworkers and to blind clients. They all loved the stories. I thought they were good, too; they were different from anything I had written up to that time.

A woman who is still a friend of mine, Esta Seaton, my freshman English teacher at the University of Minnesota, told me, “Even if you don’t write, you won’t lose the gift. If you begin again, you will be a better writer than you are now, because of all the experiences you will have gathered.” She was right.

VV: You were a writer in college?

MW: A little. I was writing real straightforward stories, conventional stuff.

VV: Tell me about the “fictoir” style you created.

MW: It’s a method of storytelling in which I tell what really happened, but I use the techniques of fiction writing to present it. Very seldom do I actually make anything up. I honestly don’t know how.

VV: Truth is stranger than fiction?

MW: Exactly. And it’s hard to get that across when you’ve got a story that’s really true. It’s hard to make people believe you.

VV: Did you change names?

MW: Oh yes. But always, the descriptions of the people are real.

VV: Worldwide Church of the Handicapped was done by Coffee House Press. The second was self-published?

MW: Essentially, yes. I published it with a woman, Liz Tufte, at Folio Bookworks. Liz normally just designs the book and oversees the printing and things like that. But this time, she really liked the book, and she decided to try to act as publisher. It came out about like this: she paid for half and I paid for half.

VV: Why did you choose self-publishing?

MW: Basically because I am psychologically incapable of doing the things that publishers demand nowadays: readings, book tours, whatever. I’m a writer, not a promoter. Again – two very different talents.

VV: How did you like the experience of self-publishing?

MW: It was a pretty good experience. Better than the alternative, anyway. Liz was someone I knew and respected. She designs really beautiful books. And she was willing to let me do things on my own timeline, and on my own terms. “How much revision do you want?” she asked, and I said, “None.” So it’s published exactly as written. Some other editors in the past wanted to rewrite. How could I let them do that? I know what I’m doing, totally.

I was very lucky, because I had two editors who really liked my work. One was Fred Smock, at that time the editor of The American Voice, and the other was Ronald Spatz at the Alaska Quarterly Review. Ron will be publishing another of my stories soon. Either people like what I do or else they don’t. No halfway about it. Either readers understand that my writing is deliberate and conscious, or they think I make really dumb mistakes. For example, they either believe that I intend my punctuation to be the way it is, or they think I don’t know any better. It’s odd, unusual, but it is my way, and it is very deliberate. The method is very conscious. I stole it from my ex-husband. A really great punctuation scheme, I think.

One thing that puts editors off is the way I talk to my readers, the asides. Asides are what I do, that’s the way I write. People who like it, like it a lot. It reads like I’m sitting here talking to you. I think it works fine; some editors think that it means I don’t know how to write a story. Well, it comes across as scatterbrained, one thing leading to another. But everything comes together at the end. I rely very much on my style, to entice people to make it to the end . . .

Donna Jansen: Memoir has become such a big thing now. But memoir is not what Marie does when she talks to the reader. Memoir is a sort of one-woman show, exposing a life. But what Marie does is very different, the voice she has is conversational, and you feel this bonding with author. When she says, “You want to hang in with me?” or, “I’m very interested in what you think about that.” It’s conspiratorial; the author and the reader are in it together.

MW: Not everybody understands how conscious or deliberate that is. The part in “Church” where I write, “Please like me. I don’t care if you like me or not, but hey, please like me.” What that was to me was a little allegory for the relationship between the writer and the reader, because the writer can’t exist without the reader; but he wants to pretend that he can, all the time. He wants to pretend that he’s writing for himself; but without the reader, there’s nothing.

VV: Do you have a writing partner or friend who you show things to?

MW: This woman, Donna Jansen.

DJ: We have a great time. Mostly, Marie reads her stories to me as they are being written. It’s not often that I make comments. Sometimes I’ll take about an ending: it works for me, it doesn’t. . . .

M: And sometimes I take her advice and sometimes I don’t. I almost never take other people’s advice.

VV: What writers have influenced you?

MW: Tolstoi, in the short stories. Sherwood Anderson. Saroyan. Kurt Vonnegut. Borges. Broges was a poet, then one day he fell and injured his head, and when he woke up he was a story-writer, just like that. That gave me the idea that you can do anything, that anything can happen in the world. I decided one day that I was not going to be a cynic anymore. That continues to be important to me. I can be as nasty as the next person, but I try to curb it.

VV: I noticed that one of your blurbs in by Howard Zinn. Do you know him?

