T(his) Story Has No End (Or, We Work All The Time)

Weisman curator Diane Mullin offers an in-depth consideration of the complex historical and philosophical underpinnings of Polish-born Piotr Szyhalski's provocative multimedia project "Labor Camp."

A LABOR CAMP IS A DETENTION FACILITY where inmates are held and forcibly engaged in penal toil. These facilities typically incarcerate political dissidents along with hardened criminals. Throughout history, particularly in the twentieth century, there have been many notable—and notorious—labor camps. Some of the most infamous of these include the Imperial Russian Siberian camps and their Soviet successor the Gulag; early 20th century Japanese camps where inmates worked on projects such as the Death Railway; Nazi Arbeitslager and some concentration camps that provided labor for the German war industry, urban infrastructure repair, and agricultural work; Communist Romanian camps where “enemies of the people” were “re-educated” through forced labor; and the wide variety of work camps established during the Chinese political and Cultural Revolutions under Chairman Mao. These historical circumstances and moments are so daunting to the collective imagination, that forced labor camps like these have indelibly marked our shared cultural memory of those places and eras. They have even had an effect on language, such as the metonymic use of the word Siberia—originally defined as a specific geo-political region and now a stand-in for the very idea of the brutal prison camp.

Polish-born, Twin Cities-based media artist Piotr Szyhalski has in the past decade established his own Labor Camp—a multimedia, multipart art project that includes interactive web components, original music, videos, texts, a blog, and online resource sites. In the summer of 2004, the artist published/posted the following declaration:

Labor Camp rejects the notion that cultural contribution is made only through material goods broadly defined as art. Direct and conclusive denotation of cultural worth of any artifact is in truth impossible. An artistic product may address an urgent need, convey messages of import, or provide an insight into an unspoken truth. But all these are fleeting concerns. They are important only now and only to some. Time erases. People forget. Things break down. However: The forms developed in the process of artistic production do acquire an assessable value, but only inasmuch as they are the evidence of labor undertaken to construct them. The Labor itself is the only unchanging criterion of cultural merit. Thus: Suspending all ideological banners, we work. Through the labor of our hearts, minds and hands we render useless the endless chatter of moral ambiguity. Labor Camp celebrates beauty and dignity of labor: We Work All The Time. Labor Camp promotes immateriality: It exists at no particular location, and has no fixed physical form. Labor Camp encourages all forms of individualism: No man is equal. Labor Camp belongs to no one, and belongs to all.

This “credo” touches upon key issues at play in Szyhalski’s complex project. Those include the artist’s idea of history, the place and role of art in that history, the idea(l) of the individual, and propositions about ownership, permanence, and participation. In this brief (and incomplete) consideration of Szyhalski’s Labor Camp, I am interested, specifically, in the artist’s idea of art as evidence of labor, the notion of participation and collaboration that permeates the work, and the ways in which the project makes proposals about engagement with and intervention in history(ies).

WE?

Labor Camp announces again and again, “We Are Working All the Time.” On the Labor Camp blog, nestled in the category of “Labor Camp Texts” along side descriptions of the Labor Camp Orchestra’s “Research By Means of Sound,” we see only one main “author” (or contributor), the small p., which we must assume is Szyhalski himself. There is post after post written in poetic form describing p.’s work: “I never thought it would be possible./But these days/We are working more than ever!(1/10/08), “ “Worked all day./ There is still a lot of work to be done though./ I am going to work late tonight. (3/27/07).”

On and on, backwards in time, the viewer can reach into the archives of the Labor Camp blog and find a plethora of posts describing the repeated action of work with no reference to its content. Though p. refers to himself on occasion as “I,” he frequently states that “we” are working. We—the readers, viewers, participants (forced? willing? complicit?)—are left to wonder, who is this “we”? Partners? Colleagues? Inmates? Victims? Us? And, just who is this seemingly innocuous p., really? Labor organizer? Revolutionary leader? Little dictator?

