Torches, Periscopes, Merwyns: New Public Art in Minneapolis

Minneapolis's public art program is commissioning and installing works regularly around the city. Here's an account of five Neighborhood Gateway projects new this year.

Five public art projects funded by the city of Minneapolis will be dedicated this summer and fall, as part of the city’s Art in Public Places, a regular part of the City’s Capital Improvement program since 1992. The program commissions new artworks, conserves and maintains existing works, and provides support on special projects to other City departments and boards.

Like many others across the country, it’s funded by the city’s pledge that one percent of the construction budget for any new public building is set aside for the purchase or commissioning of artwork. The percent program is part of the Division of Cultural Affairs of Minneapolis Community Planning and Economic Development Department and the Minneapolis Arts Commission.

These kinds of percent-for-art programs emerged in the United States in the 1960’s and ‘70’s as a way to democratize the experience of art. It might be fair to say that in the early years of public art projects, artwork was often met with hostility or confusion on the part of the audience it was intended to address. In the long history of these kinds of projects, a collaborative model has gradually emerged as artists and arts administrators have developed ways of creating public artwork by bringing artists, architects, community organizations and others together earlier in the course of the project—getting the art design in on the ground floor, so to speak.

In Minneapolis, for example, Neighborhood Gateways were the original focus of Art in Public Places. From 1992-1999 the program offered communities the opportunity to sponsor public art works. Mary Altman, public arts administrator, says neighborhood steering committees have been active partners with the City in choosing locations and projects that have a deep significance in their community.

The City of Minneapolis has contributed about $50,000 per project, leveraging considerable levels of funding from neighborhood organizations. A total of 13 gateways have been dedicated to date, with several reaching completion this summer in three Minneapolis neighborhoods; Marcy Holmes, Seward and Hawthorne.

Artists for potential projects are chosen based on qualifications and are asked to submit proposals for consideration by a volunteer advisory panel. “Today’s public artist typically designs and executes works of art under a committee system,” says artist Andrea Myklebust, who is completing work on a gateway project for West River Commons on Lake Street and West River Road.

“Selection panels are compromised of voting members who usually include representatives of the owner, eventual occupants or users of the project, non-arts members of the larger community, and an arts professional.”

“This democratic arrangement for the commissioning of pubic artwork is a natural evolution of the process by which these projects are funded,” Myklebust says, “and provides a level of oversight which has been important,” she added.

There are several challenges in selecting project sites, says Altman. The best public spaces respond to the needs of the people to which they belong, ideally provide visibility to a neighborhood, and also help to create functional, lively and vital spaces.

Myklebust says the best public and civic artwork forges strong connections between people and their physical environment. “I think artists can take wordless dreams people have about the place, the future and put them into a visual object which they can look at, encouraging a larger conversation” to start taking place in the community. “I’d like to think the artwork will get people to start asking questions like ‘What do we value?’ ‘How do we live in community?’”

The artwork Myklebust has created for the gateway at West River Commons, includes a 22-foot sculpture of a torch with a 7-foot gilded flame. The sculpture is the central element in the piece, which also includes stonework and limestone benches that are integrated into the site’s public plaza and landscaping. Myklebust worked in close collaboration with landscape architect Andrew Caddock to create the environment.

Partners in the West River Commons project included the developer the Lander Group and the Longfellow Community Council.

While public art projects are not “pure collaborations” in the sense that ultimately, not everyone can have the final say on design, the process is more community-based in the sense that the artist typically spends a lot of time during the design process inviting community participation. For Myklebust, this process first involves some basic research on the neighborhood or community where she has been commissioned to create an artwork. This research, which can be both formal and informal, Myklebust says is one of the most interesting aspects of the process involved in public art projects.

Aldo Moroni similarly says that getting to know the neighborhood involved in a public art project is important because the artwork “should really reflect the character of the people and place.” His goal for his “Sixth Avenue Stroll” at the Marcy Holmes Gateway was to create a visual entrance to the neighborhood that was playful, intentional, and handmade. A series of 26 columns topped with bronze models of historic neighborhood buildings on 6th Ave between University Ave. and Main Street, “Sixth Avenue Stroll”

brings a spirit of history and delight to what Moroni calls “the first neighborhood of Minneapolis.”

