Trialogue: Thomas O’Sullivan on Cy Thao

Thomas O'Sullivan did a Trialogue talk at the Minneapolis Institute of Art on the work of Cy Thao, a series of 50 paintings that tell the story of the Hmong migrations.

Trialogues are discussions of the current MAEP (Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program) show at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts among a critic, an artist, and the audience, sponsored by VACUM (the Visual Arts Critics’ Union of Minnesota). On June 27, curator and critic Thomas O’Sullivan held forth on the works of Cy Thao, and lively conversation ensued. What follows is the text of O’Sullivan’s introduction of Cy Thao and his work, and a Postscript that gives some sense of peoples’ response.

This is an extraordinary moment in American and Hmong cultural history: Minnesota’s major museum is hosting two events for two exhibitions. One is the opening of “Currents of Change,” a curatorial celebration of an 1850s steamboat junket in the decade that the state of Minnesota came into existence, seen through high-style antiques and paintings. The other event is this Trialogue, a public conversation with an artist who didn’t wait for the curators and museums to re-create his people’s story, but committed himself to tell it from the inside. History through art is in the air today.

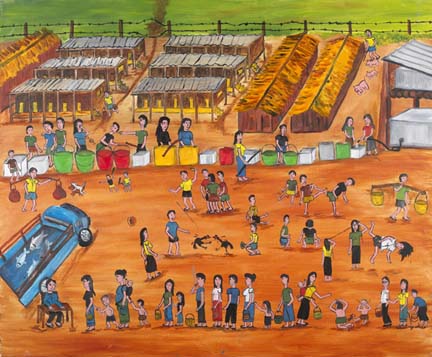

Cy Thao was born in 1972 in Laos where his father was a provincial governor who fought with the CIA in the so-called “secret war” within the Vietnam War. When the United States left Vietnam in 1975 Cy’s family crossed the Mekong River into Thailand. In Cy’s own words, “My family spent the first two years of my life trying to escape the war and the next five starving in a refugee camp in Thailand.” They came to St. Paul in 1980, in the first wave of a migration that has altered so many aspects of social and cultural life in the Twin Cities: a journey that led from the agrarian highlands and rivers of southeast Asia to this multi-cultured, high-tech city in the snow belt.

Cy attended public schools here: he went to North High School in Minneapolis for three years as his parents worked multiple jobs and saved money to buy a home for their family of eight children in Brooklyn Park. Cy graduated from Park Center High School there. The Thao family version of the American dream progressed: his parents moved to the suburbs in Blaine, and Cy went to college at the University of Minnesota-Morris, out on the prairies.

I found his description of his art studies at Morris to be especially revealing, of the man as well as the artist. As a freshman Cy talked his way into John Stuart Ingle’s class, and Mr. Ingle became an important teacher and mentor. It speaks well of both student and teacher that Cy’s body of work here is in many ways the exact opposite of Mr. Ingle’s. The typical John Stuart Ingle painting is a large, cool, exquisitely detailed watercolor, a still life or interior view of fruits and silver and fine old furniture. But Mr. Ingle, Cy says, “allowed me to find my own style and make it better.” Cy also speaks of Jenny Onofrio at Morris as a key teacher who helped him develop a firm grounding in the fundamentals of painting by setting up special projects, arranging drawing sessions for him, and so on. In other words, Cy learned from these two artists at Morris all the art-school technique that he would make himself abandon as he took on his first major project, “The Hmong Migration.”

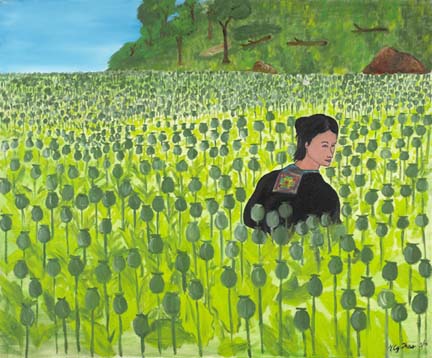

Cy graduated from Morris in 1995, with a double major in studio art and political science. In his junior year he had begun his series of paintings of the Hmong peoples’ story and for it, he says, “I let everything I know about art go. That was the hardest part.” He adopted the pictorial strategies of Hmong story cloths, the appliquéd needlework pictures made by Hmong women in the refugee camps to record their experiences and to earn some money for their families. As Cy puts it, “These were like picture books without words.” Think of what that technique imposes on the artist: a reliance on flat, strongly-contoured, single-color shapes arrayed across a two-dimensional ground; an approach that invites plays of scale and circular narrative, but offers little in the way of atmospheric or linear perspective. Visually they have more in common with the childhood drawings Cy and his brother made than with the art-school techniques he’d been mastering.