WORKING ALL THE TIME

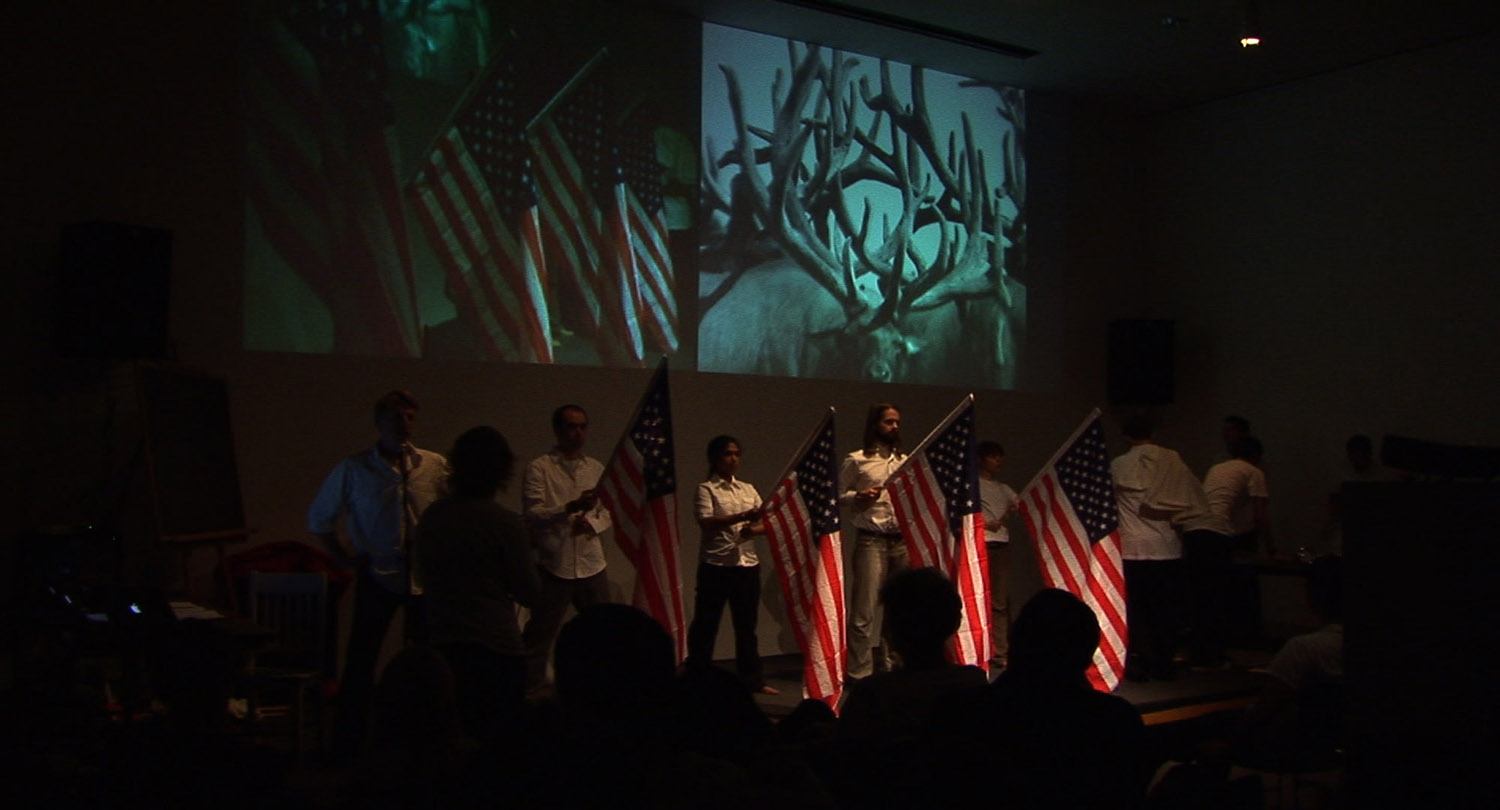

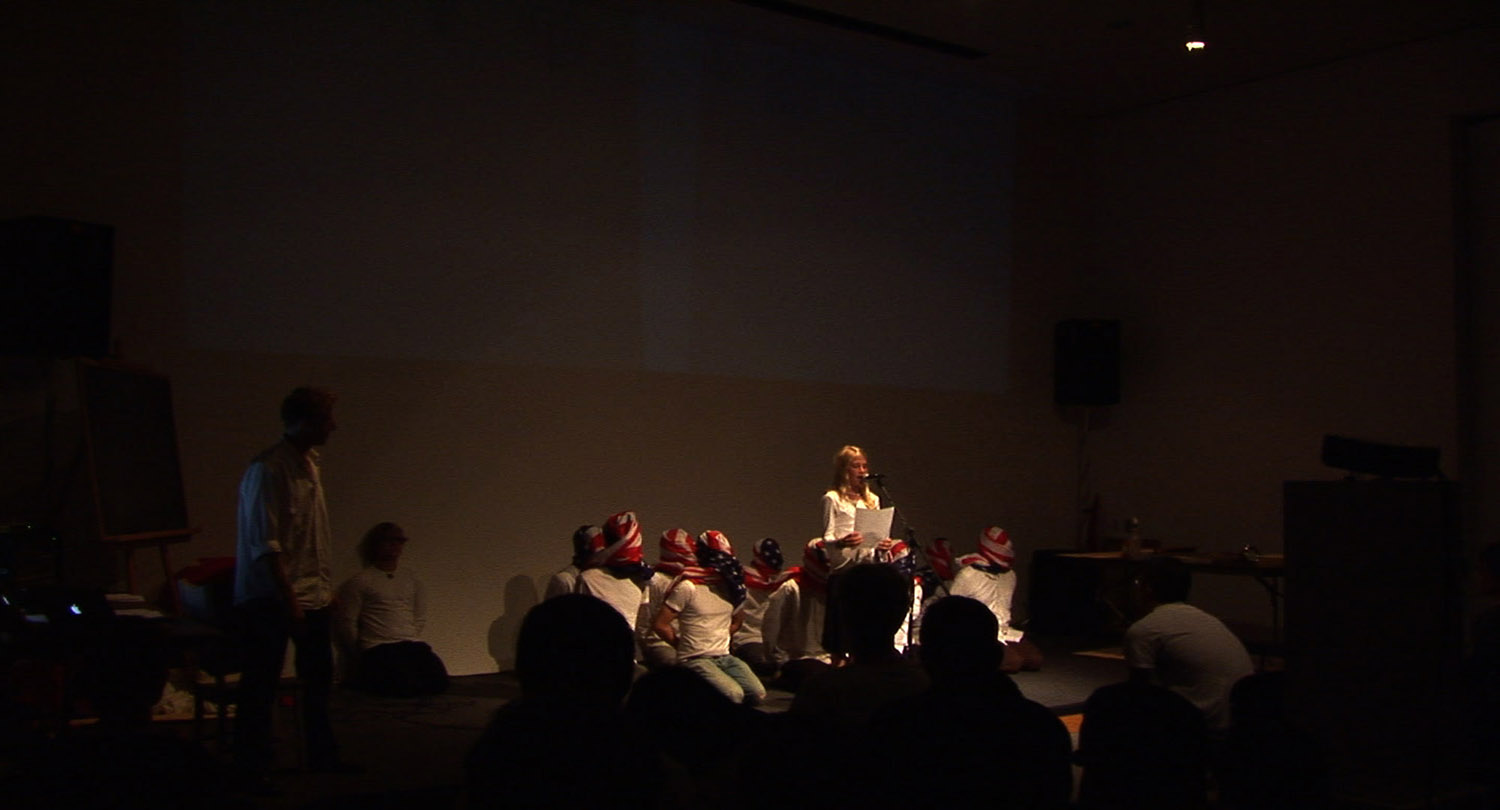

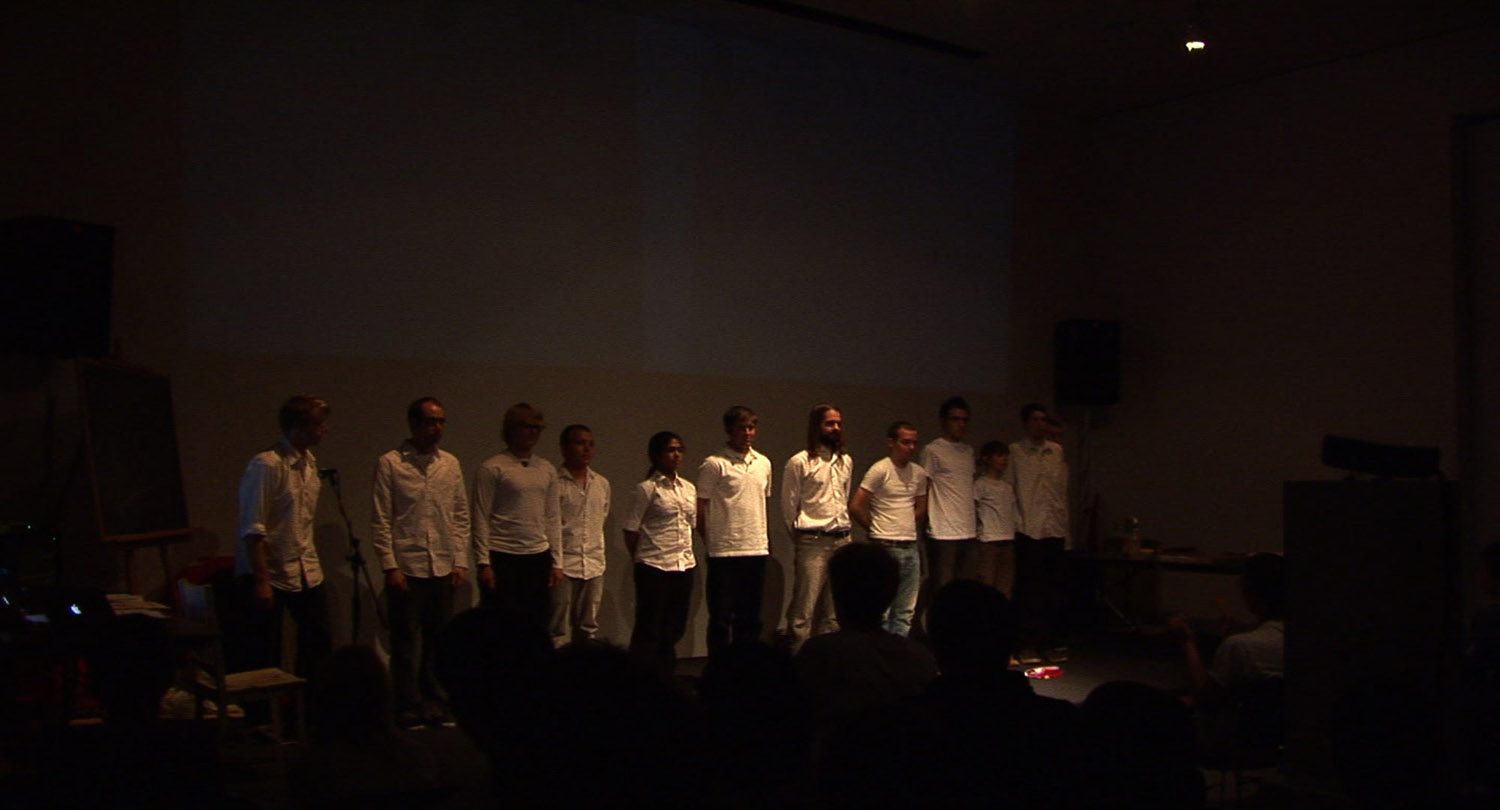

Throughout the dense sets of texts in the network that is Labor Camp, Szyhalski repeatedly asserts that “they” are working all the time. He also states in the Labor Camp credo, “The forms developed in the process of artistic production do acquire an assessable value, but only inasmuch as they are the evidence of labor undertaken to construct them. The Labor itself is the only unchanging criterion of cultural merit.” This interrogation of art as object—a means of exchange—posits that the only discernible value of art rests in its existence as labor. The artist underscores and dramatizes this sense of value as the process of work in live events like his recent artist talk/performance at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis in the fall of 2007. For that event, the artist brought along and engaged the members/inmates of Labor Camp. One group of these fellow campers spent the entire evening silk-screening posters declaring “We Are Working All the Time.” At the event’s end they were distributed free of charge to audience members, and in so doing, affirmed that the value is in the working, not the object.