The models Moroni created are interpretations–not necessarily architecturally accurate. But they do represent each building with some degree of accuracy. Research for each piece began with photographs, Moroni says, but three-dimensional buildings were created on-site from the back of his van-turned-studio in a process he describes as “on-street carving” from stoneware clay.

The models, eventually cast in bronze, attempt to capture the character and feeling of each building, Moroni says, so the ability to work in the presence of the building is very important to the process.

Moroni, an artist who has a long history with public arts projects, worked in collaboration with the neighborhood and historian Penny Peterson on the project, which he describes as “intense and emotionally charged.” Not only was the project physically exhausting (down the last detail of the house-shaped cookies he was baking for the dedication ceremony), but also very emotional for Moroni because of his long history with the neighborhood, dating back to 1977, when he participated in an artist’s residency at Marcy Holmes school.

Partners in the project included the Marcy Holmes Neighborhood Revitalization Project and Minneapolis Public Works.

“I feel emotionally tied to the neighborhood,” he said, “and in a way, that made the project very important to me. I am trying to get a sense of the people and place,” Moroni said, “I am interested in democracy in the arts and my idea is to create something that has personal meaning to the people who live in this neighborhood.”

Seward Gateway artist Majorie Pitz also speaks about the importance of creating a project that is meaningful to its neighborhood and surrounding environment. “My whole practice has always been focused on spaces that are used by the public,” she says, “so that has really influenced my work.”

Trained primarily as a landscape architect, Pitz created the “Merwyn” at the center of Triangle Park (on the corner of 26th Ave. S. and Franklin Ave. E)as her first sculpture. She wanted it “to engage children’s imaginations.” Partners in the project included the Seward Towers Corporation and the Seward Neighborhood Group.

Because Triangle Park is privately owned by Seward Towers, it was an unusual site to be chosen for a public arts project and made the collaborative process between Pitz and her partners challenging, but “exciting and dynamic.” Members of the Seward Neighborhood group wanted the park to be redesigned to integrate the sculpture into its overall environment, but initially there were no funds identified to renovate the park.

Although this presented a challenge to the project, Pitz said she was impressed by the community’s commitment to integrate the artwork into the overall vision. “The whole idea of a neighborhood interested in the integration made it an ideal situation to be in as an artist.”

Constructed from concrete and larger than life, her “Merwyn”, a brightly colored creature seemingly erupting from the ground, is now one of the central focal points of the park, which is still under re-design and construction.

The Hawthorne Gateway in Fairview Park (26th Ave. N and Lyndale Ave N.) designed by artists Norman Andersen and Kathy Schaefer, in the final stage of installation, is a large steel tower construction with periscope views, reminiscent of Fairview Parks’ original standing tower. The tower, made of sandstone, served as a lookout point for the park and was torn down in the mid-1960s.

The gateway designed by Andersen and Schaefer is a 22-foot brick-red tower with large gothic arches at its base, which house periscope viewers that are sited for views of the neighborhood and the skyline of Minneapolis. Schaefer, an art historian, said that she and Anderson did a lot of research on the neighborhood in advance of the design and were interested in using elements in the piece which were important to the history of the neighborhood. “It was an exciting part of the process,” Schaefer said, “uncovering stories, getting to know people in the neighborhood, including a woman who is more or less the neighborhood historian, and then trying to create a form which would represent the character of the place and the people living there.”

Anderson and Schaefer partnered with the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board and neighborhood groups in the Hawthorne neighborhood.

