to love to work and to be in pain

On disability identity, the labor of artmaking, and the agency of reclamation

I have always been the kid on the sidelines. Monitored and watched closely, encouraged to “take it easy,” or told, “Maybe now is a good time to take a break and use your inhaler.” Even with light physical activity I would be short of breath. When asked about my condition, there were few things that I could say: “I was born premature and they were unsure if my lungs would fully develop,” and, “I have a heart murmur.” For 24 years of life, I had little to no language to describe the things that affected my physical ability and separated me from other children. As a child, it never occurred to me why, but as an adult with my medical treatment in my own hands, the full image is becoming clear.

I always knew that I was born premature, at 32 weeks’ gestation; what I didn’t know, and have recently learned, is that I was born with an atrial septal defect (ASD)—a hole in my heart that doctors assumed would close on its own but never did. When I was able to gain access to my medical records, I found myself flipping through pages of medical information and test results I couldn’t understand. Amidst these pages, a detailed story of the tests and procedures of the first few months of my life unfolded, and gave light to a life of doctor’s visits and extended stays in hospital beds. What these files fail to explain is how I and the people involved were affected; my mother’s constant fear and worry of how to continue day-to-day knowing that her child was sick. To Love Something More Than You Love Yourself explores the complexities of the joyful and emotional realities of being a mother to a sick child. This relationship, as explained to me by my mother, is interpreted through banding and color. The piece moves from a dull banding of pink, green, and yellow to a vibrant and bold purple and blue. The dull colors reference the uncertainty my mother felt as she wondered whether or not she would lose another child. The excitement and chaos of motherhood is symbolized by the purple banding with interruptions of white threads, representing both the joy of becoming a mother again after losing a child and all of the time spent in the hospital. The experience of making this piece was physically demanding; the 20 hours hunched over and under the loom to prepare 480 threads and weave them together was felt throughout my whole body. This is not uncommon for my practice.

In early June of 2020, I sustained a back injury that greatly affected my mobility. Both my primary care physician (PCP) and chiropractor told me they believed the injury was the result of the four years in undergrad that I spent putting extra pressure and strain on my joints for the purpose of artmaking. Part of what I enjoy about weaving, quilting, and printmaking is the labor involved in the process. A bit of pain and recovery time just felt like occupational hazards when I was a student, a part of the give and take of life. The labor-intensive process is also consistent with the charged topics explored in my practice.