Placing its focus on the work of the artist—and by extension of the human being—Labor Camp at once celebrates and completely rejects the ideology of historical revolutionary labor camps, especially those in operation during Mao’s regime. Szyhalski’s project recognizes the idea of re-education through forced labor as idealistic and despotic. What (and how!) good, Labor Camp begs, is such an education? When asked at the same public presentation at the Weisman Art Museum why he was working all the time, Szyhalski replied that he believes thinking, decision making, and living are all work. For him, the normative boundaries between work and play, work and thought, work and art-making are ultimately nonexistent. His answer to the question is at once straight forward and maddeningly oblique. His is not like the more common (and deeply nostalgic) association of the artist’s work with that of farmers, carpenters, and other people who “work with their hands;” likewise, his conception of creative endeavor isn’t like the more contemporary equation of the work of the artist with that of the intellectual. Szyhalski, instead, equates the artist’s work with that done in labor camps—penal servitude, rooted in either industry or need, or revolution and consciousness-altering ideology. In this way, he again confuses the issue—and us—making what we think we know something we don’t, and what we think we believe, somehow, less certain. In this, Labor Camp makes us all work, all the time.

T(HIS STORY) IS NOT ENDED

In 1939, cultural critic Walter Benjamin described history as an angel being blown backwards into the future. In his view, the angel of history is always and forever looking backwards trying to pick up and arrange the pieces of what has already happened. This conception of history has been deeply influential for postmodern thinkers, for whom this notion is expressive of the constructed (or artificial) nature of history itself; this postmodern view of history stands in contrast to the view of those modern thinkers (and artists) who imagine history as an inevitable progression of ever-more-enlightened ideas and actions leading to a supreme (and glorious) “end.” Like (or perhaps a part of) the postmodern critique of this view of history, Labor Camp suggests another model of time. This paradigm hinges on a simple phrase, used again and again in its documents: “all the time.” The phrase is at once a vague generalization of time and a powerful invocation of the constant import of time itself. Labor Camp evokes, surveys, and analyzes a number of models of time and, by extension, of history. Within Labor Camp time includes musical meter, global history, and personal history. Throughout the network of ideas in this project, we see these temporal forms as both distinct and intersecting, not blurred or glibly generalized as propaganda; rather, the project presents a more complex system that allows for both difference and relation. The artist’s own identity as a Pole marks many elements of Labor Camp, for instance. This assertion of the personal is complicated, but its navigation can help illuminate some of Labor Camp’s propositions about history and identity.