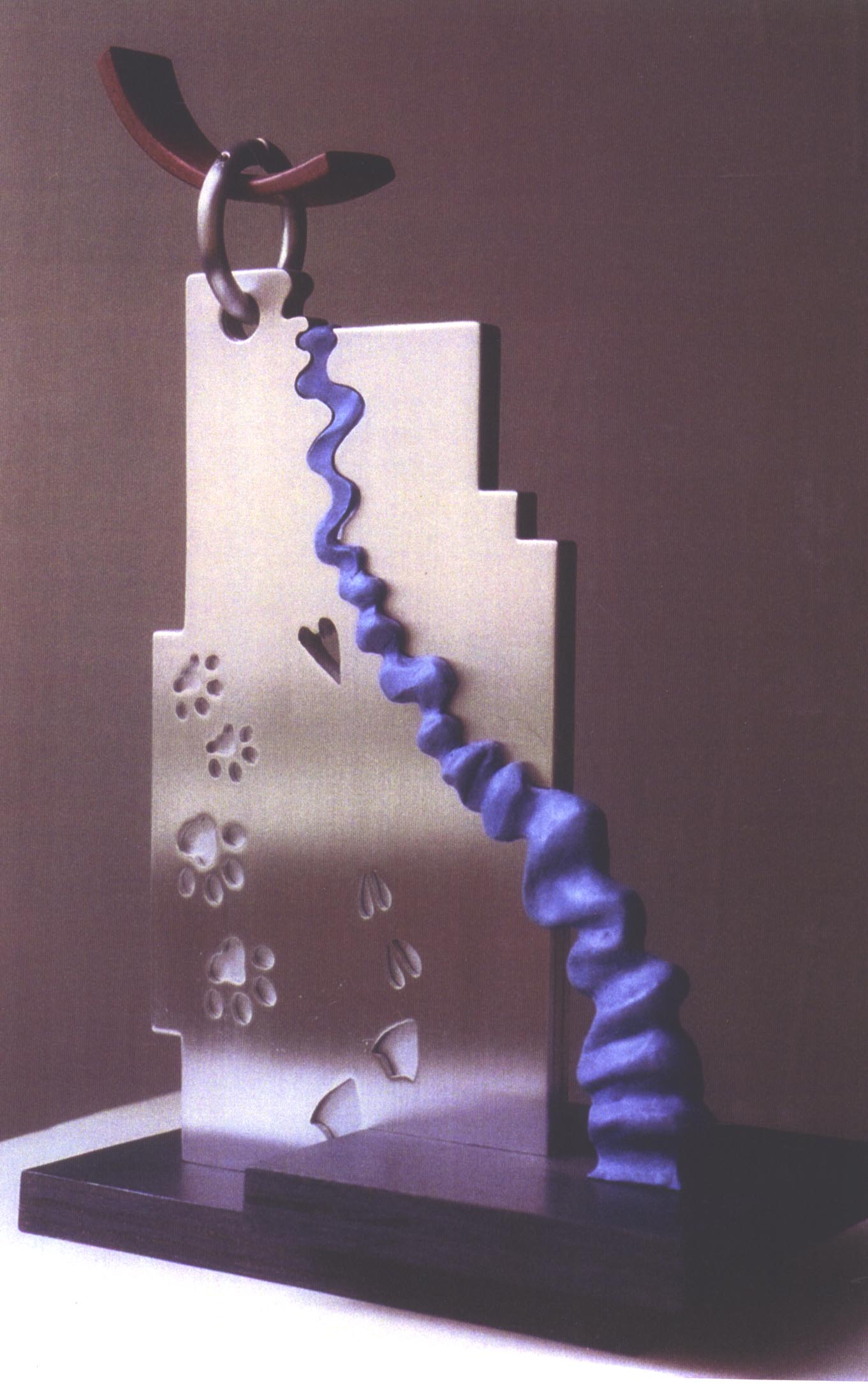

Caprice Glaser’s sculpture outside the entrance of the Animal Control Center (212 17th Ave. N) is a whimsical 13-foot steel structure inspired by the shape of the city and is reminiscent of a city animal I.D. tag.

Glaser, who has a long artistic history working in wood, collaborated on the project with artist Ray Becoskie, who has assisted her with steel fabrication and construction. Partners for the project also included Animal Care and Control and Minneapolis Public Works.

Glaser’s research for the project included a day spent shadowing animal control officers in an animal control van and a full-tour of the animal control facility. “It’s always really important to have enough time before designing the artwork to have enough time to get to talk to people,” she said. She also assembled a neighborhood meeting to solicit feedback on the design.

A veteran of public art work projects, she described the process as “terribly challenging” but invigorating. “I think I come out of a project with a different art brain,” she said, “and I think it feeds into my personal art work.” “I know some artists are frustrated by the process—calling it ‘art by committee,’” she said, “but I find the process really inspiring.” “A luxury,” she said.

You can view and learn more about the work of Norman Andersen, Caprice Glaser, Andrea Myklebust (in collaboration with Stanton Sears) on their home pages at mn.artists.org–see the links below.