MW: Howard Zinn and my friend Esta Seaton taught together at Spelman College in Atlanta. I’m working on a story right now called “Howard Zinn and the Umbrella.”

VV: Do you do other kinds of art?

MW: I do watercolors, pencil drawings, pastels, some collage. I write poetry when I feel like the prose writing is going stale. A class in experimental poetry blew my head open, like a breath of air. Art and poetry prepare me for going back to brose writing.

VV: How do your friends and family react to you writing about them?

MW: My coworkers enjoyed it. Friends ditto. And the people in my family have been very supportive. But there’s one branch of my family I did not tell about The Weekend Girl. I actually called one of my cousins “just this side of retarded.” The next book is absolutely going to blow the lid off. It’s about my family and how we grew up. There’s plenty of stuff in there that’s going to just offend everybody. I think it was Joan Didion who said, “If a writer has got any family and friends still speaking to her, it means she hasn’t told the truth yet.”

VV: How would you characterize your writing?

MW: Um. Unusual. Odd. Different. Easy to read. Funny. Anne Lamott once said that I was the funniest woman in Minneapolis.

VV: What’s your advice to young writers?

MW: Setting up a support system is vital. If you know you’re good, don’t solicit or accept criticism. Esta told me a thing once that she heard from a guy who wrote for the New Yorker: “If there’s something that every editor hates about your writing, hang on to that, because it’s what makes you different.” And people always tell you to start small. Build a resume. Hey, no. If you know you’re good, aim high. I knew I was good, and my first publication was in the Yale Review.

Curious about Williams’ quirky style? Here’s an excerpt from “The Weekend Girl.”

My Aunt Anna identifies with me. She thinks that we both have had tragic lives. I deny a parallel. I can’t give her that. Good God, it would destroy me. I am for Christ’s sake sorry enough for myself already.

I go to visit her with my mother maybe three times a year. We live in the same city, but on opposite ends of it. I am very busy, I work hard, I work as a social worker, it is a tough job, it takes all my energy. I help my mother a lot, take her shopping and what-have-you. This is where my duty lies. I don’t see Aunt Anna very often.

Well, damn it, she upsets me. I don’t need it. I can’t do anything for her; it makes me frantic with helplessness. What could I do for her? Shoot her?

When my daughter, sixteen years old, decided to go and live with her father, my divorced husband, in California, Aunt Anna was all mourning and sympathy.

You miss her, Joan, don’t you? she said. You miss her terribly.

No, I said: Would I miss a toothache? That child made my life utter hell for a year before she left.

But your daughter, she said. I know you miss her.

I do not miss her, I said firmly. I caught my cousin Cyril’s eye across the room; he and I often have extraordinary moments of hilarious contact. I have never known Cyril well at all in the way one usually knows people; he doesn’t talk much; never did; but I know him, do you understand? We are in agreement about his mother. We think she is absolutely an old horror and crock; we are both crazy about her; our shared view of her is a total warm tie between us. We look whole conversations at each other.

– What can you do?

Shrug. Lifted eyebrow. Silent laughter.

– Nothing. There is nothing to do.

– Humor her?

– Punch her in the nose.

– Love her? Love a porcupine.

– Jesus Christ, is there any answer?

Grin.

– God, isn’t she funny? Isn’t she great? Isn’t she awful?

What can you do?

Joan, you have had a tragic life, my Aunt Anna persists. Just like mine. You lost everything you loved. You lost your first little son. You loved your husband and you lost him. And now you have lost your daughter, your darling little daughter . . .

Lies! my heart screams.

I feel really pissed, really angry. No, I say, loud; this I want her to hear for sure: I have not had a tragic life, Aunt Anna. I have had a good life, an interesting life. My marriage was very good for a long time. When it wasn’t good any more, I ended it. I did a good job bringing up my daughter, and when she was ready to go, I let her go. I feel good about it. I have a good life. No, no, she says, nods, grimaces, twists her hands in an agony of sympathy I do not want. I know, she says, that you have had a sad life.

Jesus god. I don’t want this. I don’t need this. I hustle my mother into her coat. I say goodbye to Aunt Anna, kiss that soft old eager avid cheek. I go. I have a feeling of abandoning my cousin Cyril to a desolation beyond telling.

My daughter Margaret, when she comes to visit, won’t go with me to see Aunt Anna. It’s too sad, she says. It’s too terrible. It makes me feel like I am going to die some day.

“Weekend Girl” is available from Folio Bookworks,

3241 Columbus Ave.

Mpls, MN 55407

(ph) 612-827-2552

(f) 612-827-4417

Price: $15.95