Imperial Russia’s Katorga system of Siberian prison camps was disproportionately peopled by Poles. The minority Polish population that was living in Siberia at that time (known as the Sybiraks) was originally brought there as punishment for involvement in nationalist uprisings opposing Russia’s intervention in the former state of Poland. There were many such uprisings in the years following the 1795 demise of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a liberal democratic multi-ethnic state that, in the midst of internal difficulties, was eventually partitioned by the neighboring Russian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia, and the Hapsburg Monarchy. The most important of those uprisings—those in 1830-31 and 1863-65—came to such bad ends that they altered the Polish national self-image. During that time, Positivist philosophers in Poland managed to forge a system of thought that dismissed these uprisings and related seditious activities as not possibly worthwhile. Poles, they said, should stop this yearning for things they cannot have and focus instead on useful productivity. This positivist view of Poland would eventually become the official state philosophy.

Never willing to settle for one side of the argument, Szyhalski has spent his career investigating propaganda: it’s the subject central to both his art and his extremely popular BFA class on the subject at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. In this media project, the artist makes an example of his own nation’s history to look more closely at the nuances underlying propaganda: were the Poles better off measuring their worth by their aspirations? Or, as the Positivists and their official state philosophy suggested, were they, in fact, better served by simply getting down to work? This specific national history certainly marks Szyhalski’s own identity and work, but it also serves as a metaphor for more broadly conceived consideration of history and ideology in the Labor Camp project. This relationship between the effects of personal and public history seems, in fact, to sit at the heart of Labor Camp, providing a tension that animates the entire work.

NO END/NO EQUAL

In 1776, Thomas Jefferson famously claimed in the U.S. Declaration of Independence that “All men are created equal.” This sentiment would be further codified in the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1789. The Polish-Lithuanians and French followed suit, ratifying similarly egalitarian-minded constitutions according to this important benchmark of modern federal law in 1791.Chairman Mao, likewise, used his own brand of idealized language to describe his vision of the new China. Along with political rhetoric, Mao also wrote poetry. Again, Labor Camp plays in the seeming contradiction. What is the difference between political rhetoric and poetry? Is it all that different or, maybe, the same? The Labor Camp credo states: “No Man is Equal” in clear reference and challenge to Jefferson’s words. What does Labor Camp Orchestra mean by its words, “no man is equal”? Is this a statement of defeat or hope? Perhaps Szyhalski is highlighting the fact that the concept of equality, so commonly taken for granted and dear to modern Americans, is in fact a hotly contested idea in both philosophy and political science. How might history have been different if Jefferson had penned “no man is equal”?

In the beginning of the Labor Camp Orchestra song “No End”, a young girl’s voice (it is Szyhalski’s ten-year-old daughter) marks time by a repeated, simple “pum pum” and then states matter-of-factly, “This story has not ended/It has not yet become history.” History here, as the child sees it, is not certain; it may yet have a good ending. Throughout the song, however, this voice also repeats the words, “no end” as another keeper of meter. By the end of the track the “no end” chorus dominates and the girl seems to have come to realize there may be no end—good or bad. Now we have a conundrum: is this good news or bad? What if there is no end? No end to despotism? No end to torture? No end to misguided idealism? In the manner of the entire project, the contradictory is offered as a possible way out. Could no end also mean no goal? No ideal toward which tyrants strive at all costs?

In this way, Labor Camp relentlessly mines the contradictory nature of the ideal—in art and political reality. The project, in fact, defies any neatly totalizing stance through this focus on the nature of the ideal. The Labor Camp Orchestra, we are told in its credo, “remains committed to the construction of auditory experiences, which follow no singular philosophy, process or idea.” What are we to make of this contradiction, however? In the end (or this end, for now) we are left with our own conundrum (work). As a practical “solution” Labor Camp seems to propose that we might at least consider the possibility that, in the end, the idea(l) of No End may be the best idea(l).

______________________________________________________

About the author: Diane Mullin is associate curator at The Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum and co-curator of the current exhibition Paul Shambroom: Picturing Power.