When I asked Cy about his other work, he said “If you look at my portraits and my still life paintings, and at my Migration series, you can’t tell it’s the same artist.” Those other works are illusionistic in space and modeling and coloration; he describes them as “technical, realistic, boring” but notes that they do sell readily. I think that makes Cy’s commitment to adopting the Hmong story cloth’s pictorial language, with its apparently artless mode of representation, all the more courageous, for he’s accepting the risk of viewers and critics assuming he lacks the skills or training of the so-called “fine artist” in the Western tradition.

That tradition of modernism turned to distinctly American ends also has an important place in Cy’s vision. Cy points to favorite and influential masters: Van Gogh, for one, and Max Beckmann, whom he calls “comical”—that opinion alone qualifies Cy as a dyed-in-the-wool expressionist, in my book. But the key historical artist for the “Hmong Migration” series is Jacob Lawrence, the African-American painter and printmaker who also worked in series of historical themes, with written descriptions that make the works both verbally and visually informative. Cy saw an exhibit here at the Institute of Lawrence’s “Migration of the Negro” and “Life of Harriet Tubman” series. This confirmed Cy’s own use of a distilled, shape-and-color-based narrative style accompanied by his written commentaries, a strategy Mr. Ingle had also recommended to him.

Cy completed his project in about six years’ time: “The fifty pieces are just one big piece,” he says, an epic painting that spans six thousand years of Hmong history from China to Minneapolis. He first showed it in a tent in a University Avenue parking lot, the ultimate alternative community space, and recalls that “A lot of people saw it once and came back with their children or parents so they could talk about these things. The older people, the people who were old enough to remember, they would look at a painting and say ‘Oh, that’s just how it was.’ That made me feel pretty good, that I got it right.”

I think he also got it right for viewers like myself for whom the Hmong people are neighbors whose history is a hazily-understood fable of oppressed people persisting across time and space and somehow ending up here, their kids and mine sitting side by side in city schools. Cy’s telling of a heart-breaking, violent, ongoing struggle for a dignified life, using the most elementary of storybook styles, somehow makes the enormity of Hmong survival more compelling, at gut level, than history books and photographs can.

I think it’s all the more important as an artwork because the story continues: this year about 5,000 more Hmong people will leave refugee camps for Minnesota, where they too will find welcomes and racism, opportunities and rejections. But they will be the first arriving immigrant group to find their own story in an art museum, told by one who shared their experiences.

Postscript: The Discussion

Cy Thao’s comments in the Trialogue offered insights into an artist who has, of necessity, lived and worked across the borders of several spheres: Hmong and American, painter and politician, academically trained realist working in a consciously naïve style.

Cy is an elected member (DFL) of the Minnesota House of Representatives for District 65A, centered on St. Paul’s demographically diverse Frogtown neighborhood. He spoke of the need to act from different stances in these roles: he finds it necessary to constrain his personal opinions when speaking and acting for his constituents, while his instinct and agenda as an artist is to express his own feelings with passion and conviction. He cited his experience as a Hmong immigrant in the public schools as a preparation for this professional role-splitting: as a young man he was the “good Hmong boy” at home, while the racism and bullying he encountered at school demanded he be a fighter as well as a student.

Cy’s decision to paint the “Hmong Migration” paintings in a simplified style based on story cloths has, he’s found, led to his being typecast in that mode: viewers expect him to work only in that style. But his education predisposed him to a more academic realist style, he noted, and when he finished the Migration paintings, he returned to realist still-life painting as a release from the concentrated effort of painting in the story-cloth mode.

For his next major project, Cy will produce a series of paintings of American history as one Hmong-American immigrant sees it (as opposed to the textbook version). He plans to do this series in the story-cloth-derived style as well.

In discussing the prospects for Hmong participation in the visual arts, Cy seemed to downplay that aspect of Hmong life as secondary to the process of getting an education, jobs, and a firm family footing: the classic American dream of immigrant success. One audience member, however, noted a recent Intermedia exhibit of Hmong artists, including a sampling from Cy’s series. And in response to a question about how his art and life may have been different had he not come to America, Cy gestured at his series of fifty paintings and said, “In Laos, if I had this much ambition, I’d be dead.”