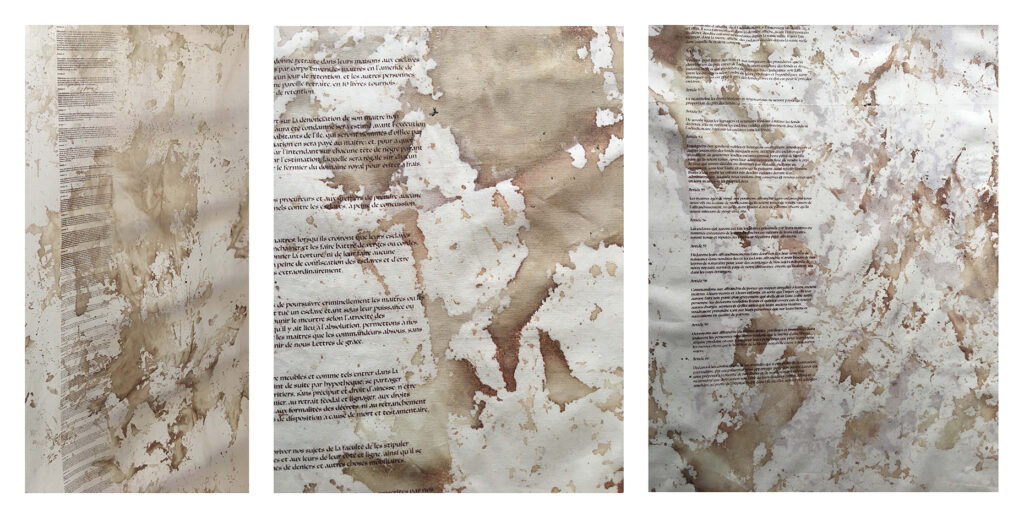

The process of screen printing To Wear the Length of Bloodied Shroud My Ancestors Did Weave, a piece that is 15 feet in total length with over 6 feet of text, was full of excitement, but also presented many physical challenges. Using a screen that is 60 x 40 inches, the piece required two printers to be in perfect sync in order to not shift the print and apply equal pressure the entire length of the screen. In a similar manner, the finishing and staining process required me to be on my knees bent over the side of my bathtub, a rather cold and uncomfortable position to be in. A mixture of cattle, porcine, and chicken blood, the piece required me to set the fibers and stain by boiling and handwashing the piece, a process that felt as natural, domestic, and confrontational as the work itself.

When speaking with my doctors about my injury last June, for the second time in my life it sounded as though doing the thing I loved was destroying my body. The injury, while temporary and made better through regular physical therapy and chiropractor visits, changed my daily life drastically. I had never experienced feeling embarrassment and helplessness from limited mobility in this way, even as a child. The shame and frustration of not being able to stand to wash myself, cook, or work were exacerbated by the felt, but not said, questions like, “Well, how hurt are you?” communicated through glares and glances at work. As a result of my back injury, I became unable to stand for the entirety of my shift, and asked for a chair. I discovered this request for accommodation needed to be made formally by my PCP. I felt low and vulnerable. Why did I need a third party to validate what I was experiencing within my own body?

As a child, I didn’t recognize that part of why I was closely monitored and felt separated from other children was because of my disability. I wasn’t given the opportunity to recognize my need for glasses, my stutter, or cardiovascular problems as a disability, because I had been shown a very narrow definition of disability. It wasn’t a negative one; I was always taught that having a disability did not mean your life couldn’t be as fulfilling as anyone else’s. I watched my cousin, who has cerebral palsy, do everything she wanted. She was a model of “overcoming adversity.” Her disability was visible in ways my own weren’t to me, not yet. She was my example of what it meant to be a “Good Cripple,” as described by S.E. Smith in “The Transcontinental Disability Choir: Disability Archetypes: The Good Cripple.” Smith writes,

“The Good Cripple is the safe, comfortable depiction of disability. […] They are quiet, and patient.[…] They never complain. Not about pain, not about lack of accessibility, not about the piles of medication they take every day, not about anything. […] The Good Cripple will do well in spite of disability, the disability is an obstacle to be overcome […]”1

With my back injury and the presence of a global pandemic, the past year has expanded what I consider to fall under the umbrella of disability, and has revealed which of my disabilities are “visible” versus “invisible.” I want to understand why it has taken this long for me to expand my definition of disability, and why it felt so natural to recognize my cousin’s disability but not my own. Had I not been disabled “enough”?

The hierarchy of disability is the belief that some disabled people are more acceptable and “less disabled” than others in our culture, and stems from disabled and non-disabled people alike wanting to distance themselves from the negative tropes assigned to disabled people. Certain language used to describe people with disabilities maintains this hierarchy and separation; for example, when a person uses a mobility aid and they (or others) insist that “their mind is fine.” This separation is also presented through labeling autistic people as “high” or “low” functioning. These excuses—“I’m disabled in this way, but not that way”—imply that certain disabilities are worse, that disability is a negative trait, and that people with disabilities must compensate in some way.

Common models of disability serve to reify the disability hierarchy and further contribute to rampant ableist attitudes and behaviors. Ableism categorizes people with physical disabilities as more disabled than people with invisible disabilities, and those with more significant cognitive impairments above others. People assume that some people with disabilities “suffer” more or “have it worse” than others. For decades, people who work for accessibility for disabled persons have been slow to acknowledge the nuances of the disability hierarchy by employing charity, medical, and social models to assess attitudes towards disability. The charity model describes and interprets disability as a tragedy to be mitigated or removed by generous giving;2 the medical model identifies disability as an individual defect to be eliminated or cured;3 and the social model asserts that disability arises because society is not shaped to include people with impairments and provide them with the opportunity to choose their own futures.4 Ultimately, these models echo the separation and categorization of disabled people, which contributes to the continued subjugation and neglect of disabled persons around the world.

Access to my medical records, as well as language to explain what is happening with my body, have created a more embodied identity as a disabled person, but certainly not without fear or concern. The benefits of modern medicine seem so obvious, but even so, medicine is based around a crisis intervention model that has pathology as its focus, and by extension, processes of defining and classifying pathologies similar to many systems of oppression. These processes are an expression of power, as professionals use their knowledge to create security, normalize conditions, and influence their patients, who are depersonalized and disembodied in the process.5 But with a new diagnosis, or knowledge of diagnosis, here is a whole new host of problems created. Though some find freedom in diagnosis, what is often missing from the conversation is the understanding that a diagnosis can also mean opening up oneself to face discrimination with employment, credit, or insurance.6 Because of the nature of power structures held in place by medical and social models, many people with disabilities fall prey and become captive to the care they receive, causing them to lose parts of their autonomy.

Disability is natural and part of a person’s whole identity, but it does not necessarily need to define a person—though in many instances it touches every aspect of our lives, and it can be a useful label or framework in this way. As disabled people, we should be allowed to be disabled and embody what that means, instead of it being a label or identity marker that “others” us. It is through experience, and an attitude of embodiment and reclamation, that barriers—and subsequently the hierarchy—have been broken down, and allow for disabilities and attitudes to grow along with the bodies of the people with them. In a letter she wrote to her imaginary 80-year-old self, not long before her death, Australian disability activist Stella Young describes what this reclamation meant for her:

“I stopped unconsciously apologizing for taking up space. […] I started changing my language. To jog your memory, back when you’re still thirty there are all kinds of fights about whether we are allowed to say ‘disabled people’ at all. It’s ‘people with disabilities’ that’s all the rage. […] But I’ve never had to say that I’m a person who is a woman, or a person who is Australian, or a person who knits. Somehow, we’re supposed to buy this notion that if we use the term disabled too much, it might strip us of our personhood. But that shame has become attached to the notion of disability, it’s not your shame. It took a while to learn that, so I hope you’ve never forgotten. I started calling myself a disabled woman, and a crip. A good thirteen years after seventeen-year-old me started saying crip, it still horrifies people. I do it because it’s a word that makes me feel strong and powerful. It is a word other activists have used before me, and I use it to honor them.”8

Young’s claim, and identity as “crip,” is to own the impairments, disabilities, and the differences that popular culture tells us are shameful; paralleling queer and feminist theories around identity construction. It makes way for a disruptive potential of disability and confronts the compulsory able-bodiedness of normative culture, unmasking the small-minded assumptions that create and sustain power, control, and exclusion.9 It seems paradoxical that the claim to individual experience then creates a collective identity, but the difference is judged against ableist norms, and identity is grounded in shared embodied social and political experiences and ideals.

Through my experience with limited mobility and being away from work I found comfort in the things that I could do, and returned to quilting as a primary practice. I found myself put at ease by the ability to control my experience and pain management, through an art that forced me to stand for small bouts of time and sit until my pain had subsided. It was through From Dust We Are Made, and Dust We Become that I explored the collective identity and relationship between myself and my ancestors. In the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the subsequential uprising in the name of BLM, I was longing to feel safe and to feel connected to my family and understand my position as a Black male artist in America. I needed to place myself and my work within the context of being Black and American. Having my friends—who have grown to be a part of my chosen family—leave to protest and to aid others reminded of Mary Patterson Leary, a Black educator and abolitionist for whom the Ohio Star quilt pattern was created. I created an intricate pattern using the Ohio Star motif to represent my family members and ancestors—a pattern that has become so ubiquitous with traditions of American quilting that it felt uncomfortable to use, with its common associations and the most famous of quilters being white women. I persisted through the piece, and found solace and reclamation in the use of the pattern.

Through this intentional practice of quilting I was able to connect with a community within myself. Similarly, through the research and writing of this essay and a close examination of my own hierarchy and journey with disability as an identity, I understand the importance of the freedom to choose and the freedom to define identity. The freedom to choose how to define oneself does not satisfy a goal of universal acceptance, but its explanatory capacity and contribution to making a society in which people with disability—and all vulnerable and marginalized people—have increased agency.